Original Publication: Vogue – December, 1987

Oliver Stone’s first words to me were that he had a gun and that he was planning to use it. “I can’t decide whether to kill Lew Wasserman at Universal or Michael Eisner at Paramount,” he whispered. It was a fairly effective opening line.

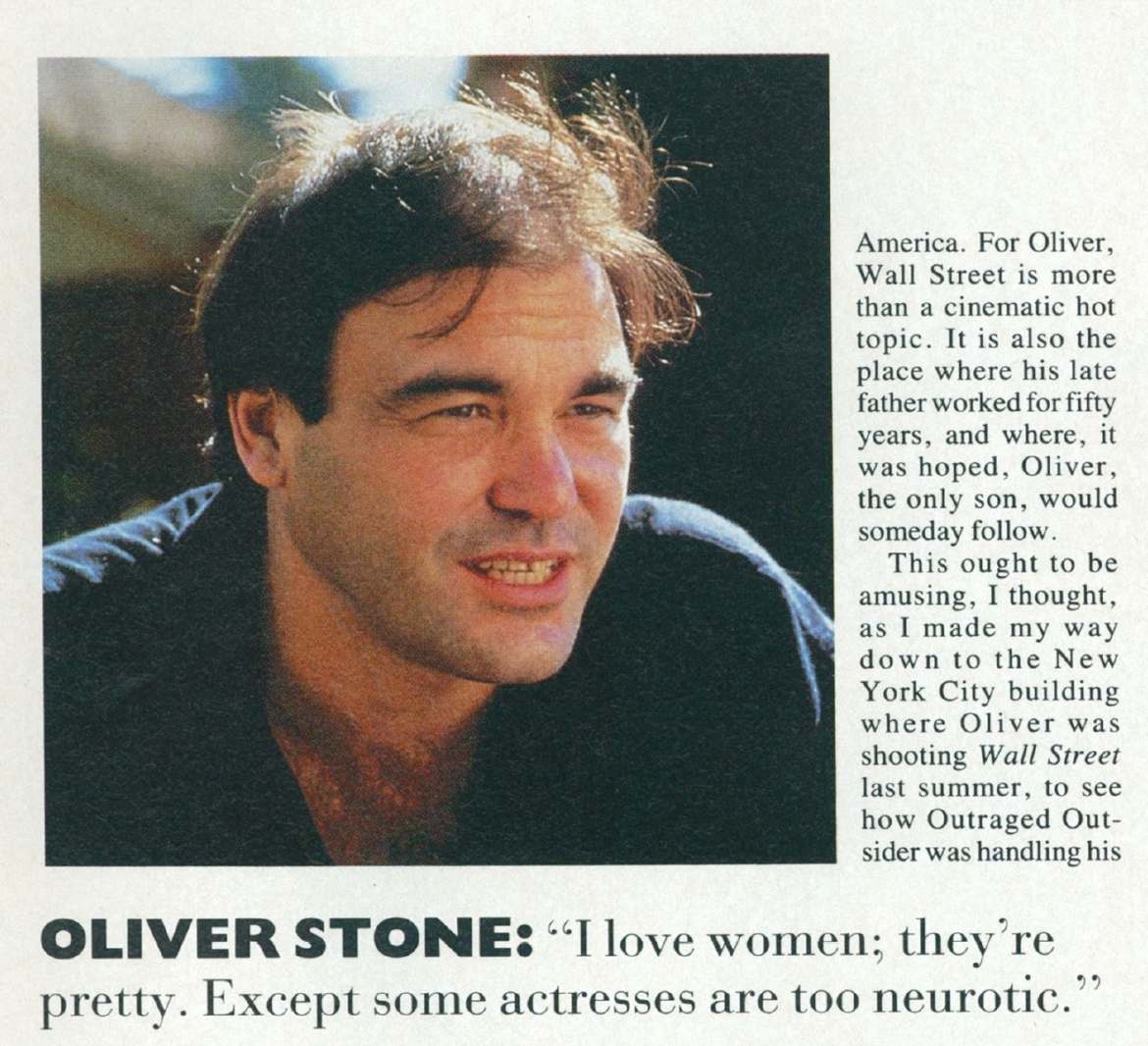

Today, nine years after that eruption of frustration over not being able to get Platoon made, “bad boy” Oliver Stone has gone from seething screenwriter to sweepstakes winner of the 1987 Academy Awards – for writing and directing Platoon. But even by 1985, when he directed the daring and gritty Salvador (for free, to prove he was a film maker), the moneyed set on the Bel Air screening circuit was beginning to have second opinions. And now, this month, Oliver Stone, the accomplished auteur, returns with Wall Street, an up-to-the-minute account of the not-so-pure financial heart of America. For Oliver, Wall Street is more than a cinematic hot topic. It is also the place where his late father worked for fifty years, and where, it was hoped, Oliver, the only son, would someday follow.

This ought to be amusing, I thought, as I made my way down to the New York City building where Oliver was shooting Wall Street last summer, to see how Outraged Outsider was handling his new identity as In Director. Wearing a black Vietcong-like jumpsuit, his wristwatch strapped around his belt, Oliver (ever the guerrilla warrior) stood in the middle of an authentically re-created trading room of a brokerage house, surrounded by dozens of young dressed-for-success extras. His attractive wife, Elizabeth, who functions unofficially as his manager, and his lively two-and-a-half-year-old son, Sean, were also visiting. “Fall boom!” Sean commanded me, making an imaginary gun with his fingers – the legacy, his mother said, of spending his first two years on the sets of Salvador and Platoon. Oliver, who can, depending on the moment, be charming or moody, seemed thrilled by his success, his anger replaced by a voracity for work. But in at least one respect he hadn’t changed at all.

“You’re not going to reveal what’s in this scene we’re shooting, are you?” he asked nervously. “Critics don’t like it if they read what happens before they see it.” For years Oliver had complained that prominent film critics never gave him a fair shake. Now that he’s their darling, he’s more worried. “Oh, Oliver, gimme a break,” I said. But right then we didn’t have a lot of time to talk.

It was time for Wall Street’s star, Charlie Sheen, to be led away in handcuffs in front of the whole trading room. Sheen was required to sob on cue and walk backward while wearing a specially rigged forty-pound camera on a harness, a bit of inventive cinematography to let us see his face in close-up and a lot of background emotion too. Sheen was bringing himself to tears by reading and rereading what appeared to be a four-page handwritten letter from his father, Martin Sheen. “I think I love Charlie,” Oliver said. “I feel like he’s me at twenty-one; he’s always been in trouble.”

Wall Street, like Platoon, is both a morality play and a youthful rite of passage. Against a backdrop of New York’s sleekest skyscrapers, poshest watering holes, and fanciest Hamptons beach houses (so we can watch Daryl Hannah – playing an ambitious interior decorator – come out of the water), the movie deals with the seduction, corruption, and redemption of one young stockbroker. It also attempts to explain why Wall Street today is the home of yuppie greed, chi-chi high-stakes arbitrage, and insider trading. But for the first time in any of Oliver’s films, there is no blood-and-guts violence. “It’s all verbal violence,” he said. “I wanted to do something about people who are literate and intelligent.”

“Will we understand why a Dennis Levine is today behind bars?” I ask Oliver a few days after shooting was completed.

“The movie deals with a relativity of wealth,” Oliver explains. “There is a scene early on when Michael Douglas [playing a criminal Ivan Boesky-like character who seduces Sheen into crime] says to the kid, ‘No one can make you really, really rich. I’m not talking about $400,000 a year, some working Wall Street stiff. I’m talking really, really rich — $100 to $300 million.’ That’s the way the new Wall Street’s been thinking . . . . The volume’s jumped enormously. With that has come the whole inflation of corporate debt, and the movie indirectly explains why that debt leads to hypocrisy, to lying, to greed.”

A stickler for realism, Oliver consulted some of the street’s best-known names – Ichan, Pickens, and Gutfreund – and had a least one authentic Wall Street type (like investment banker Ken Lipper, with whom he’s written a novelization of the movie) on the set at all times. All 240 Quotron screens on the set that show stock quotations were programmed to reflect the script’s dialogue, and, in a first for a commercial film, Oliver was able to shoot on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Oliver got the idea for Wall Street when a friend who worked as a commodities trader, and who had become a millionaire in his early thirties, took a tremendous reversal. “His life style was shocking to me – two houses in Bridgehampton, Porsches, Mercedeses, dune buggies,” says Oliver.

But the longer Oliver talks the more it sounds as if the then larger, more soulful debt is owed to his father, Louis Stone, a retail stockbroker and conservative Goldwater Republican. (Oliver briefly appears in the movie, placing an order to “Lou.”) For a long while, the father-and-son relationship was a stormy one. “I was pretty much of a disappointment to my father for thirty years,” Oliver says. “When I told him I wanted to write, he thought I was crazy because he thought I was a terrible writer. And then when I said ‘movies,’ he thought I’d committee double jeopardy. He turned around a little after I won the Oscar for the screenplay of Midnight Express; before he died he said, ‘Maybe you made the right decision because there is a future in this home-entertainment stuff.’”

Oliver’s mother is French, Catholic, a colorful Regine-like character whom he describes as “such an exotic bird.” She separated from his father, an introverted and atheistic Jew, when Oliver was fourteen. Oliver says his adolescence was Catcher in the Rye; his time in Vietnam painful; his marriage to a sophisticated, older Iranian woman not so easy either; and his years at New York University’s film school mostly catatonic. But even during the height of the dames-and-drugs period following his divorce, Oliver always stayed with his father when he came to New York City and spoke of him with affection and respect.

“I’m trying to live according to the dictates that my father left me,” Oliver says now. “One thing he always used to say is on the front of Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue: ‘Love justice, Do mercy, Walk humbly with thy God.’ I feel my father would be prouder of me if I take the chance, if I say something political.”

And how does that square with his feelings about Wall Street?

“I’m split on Wall Street. It has a good side – providing capital for America, for research, for science, for building housing projects and municipal bonds. There’s a good aspect to the raiders, too: they’re buccaneers, rebels, antiestablishment. The bad side is the buying and selling of companies – not to improve the company, not to create anything, just to make money.”

Yet for all his being such a moral sage these days, I remind Oliver that he still hasn’t written a decent female part.

“I love to be around women: they’re very pretty. Except some of the actresses are too neurotic; some of them are driving me nuts. But I’ve had good experiences with Daryl and Elpedia Carrillo [in Salvador], and if I start to write about more domestic things, more women will come into play. I’ve been writing about ideas of maleness, but I might surprise you.”

“What about violence and rage?” I want to know. “Is there still a lot of rage inside of you?”

“You be the judge. What do you think?”

“Considering the first time we met? When you told me you had a gun and couldn’t decide which Hollywood mogul to kill?”

Then Oliver laughs and laughs. “I still have a gun,” he says.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments