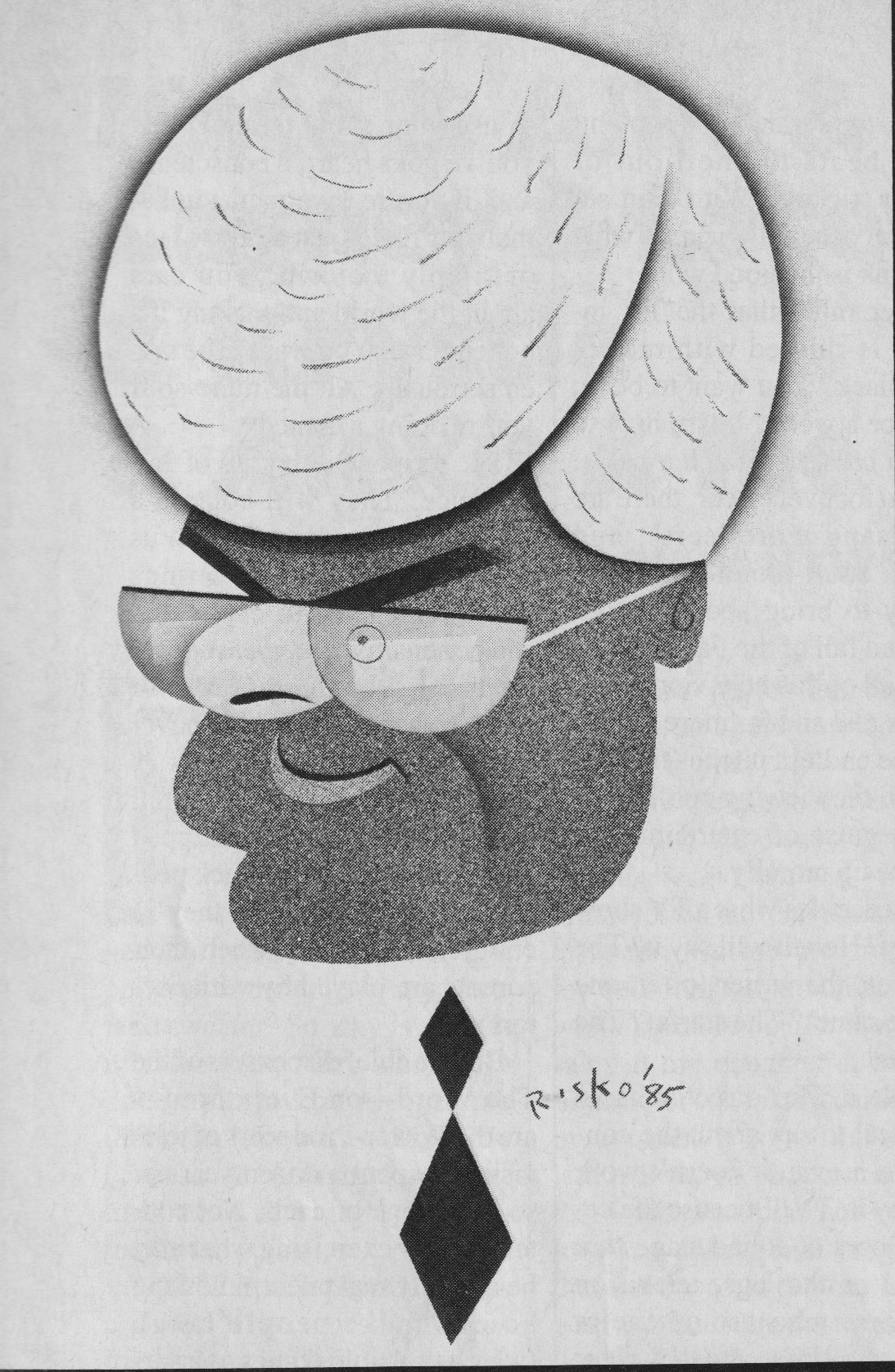

Original Publication: Vogue – February, 1985

Phil Donahue works the air waves like a revival meeting. Incest, wife-beating, transexuality, and rape – Donahue has encouraged America to spill its darkest secrets. What’s next for the heavenly host who’s one step ahead of the news?

Phil Donahue has just completed one of the trickiest triple plays in TV history. After a humble start as a local talk-show host in Dayton, Ohio, in 1967, Donahue moved to the big city – Chicago – in 1974. Now America’s number-one syndicated talk show seen in 214 cities, Donahue has moved to New York City with its original Dayton crew still intact.

Phil Donahue’s success is all the more striking because he has gone to the top by defying the men who program daytime television: he banked on the intelligence of women. “We were born in Dayton,” Donahue explains. “We didn’t have any stars to call on, so we were forced to discuss issues.”

Donahue’s show is predicated on the idea that women who make up 85 percent of his audience will ask his guests questions at least as interesting as his own. The show has become an armchair forum of pop culture and a popularizer of serious issues: Boy George or Raquel Welch is on one day, a discussion of a nuclear holocaust or the flat-rate tax the next day.

Central to the show’s appeal, of course, is Donahue himself, a forty-nine-year-old former altar boy from Cleveland. A graduate of Notre Dame, he married young and became the father of five children in six years. As his career blossomed he fell away from his Catholic faith, then from the mother of his children. Neither was shed lightly, and today Donahue spends much of his professional life asking questions to which he was once certain he had absolute answers. Now his certainty is gone. That loss appears to be the key to his intesnsity and the motivation for his constant probing of just why we behave the way we do. In fact, Donahue is planning to break into prime time this fall with five one-hour specials and an accompanying book on the subject, all tentatively titled “The Human Animal.” Humans are clearly his favorite animals, “What does the recognition of our own mortality mean in terms of our behavior?” he asks. “What is the arousal mechanism of the male, and why is it so easily triggered; and why are men responsible for most violent crimes?”

As he ticks off these questions, Donahue jumps up from the couch in his comfortable apartment, uncovering a green-and-white needlepoint pillow that reads, “You can always tell an Irishman but you can’t tell him much.” The pillow was a wedding gift from a friend of his current wife, activist-actress Marlo Thomas, whom he married in 1980.

Like many professional interviewers, however, Phil Donahue does not enjoy being interviewed himself.

Maureen Orth: You have described yourself as the “world’s oldest altar boy” and yet others tell me you’re shameless. For example, you’ll scratch your head and say, “Oh gee whiz, Raquel Welch, those mammary glands . . . how was it growing up with those?”

Phil Donahue: It’s pretty silly to avoid that issue with someone like Raquel Welch in a culture that sells everything with boobs. I don’t plan surprise attacks. I try to make life as comfortable as possible for the guest. If I don’t brief my guests, most of them will be ambushed by the audience. But I also have a responsibility to the audience – they’ve waited two years for their tickets. I may get myself to a place where I think, well, maybe we’re not getting at any issues about which people really care. That may have triggered my question about her breasts. Pace is important. It doesn’t have to be a circus, but you can’t sit back and be professorial – it just won’t work.

MO: It seems your show is often ahead of the network news in what it explores. Do you ever feel you’re given short shrift in the profession?

PD: No, but I do think there is prejudice about daytime television. That’s evidenced by the fact we have no imitators. We discovered there is an audience that wanted the kind of show we do. But we cannot claim to be network news correspondents. They don’t have the elbow room I have to be semi-witty while I work. Also I have an audience, and Phil is running around with this microphone. I think that’s provoked questions about what I am – am I press or entertainer?

MO: When you run down that aisle with the microphone, how do you maintain control?

PD: A lot goes on you don’t see. I try to make clear to the audience not to worry about asking something stupid, and during the breaks I’m all over the place making house calls, so to speak, to convey a sense of family withing the studio itself. Part of my instruction to the guest is, “Don’t turn off during commercial breaks. If you do the energy will drain out of the room.” By the time the program is over I have worked over sixty minutes to make the occasion one in which the audicence is most likely to stand up and participate.

MO: How do you decide on a topic you think is going to grab people?

PD: We have six very creative women in the office who make most of the decisions about what you see. You can’t write a pamphlet: “This is what makes a good show.” We don’t hit it over the fence every day, but we almost never die because after four thousand shows we’ve made all the mistakes. When we die, we die big. Johnny Carson can cue the band. I don’t have a band. The result is we bring a greater anxiety to the decision of whom we have on the program.

MO: Have the issues changed over the years?

PD: I think there’s an increased awareness of the value of the political positions that feminists have been offering. This has been triggered by the staggering number of women who have gone out of the home to work. These women at first had some misgivings about feminists, wondered if they liked men, etc. A lot of that had to do with the way the white male media were covering feminism. They looked for opportunities to trivialize the movement. There was no reliable way to disseminate what feminists were saying: for example, that kids get too much mother and not enough father. When they said that, they certainly made me feel self-conscious.

MO: What are your favorite kinds of issues?

PD: Issues about what makes us tick are particular favorites of mine. Why do we behave as we do? Why do we have so much aberrant behavior? How much humiliation and pain is being inflicted on children by people who bring doctrinaire religious fundamentalists convictions to parenthood? People who are too busy to watch a child because they have to work? How much has the feminist ideal of shared parenthood really found its way into Central Park here on a weekend?

MO: Has it?

PD: Yes. When I was married in 1959, I was twenty-two years old and my wife expected to stay home with the children, and almost no one is doing that today. My daughter at age nineteen is certainly much less interested in marriage than her mother was a nineteen. She’s going to expect to enter a corporation at a level commensurate with her abilities. She’s not going to make the coffee. These are tremendous changes.

MO: Your audience is the heartland. In New York City, there are a lot of loud-mouthed, media-savvy people. How are you going to adapt yourself to people who just want to use air time?

PD: New Yorkers have a sterotyped notion of who the people are in the Midwest, and curiously they have a sterotyped notion of who they are themselves. Men and women in Cleveland are worrying about the same things as men and women in New York. But everybody figures that people who pariticpate in the Donahue show here will all talk like Jimmy Breslin and be pushy. If they do, I’ll welcome it – it’s a sign that the person cares.

MO: But you yourself don’t like to be interviewed, do you?

PD: I’m a little nervous about it. I know what it’s like to die as an interviewer, and I don’t want to disappoint. And, well, I’m not in charge of it.

MO: Is the reason you’re coming to New York mainly personal – so that you and your wife, Marlo Thomas, won’t have a commuting marriage?

PD: Yes. It’s personal. It gets us off airplanes and I get to come home every night. We also get the creative juices flowing again – you get freshmanitis. You know: What if they don’t like us? There’s all this anxiety, and it’s good for us.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments