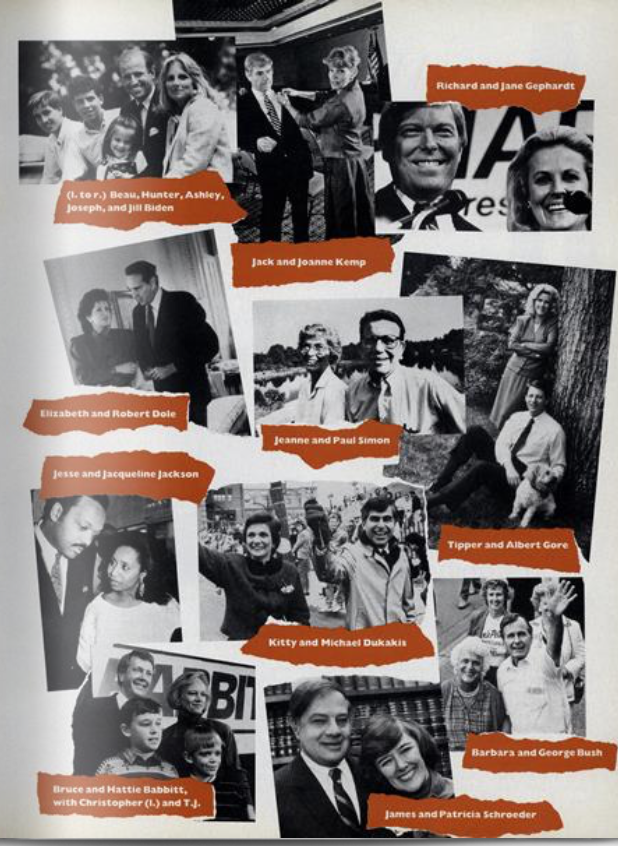

Original Publication — Vogue, November, 1987

Today’s political spouse must be so independent, diplomatic, indefatigable, not to mention loyal, it’s a wonder we haven’t elected a Mrs. President. When we do, her husband ought to be one helluva guy.

This year, on the campaign trail, the political wife is behaving—and the press is covering her—almost as if she herself were the candidate.

Her role is complex, contradictory: she is required to be savvy, independent, committed to her own issues, strong enough to face relentless media scrutiny, but first and foremost, a loyal wife and mother. A living paradox, she reflects the profound changes women have undergone during the last two decades—and the American people’s deep ambivalence about those changes. Today, Jackie Kennedy’s beauty and her glittering White House dinners wouldn’t be enough to carry her as First Lady; nor would Pat Nixon’s stoic silence. “Things have changed dramatically,” says Roger Stone, a Republican political consultant and advisor to candidate Jack Kemp, GOP Congressman of New York. “Now wives are seen as full partners.”

The tradition of activist First Ladies—some controversial—is a long one: from Edith Wilson and Eleanor Roosevelt to Rosalynn Carter and Nancy Reagan. Twenty years ago, Lady Bird Johnson logged thousands of miles on her own with her highway beautification project. But today, even before her husband is elected, the political wife has essential work to do in the early primary states, and usually little say about her own schedule. This is especially true during Campaign ’88, when there are more than a dozen candidates overall.

For the wife who frequently stands in for her candidate husband (a notable exception is Jacqueline Jackson), the primaries are grueling work demanding cheery smiles, endless patience, and up-to-the-minute knowledge on issues. She must follow an extremely tight schedule, going from one tiny backwater town to another with a ready speech, but no guarantee that anyone will show up. Often separated from her family, her career on hold, she frequently has to bargain with recalcitrant aides to arrange a joint appearance with her husband in order to see him at all. Few of these wives can recall the last time they had dinner alone with their husbands.

Jill Biden, thirty-six, a teacher who is married to the former Democratic hopeful, Senator Joseph Biden of Delaware, is not a veteran campaigner. She married her husband ten years ago, after his first wife and infant daughter were killed in a car crash, leaving him with two small boys to raise. It is the end of last summer, and Jill Biden is standing on the front porch of a famer’s house in Muscatine, Iowa. She has just given a speech to exactly ten people, assuring them that her husband would establish a day-care center in the White House. She borrows the famer’s living-room couch for a chance to sit down. “Sometimes, after I fly back to Washington, I just wish I could go straight from the airport to a motel and sleep for an hour before going home,” she says—home to food shopping, to overseeing the details of her children’s lives, to teaching emotionally disturbed teenagers five days a week, and to the prospect of flying in and out of New Hampshire every Wednesday night before the primary. “Sometimes I say to my six-year-old daughter, ‘Just let Mommy lie down for twenty minutes, then I can talk to you.’”

Like many of the candidates’ wives, Jeanne Simon, sixty-five, lawyer, wife of Democratic Senator Paul Simon of Illinois, and mother of two, has her own press secretary and her own scheduling person, and refers to herself as her husband’s “number-one surrogate.”

“What I do is just the same thing Paul does. I meet with people, talk to the press, do radio interviews and television programs. I’m talking for Paul. That’s my job. I think I know him better than anyone else. I understand how he thinks and how he feels, and I think I can interpret it rather well.”

But not too well, some political advisers hope, because the cardinal rule in spousal politics (most recently illustrated by Elizabeth Dole) is that there can only be one star in the family. Jeanne Simon has abided by this rule: “I feel one elected official in the family is certainly enough,” she says. In choosing to serve as the public extension of her husband, she has sacrificed her own career. Jeanne Simon was voted to the Illinois State Legislature in 1956. She gave up seeking elective office when she married, then quit her job as an assistant attorney general in Illinois in 1984 when her husband ran for the Senate. Recently, she reportedly bypassed a chance to run for lieutenant governor of Illinois. (If her husband is elected President, Jeanne Simon says she plans to lobby on Capitol Hill for bills she feels strongly about.)

The public may also see a wife who is “too” effective on the stump as a minus rather than a plus. Says a young man who recently heard a speech by Hattie Babbitt, the accomplished lawyer and mother of two who is married to Democratic candidate ex-governor of Arizona Bruce Babbitt, “Hattie Babbitt’s so good, she makes you think maybe she wants to be the candidate.” Adds Betty McMahon, Iowa’s Muscatine County Democratic Chair, “We don’t want anyone running the President the way we got now.”

That veiled reference to Nancy Reagan is not without irony, considering the rocky road the First Lady has traversed. At the beginning of her husband’s first term, she was denounced for having lavish tastes and no real interests beyond designer clothes and lunching with Betsy Bloomingdale. Today, any First Lady must be vitally involved in a serious issue—and the right sort of issue. For Nancy Reagan, that issue has become drug abuse and the “Just Say No” campaign. Barbara Bush, wife of the Republican front-runner, works hard on literacy. Kitty Dukakis, married to Democratic aspirant Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, co-chaired her husband’s committee on the homeless, and Joanne Kemp has taken on Soviet Jewry. Obviously, no political wife is about to adopt anything so controversial as contra aid or abortion rights. But striking the right note can be tricky. At one point, Hattie Babbitt declared her issue as First Lady would be AIDS, but that didn’t fly well with audiences, so now she deemphasizes the topic.

And take the case of Tipper Gore, thirty-nine, and mother of four. Her husband, Presidential hopeful Democratic Senator Albert Gore of Tennessee, has made arms control his field of expertise; she has chosen a much more controversial cause. As cofounder of the Parents’ Music Resource Center, she has appeared before Congress and done battle in the media with rock personality Frank Zappa in her campaign to get the entertainment industry to police itself and label records that have violent or sexually explicit lyrics. She is also the author of the recently published book, Raising PG Kids in An X-Rated Society(Abingdon Press).

Although Tipper Gore calls herself a “liberal Democrat,” and counts as supporters the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National PTA, hers is an issue that has turned many liberals off. In a national syndicated newspaper column earlier this year, her husband’s last opponent in Tennessee even implied her campaign was partly a ruse to curry right-wing support in the South. “That made me furious,” she says. “I am the victim of these knee-jerk reactions from other liberals and more moderate people, who, instead of listening to what I’m saying and taking a look at the issues, make the mistake of thinking I am what I’m not, a right-wing fundamentalist conservative. That’s just absolutely ridiculous.” The question now becomes whether her prominence has helped or hurt her husband.

“The wife of a politician is basically forced to have interests—that’s the definition of a modern woman,” says William Schneider, a resident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC. “But if she steps beyond a certain point, she’s slapped down.”

Certainly Rosalynn Carter was criticized for sitting in on Jimmy Carter’s cabinet meetings, and Nancy Reagan is still feeling the sting from so publicly involving herself in the ouster of former White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan. But it is a measure of some progress that today not even Nancy Reagan would try to get away with campaigning as she did in 1980, leading the public to believe that her chief contribution was her adoring gaze at “Ronnie.”

Spouses today live under the greatly intensified media scrutiny, and consequently are at far greater risk that any blunder on their parts may damage the campaign. “Communications are so much more advanced,” says Barbara Bush. “If something happens today, it’s news today. It used to take two weeks for a faux pas to get out, and by then it was gone.”

Kitty Dukakis, fifty, who hopes to become the first Jewish First Lady, has been campaigning for her Greek-American husband on the state level for twenty-six years, but early on, she learned firsthand how unsettling it is to live in the glare of a Presidential campaign. A former teacher of modern dance, Kitty Dukakis works two days a week at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government developing models to improve and maintain public open spaces, and spends most of the rest of the time alone on the campaign trail. Late last summer, on her ninth trip to Iowa in three and one-half months, she drove an hour to an Indian settlement north of Marshalltown, only to hear the chief spin out a scheme to manufacture microchips on the reservation. (Later, he told this reporter that he headed a “patrilineal tribe,” and he didn’t think wives were important.) Kitty Dukakis was especially eager to meet privately with the settlement’s alcoholism counselors because she herself had revealed—after her husband announced for the Presidency—that she had been addicted to small amounts of amphetamines for twenty-six years without her husband’s knowledge (a habit she received treatment for and kicked in 1982).

Now Kitty Dukakis’ addiction has become one of her issues. “It was a very sad, very lonely time,” she says. “Now that I’m traveling around the country, I’m beginning to realize how I can help people—women, particularly—who have the same dependency I had.”

Considered smart but domineering in Massachusetts political circles, Kitty Dukakis more than once has interrupted her husband in a high-level meeting, handed him his coat, and told him it was time to go. The joke in Massachusetts is that Michael Dukakis would have an affair—if Kitty told him to. She has already suffered headlines for allegedly berating an airline pilot who kept her grounded on the runway for four hours. As a result, the press watches her very carefully—always on the lookout for other “mistakes” that could quickly unravel her husband’s entire Presidential effort. Now, when a reporter takes an interview with her, Dukakis has her own tape running.

Geraldine Ferraro certainly paid a painful price for trying to conceal her husband’s finances in 1984, and anyone contemplating a run for the Presidency today realizes there are no longer any family secrets—everything is fair game. Barbara Bush, however, calls “just plain ugly” questions like “Have you ever committed adultery?” Says Kitty Dukakis, “If I’m uncomfortable some day with a question I’m asked by the press, I will not answer that question, and that is my prerogative.” But Jeanne Simon welcomes them all: “For the most important job in the Free World, we ought to be able to take a little scrutiny.”

Since Gary Hart’s flouting of traditional family values, and revelations of dalliances by Presidents like Kennedy and Johnson, a political wife today is supposed to be the living proof of her husband’s credibility as a family man and his rectitude on the crucial “character issue,” an issue apparently of particular importance to women. When the news broke of Gary Hart’s involvement with model Donna Rice, a New York Times/CBS News poll showed a nine-point gender gap, with fewer women favorable toward him than men. In a close race, this kind of number simply cannot be ignored.

Needless to say, it would be political death for any of these women to disagree with her spouse in public. Few wives will even admit to any disagreements on issues in private, or of any lingering doubts about giving up their own careers. “I have been almost as involved in issues as Jack has,” says Joanne Kemp. “Of course, he has had the luxury of having that be his career. But there are so many fun, interesting, and challenging idea-oriented things to do with your life when you’re in this, it doesn’t make sense to look at the half-empty glass.” Tipper Gore gave up on the idea of becoming a child psychologist eleven years ago when her husband first decided to run for Congress. “I’ve espoused feminist ideology in certain respects,” she says. “But as I’ve grown older and had more experience, I can see that the role of self-sacrifice has fallen more heavily on the woman—not just in relation to a man, but because of children. Of course, I suppose because I am happy with my husband and our marriage I am willing to look at the brighter side of things.”

But Elizabeth Dole, who has no children, told this reporter in September she would draw the line at giving up her post as Secretary of Transportation if the presidential campaign of her husband, Senate Republican Minority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas, demanded it. “If the candidates—George Bush or Jack Kemp or Bob Dole—don’t have to give up their jobs, why should the spouse?” she said.

Three years ago, before her husband began to run seriously, when a favorite Washington game was “Which Dole will be the candidate?”, Elizabeth Dole sough the limelight frequently. Then, as her husband stepped forward as Presidential contender, she assumed a different role, that of political wife.

North Carolina-born Liddy Dole is the best known of all the candidates’ wives, the Republicans’ shining female star, and such an asset on campaign swings—especially with women in the South—that her husband once jokingly referred to her as his “Southern strategy.” To help him, it was reported she even journeyed to the television news archive at Vanderbilt University to study how he was edited on TV. She traveled often through the early primary states—according to The Washington Post, twenty-one days in a one-month period late last summer—often under the guise of the Department of Transportation business, though separate government and campaign tabs were kept.

This wifely work at a time when there were a major air crash and several near-misses made her the target of criticism in an Evans and Novak column last September. A front-page story the next day in The Washington Post, echoing that criticism, predicted that she would resign in November when her husband officially announced.

She resigned on September 14.

The unstated message is clear: Elizabeth Dole couldn’t have it all. The Republicans could not afford to have their candidate’s wife be responsible for air safety if there was the chance the Democrats might make that a major issue against them in the 1988 campaign. If Bob Dole wanted to be the nominee, and Elizabeth Dole wanted her husband to be President she had to give up her job.

One may ask if it’s fair to demand so much of the spouse—on one hand, to expect her to be committed and independent, but on the other, never to do anything that can be construed as “betraying” her man. “It creates a difficult dilemma,” says William Schneider. “We demand more commitment on the part of the candidate’s wife and demand that she be part of the team. Yet suppose she does differ? Is it essential a marriage be based on totally political compatibility? It is unfair. But what’s new is that now the political wife has become a member of the Administration.”

The idea has reportedly been floated at a spouse meeting of the National Governors’ Association that the wife of a governor be paid for the work she does on her husband’s behalf. This may be one way to begin to acknowledge the real contributions and the power of the political wife. Perhaps the time has come for the First Lady to start talking salary?

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.