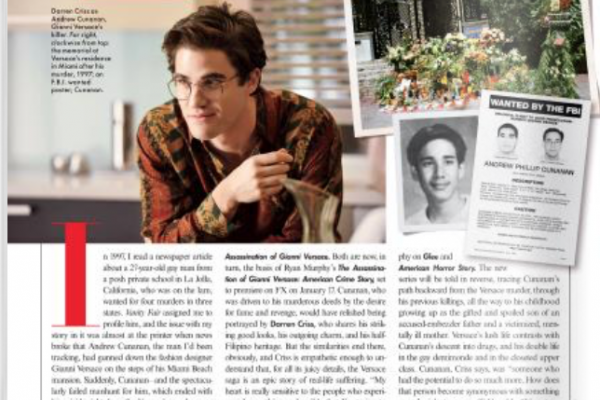

Original Publication: New York Woman – March, 1988.

“Money questions will be treated by cultured people in the same manner as sexual matters, with the same inconsistency, prudishness and hypocrisy.” – Sigmund Freud (1913)

Judy’s marriage almost broke up after her second child was born a year ago. She was working full time as a publicist for a record company and getting up as many as six times a night to nurse her newborn. Her husband who earned 40 percent more than she did, refused to help, insisting his sleep was more valuable. “I put a roof over our heads,” he said. The couple maintained separate checking accounts – she paid childcare, he paid the mortgage. Finally, in desperation, she decided to go into business for herself, working from home so she could get some sleep and save her marriage — in that order.

Judy was able to attract clients and immediately began to earn more than her husband. The money not only gave her independence but confidence – it seemed to be the only thing that forced him to deal with her equitably. Her husband now admits he was jealous of what he called her obsessive attention to the children and that he used money issues to punish her. “I felt I was bringing home the check and that entitled me to rule the roost. We are now a one-checkbook family. Getting a joint account was much more of a commitment to me than a marriage license.”

In a marriage, money is both cloak and dagger, a mask for countless infirmities and the ultimate weapon of power. Under the old contract the provisions were clear: the husband furnished financial support to his wife in exchange for physical and emotional sustenance. Now, however, two career couples (defined as “two husbands and no wife”) abound. For these couples especially, issues of money and control can be fraught with psychic travail. Dr. Ann Ruth Turkel, supervisor of psychotherapy at the William Alanson White Institute of Psychoanalysis, elaborates: “Money issues may symbolize internal conflicts over dependency, responsibility, exploitation and pride.”

Indeed they can. Three years ago, when I stopped working full time because I chose to have a baby, I felt guilty because I was no longer making the same monetary contribution to my marriage. I thought I was backing down from every notion of independence and equality I had ever espoused. “You better learn early,” said a woman married twenty-five years, “money is power in marriage.” I began to wonder about how other couples divvy up the dough, what their fiscal policies are and whether they practice what they preach.

First, to answer the most obvious question: yes, there are far fewer conflicts when there is plenty of income. “The reason we don’t fight about it is only because we make enough not to fight,” says a fast-track litigator who earns twice as much as her prominent journalist husband.

Yet even among New York’s elite corps of superwomen who can match or outearn their husbands’ six figure incomes, curiosities abound – specifically that the ability of a woman to earn a lot of money does not necessarily demystify the notion that the man is the family “provider.” In fact, dependency seems so ingrained in the women’s psyches that the most high-powered female executive will allow her husband to control the essentials because taking charge herself is somehow unfeminine. How the money is used, then, defines the roles played in marriage.

A senior vice president of a money management firm, married twenty-three years to his investment banker wife, explains they maintain separate checking accounts and separate investments – “She has profit sharing and equity funds, I have a fixed income” — but that it is his income that runs the family. “I have always paid for the mortgages, the utilities, the car and our two children’s schools. She handles the kids’ clothing, the food, the decorating, and pays for the renovation of the house. She has more fun with her income.”

Certain younger career women see maintaining separate accounts and dividing each expense down to the penny as a badge of their equality. They wouldn’t dream of allowing their income to be thought of as discretionary, but they, too, can contradict themselves.

Rhonda is an attorney in her early thirties, married almost two years to Rory, a garment industry salesman. She earns slightly more than he does. Rhonda is so adamant about all expenses being equally divided that they pay for their co-op with two separate checks from their separate accounts. Neither has a say in the other’s investments. There is no food budget because they eat out almost every night. But guess who pays for dinner? Rory. “It’s like a date,” Rhonda explains. “It is unfair, but he hasn’t protested yet.”

At least Rhonda takes an active interest in what happens to her paycheck. Some women who are competent and secure opt out of the process totally. Take Brenda, the head of a successful company she founded two year ago, just about the time her husband of fifteen years suddenly announced their marriage was over. What Brenda learned then was that although she had worked throughout the marriage, earning as much and sometimes more than her husband, they had no insurance, no savings. She had let him handle everything and he did – badly. So at the height of her career she had to take in a boarder to help pay the rent. Today Brenda says, “Abdicating control of your money is abdicating control of your life.” Unfortunately, not everybody figures that one out. Mary B. Lehman, senior vice president for business development and financial planning at United States Trust says, “Even after we work with women, they usually leave the big decisions on how to invest their joint incomes to their husbands.”

Some women have trouble taking on any fiscal role at all. Carol is a fundraiser who inherited money from her mother and married an older man who was divorced with three children. They then proceeded to have three of their own. A big chunk of her husband’s income goes to alimony and supporting his first family, and he can’t understand why Carol doesn’t make more of an effort to help him. At his urging she got a money manager and started making more money on her trust than her brothers. But earning more than the men in her family made her feel guilty. She’s now in expensive analysis, trying to understand why she has trouble taking responsibility for her income.

Jill does think money equals responsibility. But she and her husband have different values, and they’ve got big problems. She comes from a middle-class family who lost all their money in the Depression. For her, saving is a virtue. Jill, however, is married to an English immigrant, a carpenter who despised his father’s being a tightwad. He also likes to drink and play the horses. Depending on how things are going in the relationship, he contributes $150 or $200 a week to their monthly budget of around $2,400, but he keeps $250 a week to spend on himself. Much of the money Jill earns goes to pay for child care and a therapist to figure out the relationship. “He calls me cheap. I call him a wastrel. We could be saving $10,000 a year and we’re not.”

But would it really help if Jill had more money coming in? “It’s convenient to blame money,” she replies. “But I’ve come to realize that even if we made more money, we’d still have the same bottom-line problems. For me, money represents security; for him, freedom. If I want more money from him, it really means I want more emotional security from him. If he wants to keep more money, it means he wants more freedom in the relationship. My therapist says we’re both trying to manipulate each other into something the other doesn’t want in order to control the situation.”

Whether the security is emotional or financial, a lot of women don’t assume their share of responsibility or risk – especially if they’ve grown up thinking men are supposed to take care of them. Inordinate interest in money is somehow unseemly, relegated to gold diggers, “not nice.” Even the most die-hard feminist can become locked in a soap opera of ambivalence and dependence.

Yet how different it is when Daddy expects his daughter “to think like a man.” Take Dana. She is a crackerjack real estate broker, taught how to handle finances by her father, a lawyer and investor. Her husband, Paul, is an award winning, best-selling author and successful television producer. Between them they have seven bank accounts. Since they married nearly two years ago, Paul boasts he has not made one trip to the bank. “Paul doesn’t know what he’s doing with money, so I do it all,” Dana says. “If you asked him how much money we have and where it is, he wouldn’t know. I pay his bills from his accounts.”

But when Paul needs money, what does he do? He laughingly explains, “I tell Dana I need some and then I go into her purse and get it.”

Now, what would Freud say about that?

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments