On a steamy afternoon in Miami Beach, not far from the poolside table littered with five suntan lotions with labels in three languages, the dour former head of the Spanish F.B.I. is deep in conversation with a onetime director of creative projects for CBS Records International, an exotic halfblack, half‐Japanese woman who is a close personal friend of Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder. The unlikely duo travels the world together, from Miami manse to Argentinean rancho deluxe, from recording studios in L.A. to TV studios in Singapore, from M.K. in New York to Regine’s in Paris or Coconut Grove. Their Christmas‐card list numbers 10,000; they are conversant with the wines one can take to China without significant taste loss in flight, and they can produce the phone numbers of the Miss Universe finalists of a dozen countries. Should the need ever arise, the majordomo, Don Joaquin de Domingo, is perfectly capable of directing a major anti‐terrorist operation—he is to security what Orel Hershiser is to pitching. Shirley Brooks need only whisper to get Michael Jackson to come to the telephone. Like Fernando Bilbao, the roadie turned pilot who trained for a decade in anticipation of commanding the jet he now flies, they each have a single mission: to keep their restless boss, that world‐class crooner and swooner Julio Iglesias, happy.

They are not alone, of course, but simply the apex of a carefully chosen entourage—fifty to eighty who maintain an intricate operation that costs a cool $700,000 a month. All out of Julio’s hand‐tailored pocket. Iglesias is billed as “the most popular singer in the world,” and if only for the energy it takes to keep hordes of adoring women at bay whenever his lavishly outfitted, $14‐million‐plus Gulfstream III touches down, theirs is an exhausting existence. On the battlefields of paparazzi and autographs, hair spray and headlines, they have been involved in a harrowing seven‐year war. For, since 1983, the forty‐six‐year‐old Iglesias, divorced father of three half‐ Spanish, half‐Filipino teenagers, has been embarked on a manic middle‐aged quest: to conquer America as no other European entertainer has before—not Maurice Chevalier, not Charles Aznavour, not Yves Montand. There is one formidable hurdle, however: LEFL (Leaming English as a Foreign Language).

“What means ‘love jones’?” Julio Iglesias asks a few days later while being driven down Sunset Boulevard to a Los Angeles rock station at the ungodly hour of 9:30 a.m. He’s glum. Ordinarily a planetary star of Iglesias’s stature shouldn’t have to make these visits. But he’s never gotten the recognition of a young audience nor the respect of the hip in Hollywood that results in automatic airplay on the radio. So, like an aging screen siren forced to test, he is obliged to call on these snickering screamers who play humiliating sound effects in the background while they interview him. He’s just heard D.J. Rick Dees announce on one of Los Angeles’s most popular morning radio shows that “Julio’s on his way,” that “he’s got a love jones and he wants to be rubbed down!” Then, pow, bang, cymbals and titters. Great. As if the females of the world needed any encouragement.

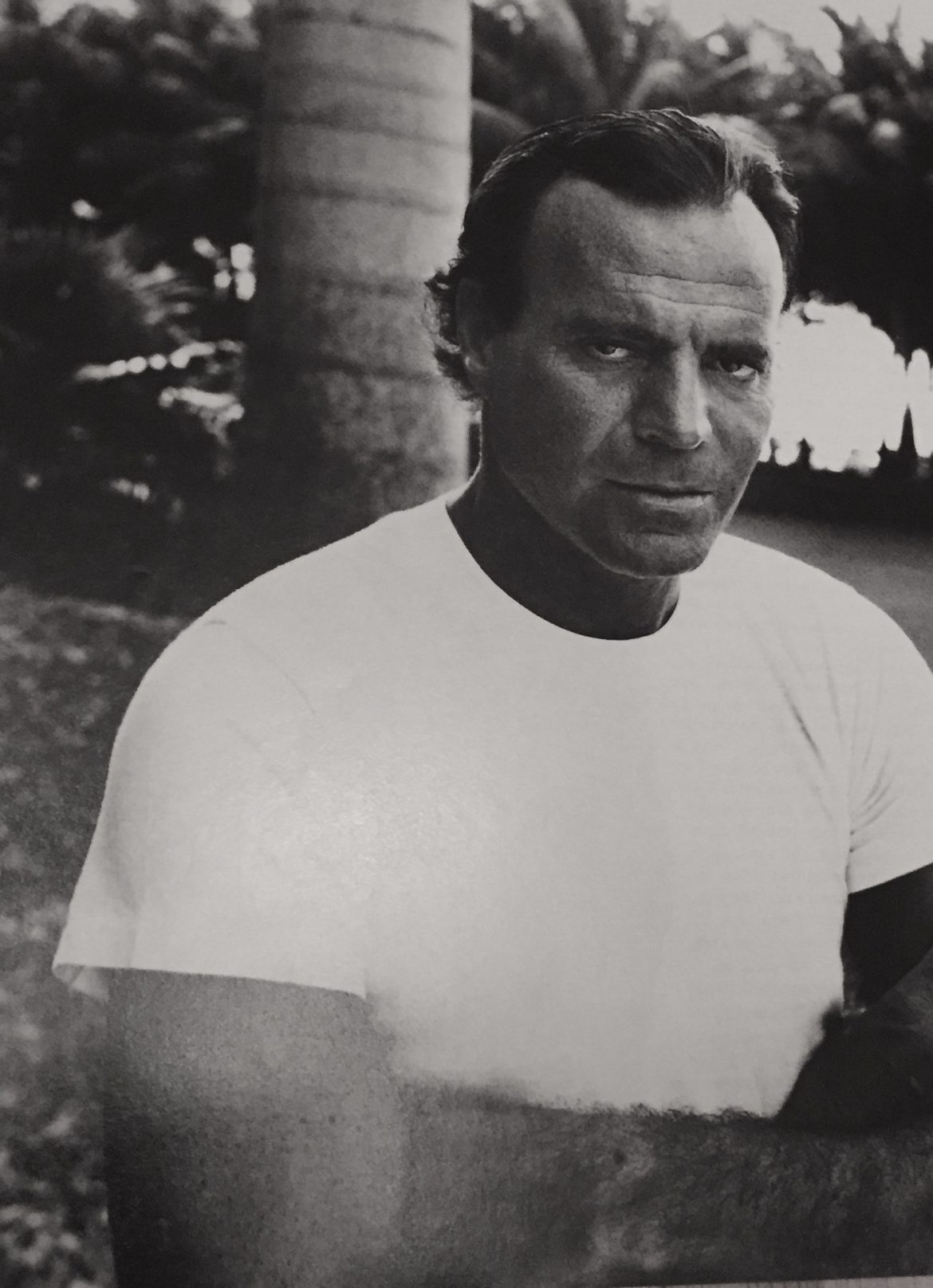

When Iglesias strides into the station in his trademark blue blazer, white T, white cotton pants, transparent white socks, and fragile white gillies, he seems slightly surprised that it takes maybe two minutes before it really starts, but then the women begin pouring out of the walls like cockroaches and the kissing begins. Julio Iglesias denies no one. One of the first to get pecked is Mrs. April Ames, mother of D.J. Hollywood Hamilton. “See, the mother likes me,” he whispers ruefully. Mrs. Ames is one of those who fly in from Vegas just to see Julio Iglesias perform at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles. The last time, she even managed to drag her son along. It’s such a bitch to get Hollywood Hamilton to consider giving him airtime that there is no way his mother is not going to get a full Julio: hugs (five), autographs (three), kisses (four), on both cheeks (one), poses for the Instamatic (two), poses for the Nikon (five), hot breath in the ear (one), pats (nine), squeezes (three).

In the studio, while the sound engineer fiddles with the equipment so Iglesias can make a promo for the station featuring shrieking women in the background, the star feigns interest in the morning newspaper. And then when the gaggle of giggling women paw and scream at him as told, Julio Iglesias, to his credit, turns beet red underneath his deep dark tan and gives a look that implores, “Get me out of here.” At the elevator door a young Hispanic woman rapidly opens and closes her tight jacket while simultaneously jiggling her two very large best friends. “Julio, Julio,” she cries in Spanish, “come with me.” Mercifully, the elevator door closes, only to leave the high‐gloss, six‐foot, 160‐pound crooner pinned against the wall by a 200‐ plus‐pound female reporter breathing heavily. She interviews him all the way down to the lobby, snaps her notebook shut, and waits to get bussed.

Finally, just as Iglesias’s leased Mercedes reaches the pay booth of the underground garage and it feels safe to perhaps at least rest his head against the seat, the young black woman attendant leans in with a parking stub, reaches across the driver’s face, and says, “Mr. Iglesias, can I have your autograph?”

Somehow it never stops. How else to explain an ordinary sparrow that hops onto his table back at the hotel and begins to eat bits of tortilla out of his hand? The answer is it has to be a female sparrow. But Iglesias, his breakfast of one chilled Heineken, two Japanese vitamins, huevos rancheros, and a halfpack of Marlboros over, barely notices, so weary is he on mornings like this.

“America has always been my illusion,” Iglesias told a group of foreign journalists the day before. “But I don’t think it’s been a great time in my life these last several years.” In mid‐1988, for example, he was deeply disappointed by what he viewed as the “failure” of his English‐language LP Non Stop. It took close to three years to make, and cost $3 million in studio time alone. But neither a “socially conscious” duet with Stevie Wonder, “My Love,” nor “Ae, Ao,” an upbeat dance song remixed with a hotter beat by the talented producer of the Miami Sound Machine, Emilio Estefan, became a hit single here, though both songs were huge in Europe. Non Stop sold an impressive 1.2 million records in the U.S. and more than 3 million worldwide, but that is not enough for someone who is used to eight‐figure sales—not enough for a conqueror. This month, however, he’s scheduled to go back into the studio to record a new album in English. He promises this one won’t take so long—he wants it out by summer.

“I’ve been forcing myself to reach things I couldn’t achieve,” a winsome Iglesias sighed to the assembled journalists. “For a non‐Anglo‐Saxon artist to reach an Anglo‐Saxon audience is quite impossible; to be on the radio is very difficult.” As usual, after a half‐hour of public soul‐searching and selfdeprecation, Iglesias had the most hardened scribe behaving like the morning’s sparrow. Poor Julio. He’s so rich and famous but soooo vulnerable. How can we help him? No wonder his audiences want to mother, smother, and “rub him down.”

The tender, urbane charmer is in fact a fanatical workaholic, a largely selfmanaged mini‐conglomerate who gives interviews for a living and assumes, probably correctly, that at night thousands of babies are conceived with him in the background as music or fantasy. “I know they use me sometimes to make love,” he says simply. “I understand you can make people dream,” The dream‐maker is a driven man. Often as not he leaves a concert and goes straight to his Gulfstream to continue circling the globe, alone. Twice in his life he has had to overcome seemingly impossible odds to survive on his own exacting terms—once at age twenty, when he was nearly paralyzed after a serious auto accident, and again more recently, when he has had to learn not only to speak in English but to phrase, stay on pitch, and convey emotion while singing to a foreign beat. For his first big hit here, the 1984 duet with Willie Nelson, it took him six months of intensive practice not to sing, “To all the gulls I’ve loved before.”

Iglesias has recorded more than sixty albums in six languages which have sold more than 150 million records worldwide. Last year Forbes ranked his earnings eleventh among all entertainers, with a projected gross for 1989 of $22 million. In the rarefied world of mega‐stardom, Julio Iglesias outgrosses Kenny Rogers and Frank Sinatra; Neil Diamond, to whom he is most often compared, does not even appear on the list. He is certainly one of the richest entertainers in the world and most assuredly an international sex symbol. When he enters a restaurant you can literally hear the women’s forks drop. But of course this is not enough.

He wants to be immortal.

To explain his obsession, in which idolization triumphs over intimacy, Iglesias has constructed a peculiar vocabulary. “The lights,” for example, refers to fame and recognition, as in “I prefer a life with lights to a life with friends. I would prefer to be onstage with seven thousand people than have a relationship with one,” or “It is not easy with the lights in your eyes to share the lights with others. If you have the lights and they don’t deserve it [sic], you cannot share it and they become crazy.” Iglesias means never to have the lights dim, not on his music or his memory. “America has only five great stars,” he points out, “and all except one are dead: Elvis, Marilyn Monroe, John Kennedy, James Dean, and Frank Sinatra.” It is a pantheon to which he aspires. “When you have a profession that reaches the people, you are so selfish sometimes that you want them to love you even if you die.” He adds, “When I die they’ll read, ‘He didn’t want to.’ ”

Given his aspirations, the controlled chaos that surrounds Iglesias is inevitable. So it’s really no big deal that on a humid afternoon back in Miami a helicopter is buzzing over the four acres of lawn surrounding the two‐pooled, thatched‐roofed waterfront mansion on posh Indian Creek Island (one of several residences on several continents); that boats with madly waving gawkers cruise by; that two still photographers are hiding in the bushes so they don’t get picked up on the cameras aiming toward Good Morning America’s Joan Lunden, who will receive one of ten interviews the star will conduct this day.

Julio is explaining to a TV producer that, no, he’d rather not mention the two Rolls‐Royces and the red Ferrari parked in the circular driveway out front—”So I have too many things in my life. It’s just that I have no garage at this house.” Forty yards across the lawn, under the thatched pool hut where a lunch of arroz con pollo will be served (the Tahitian touches are the architectural remains of a now ended love affair begun in the South Seas), his European houseguests are hilariously recalling just how unprepared the skinny kid was who won his first song contest in the summer of 1968 in Benidorm, Spain. Here was this ex‐soccer player and law student who had nearly died in a car crash a few years before, the son of a prominent Madrid gynecologist, the grandson of a Franco general, who had written exactly one song. Onstage he stuck his hands in his pockets and couldn’t even keep time with the band. But, of course, he did have an enormous will to win and, more important, that unique X factor that carried the emotion of his music right across the footlights. Within four years Julio Iglesias had composed and recorded a batch of hits and had methodically conquered Europe, one country at a time. His criterion for success was being listed under his own name in record stores and not as a “foreign artist.”

Iglesias went on to gain renown in Latin America and Asia, no doubt aided in the Far East by his tempestuous seven‐year marriage to controversial Filipino beauty Isabel Preysler (currently married for the third time, to a Spanish banker‐politico, and viewed in Spain as a kind of cross between Bianca Jagger and Yoko Ono). Although the union, which ended in 1978, produced two sons and a daughter, it was later annulled by a liberal Catholic tribunal in Brooklyn. Today, Julio Iglesias is one of Spain’s most famous exports. “I have worked my ass off, darling. I deserve it.”

But suddenly something is going terribly wrong. Iglesias’s press aide races across the lawn and completely ruins the TV cameraman’s shot. “The wrong side”‘ he yells. “The wrong side. Stop! Julio Iglesias is never shot from the left.” Indeed, when he appeared on the Larry King Live show on CNN, Iglesias became the only guest ever to switch chairs with the host. He reportedly even maneuvered then President Reagan around so he and the other Great Communicator would be photographed with Julio Iglesias’s right side to the camera. Although it is not apparent to the untrained eye exactly why the right side is so preferable, Iglesias tells a famous photographer that afternoon, “I would have to be completely drunk to let you shoot me from the wrong side.”

Iglesias is also convinced he derives his strength from the sun; he must have two hours a day of tanning, along with a couple of hours of exercise. If it’s a particularly bad day, as it was when he heard the news his friend Anwar Sadat had been assassinated, he may burn every stitch of clothing he’s wearing. If certain people bother him, they too are banned forever. He sings onstage with suit pants cut too short because he was wearing similar pants the night he won the contest in 1968. He refuses to carry money, is driven everywhere, dislikes attending other people’s parties, and is monumentally impatient. Once, when he deemed the water in his Miami pool too warm, he couldn’t wait for the thermostat to be lowered; instead he ordered truckloads of ice brought in and dumped into the pool. And before his first appearance on Johnny Carson, he had his secretary fly across the country with five gallons of Miami tap water because he was convinced the L.A. H20 was ruining his hair.

The consummate Latin lover almost never takes a woman out alone on a date—they can stay home and play Pac Man in his Miami bedroom, which features a large portable model. Or if they do happen to go out to dinner, it can be at only a couple of restaurants in Miami or Los Angeles where he keeps his own red wine stocked. (Champagne has “too much air‐conditioning.”) Going off for a weekend is practically unheard of—the only time Julio Iglesias drives himself is when he wants to hear how a new cassette of his sounds on a car stereo.

But membership on his Rolodex does have its privileges. “You can sleep with Julio and never worry he’ll talk,” says one knowledgeable woman of the man who’s been linked with several Miss Universes, Diana Ross, Priscilla Presley, and scores of starlets. Because he’d like to have more children, Iglesias says that he is not averse to another marriage. “It could happen again. I need there to be something deep, earthy in my life.” But he doesn’t seem to structure things that way. “He keeps his social life real hectic so he doesn’t have to get close,” says his pal Michelle Gillen, an NBC correspondent. “He’s very sincere and doesn’t like to hurt anybody. Women are almost shuffled through, but they don’t seem to mind—women just adore being with him.”

“I don’t think to be a good lover means you have to be so physically,” asserts Iglesias. “Because I don’t have a shape—I am a very skinny, very normal man. But if psychically you can be the greatest lover and you can reach people and give them what they need—I tell you I love the idea! ”

Today, as UNICEF special representative for the performing arts, Iglesias is committed to a heavy benefit schedule that included a week of concerts in the U.S.S.R. last fall. Clearly he does love hugging and kissing children, perhaps because he himself grew up in a home where emotion was not openly expressed. “My parents were not happy together,” he says. But they doted on their sensitive young son, and he tried to intuit their unspoken feelings and to please them. He says that by the time he was thirteen and playing on a soccer team he was a “little standout” who sought the attention of the crowds, “the lights.” At nineteen, while attending the University of Madrid and playing goalie professionally for the team Real Madrid, the lights had taken hold. But his near‐fatal car crash shattered not only a piece of his spine but his athletic career as well.

To gauge his chances to walk again, Iglesias did not believe what his father— who quit his own medical practice for a year and a half to direct his son’s recuperation—told him. He devised his own agenda: being able to walk became an obsession, just as conquering America and learning English have been. “I had to learn to give orders from my fucking brains to my wrist, to my fingers and my toes, to move,” Iglesias recounts with obvious emotion more than twenty‐five years later. He would eat raw meat “to force protein in my body.” He would crawl out to the beach early in the morning and stay in the water exercising his legs for hours. He wouldn’t emerge until everyone had left the beach for lunch.

The family chauffeur lost seventy pounds carrying him to law classes at the university. The patient chauffeur also sat with him on campus while he flirted silently and practiced projecting emotion. “I didn’t want the girls to see I walked with a cane.” Iglesias’s goal was to be able to cross the street against traffic by himself. That was accomplished one day in Cambridge, where his father had sent him to study English for three months. Using the guitar he learned to play in the hospital to while away the time, Iglesias started singing in Cambridge pubs in 1968.

He returned to Spain in time for the song contest, once again aided by his father, who plastered his son’s poster around Benidorm. (In 1981 Iglesias’s father was kidnapped and held for twenty‐five days by Basque terrorists. He was freed in an operation directed by Joaquin de Domingo, then the director of Spain’s anti‐terrorist police force.) Similarly, when Iglesias decided to stage a major breakthrough into the U.S.’s competitive music market in 1983, he confronted the challenge as if it were a military campaign.

Aided by the deep pockets of CBS Records, as well as the star himself, publicists Rogers & Cowan spared no expense in letting the press know about Julio Iglesias. He was launched on Hollywood’s A list at a party Ann and Kirk Douglas threw for him at Chasen’s. (Warren Cowan was best man at the Douglases’ wedding.) In turn Iglesias was the entertainment at a benefit for the favorite Douglas charity, Technion, the Israeli institute of technology.

“Johnny wanted him after Kirk and Ann,” reports Cowan of Iglesias’s first appearance on Carson’s show, “and at one point I had every single billboard on Sunset Strip lined up for him.” That idea was scrapped in favor of Julio’s fortieth birthday party in Paris—a $200,000 affair that featured junketing journalists from all over the world and photographers standing on tables and kicking over drinks at the elegant restaurant Le Pré Catalan in order to snap the birthday boy with Catherine Deneuve, Jane Seymour, and his pal Regine. Meanwhile, favored female reporters in the U.S. would receive from Iglesias five dozen different‐colored roses the day after an interview, with cards reading, “Nice to see you, love, Julio.”

“They were packaging him in the old‐fashioned Hollywood way and getting people to accept him before he even did anything,” says a woman invited to many early Julio events. “Finally, if you hadn’t been to see him or hadn’t heard him, you were out.” The shrewd pairing of Iglesias and Willie Nelson singing “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before” (reputedly George Bush’s favorite song to jog to and Ed Koch’s favorite to treadmill to) helped propel Iglesias’s first English‐language LP, 1100 Bel Air Place, to quadruple platinum, signifying four million units sold. That was followed by another duet, “All of You,” with Diana Ross (carried on off‐stage as well), which drove the point home: sophisticates could snicker at the tan in the tux, but they loved him in Las Vegas and Atlantic City (since high rollers could park their dates at his shows and hear no complaints as they gambled the night away), and even in Cincinnati. In the U.S., the constantly touring and ever available Julio—who often had his own photographer supply the tabloids—was becoming a household name.

To conquer America, however, Iglesias has to go after middle‐of‐the‐road baby‐boomers without alienating his Hispanic base. Although the potential market is vast—80 million were born between 1946 and 1964—boomers neither buy records nor listen to the radio with the same enthusiasm as teenagers. Says rock manager and industry insider Danny Goldberg, “There are a few people who become superstars to this audience, like Barbra Streisand or Neil Diamond, but the slots are very few. He’s after a big prize.” Goldberg thinks it’s immaterial whether every record Iglesias releases is a huge hit. “What’s more important is that he has access to this audience if he makes the right record. He now has name recognition.”

But Julio Iglesias can never really dominate in the U.S. without a fluent grasp of the language. “When I first met Julio, in 1983, his English was extremely limited, to put it nicely,” says his Hollywood speech coach, Julie Adams. At one point Adams resorted to using a Kermit the Frog puppet to show him how much his mouth needed to be open to form certain sounds. “I knew if he started singing about love on the ‘bitch’ there’d be problems.” By forty his breathing habits and ways of forming words were deeply ingrained, and for endless months of tedious twelve‐hour stretches seven days a week in Miami, Los Angeles, and the Bahamas, Adams would drill Iglesias, not only in correct pronunciation but in the emotions his song’s lyrics were supposed to convey. “There were dark days when we were hanging on by a thread,” she admits, but Iglesias is tenacious. “Now I understand the news and jokes on Saturday Night Live,” he says. “Before, you have to ‘splain everythin’ to me.”

Once he hits the stage, however, very little explanation is needed. “I can fake many things in my life,” says Iglesias. “When I go onstage I can’t fake. It’s the only time my skin gets younger; I don’t have an age. I don’t sing with any nationality.” Instead, he closes his eyes, grabs at his lapels, and clutches his stomach. (To the uninitiated this might incorrectly signal gastrointestinal distress.) Accompanied by an orchestra playing baroque pop and three sexy backup singers, Julio pours out l‐o‐v‐e, clearly savoring every moment. “Sometimes when I’m singing I don’t know where I am. And I don’t take any drugs or wine. Sometimes I feel that I am away away.” Too far away ever to be so crass and American as to ask his fans to buy his latest record, for example. But he must figure they probably will anyway. “Singing is only 5 percent of being a singer. When you reach the emotions, you reach the emotions.”

Amen.

In September, Iglesias went global again with the launch of Only, his signature perfume line—”I sing to millions of women, but in my heart I speak to only one.” Only has gone on sale in sixty countries, including the U.S., where Iglesias himself pitched the woo in a $7 million ad campaign. Myrurgia of Spain, the perfume’s maker, claims it has sold a million bottles in initial orders worldwide, and expects to gross $15 million from the four months it has been on the market. Clearly, Julio intends to give Misha and Oscar and Calvin a run for their money.

Recently, of course, reports have surfaced that Iglesias has been having a hard time accepting middle age, and at the media day for Julio and Only at the Pierre hotel in New York last May, the poster‐size photos of Iglesias serving as a backdrop at the frenzied press conference appeared to be at least eight years old. But he refuses to give up his smoking and his daily sunbaths, both of which are leathering his skin. Instead, in the forty‐five‐minute video accompanying his latest multi‐language LP, Raíces (Roots), he made Brooke Shields, now twenty‐four, his silent love interest.

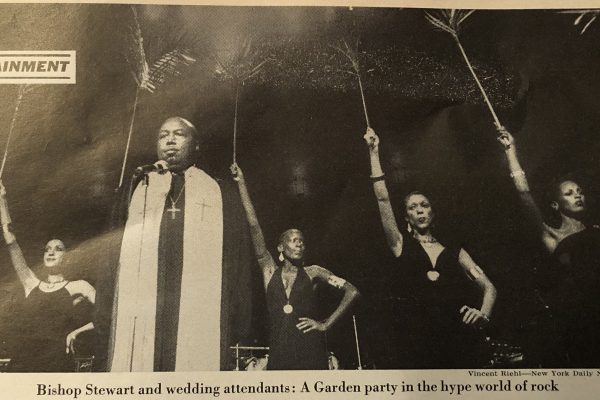

Iglesias’s power over his fans is such that after a concert in Florida—where all of Miami nice and Miami vice mixed in a blaze of sequins and feathers—the backstage hallways leading to his dressing room were a virtual wall of female flesh. That’s not even counting those he received before the show: delegations from “The Original American Fans of Julio Iglesias” and the “National Julio Iglesias Fan Club—A Legend in Our Time,” one of whose missions is “to circulate his scrapbooks behind the Iron Curtain.” He chose to ignore, however, the mysterious Frau Donata of Düsseldoif, a Juliet of the Spirits vision who claims that as a “rich‐born successful businesswoman” she has attended Julio Iglesias’s performances in seventy countries, once flying from Frankfurt to Buenos Aires to catch him live. “Some people buy drugs or have collections of art. We spend our money for Mr. Julio,” she says.

Now even the mayor of Miami patiently waits to pay his respects, caught among women of all ages, colors, and sizes. Several are pregnant; one is pushed in a wheelchair. Right behind His Honor outside the dressing room are a sultry pair of scantily clad twentyish twins, definitely not the Double Mint variety. They get pulled into the room first, along with a tall, green‐eyed colombiana in a matching green Ultrasuede mini‐dress who insists her fat friend in black sequins be allowed in too.

Inside, Julio Iglesias is kissing and posing as usual, and intermittently trying to give a long last good‐bye to a skinny blonde with a braid down her back who held a special front‐row seat. “Tomorrow I wake in my country,” he says, elated to be going straight from the dressing room to his jet to fly to the island of Ibiza, his base for the next two months. His mother, who helps raise his children in Miami and who looks as if she has walked straight off the screen from The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, starchily reminds him that he’s related to several of those being presented. “Sí, Mamá,” he says wearily. “I think by now I have met the whole family.”

Finally ace girl Friday Shirley Brooks (“I do everything with Julio except sleep with him”) reminds him it’s time to depart, but still the hangers‐on hang in. It’s hard to imagine that scenes like this go on more than two hundred times a year. The blonde gets another long hug and Iglesias, looking spent now, begins to fight his way out of the dressing room. A photographer, sensing a good shot, urges the twins and Señorita Green Eyes to approach the white stretch limousine Iglesias has managed to get into. Green Eyes hands her purse to her friend. As the car slowly begins to edge its way toward the exit, two Julio handlers, with effortless, well‐practiced ease, gently catch the beauty and lift her off the ground, long legs and spike heels dangling. Suddenly the limo door swings open and presto! She disappears inside with the star. Will she wake up in Ibiza too?

One has only to recall Iglesias a few hours before, when on his way to the concert he looked down to directly below his belt buckle, dropped to his knees, and passionately declared with a sweeping gesture downward, “As long as I have it all together—the brains and the heart and these eyes—I will never get old, darling, never!

” The fat friend is astonished—and left holding the bag.

Original Publication: Vanity Fair, January 1990

No Comments