Original Publication Vanity Fair, August 1990

For the overpampered, the overperked, the siliconed, and the restless, “Department 2” of Los Angeles Superior Court is always to be avoided. Here in the Hall of Sorrows, as the family-law division is known in downtown L.A., a former perfect 10 must never be seen divorcing among the hoi polloi, hanging out with alien downtrodden awaiting custody hearings. When it comes time to sever the marital knot, the least one ought to get, by God, is Century City justice. Why brave the freeway when all you have to do is tell that lawyer you’ve paid the $10,000 retainer to, the guy who’s charging you $400 an hour to make sure you get the tropical fish and the African violets, to call up a Rent-a-Judge to hear your divorce? Get a geezer, one of the forty distinguished retired jurists of Los Angeles County the law permits you to retain for $300 to $500 an hour. If you like, he’ll bring his own court reporter, and there won’t be any press or sleazy spectators. Just meet him in your lawyer’s high rise on the Avenue of the Stars and get him to listen to those $5,000 forensic accountants trying to unmingle the commingled cash.

Being married and rich in L.A. should mean never having to say good-bye east of Beverly Hills.

These days in la-la land, where community-property laws dictate that everything be divided right down the middle of the tennis court, it’s a toss-up whose business is growing faster: the attorneys drawing up prenuptial contracts, the wedding coordinators, or the judges hired for the divorce. But no matter how you cut the wedding cake, it’s the lawyers who are getting rich. Take Robert Kaufman, for instance. Kaufman, handsome and smooth, is speeding back from the Hall of Sorrows in a hot, brand-new souped-up Nissan 300ZX. One of the stars of the divorce bar to the stars (he’s taken care of Bob Dylan, Ali MacGraw, Jaclyn Smith), Kaufman passed on Roseanne Barr as a client because she was too difficult. This is in spite of the fact that Barr has a good shot at the ultimatestar income, what is known in the trade as “syndication Valhalla.” One hundred episodes of her TV show could land in the can, to be syndicated around the world over and over again until she causes a global headache, but not before earning her $15 or $20 million easy, not counting her salary. Think of the challenge of her prenup. It could run, as they sometimes do, to fifty or a hundred pages. Think of the amount of community property to be held back, the fee Kaufman could charge. Never mind. Not only did Barr’s new husband, Tom Arnold, refuse to sign, but Kaufman himself wasn’t very interested in getting involved at this point. “Usually I tell people who ask me to supervise their prenups to save me for the divorce.”

Just now, Kaufman, who like many successful practitioners of L.A. law seems to identify with the status of his clients, is on the San Diego Freeway, apologizing for not driving his usual Ferrari or Porsche. “I got tired of being ripped off,” he says, gunning the engine. “This one has all the same bells and whistles, it’s just not so well known, so I hope it’s safe.” The car phone rings. He deals with an emergency—a father refusing to produce his young son for a visit with the divorced mother. Due to his wealthy parents’ drug intake, the child was born with a fatal medical problem and is not expected to live more than a year. But Kaufman is used to the moral lapses of the rich—most of the time they keep him in business. Right now he is negotiating for Ed McMahon’s estranged wife, the former flight attendant Victoria. All of Hollywood knows that she was allegedly cheating on Ed with an L.A. policeman. But California is a no-fault state, and even after all of Johnny Carson’s woes, McMahon never had a pre-, or a post-, nuptial agreement. Before a final settlement, Victoria is collecting 50,000 tax-free support dollars a month. Not only will Kaufman now fight for half the McMahons’ current community property, he will also try to determine what future moneys will come to McMahon as a result of the “celebrity goodwill” built up during the thirteen years of the marriage. Celebrity goodwill is a hot new property in the heavily hoed field of divorce. Essentially it means that whatever worth as a “fame package” McMahon is determined to have accrued while he was married will be considered fair game in determining how much the divorce settlement should be.

Such aggressive tactics send a lot of rich people straight to the drafting of the prenuptial contract for their next marriage. “With high-income people you’ve got to have it,” says a multimillionaire producer currently married to a TV personality who also earns big bucks. “I can’t think of anyone who doesn’t. And the reason you’ve got to have it is because of some very, very high-powered attorneys who specialize in divorce and tread on people who are tender and volatile—if anybody settles, they lose.” He maintains that if such pacts are done fairly they are ”never brought up again and never thought of again. It’s not unusual to say, ‘You know what? I love you, but it’s taken years to build up my estate, and if for any reason the bliss we have today is not there three years from now, well…’ ” So that in parting, ”$50 million would not be taken away three or four years later. It’s not at all unusual.” Particularly when considerable fortunes are at stake. None of billionaire Marvin Davis’s children marries without them, for example, nor does Johnny Carson—anymore. Richard Pryor always seems to be in the midst of signing or invoking one.

Prenups are so trendy in Hollywood that one attractive redhead, Beverly Hills hairdresser Shelly Carmichael, has been asked several times if she’d sign one, sometimes after a few dates, once by a Mexican immigrant who was protecting a humble bungalow. But not everyone, even those actually on the threshold, is eager to play ball. Every other person on Rodeo Drive has a story about the ice sculpture melting at the fancy reception because the bride wouldn’t sign. It’s just so awkward all around—trying to package the emotional explosives of money, sex, and power all into the same dry document. The consequences of the Beverly Hills mantra of the moment, ”What’s mine is mine and what’s yours is yours,” are rampant evasion and denial.

”If a guy with $10 million decides to marry a woman ten or fifteen years younger, she probably hasn’t focused on the economics of the situation other than knowing it’s going to be a nice life,” says prominent Century City divorce lawyer to the stars Dennis Wasser. “Now, that person sits down and realizes all the assets are going to stay separate property— that puts a new perspective on the person she’s marrying. Conversely, the one with the money almost always thinks he’s being married solely for his intellectual capacity, charm, or whatever, and then he realizes the other person is also interested in the economic aspects of the marriage, and that’s very terrifying.”

So the prenuptial contract, now as seemingly indispensable as the marriage license, is a deeply embarrassing and highly controversial topic, particularly for women, not easy to broach and rarely discussed outside the inner sanctum of the counselor’s chambers. Never among friends, and, hey, if you really want to throw ice water on romance, bring it up in bed.

Imagine looking a lot like Julia Roberts or Kim Basinger and having to acknowledge that in sound mind and, probably most important, fab body you are in fact—with the counsel of an attorney who drives a Porsche—waiving most, if not all, of your rights to what you and your spouse might work on together: a house, a career, whatever. You take yourself out of circulation in exchange for stepping up to a life-style where, say, spending $60,000 or $70,000 a month is just a few new landscaping specialists and another personal nutritionist. In essence you begin your honeymoon with a trip to Forest Lawn by signing a document that determines what you’ll get if the marriage ends in death or divorce. No wonder a tool of the trade among those who write prenups is the “cover-your-ass letter,” avoiding malpractice disputes later by making sure the signee knows exactly what she or he has done.

On the other hand, it’s easy to see why the haves insist that the have-not intendeds sign on the dotted line. Just look at poor Steven Spielberg. He naively drew up an ad hoc prenup with Amy Irving on a little piece of paper, just between the two of them. But he quickly learned when he wanted to divorce Irving and fly into the arms of Kate Capshaw that such a contract would never stand the scrutiny of the court. Irving got millions and millions more than she would have if the contract had been valid. Tom Cruise and Mimi Rogers didn’t have a prenuptial of any kind. Neither did Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden. Under the law, Hayden, like many California men married to female high-earners, was entitled to a bundle. But perhaps because Fonda had poured more than $20 million into causes that directly or indirectly benefited his political career, the liberal Hayden, who always claims he wants to be poor, took millions less than his share of the community property accumulated during their seventeen-year marriage.

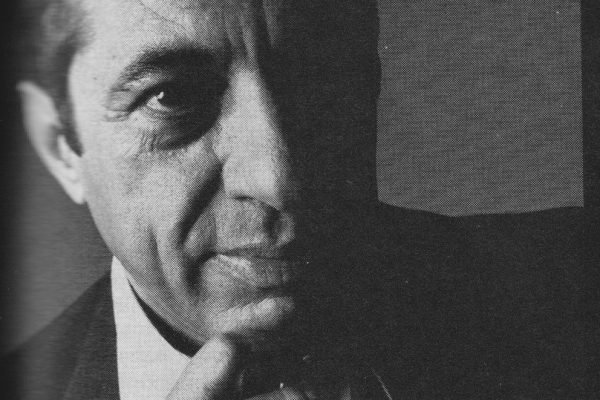

‘What ever happened to love, cherish, honor, to have and to hold from this day forward?” thunders Marvin Mitchelson from behind the gargantuan desk which rests underneath the illuminated copy of a fragment of Botticelli’s Venus placed in the ceiling of his Century City office. “I’ve never seen a prenuptial not end in divorce. Women are fools to sign these things!”—unless Mitchelson is the one drawing it up, so it’s guaranteed to be “fair.” Mitchelson today is like the Pete Rose of divorce attorneys, largely discredited by his peers. But while it’s chic to sneer at him, a large number of the divorce lawyers in town owe easily half their community property to Mitchelson. For back in 1976, Marvin Mitchelson—while representing Michelle Marvin, the tossed-aside companion of Lee Marvin—begat palimony. And palimony begat in very short order living-together contracts. Some L. A. Lotharios were so nervous after Marvin v. Marvin that they actually had waivers on their nightstands for sleepover visitors to sign. The rush toward prenuptials has been burgeoning ever since.

Does Mitchelson recall the very first prenuptial he ever heard of? He thinks for a moment and then jumps up from his desk. “Oh, why didn’t I remember this for TV!” He races out the door, past his marble bathroom, and comes back with an antique leather file folder. Inside are two rare documents both dated 1801, both signed by Napoleon. One is a property settlement with Josephine for 12,000 francs. The other is a marriage contract that Napoleon signed as witness for one of his officers. “There’s a dowry up front and there’s property division here,” says Mitchelson, pointing to the faded French script, “various things that don’t put the woman out on the street, so to speak. It’s fair.”

“Fair is different than equal,” says Century City lawyer Patty Glaser, who handles the divorces of megamoguls like Kirk Kerkorian. “By law, fair is 50 percent of the community property. The prenuptial agreement is intended to alter that state.” The essence of tying a mutually satisfactory prenuptial knot, then, is to get beyond unfair, a concept with a revolving definition. “These days the woman has to be good in every room of the house—it’s an incredible strain—to be smart, to look good, to make your own money because nobody wants to take care of you anymore,” says Madeleine Bazovsky, a self-described ex-trophy wife and veteran of two prenups. “A trophy wife, a showy ornament for the man, lasts for the most about fifteen years. Look at Ivana. She started to look hard and that was goodbye. In my group we were all trophy wives and we all got dumped at forty. If the woman is smart she’ll get taken care of at the time of the wedding, when he wants her. If she doesn’t put clauses in for herself, get some property at the beginning, she’s a moron. My ex-husband would say, ‘Why don’t you become a lawyer?’ or this or that. At the same time he’d say, ‘Darling, pack your bags. We’re leaving for Acapulco.’ Well, I can’t be in law school and in Acapulco at the same time.”

Bazovsky made sure her last husband, a wealthy builder, agreed to make a down payment on four condos for her before she consented to sign the prenuptial. “You have to these days. Everybody has higher expectations for shorter periods of time. I’ve held on to the rentals for fifteen years and now they’re worth two million, but two million’s not much out here. So can you imagine those women who sign agreements getting $20,000 for every year they’re married? Where do you go with that? It’s a slap in the face.”

Trophy wives need to understand they live by specific rules even if they are unspoken. A number of lawyers, however, mention that they have been asked to include in the prenup what weight these women must maintain, how many times they have to exercise per week, and the minimum number of times per week they are expected to have sex. On the other hand, wealthy women protecting their assets in prenups also ask for perks such as being taken out of town at least one weekend per month and prohibiting their husbands from being couch potatoes. “These things never stand up in court,” says a divorce lawyer, “but they like them for the emotional incentive.”

Liv Faret, a tall and striking former model from Norway who was married to producer Michael Phillips (The Sting, Taxi Driver, Close Encounters of the Third Kind), has never gotten over the fact that when she was already pregnant with their daughter she signed two legal agreements at the same time: a living-together arrangement which gave her $25,000 if the relationship dissolved, as well as a prenuptial agreement which promised her slightly more if she married Phillips, which she did a very short time later. “It ruined the whole marriage because it gave one party the upper hand,” she says. “It fosters fear and insecurity. I was quite dispensable. I could leave without making a dent in his life.” After the marriage a major sticking point was the fifty pounds or so Faret gained in pregnancy and defiantly never completely lost. “As soon as I got as big as he was, he got threatened.”

Perhaps the most intriguing question is why Faret, a university graduate with three producer’s development deals at the time, felt compelled to sign such an agreement. But that was part of the problem. She thought she was on her way to having a career. “What happens is you get embarrassed. I was embarrassed even in front of my own lawyers, who told me I should be asking for more. I wanted to sweep it all under the rug. At the signing everybody had champagne. All these guys were celebrating and I felt ridiculous. I felt like the sacrificial lamb. My only consolation is that other women are equally stupid.

“Michael told me that the agreement was only a token of trust, that it would be torn up immediately after the marriage. So after we were married I said, ‘Let’s throw it out—we had a deal,’ and he said, ‘Gee, no, it isn’t working out as I thought, I don’t think so.’ ” Phillips himself says that he had reservations about the marriage from the beginning. “At that time, I did not feel confident enough in the long-term prognosis to proceed without a prenuptial contract.” Finally, Faret says, she did manage to negotiate a postnuptial agreement which gave her half the increase in value of their Beverly Hills mansion and other goodies worth over a million dollars. Soon after they reached that agreement, however, she stopped going to their marriage counselor and the six-year marriage ended with a bitter divorce. “It’s like getting a job with a big title and no increase in salary or benefits,” says Faret, who thinks women should never sign an agreement they aren’t completely happy with. “The sex and the money are connected in the mind of the man. A woman could be the best mother, wife, or hostess, but it only counts what you do at night when the lights are turned off. They want the earth to move.”

“You have to be cautious,” says Spago regular and bachelor-about-town, TV-commercials director Danny Vinokur. “I’m a marketing guy. I look at trends and what I’ve seen with my friends is that being idealistic and romantic could probably cause problems. I’ve seen nice guys with money who wanted prenuptial contracts and they were cried out of it. And you know what? All of them were taken. I hear girls talking about other girls who are ‘on the dollar plan.’ These are the women who get ahold of a guy’s credit cards and spend thousands before the guy realizes what’s happening.”

To prevent these “accidents” or surrenderings, the agents, business managers, and attorneys of L.A.’s rich and powerful think that prenuptial agreements should be mandatory for all their clients, male and female. Business-manager-to-the-rich-and-famous Fred Altman explains that his office even offers an option to revoke the prenuptial after a certain period. “We have a provision that can be inserted stating that if the marriage is still there after three years, either or both have the option to convert from separate to joint property.” And how many takers have there been? “So far none.”

Actor James Woods considers lawyer Dennis Wasser his “new best friend” because Wasser got an airtight prenuptial for Woods when he married Sarah Owen last year. “Dennis put it up on his bookshelf. I said, ‘Aren’t you supposed to file those?’ He said, ‘No, it’s just inventory for the bookshelf. I know this woman, and you’ll be back here within six months, and she’ll be after you for a lot of money.’ He was off by four days.” According to Woods, the marriage fell apart shortly after the wedding coordinator and her husband introduced Owen to another man. The prenuptial agreement “saved my life,” he says gratefully. “My life would have been a sheer and utter disaster without it.”

Because they are so heavily weighted toward the “haves,” and because they are at odds with California’s community-property laws, prenuptials are very heavily scrutinized by the courts, says Judge Richard Denner, of Los Angeles Superior Court. And they are often contested, “because you might as well give it a shot.” But if the prenuptial was signed at least a month before the wedding, drawn up by competent lawyers, full disclosure of assets was made, and both of the people involved are considered “sophisticated,” it will stick. At age twenty-three, Cristina Ferrare signed a prenuptial contract before marrying John DeLorean, who was twenty-five years older. When she sued to have the agreement overturned twelve years later, she lost. Why? The court said that she was “no babe in the woods.” Explains Judge Denner, “What you’re looking for is someone who is sucked in or didn’t understand or who was pushed.”

Somehow, not that many of the glitzy Hollywood rich and those they marry fit that particular description. To make life in this mistrustful and litigious fast lane easier, though, Dennis Wasser advocates turning the wedding bonds into a typical Hollywood deal: putting the whole marriage up for option at regular intervals. “Why not have a marriage contract with options to renew? Let’s have a five-year contract and if you want to renew it at the end of five years, sit down and negotiate it.” Such a system, Wasser believes, would alleviate a lot of fear about merging sex and commitment among the edgy heartbreakers he represents. “I now have people coming in saying, ‘What do I need? A waiver on herpes or AIDS? DO I need a health form?’ Because now we have lawsuits by one person accusing the other of giving that person these diseases. Next we’re going to have to have waivers on this or we’re going to have videotapes of the parties discussing their sexual relationship—put it on tape as a record so we know whether or not there’s disclosure.”

How has it all come to this? “I think our society is really focusing on an inability to have intimacy,” says Beverly Hills attorney Lance Spiegel. “Let’s be realistic, you know. Things don’t go on forever. Divorce can be very expensive and so let’s keep our space.” “Americans are so litigious it’s a way to carve out an area where we’re not going to fight anymore,” says Patty Glaser from behind a black marble triangular-shaped desk that once belonged to Johnny Carson. “Divorce has become so ugly. You sit there and you can’t believe what people say to each other. It’s a joke this is a no-fault state. If you can’t get the stuff out about the affairs, the drugs, and the alcohol abuse because of no-fault, you get it out when you fight over child custody. People fight over hand towels in guest bathrooms! I did not go to law school for this. The reason I encourage prenuptials for everybody is because there is such pettiness and anger in divorce. If you can take something ugly out of divorce, you are doing a service for society.”

Mother Teresa and the pope may not agree, but this is Hollywood after all, where the only true romance may be up on the screen. “By the time you’re ready for your second marriage,” says a newly engaged CAA agent, “you’re not willing to give away what you earned the first thirty-five years of your life.” In lotusland, where everything else is consistently overhyped, the expectations that a marriage will become a blockbuster don’t seem to be very high. “I’m like the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun,” says a recently divorced agent about to take another marital plunge. “I aim for the stars but I hit London.”