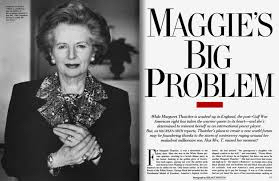

Vanity Fair – June, 1991

For Margaret Thatcher, it was a throwback to the glory days. Here she was in the White House private quarters, reveling in a lavish dinner party in her honor, basking in the golden glow of twenty-four-inch tapers, gazing out over the perfect pink and fuchsia roses floating in crystal bowls, the centerpieces on six tables for ten. Only hours earlier, in the East Room of the White House, George Bush had awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor. He had praised “the greengrocer’s daughter who shaped a nation to her will,” and concluded, “Prime Minister, there will always be an England, but there can never be another Margaret Thatcher.” She raced from that exquisite high up to “the Queen’s Bedroom” to change into a long black pleated skirt and brilliant red-and-black brocade jacket for cocktails. And now America’s most powerful leaders were getting up to pay her homage. It was as if the colonies had not yet heard the news of her unceremonious sacking as prime minister last November by the members of her own Conservative Party. Barbara Bush rose to toast the new baronet, Sir Denis Thatcher. “They broke the mold when they made you, Denis.… As the spouse of a powerful leader, you do it better than anyone.”

Sir Denis graciously thanked his hosts and quoted Mark Antony “upon entering Cleopatra’s bedroom: I did not come here to talk.”

The evening was, quite simply, divine. Former secretary of state George Shultz gave the former prime minister advice on agents for her memoirs; she confessed to being overwhelmed “by my paper.” Her entrepreneurial and controversial son, Mark, let it be known to that other feisty entrepreneur seated next to him, the flame-haired Georgette Mosbacher, that he had made millions in the home-burglar-alarm business. Mark’s blonde Texas wife, Diane, startled some with what appeared to be a try at a British accent. But no matter. Margaret Thatcher was in the inner sanctum of power, surrounded by old chums from summits and Star Wars, there only to administer her massive doses of adulation. Naturally, the lady who had ruled Britain for the last eleven and a half years gave as good as she got, extolling America as “a can-do, will-do society,” and she heaped praise upon early Americans as model social Darwinists for freedom: “self-selected … there were no subsidies here.”

Then suddenly the spell was broken. One of the heroes of the day, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, the unflappable hand that urged boldness in launching and guiding Desert Storm, actually uttered the unspoken name: John Major. It was inadvertent yet totally appropriate to invoke the leader of our greatest Gulf ally, but how could he? So what if the new prime minister was Mrs. Thatcher’s handpicked choice? She gave no indication of distress, of course, but that mention jolted more than a few to focus on the ghastly fate that had befallen her only a few months before. Remarked one guest, “It was as if he had spilled something dirty on the tablecloth.”

Even when life was beautiful now it was cruel. Exceedingly so. As usual, Mrs. Thatcher’s son, Mark, was part of the problem. Now, while acting as her personal manager as she planned a new career in international relations, he was facing a fire storm of criticism from her friends and former advisers that would erupt before long in a Sunday Times of London headline: “mark is wrecking your life.”

To add insult to injury, while Margaret Thatcher was polishing off her chocolate mint soufflé with President Bush, and peering across the roses to British golfer Nick Faldo, and even at the very moment when the president was saying that “she defined the essence of the United Kingdom,” one of the safest Conservative seats in Britain—Ribble Valley—was going down to defeat in a striking by-election upset. And it was all being blamed on Margaret Thatcher and her legacy, the hated poll tax.

Let the longest-serving British prime minister in this century eat cake in America. At home Margaret Thatcher was eating crow.

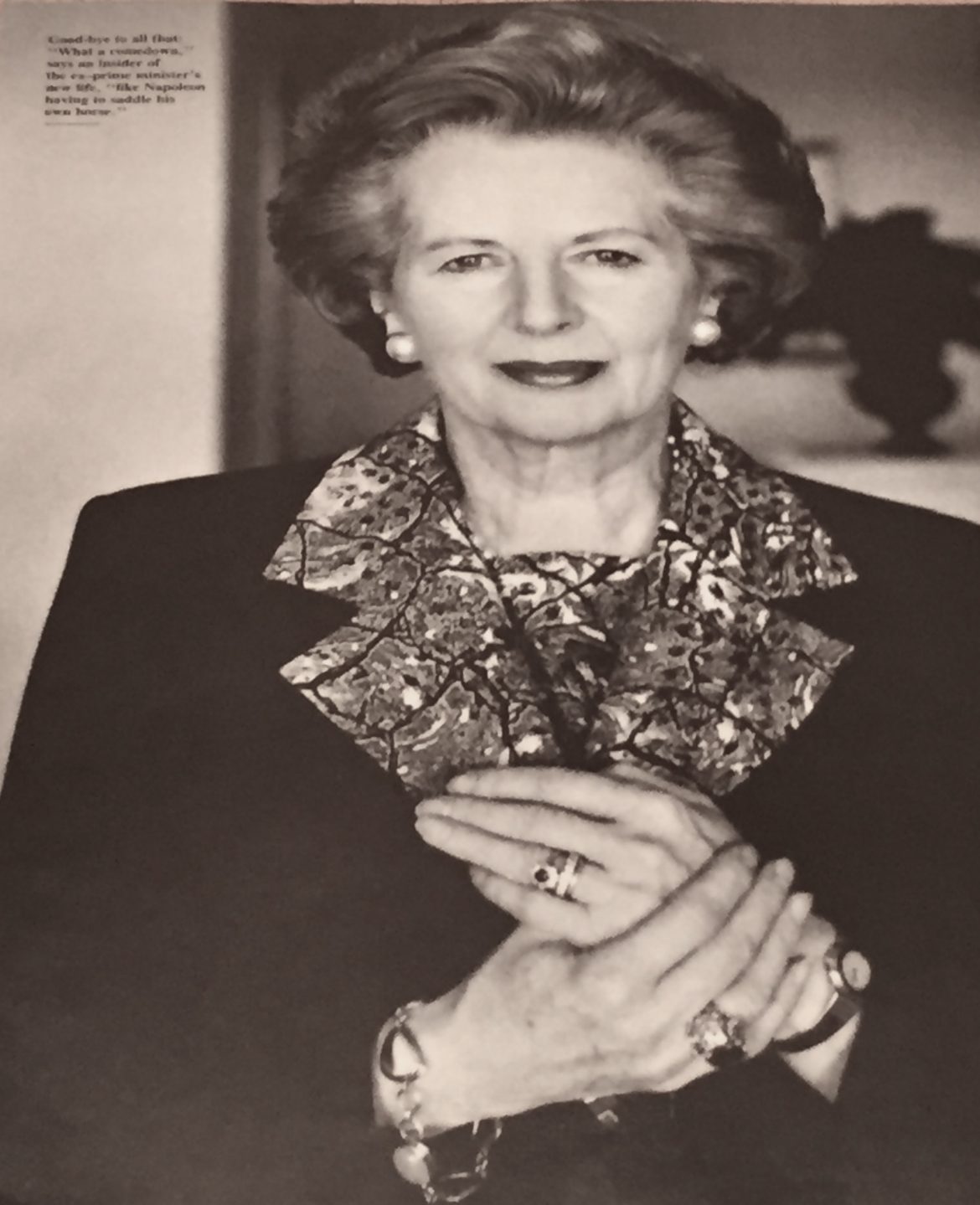

‘The pattern of my life was fractured,” Mrs. Thatcher said the next day in the residence of the British ambassador, referring to her surprise resignation and removal from office. Dressed in a crisp spring suit and her ubiquitous pearls, she plumped all the pillows on the sofa in the decorous drawing room, then sat down and balanced a porcelain teacup in the palm of her graceful hand. She chose her words carefully: “It’s like throwing a pane of glass with a complicated map upon it on the floor,” she said, “and all habits and thoughts and actions that went with it and the staff that went with it.… You threw it on the floor and it shattered.” And the pieces? Margaret Thatcher’s eyes blazed. “You couldn’t pick up those pieces.”

As though the answer to what had happened might be found amid the debris, Thatcher began to recite her daily and seasonal rhythms as prime minister. Mondays, “we went down to the House of Commons for preparations for questions at two o’clock,” she said. “Questions at the House were on Tuesday and Thursday, so on Mondays and Wednesdays we saw foreign statesmen. There were a certain number of overseas events—the economic summit, two European councils. All of this structure happened; you geared your clothes buying to external visits and your conferences. You geared your hair to when you were in the House etc., and then you had a certain amount of entertaining. In June there was the Trooping of the Color, a whole range of engagements throughout the year which became the pattern of my life.” All gone after nearly twelve years, on ninety-six hours’ notice. She paused. “Sometimes I say, ‘Which day is it?’ I never said that at No. 10.”

“She is like a great athlete suddenly confined to a wheelchair,” says Christine Wall, the Conservative Party press officer who was on loan to Mrs. Thatcher for her U.S. trip.

“She wants worrisome problems, she wants to make decisions, she wants to tell you what to do and to save you from yourself,” says another insider. “Now she answers her own phone sometimes. What a comedown that is—like Napoleon having to saddle his own horse.”

“In a sense she hasn’t come to yet from the concussion—everything was so brutal and sudden,” adds Sir Peregrine Worsthorne, a Thatcher loyalist who edits the right-wing Sunday Telegraph editorial page. “She’s pretty shell-shocked still. The Iron Lady has a very emotional side. People underestimate the extent to which she was shattered by this.” The day after Mrs. Thatcher lost a Conservative Party leadership battle and decided to resign in the interest of party unity, Worsthorne got a call from Thatcher’s press secretary, Bernard Ingham: “The prime minister would like to say good-bye.” Arriving at 10 Downing Street, Worsthorne was stunned by what he found. “I went round thinking there’d be a long queue of people waiting to say farewell. I found myself alone. I expected to stay fifteen minutes, which would be quite normal. After an hour, I ran out of conversation. She was very short of people.” On the way out Worsthorne ran into Thatcher’s journalist daughter, Carol. “She had a basket on her arm from the supermarket, ‘bringing Mummy’s supplies’ of cold chicken or something for dinner. It was very disorienting.”

The day before, Thatcher had made her astounding farewell speech in the House of Commons, which even those who consider her a dire enemy regarded as an extraordinary display of political bravura. “She had had that high and had gone off of that,” says Worsthorne. “She had time on her hands. Voilà. The lassitude of impotence had begun.”

Tory Party leadership transitions are known to be less than genteel, but this ouster seemed a classic illustration of the axiom that she who lives by the sword shall die by it. Here was a prime minister known for her prodigious recall, who routinely exhausted her aides with her energy, who every night, no matter the hour, relished “doing her boxes”—locked red boxes filled with confidential papers from every ministry delivered by dispatch riders who would roar through town to deposit them on her doorstep at 10 Downing Street. Here was a phenomenal woman who was devoid of hobbies or interests off the world stage, who once said that taking vacations tends to cause colds. “She wanted us to be like the Japanese,” grumbles one political observer. Here was a leader who, by hijacking the Conservative Party and bending it to her will, had bestowed upon England “Thatcherism.” And if you were not with her in the dismantling of the welfare state and the charge toward privatization, you were mushy, a “wet.” Anyone who couldn’t keep up or who displeased her was ruthlessly sacrificed. “In the United States, she has this reputation as a chaste, saintly figure,” says Andrew Stephen, Washington bureau chief of the London Observer. “In fact she’s knifed every Cabinet minister she’s ever had in the back. That’s how she survived eleven years.”

One of her favorite instruments of torture was Ingham, her powerful press secretary, who would leak to the reporters on the Parliament “Lobby” that certain unsuspecting ministers were in trouble. This penchant for denigration earned him the sobriquet “the Yorkshire Rasputin” from one of the ministers, John Biffen. Biffen, himself later axed, would add, “He was the sewer, rather than the sewage.”

But now it was Mrs. Thatcher who was instantaneously, irrevocably out. “She thought she was unassailable,” says Thatcherite columnist Frank Johnson. “It was hubris. She was brought down by the fault of her virtues—her enormous bravery in battling the most powerful opponent of all, the European Community.”

Others take a less charitable view: “She’d become slightly potty by the end and lost touch with reality,” says one observer. Thatcher’s opposition to a united Europe, and the poll tax—the hated straight levy per head that replaced property taxes to finance local government—certainly helped make her hugely unpopular; in April 1990 her approval rating was 23 percent, the lowest for a prime minister in memory. By November she was stuck at just 26 percent. Many in her own Tory Party were, as Mrs. Thatcher puts it, “running scared,” convinced she would cause them to lose the next election. When the votes were counted in a challenge to her leadership of the party by her ex–defense minister Michael Heseltine, she had a clear majority. But under the convoluted Tory leadership formula, she would have had to submit to a second ballot. Rather than do so she stepped down.

“I have never been defeated” by the people, she said no fewer than five times during our interview. “I’ve never been defeated in an election. I have never been defeated in a vote of confidence in the Parliament, so I don’t know what that would be like.” This last was spoken as if she were flicking an imaginary crumb off her bodice. Moreover, Margaret Thatcher refuses to concede that the poll tax was even an error, and declares that she would have won a fourth election had The People decided. “We had gone through difficult times before. You don’t run scared about by-elections midterm.”

“So if the people had judged your overall record you would have won?”

“Yes. That’s right. But had I gone on we would have had a fairly open split party, and it would not have been easy to get some things done.”

“I’d still be there if I had my choice,” she said at another point. “I did not have my choice, so I decided to do the best thing for my party for the future.… And I knew I’d still have a good bit of influence.”

But what about the unceremonious way she was pushed out, forced to pack up and vacate No. 10 as well as Chequers, the prime minister’s weekend retreat, on just four days’ notice?

“I will suggest that no future prime minister has to do that, because prime ministers have a dignity as ex–prime ministers by virtue of their prime-ministerial office,” she intoned with Monty Pythonish zeal.

Still, there was little humor in her predicament. For months after leaving office, Mrs. Thatcher seemed uncharacteristically frozen in indecision. Her friends tried to cheer her up with a luncheon at David Frost’s, a weekend at the grand manor house of trade-and-industry minister Lord Hesketh, a party at millionaire novelist Jeffrey Archer’s with a cake baked in the shape of the Order of Merit. Even John Major was said to be concerned; when he came to Washington for talks with President Bush before the Gulf War began, he told her American friends, “Be sure to look up Maggie—she’s down.” Those who made the trip found her worried about money: somehow Denis’s comfortable retirement and her son’s reputed millions weren’t going to be enough. Had the leader who had slashed benefits throughout her three terms become too dependent on her perquisites of the state? By American standards, ex–prime ministers don’t get much: an annual pension of roughly $45,000. As long as Thatcher kept her seat in the House of Commons, she was also entitled to her M.P.’s salary of $37,000, one constituency secretary, a small basement office, and a $19,000 cost-of-living allowance. Then, just before Easter, acting on complaints about her financial straits, John Major delivered a golden egg to the woman the London Times had dubbed “the high priestess of self-help”—an additional $53,000 a year to all ex-prime ministers, effective immediately. “It’s very welcome and I’m extremely grateful” was Thatcher’s comment.

Yet the thing she wanted most they couldn’t give her—her power back. Sir Charles Powell, the foreign-affairs private secretary, continued to brief her twice a week until he left government last March. But, after that, one of the best-informed creatures in the universe was reduced to calling government agencies for reports “the moment they are available to the press.”

And no wonder she was so distraught about the whole mess. First, there were 65,000 letters to answer—65,000 that poured in from all over the world in the weeks after her resignation. But she had no real staff, only a borrowed office and a few volunteers who showed up to answer the phone. Then there were her living arrangements—her Georgian manse manqué, on a golf course behind an iron gate in the village of Dulwich, about a half-hour southeast of central London in light traffice, was too far away. She had to find a more convenient pied-à-terre. (Henry Ford II’s widow solved this problem, lending her an apartment in Eaton Square.) Invitations to speak poured in, but who could sort through them? How much should she charge? Literary agents were desperate to deliver bids worth millions for a quick kiss-and-tell. Could she sell them on her notion of a serious historical examination of her era? How should she position herself? If she were to comment on current affairs, would it look as though she were meddling in John Major’s government? How would she raise the money to maintain herself as a world stateswoman? Should she take a job? Now that she was out, would she still suffer the indignity of having Denis’s business affairs questioned and investigated by the press? Since he was now a baronet, might she care to be known as Lady Thatcher? Or should she give up her seat in the Commons, move on to the House of Lords, and take the title of Countess of Grantham, the little town in north-central England where she grew up? How would she stay in touch? Where should she go for lunch? Who’d do the shopping? Who was in charge here? Oh, could Maggie tell them, could she?

As it happened, she could. Mrs. Thatcher announced at length that she wanted to create “the Thatcher Foundation,” devoted to education and research with a focus on “freedom” and Eastern Europe. Characteristically, she would prefer creating her own project to taking a post. The United Nations, mentioned in the press as a possibility, was out of the question: “My views are far too strongly held for that.” Her Methodist roots would make her abhor sulking and wasting time in self-pity, but they would also act as a brake on “the commercialization of statecraft.” “We’re very mindful of Reagan’s bitter Japanese experience,” says Christine Wall of the scandal the former president created when it was discovered that he and Nancy had accepted $2 million from a Japanese media company for appearances there.

The next step was to assemble her legions of powerful friends to help launch her again. The powerful friends eagerly offered their help and then waited. And waited.

“She could have put together a blue-ribbon panel of British businesspeople who would have helped her organize her office, get a staff, and get it all done,” says Charles Price, former U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom. “There were plenty of dynamic people around to help.” Not only did Thatcher not accept her wealthy friends’ offers of contacts and staff, she never got back to them. Several suspect they know the reason. “She has put all her affairs in the hands of her son, Mark Thatcher,” says a British tycoon, “and a lot of people don’t like Mark Thatcher; he’s very stubborn and thinks he knows everything. We know he’s wrong, but who the hell is going to mix in? Everyone is scared to death to confront her about it.”

“Some people have tried to do so,” according to Price, “first questioning the wisdom of a foundation and then of having family members involved. It kind of goes into thin air.”

“If she fades out, his stature diminishes, and he has no sensitivity professionally or personally,” says a former aide. “Nobody advising her day-to-day has the expertise to help her—it’s an enormous waste. She needs a manager very badly.” It never occurred to anyone, for example, to computerize the 65,000 names from the letters of condolence as a mailing list of potential donors for the Thatcher Foundation.

One story making the rounds in London recently was that Mark Thatcher enjoys referring to President Bush as “George.” But all his adult life he has given those who know him the impression he is very much in a hurry to make it big and more than willing to trade off his mother’s name to do so. “He’s for use,” says a powerful member of the Texas establishment. “The word is, if you want to use him, you can use him.” Mark himself once said, “I suppose I was the slowest learner in the family, the last to realize that because of Mum’s success everyone would have their eyes that much closer on me, their expectations that much higher.” Today if you want to get to Mrs. Thatcher, one way or the other you must go through Mark. He is her adored child, the light of her life. But to most of those outside the family who are close to Mrs. Thatcher, he is known as “that dreadful son.”

“The son is a fly in the ointment,” agrees famed literary agent Irving Lazar. Lazar says he offered to advise Mrs. Thatcher on her memoirs “even if I wasn’t the agent,” but never got to meet her. “The son thinks he can be the agent,” Lazar says. “He’s decided he knows all about publishing, and he’s an amateur. He overestimates the value of the book, and what’s worse, when he had the chance to strike, he didn’t.”

After a dose of arrogance and delaying tactics, a number of U.S. publishers are already cooling to the book. A group of prominent agents were invited to London to meet Mrs. Thatcher, but were told that in order to qualify they would first have to fill out an elaborate questionnaire regarding their qualifications. Then, just before they were due to leave, the trip was abruptly canceled.

“We are not dashing into the memoirs,” says Mrs. Thatcher briskly. “We’re making quite certain the memoirs will be a vigorous intellectual historical record of what we did and what happened.”

“What she doesn’t realize,” counters Lazar, “is that there’s a hot moment when you can get a lot of money. When publishers have time to reflect that Americans don’t understand the basic system of politics in Britain, she won’t get as much. She turned Britain around and made it far more influential in the world. She won the hearts of the world. But what’s happening now is that a lot of her glamour is being dissipated.”

Apparently, the foundation is not much farther along than the memoirs. It must not be viewed as any sort of clearinghouse for her political ideas, lest the British Charity Commission, which is very strict in these matters, rule against giving it tax-exempt status. Nonetheless, the foundation has already hit a snag in England with those who worry that raising money for it would siphon off funds from the coffers of the Conservative Party just when it will need them to mount another election campaign. On the American side Charles Price raises the same questions, saying Mrs. Thatcher’s foundation will be in direct competition with “a number of think tanks.”

“We’ve got to raise in excess of $20 million,” says Lord McAlpine, the head of the board of trustees, who dismisses such doubts. “I was treasurer of the Conservative Party for sixteen years. The last thing I want to do is anything that will harm the party’s chances.” Mark Thatcher has told rich Texans he hopes to raise “$20 million a year for the next five years” for the foundation, although no one can recall being asked to make a donation.

While she waits for her new life to take shape, Mrs. Thatcher, who has avoided the back benches of the House of Commons, still makes her regular rounds in Finchley, the modest district north of London filled with the elderly, people she has known and represented since 1959, a safe haven that will not be easy to give up if she moves to the House of Lords as expected. Her small staff in Finchley tries vainly to keep her schedule full. “If she has a program of three things to do for the day, she’s noticeably looking for other things to do,” says her Finchley representative, Mike Love. “The one lesson you learn in writing a program for her is that you never put on it ‘free time’ or the word ‘rest.’ ”

Mrs. Thatcher admits that several months is not enough time to rebuild a life, but in true Thatcherite fashion she is gamely making the attempt: “You have to create a new pane of glass—we are building up new habits.” One of those habits—and the best way to keep the glamour alive, of course—is to travel to the United States, where the money and adulation that are so lacking at home are plentiful. America and Maggie Thatcher is the story of milk and honey meeting iron and silk. Certainly at the $2,500-a-plate March of the Glittering Mummies that was Ronald Reagan’s eightieth-birthday party in Beverly Hills last February, Mrs. Thatcher was the superstar—even when it was difficult to see who came through the metal detector first, Ricardo Montalban or Cesar Romero, Phyllis or Barry Diller, Dinah Shore or Ed Meese, Rupert Murdoch or Eva Gabor, and, dead last, Elizabeth Taylor, all cleavage and curls with her latest thirtyish escort in tow. Not to mention Nancy Reagan herself, the photo ops with Merv Griffin and Dan Quayle, listening to Liza Minelli sing “New York, New York” to a bunch of people who despise New York, and watching Ronald Reagan lean over to blow out his candles and get frosting smeared all over his tux—well, it certainly beat getting slagged off by Neil Kinnock. And Mrs. Thatcher, sparkling in gold brocade and black velvet, did get the longest standing ovation of the night. That ought to be worth something in future donations to the Thatcher Foundation.

But the next morning the world, and her diminished status in it, intruded rudely. What was supposed to have been a carefree breakfast with the vice president in Century City became a full-scale news conference when word arrived that terrorists had fired three mortar rounds at the British Cabinet meeting being held at 10 Downing Street. Mrs. Thatcher, dressed in a navy suit with brass buttons that looked like a military uniform, was ready with a statement, handwritten on a scrap of paper. She then found herself in the ludicrously unnatural position of ceding control of the event to Dan Quayle and watching him grope with reporters’ questions. There were moments when she actually rocked up on her toes, clenched her fists, and bit her lip as if to silence herself. Finally, a question that implied British and American imperialism was the cause of anti-American sentiment in the Gulf pushed her over the edge. When she was next asked to give her views, she blasted, “I think all comment should be directed to criticism of Saddam Hussein, who started a brutal war on the second of August and has been prosecuting it ever since.” She glared at the offending reporter. “Criticism should be directed towards him, not those who are standing against aggression.”

Once again, she had flattened the opposition. Is that why Americans love her so? Is that why, on Capitol Hill, when tourists see her they break into spontaneous applause? “I don’t know, but I’m eternally gratefully they do,” she says. It certainly didn’t hurt that she was always so breathtakingly well informed, the cerebral half of the heralded Thatcher-Reagan alliance. Reagan might be able to get away with watching The Sound of Music on TV the night before an economic summit instead of reading his briefing book, but Mrs. Thatcher never could nor would.

Margaret Thatcher’s relationship with Ronald Reagan was a cornerstone of eighties geopolitics and a great comfort to them both. Today, out of power, both are symbols of the era of brash acquisitiveness, yet Americans sensed in her the toughness and command of facts that the Gipper was often seen to lack. If Ronald Reagan acted on political instinct, Margaret Thatcher was able to provide the intellectual rationale. “We shared the same views and were fighting to get them accepted,” she says. “Don’t forget, we had to fight to get them accepted.”

“Reagan was particularly appreciative of having Thatcher in his corner during his early ventures onto the world stage, when his inner confidence may not quite have matched his fortress of convictions,” writes Lou Cannon in his definitive new political biography, President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime. “She was quite good at reinforcing him when he needed it, and made a point of giving him credit for something he hadn’t said,” agrees former national-security adviser Robert McFarlane. “She was truly conscious of his limitations, but she adored his constancy—they both understood the power that derives from constancy.” Margaret Thatcher was also masterful at having her way with the president. “I wouldn’t say she exploited him,” says McFarlane, “but she knows how to play upon his lack of knowledge and his chivalrous nature. To be in a room with her really stirrrrrs you,” McFarlane adds. “She is a performer, an overwhelming presence. I couldn’t be around her without just feeling … passion is the wrong word, I guess. She could move men and she knew it. Oh yes!”

Denis Thatcher had a more succinct explanation: “With Ronald Reagan,” he told an American friend, “it takes a while for the penny to drop.” Yet even when they knew they were being had, the Yanks couldn’t seem to get enough of her. Both Charles Price and Robert McFarlane remember the Christmastime visit in 1983 when Margaret Thatcher was flying to Washington from the Far East. After landing at Hickam Air Force Base near Pearl Harbor in the middle of the night, she announced she wanted to visit the battle site. Of course, said the meet-and-greets, they’d get her a car. “That won’t be necessary,” she replied, fishing a flashlight out of her purse and setting off on foot.

Hours later, at Camp David, she had Star Wars on her mind. “Her real purpose was to rein Reagan in before he did serious damage to the alliance—the Europeans were very alarmed by S.D.I.,” says McFarlane. “She and two aides sat across the table from the whole array of the top people in the administration,” says Price. ” ‘Look here, Ron,’ she said. ‘I think we may face considerable turmoil in the alliance.… I think you should make a statement today.’ ” Mrs. Thatcher dived into her handbag once again. “I brought one.” With minor tinkerings, says McFarlane, this was the communiqué that was issued shortly afterward.

She and George Bush were old friends by the time, years later, the president presented Margaret Thatcher with “the Handbag Award” at a State Department lunch. There is no doubt she always wanted Bush to go all the way. Richard Fisher, a Dallas investment banker who befriended Denis and Mark Thatcher in the mid-1980s and had been for a time an aide to Treasury Secretary Michael Blumenthal in the Carter administration, had several private lunches and dinners with the prime minister during that election cycle. She once delivered to him a blistering lecture on the importance of loyalty. “You cannot succeed in politics unless you are loyal to those who got you there,” he remembers her saying. “This is George’s greatest attribute—he has been loyal to Ron.” She had sized up Dukakis quickly. “This Dukakis fellow is a lightweight, an absolute lightweight,” she said, “a lightweight with delusions of grandeur. This is a dangerous combination.”

A few months later when Fisher saw her again, on the eve of the Republican convention, Margaret Thatcher was most concerned about whom George Bush would choose as a running mate. “I would like to see him pick Colin Powell,” Mrs. Thatcher said of the general who had yet to become chairman of the Joint Chiefs. “It would be a bold and high risk. I wish George would do something of this nature and just say, ‘Right, I’ll make it work.’ ”

But by the time George Bush assumed office in January of 1989, Margaret Thatcher had, in the words of a senior American official present at the meetings between the two, “lost the ability to listen.” She lectured Deputy Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger for twenty minutes at a time “and didn’t even seem to hear his answers.” At a meeting in Colorado in 1989, when Bush tried to engage her in a political bull session, she answered him “as if she were turning on a cassette tape.” She was asked to try to relax and she did somewhat, eventually, but by then the Americans, while ever respecting her intellect, generally considered her “difficult and imperial.” (“She always talks too much when she’s nervous,” explains a friend.) Nevertheless, Margaret Thatcher is widely viewed to have bolstered George Bush’s resolve to send troops to the Gulf, since the two of them happened to be in Aspen together when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and she was also in the Oval Office when Cheney called to tell the president that King Fahd would allow American troops on Saudi Arabian soil.

At the Medal of Freedom ceremony, Bush himself alluded to Thatcher’s help on that score and her lack of self-doubt. He remembered telephoning her early on in the Gulf crisis to say that he was planning to allow a single Iraqi vessel through the naval blockade the allies had imposed. She “agreed with the decision, but then added these words of caution—words that guided me through the Gulf crisis. Words I’ll never forget as long as I’m alive,” said the president. “ ‘Remember, George,’ she said, ‘this is no time to go wobbly.’ ”

When she herself was thrown off-balance, Margaret Thatcher turned to the person she has always trusted most in the world, her husband. After the first unsuccessful vote for party leadership was taken last November, Mrs. Thatcher, in Paris for a summit on European security, said she would run on the second ballot. Once home, however, she discussed her plight with Denis. “He said he thought it would be better if I did not stand again,” she says. “It relieved my mind in a way because that was the decision I came to.” Actually, says a friend, Denis had told him two years earlier that “he’d had it—the best thing about being prime minister was going to Chequers.”

‘If you want any help, you ask for it at home. If you’ve got any problems, you take them home. That’s what family life is about.” Mrs. Thatcher sat up straight and stressed every consonant. “It is the home always to be there—always certain that you can find there, no matter what happens, affection and loyalty.… Home is where you come to when you have nothing better to do.

“Denis is absolutely marvelous,” she went on. “We are a very close-knit family.” In addition to the Thatcher’s thirty-seven-year-old twins, Mark and Carol, there’s Mark’s congenial wife, Diane—a former Kappa Kappa Gamma at Southern Methodist University and the daughter of a car dealer—and their two-year-old son. Carol, a freelance writer and, friends say, the one with the sense of humor, has stayed in the background, while her mother has put Mark in charge of everything and found solace with the affable Sir Denis. Now seventy-six, he is “the mainstay of my life,” says Mrs. Thatcher, and, according to Lord Hesketh, “the bedrock on which the whole cathedral sits.”

“She is this extraordinary combination of world-historic figure and common-garden housewife,” says her former staffer and National Review editor John O’Sullivan. “She could change in a second flat from being Queen Victoria, Queen Elizabeth, Attila the Hun, or Genghis Khan to being a 1950s wife,” agrees one of her former ministers. Three years ago after the Trooping of the Color on the Queen’s birthday, Richard Fisher remembers, he went to the private quarters at No. 10 to find “Margaret Thatcher down on her hands and knees packing her own bag, and there’s Denis mixing a salad with his hands in the pantry.” Lord McAlpine says, “The dynamic of their relationship is simple: it’s just love, true affection, romance—they love each other. He’s enormously protective of her.”

When asked to speak in personal terms about Denis, however, Mrs. Thatcher fielded the question with English reserve. “Denis is on several boards, which he is extremely conscientious about—all the board papers are thoroughly analyzed before he ever goes to board meetings. He’s run the family business. He knows what it’s like when you are committing your own money.… He’s a crack accountant and he also always has been mad keen on certain sports and living up to certain standards in those sports.” Golf, she said, which Sir Denis plays with left-handed women’s clubs, is his favorite. “He’s very, very pro golf,” she said in her best instructional tone, “because when it comes to playing professional golf, the standards of the golf are some of the highest standards in sports. There are no histrionics.”

Denis has been celebrated in British pop culture through the play Anyone for Denis?, in which he is “mad keen” on golf chiefly for the libations of the nineteenth hole, and in the hilarious “Dear Bill” letters in Private Eye, in which an old buffer never far from gin meltdown partakes in and reports on a daffy right-wing world.

In fact, such a cover of buffoonery serves him well. Denis Thatcher is far right in his views—he has always been an avid advocate of trade with South Africa and has called the BBC “a viper’s nest” of “outrageous bloody pinkos.” (A female dinner partner remembers him referring to Indians as “wogs.”) “He played the fall man and he was ridiculed,” says Fisher. “That was fine—that was his role.” But during his wife’s tenure, Denis, like his son, also had the propriety of several of his business dealings questioned.

For many years Denis was a consultant for a building group called I.D.C.—he spent six to seven days a month working for the group, which is involved in civil engineering. His most controversial intervention on the firm’s behalf came to light when his letter to the government’s secretary of state for Wales—about delays in building permits on an I.D.C. project—was published in the British press in 1981. The message from Denis Thatcher, on 10 Downing Street notepaper, prompted the secretary to scrawl to his staff in the margin, “The explanation had better be good and quick.”

Also in 1981, Denis and Mark Thatcher got embroiled in a controversial building contract in Oman. Mrs. Thatcher was making an official visit there during the same time that a British construction company, Cementation International, was bidding on a billion-dollar university complex. Mark, who was working as a consultant for Cementation, showed up as well. Mrs. Thatcher lobbied on behalf of the company, and after it won the contract, Mark reaped a sizable fee. For his part, Denis Thatcher was chairman of a company that had a 50 percent interest in a bid to subcontract to Cementation. After The Observer broke the story in 1984, Mrs. Thatcher and her government were criticized in Parliament for the striking conflict of interest. Later The Sunday Times revealed that Denis was a co-signatory on the bank account in which Mark’s fee was deposited.

These days, Denis, who spends one week out of four in the U.S., is in business with some heavily investigated characters. One of his major ventures—he serves as deputy chairman—is with Attwoods, a British waste-management concern. Municipal garbage contracts and landfills in high-growth areas like Florida are a lucrative business, and a substantial portion of Attwoods’ profit comes from an American subsidiary, Industrial Waste Services in Miami. When Attwoods acquired I.W.S. in 1984, it was owned by Jack R. Casagrande and Ralph Velocci and some of their relatives; as part of the sale, these relatives received Attwoods stock, and Casagrande and Velocci have joined Denis Thatcher on the Attwoods board. Casagrande and Velocci come from three generations involved in the garbage trade in New Jersey and New York, where another company Casagrande has an interest in was charged with price-fixing and illegal property-rights schemes. A 1986 report from Maurice Hinchey, chairman of the New York State Assembly Environmental Conservation Committee, stated that organized crime is “a dominating presence” in the state’s garbage industry.

“One of the great advantages for I.W.S. was to be subsumed under a British corporation which had the luster of the Thatcher name,” says Alan Block, a professor at Pennsylvania State University and the author of a book on organized crime’s ties to the waste industry. F.B.I. reports refer to I.W.S.’s business dealings with convicted mob associate Mel Cooper, now serving twenty-five years in prison for racketeering. Cooper ran a garbage-equipment leasing operation in New York that was alleged to be a front for loan-sharking operations connected to the Gambino, Genovese, and Colombo crime families.

In 1986, I.W.S. was convicted in Florida of conspiracy in a criminal anti-trust case and fined $375,000. Also that year, Casagrande and Velocci were investigated, but not indicted, in an alleged bribe of the mayor of Opa-Locka, Florida, for that city’s garbage contract. In 1987, a civil suit was brought against I.W.S. and Casagrande and several other defendants for allegedly defrauding Marion County, Florida, in a garbage-conversion scheme. Casagrande was also charged with grand theft and conspiracy. Earlier this year, I.W.S. and Casagrande were part of a $2.3 million out-of-court settlement.

While Margaret Thatcher was prime minister, unofficial Downing Street and Attwoods sources would reportedly dismiss any news accounts of the company’s activities by asking the rhetorical question “Do you think British intelligence would allow Denis Thatcher to take a job that could be linked to the Mafia?” Hinchey claims that Scotland Yard, at least, did inquire about Attwoods and I.W.S. “I’ve seen documents from British authorities,” he says. “They knew about these things and were frustrated about it.” Yet British authorities apparently did not contact others who could have aided them. Says Robert Waters, at the time an assistant state attorney in Florida’s Organized Crime and Public Corruption Unit, “I was the one conducting the bribery investigation, and nobody from the British government ever contacted me or any of the detectives.”

By all accounts, Denis has never questioned his own authority. “In his own house he would have the last word,” says Lord McAlpine. “It is a conventional relationship.” But the paradox exists that, despite his being an apparent male chauvinist, it was Denis’s money, gotten from the family chemical-and-paint business (he once wrote a book called Accounting and Costing in the Paint Industry), that allowed his wife to pursue a political career. “He has always seemed dazzled by—and devoted to—her,” says Lord Gowrie, Thatcher’s minister of the arts, who is now chairman of Sotheby’s U.K. But Denis, though fiercely protective of his wife, has also injected a note of reality. Gowrie recalls an after-dinner speech she once made at the Imperial War Museum in the flush of victory after the Falklands War. Afterward she asked, “Dear, was I too long?” “Bit,” he replied.

If Denis has successfully deflected criticism of his business transgressions, his son has not been as fortunate. In fact, almost nobody has a very kind word for Mark Thatcher. “Mark gets a bit of a bum rap,” says John O’Sullivan, the National Review editor. “He doesn’t have immense charm. He’s not winning.” Indeed. He’s the son who mixes with internationals arms traders; the wheeler-dealer, suddenly wealthy son who travels with a butler and, last fall, bought a $3.5 million London town house with up-to-the-minute heavy security; the inept son who got lost in the desert for six days on the Paris-to-Dakar rally when he wanted to be a racecar driver, causing his mother her first public tears (and prompting former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt to comment privately, “It’s the first time I ever realized she was a woman”); the arrogant son who got his mother in hot water over the Oman deal and who has more recently clumsily hinted that certain people haven’t done enough to support the foundation she wants to set up; the boorish son who used to pull out a walkie-talkie in the middle of dinner parties to talk to his bodyguards; the snobbish son who told the cultivated billionaire Walter Annenberg that he was setting his table with the wrong glasses for red wine and that his golf course was “Mickey Mouse.”

“He’s not the brightest guy in the world,” says columnist Nigel Dempster, “and clearly what he’s done smells a little.” That son. “I think Mark is extremely bright and loyal to his mother,” says Richard Fisher, a Mark defender. “I think he realizes that great people can serve and then be forgotten and their offspring amount to nothing. The Churchills basically live in poverty by Texas standards. He will take good care of his mother.” Recently when Fisher hosted eighteen for dinner in Mrs. Thatcher’s honor in Dallas, he toasted her “as a wife and mother first, then as the greatest prime minister since Churchill.” “Richard,” she replied, ” you have finally gotten your priorities right.”

“I see something else,” Fisher continues. “I think she’s a loving mother, and, if anything, there is a sense of loss that in her career she didn’t spend enough time with her children. I wouldn’t call it guilt, but she works very hard to love her two kids.”

When asked directly about Mark’s role in her life today, Mrs. Thatcher was not at all pleased. “He is helping make some of the arrangements, and he is a very, very good businessman. He’s a born businessman, as indeed my husband was. He built up his own business and he managed to sell part of his interest in it.” When pressed about just what sort of business he was in, she reluctantly answered, “It’s a big concern for security—the best possible kind of home-security systems.” Asked about his qualifications to handle her affairs now, she lost her patience. “Look, my children are not children anymore,” she said. “They know about life. I find he is one of the most businesslike people I deal with. You want something done, he does it quickly—there’s no ‘Oh, well, I’ll do it tomorrow.’ ”

Despite the perception of many loyalists that the foundation is a “nonstarter,” McAlpine confidently predicts “we’ll be quite active by the end of summer.” Mrs. Thatcher herself says, “The foundation has to operate in Britain, America, and in Japan. There are people the world over who think the way we do.”

Apparently so. The day after she received the Medal of Freedom, Thatcher was introduced by Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan to members of five right-wing think tanks at the posh Four Seasons Hotel in Washington. She delivered (gratis) a rousing forty-five-minute address on Europe and advocated the economic equivalent of nato. Imagine crossing the TelePrompTer technique of Reagan with her brains—for these thirsty hard-liners her words went down like vintage champagne. Anyone who had thought she might modify her views on opposing a common European currency or a European Superstate as a result of her downfall would have been deeply disappointed. “Utopian aspirations,” she informed her rapt audience of right-wing stars, “have never made for a stable policy.”

Her next stop, Dallas, seemed more of a favor to Mark, who made sure she was wined and dined by the civic elite. At one dinner, she took issue with the C.E.O. of The Dallas Morning News, who, in a discussion about social inequities, dared to mention the notion of class structure. “Any reference to class distinctions is a Marxist concept,” Thatcher told him. Although she was now able to command a cool $60,000 per speech—$20,000 more than Henry Kissinger gets—she made yet another speech for free to a room full of wowed million- and billionaires. During the question-and-answer period following, she referred to the special relationship between Britain and the United States: if it ever faltered, she promised in jest, “I may come back.”

Finally, though, it was the plight of the Kurds that led Mrs. Thatcher to abandon her stance of official reticence. “The people need help, and they need it now,” she admonished on April 3, while President Bush was on vacation in Florida and John Major was glimpsed at a soccer match. “It is not a question of standing on legal niceties.… Supposing they were your children, wouldn’t you want to help?” Major’s announcement of emergency aid to the Kurds followed three hours later, but his aides angrily rejected the suggestion that Mrs. Thatcher was in any way responsible. “It is time some of the elderly loose cannons on the deck were pitched overboard and shut up,” one senior minister reportedly snapped.

A week later, when she returned to New York to open the newly remodeled British Airways terminal at J.F.K. airport, Mrs. Thatcher also dropped by the United Nations and had a “very lively ding-dong” about the Kurds and the Gulf with Javier Pérez de Cuéllar and other U.N. heavies.

“She’s invigorated, in very good form,” says John O’Sullivan, but “she wishes she were in office.” And yet, he says, “when she was in power there were always constraints—she couldn’t develop a positive agenda. With the reception she received from the Washington speech, she realized she could be this new world figure—a female Kissinger,” he enthuses. “There are still remnants of official caution, but I could see her shaking it off. In another six months, she’ll be unrecognizable. She’ll get more outspoken.”

That’s just what many Conservatives in Britain fear most. Already Major’s government has begun to dismantle the poll tax and increase child benefits. That old consensus is rearing its equitable head. For Margaret Thatcher that’s roughly the equivalent of making Jesse Jackson the head of the Ku Klux Klan. Already, it is said, she has taken to calling Major’s government “the B team.”

Reports are now circulating that, in addition to a visit with Gorbachev in May, she will make a triumphant appearance—as a sort of Britannia-on-a-chariot symbol—at next year’s Republican convention. “There’s no shortage of people who would love to entertain her,” says her close friend and former minister Cecil Parkinson. “But that’s not a career, is it?”

“She’s going through a period of enormous boredom,” says Lord Hesketh. Nevertheless, loyalists like Hesketh maintain, one must never count Margaret Thatcher out. “She was destroyed by the poll tax and her views on Europe. The chattering classes—the media, the dons, the Pinters—they all hate her, they loathe her. They are unable to have serious thoughts about what she’s done, what she’s achieved. They’re absolutely blinded by their hatred. Because they don’t like her they say she’s gone. Exit, stage right. That’s a great advantage to her.”

“If she aspires to be an influence in British politics, and I think she does,” says Robert McFarlane, “there is a need for a pause. If she’ll just tap her foot for a while, they’ll come her way. They’ll realize what a giant she is.”

“My role now is to go round the world saying, propounding, what I believe in, and to help those reaching out to democracy,” Mrs. Thatcher declares. In the U.S., she’s already got millions on her side. Deep in Orange County, the denizens are still talking about the penetrating speech they recently heard from her. “After all,” said one matron, “she is the most powerful woman who ever lived.”

For Margaret Thatcher, at least there’ll always be an America.

No Comments