Original Publication: Rolling Stone, July 23, 1981

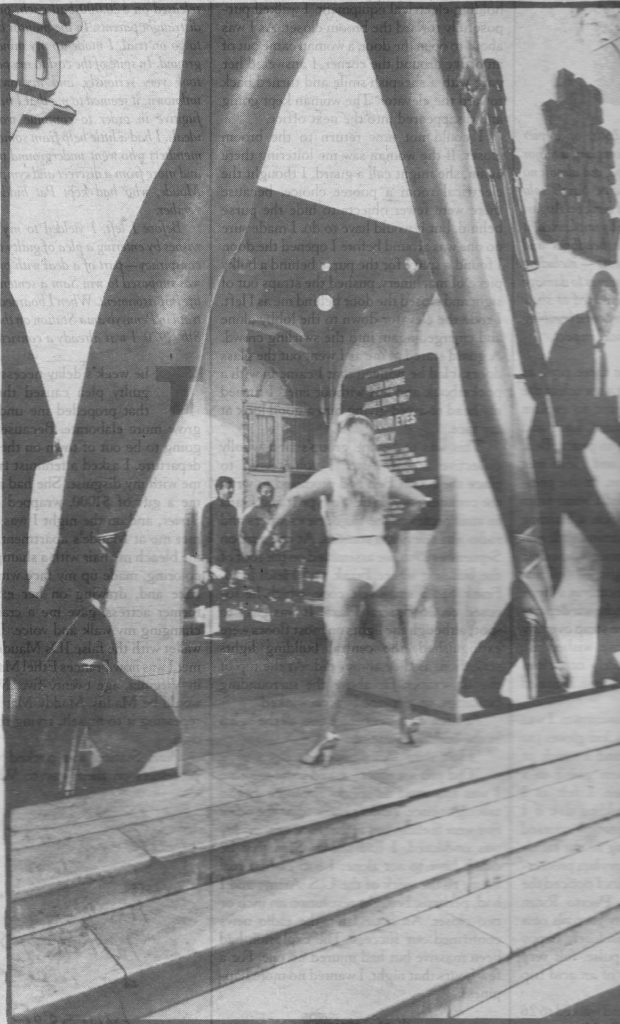

Almost every year, Edy Williams comes to Cannes to strip: on the roofs of cars, at the beach, in front of the wedding-cake architecture of the Carlton-Hotel, the unofficial headquarters of the thirty-fourth Cannes International Film Festival. Prominently featured onscreen just twice – in ex-husband Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and Supervixens – she is an annual happening, a forever starlet at least as old as the festival itself. To a mocking crowd, she bares her greased-up breasts sprayed with gold glitter, her generous, wobbly bottom, and sticks a finger down her leopard-print bikini in a futile effort to scratch below the gaudy surface of world cinema. “Ed-die! Ed-die!” cry the paparazzi in accented English. “Turn your behind to here. That’s it. Oh, Ed-die, take it down!”

Edy Williams has chose to pose right under the cutout legs of a huge display announcing the latest James Bond movie: two long stems in spiked heels that spill out of a bikini and form an Eiffel Tower of sorts over the entrance to the Carlton. Thus, if you want to get to the crowded action inside the lobby, you must pass under this vulgar arch, which becomes indelibly imprinted on everyone’s consciousness for the duration of the festival. Edy Williams, however, is not so lucky. The aging vixen may uncover herself generously here, but she is never discovered. Cannes is primarily a marketplace, and old merchandise, no matter how it’s recut and reedited, frays along the edges of the dealmakers’ minds. Finally, a grizzled beggar in the crowd can take no more. He begins to shout: “Le cinéma est malade!” – “The movies are sick!”

Edy Williams, the Cannes Film Festival and the movie business are not dissimilar in 1981. They are all over the hill, but they don’t quite know what to do about it or how to proceed. In the early years of the festival, Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau used to watch the premiéres of movies like La Dolce Vita in the same audience with Luis Buñuel, and producers used to anchor brightly lit warships in the harbor or parade camels down Cannes’ main drag, the Croisette, to announce their latest epics. This year, a couple of prop planes flew around announcing Superman III, and the first thing hitting anyone inside the Carlton were garish, four-sided displays that announced: “Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Cinema Department presents its first production, produced by the Administrative Committee for Revolutionary Information and Moral Guidance Branch: The Battle of Tagrift.”

“This is a rain-check year,” said British critic Alexander Walker, a Cannes veteran. “There is a great shortage of good films, and the character of Cannes has changed immensely. You used to be able to tell what was going on inside a society by looking at its films. This year, there’s an absence of character. There’s a product called film, which is not an indication of what a producer thinks is mass consumer entertainment suitable for pay TV, satellites and airplanes. The global village has produced a great ironing out of originality.”

It takes several days merely to unravel the myriad layers of Cannes, which is simultaneously the world’s most prestigious film festival and a teeming marketplace for independent producers – a place where movies are bought, sold, dreamed up and dumped. This year, for example, a film based on a Mario Puzo story that couldn’t be sold two years ago as Seven Graves for Rogan was back, recut as A Time to Die. Movies took on entirely new story lines as they were dubbed from one language into another.

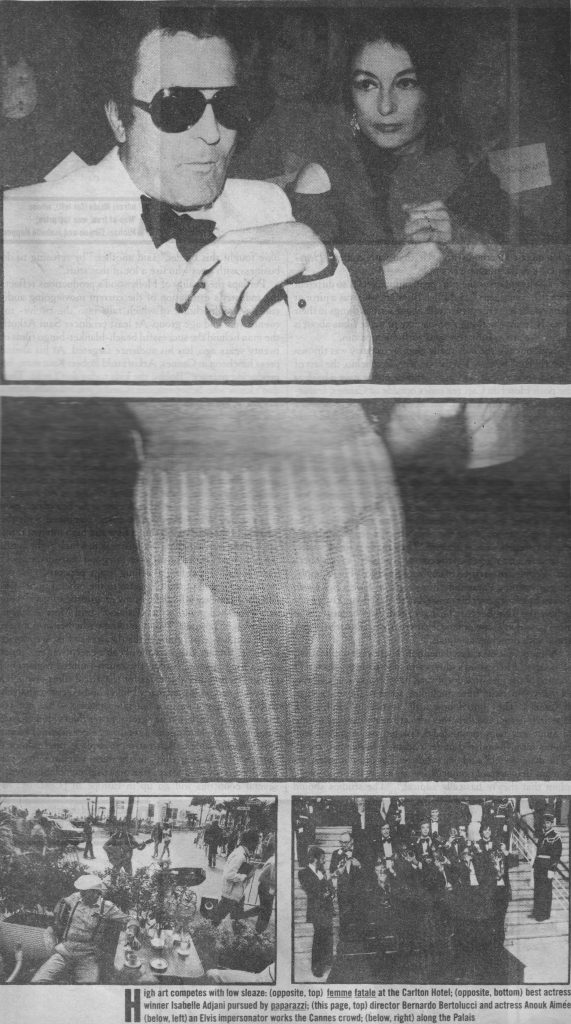

Dozens of countries screen their product in the “market” – both in the four-story Palais des Festival and in theaters off the Croisette. In the Palais, a big bazaar of cinemabilia where films both in and out of competition are shown, the newest swivel theater chairs were up for sale, along with the latest in porn posters. In Cannes, high art and low sleaze constantly compete for attention, but the sleaze-meisters far outnumber the artistes.

The entire fourth level of the Palais is given over to the fourth estate – the thousand or so film critics, reporters, photographers and TV crews who come from around the world to await “major announcements.” Industry traders like Variety, the Hollywood Reporter and the British Screen International tend to cover Cannes the way Stars and Stripes covers a war.

For Hollywood, however, this was the year that wasn’t. This was the year the majors came to Cannes mostly as a hedge against having no films to distribute next year – the result of slow business and an impending directors’ strike. The studios were there to pick up the kinds of low-budget indie cheapies, particularly for foreign markets, they would not have gone near for a few years.

The American prescence was definitely subdued. The businessmen were distracted by an elaborate game of executive musical chairs – United Artists’ sale to MGM, Fox’ new ownership by oil man Marvin Davis, Filmways refinancing itself, etc. – and stars were in short supply. During the first week of the festival, Jessica Lange and her new baby were practically the only subject for the paparazzi, until they got bored and started taking pictures of each other. Jack Nicholson was an elusive figure in a white suit seen mostly at night: behind the windows of a limosine crawling up the Croisette, through the glass at Felix’ restaurant dining with director Bob Rafelson and Lange, or sitting on the steps of the Palais while The Postman Always Rings Twice played inside.

The American entries at Cannes were a large disappointment. Thief and Heaven’s Gate, which were shown in competition, and The Postman Always Rings Twice, Honeysuckle Rose and This is Elvis, which were shown outside of competition, had already opened in the U.S. to disastrous or mediocre business. And, with the exception of Thief and This is Elvis, a few decent reviews. The one American film that did cause a stir was Polyester, filmed in Odorama and starring the ultimate female impersonator, Divine. At least it had movie junkies scratching and sniffing happily into the night.

“The caliber of films and the people making them has declined over the last few years,” said Sandy Lieberson, a vice-president of the Ladd Company and one-time president of Twentieth Century-Fox. “Filmmakers today seem so much more concerned with style than with content. Heaven’s Gate is the ultimate example.”

“The intention of the European filmmakers is so different from the Americans,” said Ellen Burstyn, who was a juror at Cannes. “At least they try to talk about serious things in their films. It seems the thing we most like to make films about is crime. We are awfully frivolous with the medium.”

Symbolically, the only really glamorous party was thrown “just for fun” by pay-TV tycoon Jerry Perenchio, the last of the old-style moguls at Cannes this year. He gave a bash at the poshy Hotel du Cap, ten miles outside of Cannes, featuring caviar by the kilo, Dom Perignon, by the bucket, a smashing fireworks display and Peter Allen, who had been flown there via Concorde to perform for the Hollywood hot-shots in attendance – many of whom seemed somewhat baffled by Allen’s flamboyant energy.

You didn’t see any of the Hollywood studios throwing away their money around like that. In the wake of the disappointing American films at Cannes, a complex of reasons was generated to explain the current crop of mediocrity: obviously there are more dealmakers than filmmakers. The usual explanations about the abdication of studio authority and selfishness were reiterated. They made a lot of sense. “Executives have given up the role of producer,” says Lieberson. “People are terrified of confrontation now. For example, the guy running Paramount hires a guy to have a fight with Steven Spielberg over his movie, but the hired guy knows not to have the fight because he’ll get fired. And because these hired guys don’t have practical experience in films, they can’t argue with directors as equals.”

A few people even dared mention, but not for publication, of course, Hollywood’s dirty and not-so-little secret of cocaine abuse and how deeply and how obviously it’s affected many American films, including some of those screened at Cannes. They noted how little anyone in Hollywood, especially actors and directors who are heavy users, is willing to admit how many misguided decisions have been made and careers have floundered under cocaine’s misleading thrall. “The drug is evil,” said one producer, “because it gives you so many delusions of grandeur. But try to get these people to admit that they’re basically addicts.” “The studios should have fought this harder,” said another, “by refusing to do business with guys who use a lot of that stuff.”

Perhaps the quality of Hollywood’s productions reflects the industry’s estimation of the current moviegoing audience, a sizable chunk of which falls into the twelve- to-twenty-year-old age group. At least producer Sam Arkoff, the man behind the successful beach-blanket-bingo films of twenty years ago, has his audienced targeted. At his annual press lunch in Cannes, Arkoff told Robert Kaufman, his producing partner, “Bobby, the kids today don’t read. They don’t know who Schopenhauer is, and if you tell them there’s trouble in Venezuela, they’ll say ‘Whadda ya mean? He just pitched his fifth straight shutout.”

If Arkoff was right, the old beggar was certainly right as well. The movies are sick, particularly American ones, and every American film executive at Cannes could recite the statistics by heart: U.S. box office is down by at least fifteen percent from last year, and the cost of making a movie has risen to the point where theatrical release is no longer a guarantee that a movie will break even at the box office, even if it’s a hit. Why? Production costs, combined with the soaring expense of marketing a film and high interest rates, are forcing moviemaking – a business in which eight out of ten films never turn a profit, even in a good year – to be about as financially rewarding as selling soggy popcorn.

From one end of the Croisette to the other, Cannes was filled with uneasy talk and gloomy prognostications. “We’re at a watershed point in this business,” said Merv Adelson, chairman of Lorimar. “We don’t know whether or not next week’s audience will come to the theaters or first see movies on cable. In fact, the presence of cable executives at Cannes cast a long shadow. So far, the much-vaunted bonanza of video cassette and cable sales for theatrical films –which a few years ago prompted many Hollywood executives naively to believe they were in a fail-safe business – has not yet materialized. “Inflation has grown faster than videocassete sales,” said Michael Fuchs, a senior vice-president of Home Box Office. Cable still threatens to explode the traditional pattern of releasing films in theaters: satellites that can simultaneously broadcast a film in two different languages to several countries will go up in Europe in 1984. And the majors are concerned too that the easy pirating of such signals will affect their ability to collect licensing fees.

The uncertain future wrought by pay TV is also the main issue in the strikes that have been crippling Hollywood. Significantly, Fuchs said that if Hollywood production declines to sixty percent of what it is today, then HBO itself would have to consider financing the features.

“Last year, Lew Grade held up a picture of the Titanic,” said the Hollywood Reporter’s John Austin. “Evidently, he didn’t raise it high enough.”

If the present demise of Hollywood haunted Cannes, the circus roared on. So what if the pope had been shot on the afternoon the festival began, just before people trooped in to see an Italian movie that dealt with terrorism? At Cannes, it was always show time.

This year’s starlet was Annie Ample, a San Fernando Valley native who reportedly had her twin forty-fours insured by Lloyds of London for $1 million. Annie began her Cannes career by becoming a finalist in the punk costume contest at the premiere of Lorimar’s punk musical, Urgh! A Music War, and parlayed that into contracts for two bit parts – all without a single agent. “The film business is run by old people for young people,” said Urgh! producer Michael White. “But the only thing the guys in the film business are really interested in about that age group is teenage girls.”

One of the veterans who really knows the Cannes circus inside out is Sam Arkoff. As founder of American International Pictures, that repository of top B hits and horrors now viewed as cinematic treasures in film schools and museum retrospectives, Arkoff is the eminence grise of the indies. “I’ve been associated with over 500 productions,” Arkoff said, “and the last place I ever thought I’d wind up was a museum.” Arkoff, who merged AIP with Filmways in 1979, recently sold his Filmways stock and was in Cannes to announce he was back in business – as Arkoff International Pictures.

He is a genuinely nice man who helped launch Francis Coppola, Martin Scorsese and Woody Allen in their careers. There is an integrity to his image that is totally in keeping with his calling. His Cuban cigars probably cost more than his suits – immaculate polyester leisure ensembles with matching white patent leather loafers or baby-blue suede hush puppies. No Gucci for Sam.

No “auteur fecal matter,” as he puts it either. And no big budget Bs. “Arkoff has constantly maintained that the film business has been on a suicide course,” said a press release he issued in Cannes, “that the worst horror stories have been acted out behind the cameras and not in front of them.” The release went on to say that “three of AIP’s most recent successful pictures under the Arkoff regime, Love at First Bite, The Amityville Horror and Dressed to Kill, cost a total of less than $15 million.”

“I told George Litto, the producer of Dressed to Kill, and Brian DePalma, the director, that if they went over budget, they’d have to pay me the difference out of their fees,” said Arkoff. “And they did – a half-million dollars. I understand they didn’t have such controls on their latest film [Blow Out, with John Travolta], and the budget went up to $18 million. It never would have with me, I’ll tell ya.”

Arkoff has Cannes wired. Twenty years ago, he was the first to stay at the manicured and discreet Hotel du Cap, now headquarters for the heaviest hitters of Hollywood but usually filled with the sort of habitués of the south of France who look like they were born before the French Revolution. As Arkoff made his way to lunch at Eden Roc, the hotel’s tony restaurant, he explained what was wrong with Cannes. “Last year, there were too many people here who had no business being here, who took large advances, lost the money and ran. Now, money’s tight, and a lot of people don’t feel like coming.”

An American producer stopped by Arkoff’s table to introduce his wife to Arkoff’s wife, Hilda, a charmer who mothers everyone she meets. “I wanted you two to meet,” the producer said, “because I know you sculpt and my wife collects.”

“Oh,” said Mrs. Arkoff, “how nice. What do you collect?”

“Rodin,” the woman answered.

“Lovely,” said Mrs. Arkoff, “We’ve just bought a Henry Miller.”

“Really,” the woman answered. “We’ve just sold ours.”

A few days later, Arkoff held court at the Carlton terrace. “This is the Tower of Babel,” he said. “Look around: this place is full of scoundrels and cheats. Some of these people don’t even have a place to sleep. But they’ve all got a project. They’ve got a film they want to sell.”

“Hello, Sam. Have a cigar.” The man hovered over Arkoff’s table. “You remember Sam, the last time I offered you a cigar? I was pitching that story.”

“Yeah,” said Arkoff, “the cigar was better than the script.”

The talk the first week of the festival was that a dazing, if not knockout punch, had been dealt to Cannes by the newly created American Film Market, a gathering of 1200 independent producers and foreign sales representatives in Los Angeles, organized by the American independents at Academy Award time to woo business. The AFM unbalanced Cannes, and in light of complaints about Cannes’ “rip-off atmosphere,” caused the festival to institute reforms this year. Next year, a grand new palais, now under construction on the site of an old casino down the Croisette, will be ready, and the festival will take on a whole new atmosphere.

But for now, the French were still the French. They much preferred their dogs to foreigners. On the Carlton terrace, in fact, there was even a special ankle-high Dog’s Bar built into the stucco wall. The most vile French dogs were small and wore barettes, but a large dark mongrel named Remus, who belonged to Robert Benayoun, film critic of the French magazine Le Point, was Cannes’ most famous dog. Benayoun never leaves home without him. “Remus has seen 2500 films,” explained Benayoun, the man who crowned Jerry Lewis auteur of all auteurs. “He prefers the shorter version of Pierrot le Fou; westerns and musicals are his favorites.” Benayoun was definitely distressed that Remus had missed the original long version of Heaven’s Gate, which the critic had caught in New York last fall. At Cannes, Benayoun took it as his personal responsibility to defend Michael Cimino’s directorial honor against the heartless, reactionary U.S. critics. “The Americans cannot accept the fact that the American dream was built on the blood of its immigrants,” Benayoun declared. “Cimino must be revenged.”

There was no escaping Heaven’s Gate at Cannes. Its colossal failure sent tremors through the world film industry. If some European critics saw it as a grand epic, the Americans considered it the scary symbol of everything wrong in the movie business today. It was contantly brought up in conversation. As usual, Sam Arkoff had the best line on it:

“In their day, Harry Cohn and Louis B. Mayer would have said ‘fuck you’ to Michael Cinimo and suspended him. Now you get some namby-pamby people who are essentially money men who don’t know what they’re doing. I mean when the pope wanted Michelangelo to paint the Sistene Chapel,” he said, ‘Mike, I’m gonna give you so many lire to paint the ceiling, and here’s what you’re gonna put in there: I want all the saints. Don’t make em look like Jews, and I don’t want Jesus to look like a Jew either. I want him to be a pretty blond.’ And Mike would use all his abilities to paint what the pope wanted. Mike wouldn’t say, as they do today, ‘Look, pope, I got a Sicilian boyfriend and I want him in.’”

As Cinimo, Kris Kristofferson and Isabell Huppert walked into the Palais on the opening night of Heaven’s Gate’s premiere at Cannes, a hundred paparazzi were crushed together on the steps to photograph the silent trio. “Poor American cinema,” one Frenchman called out. And cleverly swishing into the limelight right behind the stars, her camera crew following her all the way, was horror film queen Carolie Munro, in Cannes to film The Last Horror Movie.

The next morning, at a press session for European TV, Cimino, who steadfastly maintains that he’s never read the American reviews of his movie, was told by United Artists President Norbert Auerbach that the jeers in the theater the night before had been generated by a claque of Americans who had taking it upon themselves to boo the picture.

Ciminio’s behavior at Cannes suggested nothing so much as the film world’s equivalant of the U.S.’s role in Vietnam – a denial of reality and throwing good money after bad. For example, at the press conference – his first on Heaven’s Gate – Cimino was able to recite all the facts and figures surrounding the technology of his epic: what the temperature and wind velocity were on a certain day, the degree at which camera lenses had to be frozen because of the heat, the number of feet off the ground the roller-skating platform had to be constructed. Then he admitted that his meticulously researched work, hightly touted as the re-creation of the Johnson Country cattle war, was not historically accurate – that the slaughter of immigrants by rich Americans, made so much of by European critics as the page noir of American history, in fact never took place. Ciminio refused even to discuss what he thought his film was about. His behavior resembled that of Robert McNamara, the former American secretary of defense, in the early days of Vietnam: he had all the technology down pat, but he could not justify why he was there.

Nevertheless, many foreign critics are still convinced Cimino was forced to mutilate his work. They did not hear him when he flatly stated, “We did not recut the picture for our critics. We pulled it on our own.”

“It’s a pity it was cut as savagely as it was,” said John Hanrahan, entertainment writer for Australia’s Sydney Sun. “I would happily have sat through another half-hour.”

“The first fifteen minutes are fantastic, then the story is not clear,” said a woman from Italian television. “It must be better in the longer version.”

Cimino, whose next project was announced as “something” for $8 million for EMI, told Swiss TV: “My interest is to continue to explore the American experience, the immigrant theme.” The powerful reaction to Heaven’s Gate from American journalists must have occurred “subconsciously,” he said. “It was very disturbing.”

One European UA exec said it cost $300,000 to launch Heaven’s Gate at Cannes; another $180,000 was spent opening the film in France, Belgium and Switzerland. (It closed two weeks later.) Although Ciminio said his film cost $35 million, Auerbach confirmed a figure of $45 million with the comment, “Please, you’re spoiling my lunch.” He then quipped, “You heard, didn’t you, that UA is having Cimino do a sequel to Heaven’s Gate? It’s called Go to Hell.”

The arrogance of the American directors attending Cannes was unmistakable. For example, while generally charming the world press, Thief director Michael Mann basically referred to himself as one of a handful of important American directors – despite the fact that Thief is his first feature film. Bob Rafelson implied that his version of The Postman Always Rings Twice was superior to the original classic starring John Garfield and Lana Turner.

Perhaps he can be excused, because the Postman press conference at Cannes, with Jessica Lange and Jack Nicholson in attendance, was a parody of the National Enquirer man meeting the Cosmo girl. To Jessica Lange: “Do you wear your hair over your eye like that because you want to imitate Veronica Lake?” Rafelson was queried: “What did you wear when you directed the sex scenes?”

Still, with the exception of Thief, most of the U.S. films got better reviews in Europe than at home, but for the first time in many years, not one American film won a prize. Ironically, the most interesting films shown were extremely low-budget by Hollywood standards and either were made under the strictures of state censorship or in what are presumed to be countries with moribund film industries.

From Spain, there was Antonio Gades’ beautifully executed post-flamenco ballet, Blood Wedding, directed by Carlos Saura, and from England came Chariots of Fire, the moving, true story of two of Britain’s heroic runners in the 1924 Olympics. Chariots won the hastily organized First Annual American Critics Prize in a poll taken a few days before the festival ended. Half financed by Fox, the film cost $6 million but looks triple that amount. In the kind of move that’s obviously made Hollywood what it is today, Fox elected not to distribute Chariots in the U.S. – just Europe. Ladd/Warner Brothers has picked it up for U.S. release.

Tow of the finest films were Eastern European. Hungarian Istvan Szabo’s Mephisto, a brilliantly acted portrait of a compromising artist under Hitler, cost $980,000 and looked almost as expensive as Heaven’s Gate. Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Iron, a fictional interpretation of recent Polish political events that incorporates documentary footage of Solidarity, won the Palms d’Or, Cannes’ highest award.

The contrast between the privileged Americans and Wajda was particularly striking. The Polish government was not pleased when he made Man of Marble, the first half of his interpretation of modern Polish political history (it won the International Critics Award at Cannes in 1978). He had begun Man of Iron only eight months ago, and until the film cans were counted at the Nice airport, he thought the Polish authorities had held back one reel. Just before receiving Cannes’ highest award, Wajda quietly said. “The time needs such a film. My ambition was to be the first. If it is a special film, it’s because it is a special moment for Poland.” On awards night, he wore a small Solidarity button.

There have always been allegations that the prizes at Cannes are diminished because the jury is rigged, or at the very least, tilted towards the French. “We’ve always suspected,” said Variety veteran Robert Hawkins, “that the French have a school somewhere in the Alps where they send their jurors to teach them how to get their way.” That suspicion was confirmed with the announcements of the acting awards. Best actress went to France’s sweetheart, Isabelle Adjani, for two overwrought performances – first in Quartet, a mannered, haute monde British-French production of a Jean Rhys novel, and Possession, a stillborn son of Rosemary’s Baby in which Adjani has intercourse with the devil, disguised as a bleeding octopus. Best actor went to Ugo Tognazzi in Bernardo Bertolucci’s incomprehensible The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man, instead of to Klaus Maria Brandaeur in Mephisto, a screen performance many agreed was one of the finest seen in years. But Tognazzi, a very popular actor in France, had competed in Cannes seven times without winning. As a sop, Mephisto received the screenwriting prize.

After two weeks of the frenzy of Cannes, one tended to absorb such information with the barest sense of outrage. The final night’s awards ceremony, for example, became more sublime than ridiculous. The awards night is run by the paparazzi, who inhabit the first four rows of the theater and shout out directions to the stars.

Even more ludicrous were two items in Variety, both dated the last day of the festival. From Cannes, Joann Carelli, Michael Cimino’s longtime companion and producer of Heaven’s Gate, blamed United Artists for the extraordinary costs of the movie, charging that the studio was too lax with her and Cimino. Another item reported that the majority of top-grossing U.S. films to date this year had either been horror films or extremely violent ones. In light of that information, it was particularly interesting to read that UA Classics, the special marketing and video arm of United Artists, was recutting Heaven’s Gate yet another time – for resurrection as The Johnson County Wars. The “new version,” Variety reported, “will excise romantic overtones and concentrate on the more violent action.”

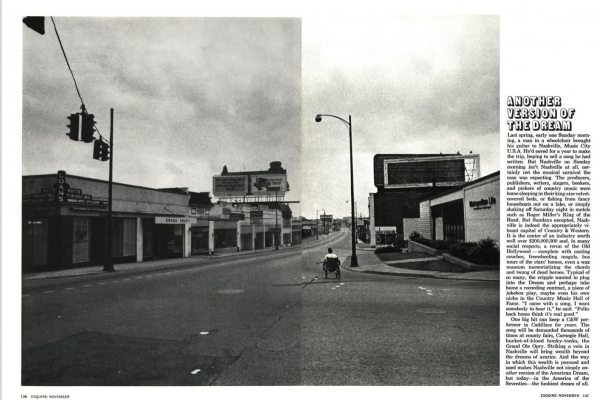

This year not only marks the end of a particular era at Cannes, it closes a chapter on the American film industry as well. Next year, the festival will be housed in its grand new headquarters, and its rhythm and ecology will never be quite the same. For the U.S. majors in attendance, runaway costs, new ownership of the studios the symbolic debacle of Heaven’s Gate and the giant off-screen shadow of cable TV also mean that the business of making movies cannot go on in its present form. Already, at least one major studio, Universal, is shifting from production to distribution – and real estate. Such a course appears to be the wave of the future.

The lessons of Cannes are clear. Movie moguls, always rare birds, are becoming an incresingly endangered species. Having hatched too many rotten eggs at the box office, they’ve lost their glittery feathers and are reemerging as drab little real-estate barons. A spate of summer hits will not camouflage the essential lack of creative imagination in Hollywood today.

Photos by Jean Pigozzi.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.