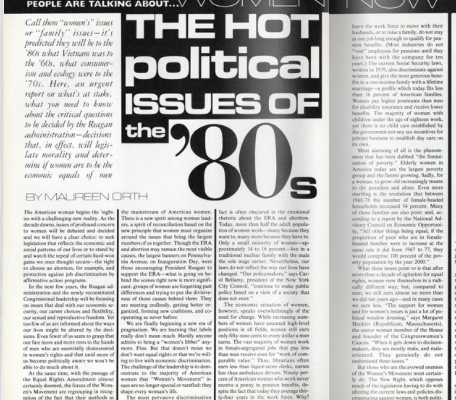

Vanity Fair – May, 1993

The Rainforest Foundation benefit at Carnegie Hall on March 2 started out to be one of those preachy-hip, politically correct, dead in the tundra New York evenings. The stage was littered with stars – Dustin Hoffman, James Taylor, Sting, George Michael, Ian McKellen, Herb Alpert, Canadian rocker Bryan Adams – but even though Tom Jones woke up the audience by belting out “It’s Not Unusual” Vegas-style, the white boys were mostly in the tepid zone.

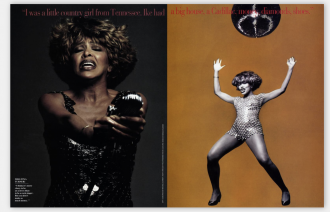

Then came the hurricane. “Ladies and gentlemen, Miss Tina Turner.” Yes. The audience immediately jolted forward in their seats. The queen mother of rock ‘n’ roll, 53 years old, with the body of a vamp, came running out in a tight black leather cat suit with tails and high platform boots. Her hair (piece) was a flying wedge of layered copper, and her powerful voice pierced the darkness like lightning: “When I was a little girl . . . I had a rag doll.” Tina Turner was singing her classic “River Deep, Mountain High,” which the legendary Phil Spector had produced for her in 1966. Those trademark legs swathed in leather, the sinuous moves, those little Pony steps that allowed her to coochie-coochie up to the guys – none of her bountiful energy had dissipated in the 27 years since she first sang it. There wasn’t the slightest hint of the horror she had lived with for so long as a battered wife, or of the dark memories that still cling to her.

James Taylor leapt to his feet and started shaking a tambourine, singing backup. Dustin Hoffman and Ian McKennen joined him. Pretty soon Tina Turner had relegated all the superstar males to an adoring chorus, like cross-dressed ghosts of the Ikettes, part of the R&B roots of rock ‘n’ roll in the old Ike and Tina Turner Revue. Talk about stealing the show. Afterward, Dustin Hoffman told her, “You’ve added 10 years to my life.”

“The first time you see Tina is mind-boggling,” Keith Richards tells me. Adds Mick Jagger, “She’s so gutsy and dynamic.” Tina Turner has always been an icon-mascot to the British supergroups, and even today she is revered more in Europe, where she make her home with her younger German boyfriend, than in the States. The Rolling Stones, particularly, were pivotal in her career. Tina Turner got her first wide exposure to young white audiences in the 60s, when she and former husband, Ike Turner, toured with the baby Rolling Stones in England. “Tina was great-looking, plus she could move and she had that voice. Usually you can have a voice but you can’t move, or you’re good-looking but you can’t sing. How can anybody have that much?” marvels Richards. “With Tina, there it all is – it’s all there.”

Richards remembers that watching Ike and Tina, whom the Stones had idolized from records, was “kind of like school for us.” At that point, he says, “we were one little blues band,” playing bars and tiny clubs with no room to move. “Mick’s stage center was a 12-inch square.” Suddenly they were surrounded by “all these beautiful black chicks in sequins running around backstage, and these fantastic musicians to learn from.” Every night, he says, “we’d do our little bit and then we’d watch Ike and Tina and the Ikettes, realize you got to do more than just stand there and play the guitar.” He adds, “To me it was all just Tina Turner. Ike didn’t see it that way. To him he was a Svengali, who wrote the songs; he was the producer and Tina was his ticket. He saw himself as Phil Spector, as the driving force behind the star. I saw him as the driving force behind a lot of things. It was the first time I saw a guy pistol-whip another guy in his own band.” Keith Richards concludes, “Ike acted like a goddamned pimp.”

To the outside world, however, Tina Turner appeared oblivious. “That was when I was just being led blindly, because I didn’t care about anything,” she says a few days after the Rainforest Foundation benefit. “I was just getting through this period.” She was so under the control of Ike and immersed in his reality that she didn’t have any idea who Mick Jagger was. “I saw this very white-faced boy in the corner with big lips, and I had never seen a white person with lips that big anyway, so I didn’t know who he was or what race he was.”

The one thing she did realize was that “he liked black women, liked to play around with them.” Then she found out that he was the songwriter. “Of course, my hero. He’d say ‘I like how you girls dance. How are you doing that stuff?’ We would all get up with Mick, and we would do things, and we would laugh, because his rhythm and his hips and how he was doing it was totally off. It wasn’t teaching him; it wasn’t dance classes. This is what we did backstage – we played around, because onstage he was just doing the tambourine. He wasn’t even dancing. This was 1966. Afterwards Mick came to America doing the Pony. And all of us thought we had done it backstage. Well, I didn’t tell people I taught him. I said we would just sit around during intermissions and have a good time.”

“Later on, when Tina finally got real big, and she still looked incredible, guys would talk about her image sexually, just as a woman,” Keith Richards says. “But the Tina I knew was different. Tina was somebody to take care of you. Out on the road somebody would always be sick and she would say, ‘Take care of yourself, you have a cold, here’s the VapoRub, keep your scarf on, do your coat up.’ I saw her like a favorite aunt or a fairy godmother. I always had other visions of Tina – of a mother-earth thing.”

“I am a fun person, and when I’m onstage I act,” Turner says. “I like to tease to a point. I’m not teasing men. I am playing with the girls – you know, when all the girls get together and everybody gets up and they get a little cigarette and champagne and they do little things. That’s the same thing I do onstage when I’m performing for the girls and then for the guys.” She is insulted that people would ever assume otherwise. “I am not a vulgar, sexy person onstage. I think that’s how people perceive me, because I have a lot of vulgar videos where they want me to do the garter-belt thing.”

It’s more than that. Who can ever forget Tina Turner doing dirty things to a microphone when she sang “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long,” a song she now hates, or the immortal words in her version of “Proud Mary”: “We nevah, evah, do nothin’ nice and easy. We always do it nice and rough.”

“She has this sensual persona, but her private mores are so old-fashioned, so traditional,” says Bob Krasnow, the Elektra Entertainment chairman “Tina could be your girlfriend, your sister, your best friend – she can fulfill all these emotional niches. Yet when she gets up onstage, she has the power to stimulate you and bring words to life in a way that’s uniquely her own.” Krasnow has never forgotten the time in the 60s when he first walked into the Turners’ house in Baldwin Hills, in Los Angeles, expecting Tina to be a hot number. “She was in the kitchen with a wet rag, down on her hands and knees wiping the floor, wearing a do-rag on her head.”

Today, Tina Turner is nervously steeling herself for the Hollywood portrayal of her rise and fall and triumphant comeback. In June, Disney’s Touchstone Pictures is releasing the film based on her 1986 best-selling autobiography, I, Tina, written with Kurt Loder. The movie, which Tina worries takes too much liberty with actual facts, is titled “What’s Love Got to Do with It?” and stars Angela Bassett (the wife of Malcom in Malcolm X) as Tina, and Laurence Fishburne (of Boys N the Hood) as Ike. The film’s sound track – Tina’s old standards plus three new songs – will come out this month, just in time for her grand concert tour of America and Canada this summer, the first time she’s toured in six years.

Tina Tuner is clearly testing the waters. “I don’t believe that I can go on and stand and sing for the people,” she tells me. “I can’t stand the idea of just standing there like Barbra Streisand or Ella Fitzgerald or Diana Ross. I have never been that kind of performer. I have been in rock ‘n’ roll all my life. You can’t be a rock ‘n’ roll old man.” “If there’s anybody around who can grow up and still be a rock ‘n’ roll woman, it’s got to be Tina,” says Keith Richards, now 49 himself. “She’s in the same position I and the Stones are. It’s out there to find out. The area’s open.”

Tina Turner likes to spend money – oodles of it. She doesn’t look at the price tags. She often buys duplicates of her designer clothes in case the cleaners wreck something. She collects antique furniture, owns a house in Germany and is renovating another in the South of France, drinks Cristal champagne, drives a Mercedes jeep, and indulges herself with massages, facials, psychic readings, and holistic cures. She’s sold 30 million records since 1984, when “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” soared to No. 1 on the pop charts and her Private Dancer album spawned three additional hit singles and swept the Grammys. Although she hasn’t had a hit record in seven years, on her last European tour, in 1990, she filled stadiums and played to 3.5 million people, outdrawing both Madonna and the Rolling Stones. So she’s hardly hurting.

But not long ago her accountant called her and told her, “You’ve been having a good time.” If she wanted to keep the perfumed bubble bath filled to overflowing, it was time to turn on the faucet again — go out and strut her stuff for millions of dollars while the movie was playing and the sound track was being released. Not that she feels particularly like singing onstage – doing that every night with her extraordinary, God-given talent is all wrapped up in her mind with hideous memories of beating and indentured servitude. She’s rather act. “I think it’s more classy to be an actress than to be a rock singer. But you don’t make as much money. I ain’t no dummy. I know that.”

So this year Tina Turner has moved from Europe and rented a furnished house in Beverly Hills, in Benedict Canyon, a Mediterranean- style house that’s all white stucco, beamed ceiling, and bleached wooded floors, with hillsides of daisies. She greets me at the door in a long tan sleeveless knit shift and brown suede Chanel ballet slippers. We go on a tour of the house, which is lovely, low-key and tasteful. The most interesting part is an enormous walk-in closet the size of a bedroom, filled with 10 pieces of Vuitton luggage, about 60 pairs of shoes, and racks and racks of designer clothes, mostly in neutral colors, which she coordinates and tends herself. Inside that closet is a smaller, cedar closet, in which a wig identical to the auburn layered short cut she has on is suspended from a wire hanger, like a spider hanging from a thread.

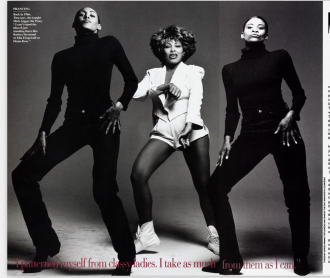

The house is quiet, and filled with fragrant white roses and tuberoses. It’s a place Tina Turner can be a lady. Refinement is something she has always aspired to. “I patterned myself from classy ladies. I take as much from them as I can but I take it naturally, because I’m not going to be phony about it. I’m not going to walk around in Chanel suits or Gucci suits – that’s a bit too much, because that’s not my nature. But watching my manners, caring about not being overdressed at the wrong time – it matters how I carry myself – that’s what I’m concerned about as far as being a lady. Nobody would ever think that Tina Turner is a lady. I am.”

Even in her bleakest years, when life was defined by driving up to 600 or 700 miles a day 365 days a year – when she might be up singing with black eyes and blood “whooshing into my mouth” – she dreamed of her idol, Jackie O. “The first time I met her, I was nearly in tears,” Tina recalls. “In those days I wasn’t thinking about anybody in my circle or the clubs where I was. I was thinking that nobody was at the level of what I wanted in my life – you understand?” Even stardom, when it came, did not make much difference. “It was not my priority.” Not at all. “Music life was not attractive,” she says. “It was dirty. It was a chitlin circuit – eating on your lap. And that’s why I say I was always above it. Why I don’t know, but I knew I didn’t want it. I’d rather go and clean a white person’s house, where it is nice, than sing in dirty old places and deal with Ike and his low life.”

Today, of course, it’s different. Tina Turner speaks of “classy ladies” acknowledging her. “I see a lot of ladies these days in places like Armani, and even those ladies come over and say ‘You look so good.’ ” Does that make her feel good? “To be accepted by another class of people? I am going to say yes, absolutely.”

But love also does have something to do with it. Erwin Bach, the “very private, conservative” 37-year-old managing director of the giant E.M.I. recording company in Germany, with whom she shares a house in Cologne, has been Tina’s boyfriend for 6 years. “He doesn’t like to be discussed, because he’s a businessman,” she says. “It took three years for us to get together – it wasn’t one of those run and jump-in-bed situations.” They met when he was sent by the record company to give her a jeep to drive around Germany in. She didn’t even know his name, and for two and a half years he had no idea, when their paths crossed occasionally, that she was smitten. “Oh yeah, first sight. It’s an electrical charge, really, in the body. The body responds to something,” Tina explains. “Heart boom-bama-boom. Hands are wet. But I said no.” Then again, she thought, why not?

“Something happens to you when you’re secure as a woman. I began to feel, Well, I’m fine. If I don’t really find anybody, I’m O.K. It’s just those times when you start running the streets, and seeing couples and loving, and watching those movies where there’s a lot of love, you miss being cuddled.” It wasn’t until Bach went to Los Angeles for a visit while Tina was at her house in Sherman Oaks that she included him in a friend’s birthday party at Spago. “Afterwards everyone came to my house, and something magic started to happen. Of course, I was attracted. By then I’m sure he knew that I was . . . I made sure I sat next to him. Because I was also analyzing him, too.” She wanted to know that he wasn’t into drugs, or heavy drinking. “After everyone left, I think we exchanged a few kisses. We started to talk, and I asked him about what his record company is like.” Then he pulled away saying, “ ‘Private life is private life.’ So I didn’t really push.”

“What I did do, to actually get him, was I stayed in Switzerland. I rented a house in Gstaad.” She had a house party at Christmastime in 1987 and invited Bach and some mutual friends. That did it, although since then, because of their work, then tend to be apart more than they are together. “It’s the first time I’ve ever had a real comfortable relationship. I’m not threatened. He’s not jealous.” There are no marriage plans, but she is friendly with Bach’s parents, who have retired to the country and don’t speak English. (She has struggled to learn German, to no avail.) “I believe they would prefer if Erwin had a German girl or a white woman. But when they met me, well, it’s the usual. Everybody likes Tina.”

For good reason. There’s a warmth and utter guilelessness to Tina Turner, plus an awesomely strong constitution – though her independence and sense of security have been won at a very high price. Physically, at 53, she is in superb condition. And just because “in California everyone goes under the knife,” that doesn’t mean Tina does. She was terribly hurt when the director of the movie implied that she must have had work done on her face. “I pulled my hair back. I showed them there were no scars. I pulled my ears. I said, ‘Look, this is me.’ . . . .

I almost wish I wasn’t wearing a wig, because then you can see there are no scars,” she tells me. “They don’t take into consideration that I’ve been singing and dancing – and that’s exercise – 35 years. It’s got to do something. I have muscle. From control.” To prove her point, Tina Turner leaps off the sofa where we’ve been chatting and begins to pull her knit shift up, up, up those fabulous tawny legs up past the knees, the thighs – “I still have little-girl legs” – up past her old-fashioned white panties to the just slightly thicker waist, up, up, over the taut breasts. She’s wearing no bra. With her shift now around her shoulders, she turns to the side to show off the profile of her high, rounded bottom. At that moment Roger Davies, her Australian manager, strides into the room. “Oh, Roger!” she gasps and quickly lets the dress fall.

What’s really remarkable about Tina Turner’s face is how few scars it bears from the years of beatings she took. The one operation she did have to have was for a deviated septum in her nose, to open one nostril because it had been punched in so much. Ike Turner struck her on a regular bases for 16 years with everything from shoes to coat hangers to walking canes, plus he once put out a burning cigarette to her lips and also threw boiling-hot coffee on her face. He cracked her ribs. He made her perform with jaundice, with tuberculosis, nine months pregnant, and three days after having a baby. Following her one suicide attempt, in 1968, when she thought she had timed her overdose of Valium to take effect after a performance so Ike wouldn’t lose the night’s receipts, he tried to revive her, saying, “You wanna die, motherfucker, die!”

“She was scared to death of him – everybody around him was, in his own little cult,” says Ike and Tina’s longtime road manager, Rhonda Graam, who is today Tina’s assistant. “It was almost like a hold he had on people.”

“This was always just bruised,” Tina Turner tells me, pointing the her jaw. “This was always just torn apart, because it hits the teeth” she says, showing me the inside of her lower lip. “So the mouth was always distorted, and the eyes were always black. If you look at some of the earlier pictures, my eyes were always dark. I couldn’t get them clear. I thought it was the smoke or whatever. But Ike always banged me against the head.” She is kneeling on the sofa now, clutching a pillow, leaning her face in close to mine. When she pushes up the bangs of her wig, you can see a tiny part of her fuzzy white hairline. “I said the same thing – how could I have survived? Only once I got knocked out. Only once. And that was when I got this,” she says, and runs her finger along the outer tip of her right eye, where there is a scar about a half-inch long. “Yeah, black eyes, busted lips – somehow I just ignored it, but people knew. I thought that they thought it was a car accident. I made something up in my head in terms of the public.”

Tina rarely went to the doctor after her beatings – “just those major things.” The medical people who treated her were of no help. “In those days, believe me, a doctor asked you what happened and you say ‘I had a fight with my husband,’ that was it. Black people fight. They didn’t care about black people.”

Along the way there were many people who witnessed Ike’s mistreatment of Tina, but no one ever intervened. “I felt great responsibility for Tina, and I’d be there while it was going on,” admits Bob Krasnow. “I was young, and I hero-worshiped Ike in a perverted way. Had I been more liberated or more experienced, I would have spoken up. I didn’t.” Krasnow says the horror really began after Ike discovered cocaine, in the late 60s. “The whole thing took this huge turn for ugliness. Tina was the focus for a lot of this horror, but the whole world suffered. In those days there was no Oprah Winfrey, no publicity dealing with abuse, no abuse hot lines. She was out there by herself in a man’s world – she was on the road with B.B. King and Chubby Checker. She was the only woman in this world . . . a demeaning man’s world.”

Tina Turner hates talking about being beaten, and she can’t stand the idea that people consider her a victim. In an era in which victimization is venerated and loudly proclaimed, she rejects the label and wants nobody’s sympathy. She says she wrote the book to stop talking about it. “It’s like going back into time, when you are trying to understand how prehistoric people lived. I am saying it one last time, and I hope people don’t even think about talking to me about it anymore. If they don’t understand, fine.”

The problem is, Tina Turner herself is still struggling to come to grips with why exactly she stayed around a man who brought her so much misery. We spend hours discussing why she tolerated not only the physical and psychological torture but also the scores of other women Ike flaunted under her nose – Ikettes, groupies, employees, nannies for the four children in their house: his two and her two, one by a musician in Ike’s band before she became involved with Ike, and one they reluctantly had together.

One minute she’s defiant on the subject: “I tried to explain it to Disney [for the movie].” Lost cause. She says they see “a deep need – a woman who was a victim to a con man. How weak! How shallow! How dare you think that was what I was? I was in control every minute there. I was there because I wanted to be, because I had promised.” The next minute she says, “O.K. so if I was a victim, fine. Maybe I was a victim for a short while. But give me credit for thinking the whole time I was there. See, I do have pride.” In fact, she’s stymied. “I’ve got to get somebody else to say, ‘Yes, Tina, I do understand, and there are no buts.’ ” Finally, there is a moment when Tina begins to pace, and her eyes fill with tears. “What’s reality sometimes is not exactly real. Because you keep saying, ‘What did I do?’ you get on your knees every night and you say the Lord’s Prayer, and you say, ‘Somebody must send some help to me, because I’ve never done a thing in my life to deserve this.’ And that’s when I started to chant.”

Anna Mae Bullock never knew anything but domestic strife. She was the result of an angry, unwanted pregnancy, and by the time she arrived on November 26, 1939, her mother and father, the majordomo of a cotton plantation in Nutbush, Tennessee, were fighting constantly. One day her mother just took off, and for years never even bothered to contact her two little girls.

“My mother was not a woman who wanted children.” Tina says. “She wasn’t a mother mother. She was a woman who bore children.” Her father tried to cope for a while, but then he too split. “I was always shifted. I was always going from one relative to another. So I didn’t have any stability.”

“Ann” considered herself too gawky to be desirable. “I was very skinny when I was growing up. Long, long, legs and nothing like what black people really like. I must say that black people in the class where I was at the time liked heavier women.” She was living part-time with a white family, doing cleaning for her board and going to high school – just singing along to the radio – when her mother appeared to take her to St. Louis, where she was working as a maid. Ann first laid eyes on Ike Turner when she was a junior in high school and went out to a club one night with her sister. She was 17, he was 25 and a badass star in East St. Louis. Ike Turner and the Kings of Rhythm were the biggest deal around, but, Tina says, “he had a bad reputation. He was known as ‘pistol-whipping Ike Turner.’ “ She knew he had “an uncontrollable temper: but he was also very exciting. After months of begging him to let her sing, she finally grabbed the mike one night during a break and blew his mind with her voice. “I wanted to get up there with those guys,” Tina remembers. “They had people on their feet. That place was rocking. I needed to get up there with that energy, and when I got there, Ike was shocked, and he never let go.”

Ike Turner, a preacher’s son whose father was shot by whites who accused him of playing around with a white woman, had already walked from Mississippi to Tennessee and been recorded by Sam Philips of Sun Records – the first company to record Elvis Presley – when he met Ann Bullock. Today, Ike Turner is credited with recording one of the first rock ‘n’ roll songs, “Rocket ’88, “ in 1951, but he never got anything for it. He was a great rhythm-and-blues musician who played the piano in the boogie-woogie style that Little Richards and Jerry Lee Lewis later adopted, as well as the guitar.

At first Ike and Tina were just friends, and he confided to her that he felt small and unattractive, that in school girls would sneak out to cars with him but no be seen with him, that he was constantly being left and being ripped off of his songwriting and publishing rights. “My problem, little Ann, is people always took my songs!” Wide-eyed Tina – who was well aware that he had women, both black and white in every neighborhood in St. Louis, that he beat those he was closet to, and that he kept guns and bragged about having robbed a bank – promised that she would never leave him like that; she would help him make it to the top. “I was his vehicle to get him to being a star. That’s why I had no say,” she declares. “He was being a star through me. I even saw it then.” She would deeply regret her promise to stay, but she kept it for nearly two decades.

“Ike had some kind of innate quality about him that you really loved him,” Tina says. “And if he liked you, he would take the clothes from his back, so to speak.” Tina makes it clear that “I was there because I wanted to be. Ike Turner was allowing me the chance to sing. I was a little country girl from Tennessee. This man had a big house in St. Louis, and he had a Cadillac, money, diamonds, shoes – all of the stuff that a different class of blacks would look up to.”

Tina got pregnant by one of Ike’s musicians and had a baby boy, Craig, in 1958. The musician left before the baby was born, and Tina worked in a hospital during the day to earn more money, while continuing to sing at night. After club dates, she would sometimes spend the weekends at Ike’s house, where she had her own room. “Then he offered me more money, because one of his singers had left. That’s when the relationship started. I cannot tell you how wrong it felt.”

Sex with Ike and shame, it seems, were always linked in Tina’s mind. She says the first time he touched her felt like “child abuse.” The second time, she was seeking refuge in his room because two musicians had threatened to rape her. “Something was going on – maybe the feeling he could protect me.” Ann was hooked. “That’s the kind of girl I am. If I go to bed with you, then you’re my boyfriend.” She hastens to add, however, “It wasn’t love in the beginning; it was someone else who I found to give love to.” Ike had a common-law wife named Lorraine Taylor, who was pregnant at the time, but he took care of Ann too. “He was giving me money for singing. He went out and bought me clothes. I was having a dental problem, and my mother didn’t have money at that point for dental work. He corrected all that. And then I was a little star around him. I was loyal to this man. He was good to me.” But she was never very attracted to him physically.

“I really didn’t like Ike’s body. I don’t give a damn how big his member was,” Tina says blithely. “I think that must have been very attractive to a lot of white women. I swear, the first time I saw Ike’s body, I though he had to body of a horse. It hung without an erection, it hung with an erection. He really was blessed, I must say, in that area . . . Was he a good lover? What can you do except go up and down, or sideways, or whatever it is that you do with sex?”

Well, you can get pregnant, and a year later Tina was pregnant by Ike. Lorraine – who had previously threatened Tina with a gun, then shot herself instead – was still around. By then Ike and Tina’s first hit, “A Fool in Love,” was climbing the R&B charts. Along the way “Ike did pull a few strings that would make it difficult for me to leave.” He changed Ann’s name to Tina – she says it reminded him of Sheena the jungle queen from the TV series – without consulting her, and she hated it. Worse, out on the road everyone thought the two were married. From the beginning, she never really felt good about him or herself, and looking back today, she can enumerate six or seven reasons why she eventually knew in her heart that one day she would have to leave him.

One night she was crushed to hear him on the radio with an Ikette he was passing off as Tina. Then she realized he wasn’t going to give her her own money. At the same time, she began to realize her importance: “I was the singer.” Her sullen unhappiness inevitably brought a beating. She was stung once again when their baby, Ronnie, was born in 1960 and Ike didn’t take her to the hospital – he slept through it. That was just the beginning. When Ronnie was about two, Ike and Tina moved to California. Lorraine had left Ike by then, and without warning she sent the two sons she had had by Ike to live with their father. Tina was suddenly mother to four boys under the age of six. (Until Lorraine’s boys were in their teens, the didn’t know Tina was not their real mother.)

Tina was not around very much either. Ike was obsessive about work and had Tina and the band and various Ikettes out on the road year-round. It was a rough, cash business; Ike didn’t believe in banks. He had a safe in the house, a safe in the car, and lots of guns to protect him. When Tina was allowed to go shopping, he would peel bills off a big wad.

They put out dozens of records, and some of their songs became hits, but they never made the top 10, only the rhythm-and-blues or soul charts. Nevertheless, Ike and Tina were becoming hip, cult favorites, regularly booked into the Fillmore West. Within five years Ike himself was able to book them where few black acts like theirs had been before, including Vegas. At the International hotel, they were in the lounge and Elvis Presley was the headliner.

They had gotten married in 1962, in Tijuana, primarily, Tina says, because another woman who had been married to Ike before Lorraine was after him for alimony. “As far as I’m concerned, I’ve never been married,” Tina says. “This woman was asking or money, so Ike felt he’d better marry me so she couldn’t get property.” According to Tina, Ike paid the woman $15,000 to go away. For about five years, Tina says, “I was caught in his web.” But about 1965, when she came home from touring alone to find that Ike had moved another woman into the house with the children, she felt defeated once again, and began to entertain thoughts of getting away.

“I had gotten to the stage where I started to think that I didn’t want to be Ike’s wife, and I didn’t care about the money,” Tina says. “I was thinking the whole time, how could I fulfill my promise and get out of it all right?” In 1966, Phil Spector paid Ike $20,000 to let Tina record – but mostly to stay away so that he could work with Tina alone on “River Deep, Mountain High.” Tina was thrilled to be able to really sing. “Nobody wanted me to sing in those days. They wanted me to do that screaming and yelling.” Although the song is considered a rock ‘n’ roll milestone, and became a huge hit in England, it bombed here. Yet, however much Tina may have wanted to go off on her own, she didn’t, for fear that “Ike would kill” anyone who tried to wrest her away.

She was trapped. “I had to get out of there because whatever I was doing didn’t matter anymore. I had my house, I had my children, I had my own car. I had stuff. I shopped. But I had this horrible relationship I was hiding behind.”

Then she got to the stage of not caring. “I wanted him to find a woman.” She told him she wanted a business relationship. “He would really fight harder then, because he thought he was losing control.” “He was afraid she’d leave him,” say Rhonda Graam. “ He would keep the fear going. He didn’t want her to talk to anyone else – to put thoughts in her mind.” Nevertheless, he kept acting like a husband, Tina says, and right up until the day she left him he expected her to massage him, give him manicures and pedicures, and have food ready for him at all times. Sometimes, after beating her, he’d force her to have sex with him. “Sex had become rape as far as I was concerned. I didn’t want Ike near me. It was more than not being turned on and having to do it without being turned on. It was the fact he was sleeping around. That was not my style.”

Nor were drugs. “I could not visualize putting something up my nose.” But Ike was becoming a heavy cocaine user, spending thousands of dollars a week on the drug. He also began to drink. The drugs only made Ike more flagrant with women, even in front of the children. “There was all kinds of sex going on at the house, and I had caught him on the sofas, and women on their knees. I said to him, ‘You can’t do this in this house.’ I really felt this house was mine. Ike was at a stage of showing off. He built a recording studio not far from the house. He wanted to let people know he had an apartment in the back of the recording studio, that he had recording-studio living quarters and the building next door as an agency, and he wanted to come up and show off the house, which was decorated like a bordello, with a coffee table in the shape of a guitar.”

Tina attempted to leave once, but Ike caught up with her at a terminal where her bus was stopped. Her suicide attempt had also failed. But the following year, 1969, Ike and Tina had toured in the U.S. once again with the now humongous Rolling Stones. What really kept Tina going, she says, was her escape into believing what psychics told her: “One day you will be among the biggest of stars and you will live across the water.” In the interim, she chanted more and more every day: Nam-myo-ho-renge-kyo.

In California in the late 60s and early 70s, this particular Buddhist chant, the mantra of a controversial Buddhist sect, Soka Gakkai, was touted as a way to achieve your goals as well as inner harmony. A woman Ike brought to the house one night shortly after Tina’s suicide attempt turned her onto the chant. (Tina actually made friends with a number of Ike’s women. “All of them weren’t bitches or sluts.”) She remembers, “I never let go of the Lord’s Prayer until I was sure of those words.”

Gradually Tina became convinced that chanting was her path to salvation. She was thrilled in 1974 to accept her first movie role, the Acid Queen in Ken Russell’s Tommy (she did not know at the time that acid was a reference to LSD), and desperately hoped for more roles in films, but they did not come. She played Aunty Entity in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, with Mel Gibson, but turned down the leading role in The Color Purple, saying it was too much like real life to her. Today she still says, “I feel there is a calling inside me to act.”

She also appeared on a television special with Ann-Margret and saw a different way of working. “I didn’t want to sing anymore. I had been tired of this singing and this whole image of how I looked. I hated how I looked,” Tina says of her raunchy “Proud Mary” days onstage, when she leaned back and led with her crotch and legs, and her wigs went flying. “The hair and the makeup and the sweat – I hated all of it.”

In 1976 the day finally came when Tina Turner felt strong enough to get away. She realized Ike was never going to give her their house, which she had always wanted and felt she deserved. The children were graduating or getting ready to graduate from high school. Ike, meanwhile, was involved with the “nonsinging Ikette,” Ann Thomas, who had had his baby and was traveling everywhere with Ike and Tina. By then Ike was doing so much coke that he would stay up for three or four days at a time, and his preferred mode of travel was to sleep on airplanes with his head on Ann’s lap and his feet on Tina’s.

In early July they flew to Fort Worth to perform a date at the Dallas Hilton. Tina was wearing a white Yves Saint Laurent suit on the plane, so she refused some chocolate Ike handed her. He kicked her, and later battered her again and again with his hand and shoe in the back of the limo. This time something clicked. She understood. “I knew I would never be given my freedom. I would have to take it.”

She astounded Ike by fighting back. “When someone is really trying to kill you, it hurts. But this time it didn’t hurt. I was angry too.” Tina remembers “digging, or just hitting and kicking. By the time we got to the hotel, I had a big swollen eye. My mouth was bleeding.” She refused, however, to cover the blood, as he directed her to. Ike was in sad shape himself. He had been up for days, strung out on coke, and when they got to the room she massaged his head, as she often did, until he passed out. Tina waited for his breathing to tell her he was asleep. “My heart was in my ears.”

She remembers thinking, Now is the time. You are headed toward dealing with what you’re going to have to deal with, with this man. “I ran down the hall, and I was afraid I was going to run into his people – his band and his bodyguards. So I went through an exit and down the steps. I was so afraid . . . because everybody was aware that Ike and Tina were supposed to be on in half an hour. Then I turned and went through a kitchen, just running. I just dashed through and went through the back door, and I remember throwing myself up onto trash cans just to rest, just to feel I had gotten away. Then I composed myself and thought, Now what? I started to run fast, just run.”

She had 36 cents and a Mobil credit card.

“I needed to call somebody with money. My family didn’t have the money for a ticket. That’s the whole thing always. I didn’t know anybody with money. They were all Ike’s people.”

Tina’s life away from Ike began with the manager of the Ramada Inn across the freeway from the Hilton giving her a suite for the night. Ike did not take her leaving passively. For two years, people who helped her were threatened, and their houses and cars were set afire or shot into. Tina was unwavering, however; she even lived on food stamps for a while. In 1978 their divorce was final. Tina took nothing because she didn’t want to be tied to Ike in any way. What she did come away with was an astounding debt, since she had walked out on a performance. In addition, Ike always booked them solidly for months in advance, so Tina was held liable for the missed dates.

Michael Stewart, the former head of United Artists, one of the many record companies they had been under contract to, lent Tina money to get an act together and began booking her in cabarets and hotels, where she performed in feathers and chiffon in a disco-inferno-type act. She also did guest shots on Hollywood Squares to pay the rent. “Tina never complained,” Steward said, adding that he knew she would be O.K., because at the height of her in-the-depths period he took her to a movie premiere “and you would have thought I was with Madonna today. The paparazzi swarmed. She was a celebrity.”

“Tina was probably half a million in debt when I took her on,” say Roger Davies, her current manager. She worked it off by appearing in such places as Poland, Yugoslavia, Bahrain, and Singapore. Davies tried hard to get her a record contract, but Ike’s reputation cast a pall. “He told me ‘I can’t get you a record now, Tina. Whenever I say Tina, they say Ike.’” In 1981 the Rolling Stones came to her rescue, and she opened a few dates of their American tour. After a magic night at the Ritz club in New York in 1983, with Keith Richards, David Bowie, and Rod Stewart in the audience, her record company, Capitol, finally agreed to proceed with plans to have her cut an album. At the end of that year, she hit it big in England with the single “Let’s Stay Together.” Then she made Private Dancer. The rosy future the psychics had predicted was coming true. Meanwhile, after 11 arrests, Ike Turner finally ended up in jail in 1990, and served 18 months for cocaine possession and transportation, among other charges.

“I never had no bad thoughts about women. I think about women just like I think about my mother. And I wouldn’t do no more to no woman than I would want them to do to my mother.” Ike Turner is giving a bravura performance on the phone from his new home base, Carlsbad, California, outside San Diego, where he is putting together an all new Ike Turner Review with Ikettes he has scouted in local karaoke bars. He’s 61 now, “overwhelmed about how creative I’ve been lately,” and Tina is a sore subject. “Did I hit her all the time? That’s the biggest lie ever been told by her or by anybody that say that. I didn’t hit her any more than you been hit by your guy . . . I’m not going to sit here and lie and say because I was doing dope I slapped Tina. Because it’s not the reason I slapped her. If the same thing occurred again, I’d do the same things. It’s nothing that I’m proud of, because I just didn’t stop and think.”

Ike has been out of jail – “It was the best thing that ever happened to me: — since September 1991. According to one friend, he tried unsuccessfully to marry four different women in jail so that he could have contact visits. Today he’s off drugs, lives with a 30-year-old blonde singer name Jeanette Bazzell, and says he’s getting his own TV movie together to tell his story. “Whatever happened with Ike and Tina – if we fought every day – it’s just as much her fault as it was mine. Because she stayed there and took it for whatever reason she was taking it,” he asserts. “Why would she stay there for 18 years? You know, I feel like I’ve been used . . . Didn’t nobody else grab her and put her where I put her at.” Ike also denies that he hurt Tina as much as she and others say. “You know, if somebody throw coffee on your face and your skin rolls down your face, it should be some burns there, shouldn’t it? Well, you look at her face real good. When you talk to her, say, ‘What kind of surgery did you have on your face?’ I know damn well she didn’t,” Ike maintains. “She ain’t did shit to her skin.”

All those other women, he says, were not entirely his fault either. Ever since he was “a little nappy-headed boy” in Mississippi working in a hotel, “I would see white guys pull up with their little white girls in their father’s car with the mink stole, and I’d say, ‘Oh, boy, one of these days I’m going to be like that.’” That he succeeded with women beyond his wildest imaginings is Tina’s fault too, he says. “I blame Tina as much for that as I blame myself. Because she always acted like it didn’t bother her for me being with women, unless she seen me with this woman every night, or something like this . . . And this is what be wrong with her. She’d be pissed off about some girl or something, and she would lie and say she wasn’t . . We had fights, but we was together 24 hours a day, and so, other words, she feels more like an employee than a wife, because I would tell her what words to say, what dress to wear, how to act onstage, what songs to sing. You know, it all came from me . . . There is no Tina in reality. It’s just like the story that she’s written. The movie’s not about her. The movie’s about me!”

Ike, in fact, showed up on the movie set one day in a chauffeured white Lincoln and passed out autographed pictures of himself. He didn’t get out of the car except to show Laurence Fishburne, who plays him, how he walks. Such is his fearsome reputation that the producers would not allow Angela Bassett, who plays Tina, near him. They had security guards escort her to her trailer. “By the time I figured out how to sneak out, he’d gone,” Basset says. Fishburne did ask Ike what he called Tina. He said, “I called her Ann.”

Ike tells me, “Tina was my buddy. I never touched her as a woman. She was just my buddy. I would send her to go get this girl for me, go get that girl for me. And if I bought my old lady a mink coat, I would buy her one. And that’s the way we were – just hope-to-die buddies. And that’s why it was never no contract between us. Because I felt we had a bond, you understand, and I never did think that nobody, white or black, could come up and brainwash her. Like, right now I feel she’s totally brainwashed.”

“Why do you say that?” I ask him.

“Because she don’t want to be black. She don’t think she’s black. She don’t even talk black. Money don’t make you. You make money. Do you understand what I’m saying? And I hate stars.”

Ike Turner, who has a white manager and a white publicist, and who is accused by his old cronies, such as record producer Richard Griffin, of thinking “black people don’t have any brains,” has big plans for himself, including guest shots on Jay Leno and Arsenio Hall. The last time he talked to Tina, sometime in the 80s, he suggested doing a TV special. “Ike and Tina, Sonny and Cher – the broken pieces put together with Krazy Glue.” Now he’s thinking Vegas and beyond.

“When I was with Tina, we would open up for Bill Cosby, like in Vegas. I’m going to start by doing stuff like that. Going on tour with Elton John. Going on tour with the Stones. Going on tour people like that.” No matter that he hasn’t talked to any of those people yet. Ike likes Ike. “I got a lot of friends out there,” he says. “I have no shame; it took it all to make me what I am today, and I love me today.”

Tina’s two sons and Ike’s two by Lorraine Taylor, whom Tina reared, are now all in their 30s. The chaos they grew up in has taken its toll. They are estranged from their father, and two, Michael and Ronnie, have seriously battled drugs. Ike’s eldest son, Ike junior, is a musician in St. Louis. According to Tina, because of Ike junior’s legal problems, “he can’t come back to California.” Ike’s son Michael was recently living in a downtown shelter. Craig is learning club management. He wants his mother to open a jazz club for him. Ronnie, her son with Ike, is a bass player. One night after he was picked up for an unpaid traffic ticket, he was stunned to land in the same jail cell as his father. “That made an impression,” says Tina. “He never went to jail again.” Ronnie auditioned for the role of Ike in the movie and also played bass in the movie’s band. Tina has bought houses for both her sons. “I used to tell them I wasn’t the Valley Bank. Now I tell them I’m not the European Bank,” she says. “They call me Mother. I know they’re trying.”

It’s a glorious L.A. Sunday afternoon in March. Tina Turner is bouncing in and out of a chair in an upstairs den flooded with light, giving away her beauty secrets. “I do something about my life besides eating and exercising and whatever. I contact my soul. I must stay in touch with my soul. That’s my connection to the universe.”

“What are you?” I ask.

“I’m a Buddhist-Baptist. My training is Baptist. And I can still relate to the Ten Commandments and to the Ten Worlds. It’s all very close, as long as you contact the subconscious mind. That’s where the coin of the Almighty is.” Every morning and evening, Tina Turner, who keeps a Buddhist shrine in her house, prays and chants. “I don’t care what they feel about me and my tight pants onstage, and my lips and my hair. I am a chanter. And everyone who know anything about chanting knows you correct everything in your life by chanting every day,” she says. “People look at me and wonder, ‘You look so great – what is it you do?’ What can I tell them except I changed my life?”

Just when stardom finally hit big with “Let’s Stay Together,” in 1984, Tina Turner was suddenly subject to frequent colds and coughing fits, even onstage. A friend in London recommended an Indian doctor who practiced holistic medicine. His diagnosis: she still had TB. Tina was sent to a special empty hospital in the country for three or four days of intravenous body-toxin purification every time she finished a stretch on the road. It was a “scary place,” she says. “I watch horror movies. Imagine that Frankenstein or somebody – a mummy – is coming through the door.” The doctor prescribed a special low-fat diet and made his own medicines “from gold dust powder. It is all basically from the earth.” The results were dramatic. “After my second visit to the hospital, my eyes became clear. The whites of my eyes were never clear. They were always just not white. And I started to feel healthy. I had a glow, a light, about me.” Most important, she says, “I started to get energy, to feel strong, to enjoy my work more.”

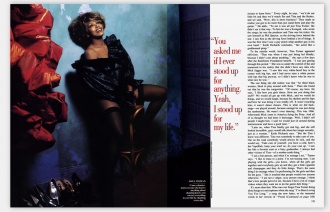

People constantly ask Tina Turner if she will ever do any preaching or teaching. Yes, she says, but not yet. After the tour she is planning to put together a “life-style” cassette detailing her dance steps and holistic cures. Basically, it comes down to this: “I was a victim: I don’t dwell on it. I was hurt. I’m not proud of being hurt; I don’t need sympathy for it. Really, I’m very forgiving. I’m very analytical. I’m very patient. My endurance is good. I learned a lot being there with that sick man.” Like Ike, she wouldn’t change the past. I am happy that I’m not like anybody else. Because I really do believe that if I was different I might not be where I am today,” Tina says. “You asked me if I ever stood up for anything. Yeah, I stood up for my life.”

She’d still rather act than sing. “I stepped into singing. It was hell. It’s still hell without Ike,” Tina says. “I’d like to make money some other kind of way than singing. Especially as an old woman. You can act as an old woman if you’re good enough. I’ll be damned if I’m going to go onstage as a gray old woman.”

But right now, singing is fine enough.What excites me is not the lights; it’s that screaming thing, like when I walk onstage and they go crazy. That’s what happens with Bowie and Jagger, the times I’ve worked with them: they’ve walked on my stage, the whole place went crazy, and I thought, If I’m going to be here, I want that.

Original Publication: Vanity Fair, May 1993.