(See the related interview with Maureen about reporting this story. )

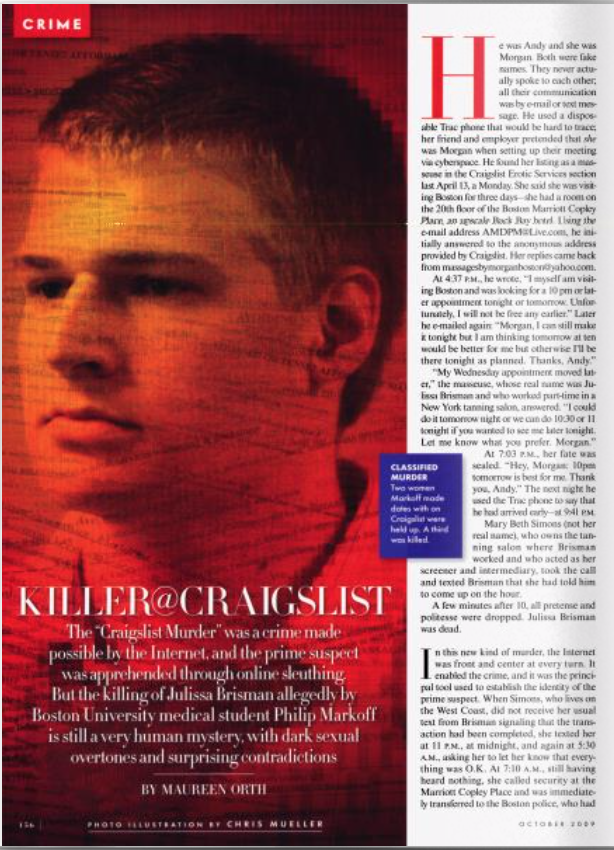

He was Andy and she was Morgan. Both were fake names. They never actually spoke to each other; all their communication was by e-mail or text message. He used a disposable Trac phone that would be hard to trace; her friend and employer pretended that she was Morgan when setting up their meeting via cyberspace. He found her listing as a masseuse in the Craigslist Erotic Services section last April 13, a Monday. She said she was visiting Boston for three days—she had a room on the 20th floor of the Boston Marriott Copley Place, an upscale Back Bay hotel. Using the e-mail address AMDPM@Live.com, he initially answered to the anonymous address provided by Craigslist. Her replies came back from massagesbymorganboston@yahoo.com.

At 4:37 p.m., he wrote, “I myself am visiting Boston and was looking for a 10 pm or later appointment tonight or tomorrow. Unfortunately, I will not be free any earlier.” Later he e-mailed again: “Morgan, I can still make it tonight but I am thinking tomorrow at ten would be better for me but otherwise I’ll be there tonight as planned. Thanks, Andy.”

“My Wednesday appointment moved later,” the masseuse, whose real name was Julissa Brisman and who worked part-time in a New York tanning salon, answered. “I could do it tomorrow night or we can do 10:30 or 11 tonight if you wanted to see me later tonight. Let me know what you prefer. Morgan.”

At 7:03 p.m., her fate was sealed. “Hey, Morgan: 10pm tomorrow is best for me. Thank you, Andy.” The next night he used the Trac phone to say that he had arrived early—at 9:41 p.m.

Mary Beth Simons (not her real name), who owns the tanning salon where Brisman worked and who acted as her screener and intermediary, took the call and texted Brisman that she had told him to come up on the hour.

A few minutes after 10, all pretense and politesse were dropped. Julissa Brisman was dead.

In this new kind of murder, the Internet was front and center at every turn. It enabled the crime, and it was the principal tool used to establish the identity of the prime suspect. When Simons, who lives on the West Coast, did not receive her usual text from Brisman signaling that the transaction had been completed, she texted her at 11 p.m., at midnight, and again at 5:30 a.m., asking her to let her know that everything was O.K. At 7:10 a.m., still having heard nothing, she called security at the Marriott Copley Place and was immediately transferred to the Boston police, who had been combing the crime scene to gather forensic evidence such as hair and blood. She told the officers that she had helped set up the massage appointment through Craigslist, and that she could provide them with the e-mail name and address of Andy. In addition, Simons gave the police the password to the Yahoo massage account. Then Simons called Mark Rasch, the former head of the computer-crime unit of the U.S. Department of Justice and a self-described digital detective, who she knew was an expert in computer forensics. Rasch promptly went to work aiding the police.

The murder was “committed in a very personal, violent way,” says Suffolk County district attorney Daniel Conley. Brisman, who was five five and weighed 105 pounds, presumably tried to resist. As a result, the killer bashed her skull in with the butt of a 9-mm. semi-automatic pistol and shot her three times at close range, in the heart, chest, and abdomen. A woman in a nearby room, after hearing shrieks, went out into the hallway and saw a clothed body sprawled across the doorway of Brisman’s room. A piece of plastic tie was hanging from one wrist.

Only four days before, Boston police had received a report from another out-of-town masseuse, Trisha Leffler. Leffler was staying at the equally upscale Westin Copley Place. She reported that on April 10 she had met with a tall, blond male in his 20s who had answered an ad of hers on Craigslist. She greeted him outside her room, she said, and shortly after they entered he pointed a gun at her, ordered her to lie down on the floor on her stomach, and bound her with the same type of plastic ties found on Brisman. According to Leffler, he rifled through her suitcase, robbed her of $800 and credit cards, and wore gloves to remove his number from her cell phone. He did not attempt to violate her sexually. Then he took his gloves off to gag her with duct tape, cut the phone lines, and left with a pair of her panties. “A lot of this case will rest on the testimony of that first victim,” Conley tells me. “He had her in captivity 15 minutes at least.”

Two days after Brisman’s murder, in Warwick, Rhode Island, about 40 miles from Boston, Cynthia Melton, a stripper who advertised lap dances on Craigslist and danced occasionally at the Cadillac Lounge, in Providence, made an appointment to see a man she had met through the Erotic Services section at the Warwick Holiday Inn Express. He scheduled their 11 p.m. meeting on a Trac phone. Once inside her room, she said, the client, who was wearing a baseball cap, pulled a gun, made her lie facedown on the floor, and bound her with the same type of plastic ties used on Brisman and Leffler. He tried to silence her with a ball gag, a device routinely used in sadomasochistic sex, which is stuffed in the mouth and secured with ties at the back of the head, but she kept shaking her head no until he finally gave up. Melton told authorities that the tall, blond young man had been extremely nervous, and that he was trembling as he rummaged through the room looking for her cash and credit cards, telling her, “Don’t worry, I’m not going to kill you. Just give me the money.”

At that point her husband happened to knock on the door. According to the couple, when the assailant pointed a gun at him, Keith Melton instinctively started walking backward down the hall until he tripped and fell. The assailant fled down a nearby stairwell. His entrance to the hotel had been caught on surveillance tape while he was texting. One of his texts that night was traced to the area of a nearby Walmart, where at 10 o’clock he had bought the baseball cap he wore during the attempted robbery. Walmart’s cameras established the purchase.

Life Without Privacy

Few Americans, even those from the younger, Internet generation, seem to understand how easily their clicks and text messages can be detected, and how little privacy any of us have anymore. Every search, every posting, every text message or Twitter, leaves a cyber footprint. The content of every e-mail sent by any one of us is kept by the Internet service provider and stored for a period of time, usually six to nine months. Google and Gmail used to store e-mails indefinitely; now they claim they’re within the same range, but all the e-mail we choose to keep until we delete it can also be accessed by the provider. “If you can see them, they can see them,” says Rasch.

Boston law enforcement started backtracking to find out Andy’s identity, first establishing that the e-mail account at Live.com came from Microsoft in Redmond, Washington. Next they had to find out who was accessing that account and from where. “They used legal processes [court orders and search warrants] to get Microsoft to disclose the unique computer-ID number, or I.P. [Internet-protocol] address, that was used to send the e-mail answering the Craigslist ad,” Rasch explains. Craigslist was able to see what time and date the user of the Live.com address responded to each of its postings—when he clicked Morgan’s or the other two women’s ads, for instance. “People who use Craigslist leave more of a trail than people who just use the phone,” says Rasch. Conley goes further: “People feel online communication is pretty discreet. That’s entirely false.” (Hotel security services routinely monitor Craigslist to see how much of the erotic trade they are attracting.)

The police searched the hotel’s surveillance tapes to see who appeared on-camera just after the killing. Simons’s phone call and her text to Brisman right before the killer got to Brisman’s room made the timing precise. The surveillance tapes showed that, just after the killing occurred, a tall, blond, white male matching Leffler’s description of her attacker was looking down and working his phone while walking briskly but nonchalantly away from the Marriott Copley elevators. Surveillance tapes at the Westin Copley revealed a remarkably similar-looking person texting upon leaving that hotel in the time frame of the Leffler holdup. “He doesn’t seem to rattle very easily,” says Conley.

The police also got important clues about the AMDPM@Live.com e-mail account—what information the subscriber provided when it was created and the I.P. address of the computer used to create it. “What they learned was that the e-mail account was a throwaway account, created a day or two before, just for the purpose of making these connections,” says Rasch. “But they still had to figure out who was sending the e-mails.”

The address came back to an Internet service provider in the Boston area. “The provider was able to give the police the name and address of the customer to whom they had assigned the particular I.P. address. This doesn’t mean necessarily it’s the guy, but it’s close enough,” says Rasch.

When the police went to investigate the physical location—8 Highpoint Circle, in Quincy, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston—it turned out to be a large apartment building. The I.P. address was definitely associated with a particular person, but it was a wireless router, “so anybody in the building could have been using this address,” says Rasch. “That’s the nature of wireless. So, while the police had a name and address that got them close, it did not give them the suspect. Anybody within a few hundred feet of the router would be able to access that router and be assigned the Internet-protocol address the police were looking for.” Nevertheless, Rasch says, the first thing police did, once they had a name, was exactly what many of us would do—they went to Facebook and Google to find out who their suspect was and what he looked like. Then they fell back on tried-and-true detective work and began an old-fashioned stakeout. They were shocked to learn who it was they were looking for.

The Competitive Nerd

Philip Markoff, 23, tall, blond, a second- year medical student at Boston University, was arrested on April 20 as he was driving with his fiancée, Megan McAllister, 25, on Interstate 95 in Walpole, Massachusetts, south of Boston. Police had seen him exit his apartment building with the attractive young woman, carrying an overnight case. Ordinarily they would have watched him a bit longer, but they were concerned about how far he might be going. “Once he goes out of state, we lose control,” says Conley.

Markoff had never been in trouble with the law before. He had graduated summa cum laude from the State University of New York at Albany in 2007, and on August 14 he and McAllister, who was also planning to attend medical school, were going to be married in a big fairy-tale wedding on the New Jersey Shore near her hometown, Little Silver. Their wedding Web site detailed their four-year romance—their meeting as volunteers at an Albany hospital, his proposal on a beach in Maine. A Springsteen cover band, the B-Street Band, was scheduled to play at the beachside reception. McAllister’s gown, by Vera Wang, had already been purchased, as had the bridesmaids’ dresses, and listed on the bridal registry were a set of luggage worth $1,600 and Vera Wang goblets. All that would draw derisive comments from Internet posters, who flocked to the Web site after Markoff’s arrest became a media sensation.

McAllister thought they were being pulled over for speeding. Although she had shared the Highpoint Circle apartment with Markoff for the past seven months, she had been away during the period when the crimes were committed, and police soon concluded that she was clueless about her fiancé’s alleged crime spree.

That day the couple were on their way to Foxwoods, a casino in Connecticut, about a half-hour from where the Rhode Island assault on Cynthia Melton had taken place. Markoff had about $1,600 in cash on him, and this would have been his 19th visit to Foxwoods in four and a half months. His first visit had been noted on December 8, 2008, when he signed up for the “Wampum” points awarded as perks for frequent gamblers. His presence had also been documented in the early evening of April 16, the night Melton was attacked. (Police were able to trace his Foxwoods visits by the computer records kept of his “burning Wampum.”)

“He didn’t give up any information,” Conley says of Markoff’s arrest. But while Markoff remained mum at police headquarters in Boston, investigators were searching his apartment in Quincy, which yielded a trove of evidence. The gun that police believe had killed Julissa Brisman, a Springfield Armory XD9 semi-automatic, was hidden in a hollowed-out copy of Gray’s Anatomy, the classic medical textbook. They found a supply of the plastic ties used in all three crimes and quantities of bullets that matched those removed from Brisman’s body. Four pairs of women’s panties were stuffed, two each, into a pair of socks hidden in the box spring of the couple’s bed. There were extra Trac phones and a laptop computer whose hard drive later yielded pieces of Andy’s response to Brisman’s Craigslist posting. They also found 45 $100 bills.

When Markoff was arrested, he was carrying a New York State driver’s license with a photo of one Andrew Miller, who police say had nothing to do with any of the crimes. Police allege that Markoff’s fingerprints are on the purchasing documents for the gun he bought with Miller’s license in Mason, New Hampshire, late last February. His prints were also found on the duct tape used to bind Trisha Leffler’s mouth, as well as on the wall in the hotel room where the assault on Cynthia Melton took place. Shortly before Markoff’s arrest, Boston University medical school gave police his identification photo, which Trisha Leffler picked out in a sequential photo-identifying procedure.

At his arraignment, on April 21, Philip Markoff pleaded not guilty. No one in his family was present at his arraignment, which the press duly noted.

Within his first 48 hours in jail, Markoff was put on suicide watch and moved to the infirmary as a result of some marks on his neck made by his shoelaces. He was seen by a psychiatrist, who declined to have him sent to a state mental hospital. The next day his older brother, Jonathan, and his wife visited Markoff, and the Boston Herald reported an allegedly overheard conversation between the brothers. “Forget about me,” Philip supposedly said. “Move to California.…There is more coming out.”

Sherrill, New York, where Markoff grew up, is a tiny, picturesque town, 35 miles east of Syracuse. The former site of the Oneida silver factory, now shuttered, Sherrill is the sort of place where Professor Harold Hill might come marching up Main Street at any moment. When Philip was still a toddler, his parents divorced. His father, Richard, a dentist, remarried and took his son Jonathan to Syracuse to live with him. Philip remained with his mother, Susan, who subsequently married Gary Carroll, a banker, with whom she had a daughter in 1991. The couple split several years ago, and the daughter lives with her father. No one I spoke to in the small community remembered Markoff’s parents or step-parents participating in activities at his school or showing up very often at the local Community Activity Center, where he excelled in youth bowling leagues. His stepfather, several residents recalled, used to bring his daughter around to sell Girl Scout cookies or to trick-or-treat on Halloween, and he did most of the grocery shopping. “If you saw the family walking down the side of the road, nobody would know them,” said Clint Smith, who graduated a year after Markoff from Vernon-Verona-Sherrill High School. On Thurston Terrace, a well-kept block where Markoff lived in a gray house trimmed in white with a big lawn in back, the family’s next-door neighbor, Molly Waddell, told me, “They were very quiet and kept very much to themselves. They were never any bother.” Sonja Hluska, who taught Markoff English in high school and lived right behind the family, described him as “the nicest young man, polite, respectful, with a good sense of humor.”

To kids and teachers alike, Markoff was a nerd who excelled academically. He did not have a girlfriend. “He was not one of the most popular,” said Hluska. “He had his own group of friends, more interested in computers and science, like Trekkies.” He was a member of the school’s Youth Court, where student judges meted out punishment to under-age offenders in lieu of having them attend family court. He was also on the golf and bowling teams, and beneath his nondescript demeanor he was intense and competitive. In his high-school yearbook he bequeaths his poker-playing skills to a friend and predicts that everyone else will bowl 300 before a certain one of his classmates does. “He was pretty even-tempered and quiet, except he would always get a little too mad at me if I beat him,” said Todd Brown, who had played golf with Markoff in junior high school. Sherrill is in shock that one of its own could be accused of murder. Crime there is “stealing a bicycle,” Lisa Perry, a lifetime resident, told me. Speaking of Markoff’s mother, Molly Waddell said, “Sue was quite devastated. She doesn’t understand what happened. She said it’s so out of character.”

Looming over the town is the huge and controversial Turning Stone casino. It is the county’s largest employer, but because it is located on an Indian reservation it pays no taxes. “It has nicknames like Eyesore,” said Markoff’s high-school classmate Andrew Hookway, who started a Facebook support group called “Phil Markoff Is Innocent Until Proven Guilty.” For several years Markoff’s mother worked at the casino, selling cigarettes and aspirin at a kiosk. Markoff learned to play a mean hand of poker, and he and his friends continued to drink and play blackjack at Turning Stone when they came home from breaks at college, but they did not go over a self-imposed $200 limit. “Some nights they lost that much, but never more,” said a close high-school friend.

By the time he arrived at suny Albany, Markoff had taken so many advanced-placement courses that he sailed through in three years. People who lived with him remarked that there were times when he would spend up to eight hours a day alone at his computer. He rarely if ever talked about his family. He was a biology major and very active in a coed, pre-med fraternity, Phi Delta Epsilon. Within the fraternity, Markoff was an eager mentor and volunteer to some—he came to a Halloween party dressed as a mammogram machine—but to others he was someone who held back his real thoughts and behaved awkwardly and often inappropriately. According to one classmate, “What he was on the inside wasn’t necessarily who he was on the outside.” He would tell pretty girls he was afraid of flunking and get them to spend hours tutoring him; then he would ace the exam. Once, when a group of Phi Delta Epsilon members came home from a night of drinking, Markoff, under the guise of walking his classmate Morgan Houston to her door, pushed her up against a wall and started kissing her, in spite of her efforts to stop him. “I was saying, ‘No, Phil, what are you doing? We’re just friends, I don’t like you. Stop!’” But he did not let up until a male friend of Houston’s pulled him off. Houston had a boyfriend at the time, and she said Markoff’s come-ons made her feel uncomfortable. “It was the way he said it.” But she blamed the incident on alcohol and did not bring it up again. She noted, “At some points he really wasn’t comfortable in his own skin.”

Houston remembers that as a sophomore Markoff was “pretty excited” about meeting Megan McAllister, a strawberry-blonde senior in pre-med. “He was saying, ‘I met this great girl—she’s older.’” In college they basically kept their social lives separate, but they were equally serious about becoming doctors. He got into medical school, however, and she did not.

Since Markoff’s arrest, Boston University medical school has gone into complete lockdown mode. One instructor I spoke with begged me not to mention him, saying, “It’s posted on the Internet all over the university—‘Don’t talk to the media.’” Copies of the B.U. paper that carried the Markoff story were mysteriously unavailable at the medical school. Later, the alternative weekly The Boston Phoenix reported, “An anonymous admissions-office employee told the Daily Free Press that the papers were purposely hidden ‘because of their content, which would reflect negatively on the school.’”

Tiffany Montgomery, who has since dropped out of the medical school, was Markoff’s lab partner. They shared an anatomy locker, and she spent many hours with him in class. She felt he was disturbed, perhaps even suicidal. “I mentioned that to three other classmates, and everyone blew it off.” According to Montgomery, Markoff would go for long periods without communicating with those around him. “You never knew with Phil what you were going to get,” she said. “He wouldn’t look at you when he talked to you.” He often seemed tired and depressed. “He came in once at five a.m., looking like death warmed over. It was the morning of a big exam. He said he had just driven in from New Jersey, because he had had a fight with his girlfriend and he had to deal with it. He could barely bring himself to speak.” At a party they attended, Montgomery told me, Markoff drank a lot and “continued to flirt with people who were really not interested. They weren’t flirting back, but he would just keep it up. He had no real idea of himself—he couldn’t read body language.”

The Only Person Who Ever Loved Him

Getting married between your second and third years of medical school is rather unusual, and Markoff and McAllister were not even planning on being together for months afterward. Following the honeymoon they were going to have to live apart. She had been admitted to a medical school in the Caribbean, where classes would start at the end of August. She planned to go straight through in 14 or 15 months and then continue her studies in the U.S. Meanwhile, he would return to finish B.U. medical school. They planned to get together on breaks.

Suddenly, McAllister’s careful plans were shattered. From the moment she and Markoff were stopped by the police, her life went from wedding invitations and menus to paparazzi and jail. Shortly after the arrest, her father, who sells and installs backyard playground equipment, appeared in front of their house in Little Silver with tears in his eyes to face a phalanx of reporters. No, his daughter was not all right; things were “very tense.” “They thought their baby daughter was marrying the man of her dreams and they’d go off and be happy for the rest of their lives,” says Robert Honecker, the lawyer the McAllister family hired.

McAllister’s first response was total disbelief. She e-mailed People magazine, “Philip is a beautiful man inside and out and did not commit this crime. Unfortunately somebody else did and needs to be penalized. Philip was set up.” ABC News got a similar e-mail: “A police officer in Boston (or many) is trying to make big bucks by selling this false story to the TV stations. What else is new?? Philip is an intelligent man who is just trying to live his life so if you could leave us alone we would greatly appreciate it. We expect to marry in August and share a wonderful, meaningful life together.”

On April 29, McAllister, dressed in black, went with her mother to visit Markoff in jail for 25 minutes. The next day Honecker made the rounds of the morning TV shows, describing their meeting as “emotional” and saying, “The wedding that’s been planned is obviously off.” Honecker hastened to add, however, “There’s been no breakoff of the engagement … Yes, she believes he’s innocent.”

During the time in February when Markoff bought the gun, McAllister, who had had surgery on her back, was going home for medical treatment and spending a lot of time there planning the wedding. Even though the pair had dated for four years, their families barely knew each other, and her bridesmaids had not even met her fiancé. According to people close to McAllister, she considered Markoff brilliant, and she did not worry about his frequent visits to Foxwoods or even about whether he should be gambling heavily during exam periods. The Monday they were arrested, for example, he was facing a final exam in hematology on Friday. But since B.U. medical school was pass-fail, she reportedly figured he would always be O.K. Ironically, just before she returned to Boston that week, her mother had warned her to be careful—a guy there was hurting women. According to someone who knows her, McAllister has been racking her brain to think of anything she could have noticed that would have changed the course of events.

On June 11, McAllister had to appear before the grand jury that would indict Markoff later that month. She took the opportunity to visit him again in jail. Honecker later told the morning news shows, “She let him know that she did not expect to return to Boston,” and that it would probably be “quite a long period of time, if ever,” before she would see Markoff again. When headlines blared that McAllister had dumped Markoff, she had Honecker issue a correction, denying that “she will not or may not ever see him again.” She said she was “the only person who had ever loved him.”

In fact, McAllister believes that each of them was the other’s first love. She was clearly in awe of Markoff’s intelligence and saw him as a protector. I had a brief phone conversation with McAllister and Honecker. Honecker said, “Megan’s upset she’s been labeled a country-club blonde. Nothing could be further from the truth. She’s very hardworking, and her parents are hardworking. They don’t belong to a country club.” I mentioned that some people considered her “the bubbly one.” “That’s not true,” she told me in a small, high voice. “He’s very outgoing, and I’ve always been very quiet. We didn’t hang out in the same crowds. I was very, very reserved in high school and college, and he was the outgoing one.”

His Tastes Were Wide and Varied

On Craigslist, in the free-of-charge Casual Encounters section, there are the categories t4m and m4t—Trannies (transvestites) for Men and Men for Trannies—listed city by city. In late April, a week after Markoff’s arrest, Jeff Rossen, of NBC News, broke a story on the Today show about Markoff’s soliciting a transvestite in Boston. In a series of e-mails, they had exchanged photos, including one allegedly from Markoff that could not be shown on national television. Police sources confirmed to NBC that the hard drive of Markoff’s computer, which they had seized, also contained the messages to the tranny.

I subsequently met the transvestite—who did not want his name used—and a friend of his, at a bar in the Westin Copley Place, the scene of the Leffler attack. He told me he had assumed his tranny identity after winning a contest at a Halloween party dressed as J.Lo and being thrilled at how many men bought him drinks. This night, however, he was dressed for his day-job as a corporate consultant, carrying a laptop, which contained every response he had received over the last year as a result of his postings on Craigslist—about 1,500 in all. “It’s not blackmail per se,” he explained, patting the laptop, “but in case I get murdered I have the information to share.” One of the icons on the screen was for his complete Markoff file.

“Hey sexy” was the first subject line. On May 2, 2008, at 12:29 a.m., the name “Phil Markoff” came up with the e-mail address Sexaddict5385@yahoo.com. He was replying to Craigslist personal No. 664395223. “I just saw your cl add, message me on AIM: my1name1is1phil.” (AIM is America Online instant messaging, which doesn’t display spaces in a screen name.) He continued, “I am 6’3” a 22y/o grad student.” Along with the message, he sent his picture, which the tranny verified by going to Markoff’s Facebook page and seeing the identical photo of him there, smiling, in a blue-and-white striped shirt, with a small drapery swag in the background.

At 12:33 a.m. this response was sent: “Hot ass to Phil: You got any more pix, stud?”

A few minutes later Sexaddict sent two attachments: a picture of the buff upper torso of a tall male with the head cut off and a picture of an erect penis with a ruler held alongside it, measuring eight inches.

Hot ass replied at 12:39 a.m., with a picture of himself in short shorts, holding a camera: “Here’s one of me. I will message on AIM in a few.”

At 12:46, Sexaddict got back: “Sorry babe, I’m going to sleep.”

The tranny was offended. At 12:50 he responded, “Not your type or just not tonight, have a good sleep, maybe I’ll catch you later.”

Almost nine hours later Sexaddict picked up the thread: “Hey, I’m still interested. Do you have any more pics? What are you into and what are your stats? What are you doing tonight?”

At 9:34 a.m., the tranny sent two more pictures, but he never heard back. Sexaddict was gone.

Nearly nine months later, on January 27, 2009, at one p.m., in response to another posting from the tranny, who this time was using the screen name Hot tongue, a message came from someone with the initials “PM” (not “Phil Markoff”) and the screen name Sexaddict53885—a second 8 had been added: “Hey, I’m a 22y/o graduate student, 6’3 205, good build, blonde/blue eyes 8 inches cut. Let me know what else you want to see or know about me. Do you have any more pics? What else are you looking for?”

Sexaddict did not realize who Hot tongue was, but he was quickly filled in. At 1:03 p.m., Hot tongue told him that they had chatted before. “I know you are a BU grad student … you’re still hot but I don’t like getting stood up.”

Sexaddict apologized in another e-mail, and Hot tongue asked, “Have you gotten any ass this semester?” Sexaddict responded: “Lol, a little.” Hot tongue was willing to give him another chance, but no reply came back from Sexaddict53885 until 10:38 p.m.: “Hey, I just saw your message. still looking? where do you live?”

“I did not respond,” the tranny told me. “I was in bed.”

On April 22, two days after Markoff’s arrest, the Albany Times-Union reported that when it Googled his Boston phone number one of the four hits was a remnant of an undated Craigslist posting for an “ebony erotic masseuse.” According to the article, “The posting title and preview reads: ‘Craigslist ebony erotic masseuse—taking my last appointment—24. Why get a massage if you’re going to be uncomfortable? I’m sure I will leave you satisfied. My donation is 150 Contact me at 617-481-****.’” In Craigslist-speak, a donation is the euphemism for the price of a sexual service.

According to Mark Rasch, there are several possible explanations for the posting: (1) Markoff did it “to lure johns to come to him”; (2) he did it after “he got the gun to lure people to a hotel room so he could rob them—he may have robbed some people this way”; or (3) “someone else did it and put in the wrong number.” Jake Wark, press officer for the Boston district attorney, would not comment to the Times-Union except to say that Craigslist is cooperating with the investigation. Wark would not comment to me about the tranny evidence, saying it did “not even approach relevance” to their case. But a police source told me that Markoff’s tastes were “wide and varied.” That may be an understatement. A crime blogger recently uncovered evidence suggesting that Markoff once applied as a newcomer for sadomasochistic experiences.

The last time Markoff was seen in public was at his arraignment for the grand jury’s indictment on June 22 in Suffolk County Superior Court, in downtown Boston. I arrived early and was startled to see that the only other people in the spectators’ section of the magistrate’s courtroom were Markoff’s biological parents, his brother—who resembles him but is shorter—his brother’s wife, and an unidentified young man. His mother has a large face, with mousy-brown hair extending just below her ears, and big glasses. She is tall, like his father, who is bald and tanned. They stared straight ahead and barely spoke. At a previous hearing, at which Markoff did not appear, I had been standing next to his mother when she was caught like a deer in the headlights, cowering in the vestibule of the courtroom, with a semicircle of TV cameras aimed to catch her just outside the door. “I don’t know what to do,” she said nervously. “My attorney told me to wait for him here.” I called for bailiffs to help her. At the arraignment, she had to watch her son, who had had such a promising future, led into the courtroom in shackles.

Markoff has an extremely capable court-appointed criminal-defense lawyer, John Salsberg. He got Salsberg because his parents are not helping him financially. He owes more than $130,000 on student loans and has no employment. (Authorities largely discount the widely reported notion that gambling debts might have gotten him into his predicament.)

Shortly before Markoff appeared in the dock on June 22, a group of people slipped into the first row in the courtroom. They were Julissa Brisman’s mother, Carmen Guzman, a slight woman in a gray pantsuit, who does not speak English, and who had a friend and translator with her, and Julissa’s father, Hector, from whom Carmen has been estranged since Julissa was a baby. Both parents are immigrants from the Dominican Republic. The mother was a doctor there and comes from a family of doctors, but she could never learn enough English to get a license to practice medicine here. She had come to Boston, she said, “to see justice for my daughter.” In a statement read by a family spokesman, she called Julissa “the light of our lives. She was also a college student who would have graduated this May with a degree in counseling.”

Although the two suffering families were within a few feet of each other, neither acknowledged the other’s presence. The defendant did not look once in their direction during the entire time the litany of his alleged crimes was being read. Then Philip Markoff turned toward the magistrate and proclaimed loudly, “Not guilty.”

This Wonderful Thing We Call Life

Carmen Guzman is still very raw over her daughter’s death. She breaks into tears at the “lies” she says have been printed about Julissa, calling her a prostitute. Julissa’s sister, Melissa, 15, could not bring herself to go to her adored sister’s burial or to appear in the courtroom in Boston. “She has not come to terms with what happened,” Guzman told me in Spanish.

Guzman last heard from her daughter at 8:30 on the night she was killed. Julissa excitedly told her that she had met a medical student and that they were going to have a date. “I told her not to trust anybody—no one,” Guzman told me. Brisman’s text messages that day to Mary Beth Simons, which authorities now possess, show that she actually did meet a Boston University medical student on the train to Boston. The student was not Philip Markoff, however, and police soon established that he had nothing to do with the crime.

Guzman insists that she did not know Julissa was advertising on Craigslist. “She told me she worked for the tanning salon and was going out of town to help train a girl in a new business.” Brisman was killed 10 days before her 26th birthday, and two weeks before completing a year’s course in addiction counseling at City College of New York, a decision that had been spurred by her own bouts with alcoholism, for which she had been hospitalized at least twice. After nearly a year of sobriety, she was regularly attending A.A. meetings and wanted to help others, particularly young women, overcome the disease. “She was very attractive, young, bright, with a lot of potential—she had a drive about her,” her counselor told me. “I work in a field where 75 percent don’t make it. This girl came with a purpose.”

On her MySpace page, Brisman described herself as a “true born and raised Manhattan hottie, finally getting ahold of this wonderful thing we call life!!!!” In May 2008, her entry was indexed by MySpaceProfiles.org, providing yet another way she could have been traced on the Internet. She chronicled her primary interests: “acting .. I live it .. I breathe it—it’s my Passion!, FasHion ShowS (and shopping after!!), Broadway Shows, CoNcErTs, I loVe ‘SeXy TimEz’—Hanging out and spoiling my GorGeOuS dOg, CoCo ChAnEl! He’s the Man of my life!! oh ya!!”

Guzman raised Julissa in a building on West 107th Street, before the area got gentrified. She took advantage of neighborhood enrichment programs and gave her daughter dancing, ice-skating, and riding lessons. Julissa had a number of jobs—selling shoes, waitressing, clerking at Macy’s. In 2003, while working at the department store, she acquired a criminal record by pleading guilty to a charge of grand larceny, a charge that was later reduced. Her mother told me, “A girl stole clothes from Macy’s, told them that Julissa knew about it, and then she disappeared. Julissa said the girl was lying. Julissa paid it all back.”

With her friend Deisy Lynn, Julissa went to bartending school and became a bartender. At a number of places she did not last long. “The owners would like her, come on to her, and she’d leave,” said Lynn. “She was very picky. She didn’t like guys hitting on her if they were ugly.” She added, “She was used to Craigslist, because that’s how she got her bartending jobs.” Lynn said Brisman felt driven to help her little sister and buy things for her. She finally decided to quit drinking because it made her mother suffer.

With the big tips gone and college courses to pay for, she tried other ways to make money. “She had the body,” said makeup artist Emily Claire, who did Brisman’s makeup for the head shots she needed for auditions. “Long thin legs and her own breasts.” She never landed any decent roles, however. Instead, Brisman told Claire, she would fly to places such as Chicago “to do these parties. She made it sound like it was these wealthy guys in groups, almost like a strip club but without the lap dances. Girls would walk around in bikinis or topless and serve drinks and chat. She’d do it once a month and get paid $1,000.” However, she insisted to Claire, “I would never touch those guys. That’s so gross.” She also became a sensual masseuse. Her counselor said he had tried to talk her out of it, but she told him, “I need to take care of my sister.” He added, “I know she wasn’t in it for prostitution.”

Carmen Guzman recalled a young woman at Julissa’s funeral, pushing a six-month-old baby in a stroller. “She told me Julissa helped her with her drinking problem. She said Julissa saved her life and her baby’s life.” Unfortunately, she could not save her own.

Sex and the Internet

“If the Internet is Walmart, every aisle is filled with every sex fetish you can think of,” says former Washington Post tech reporter Jose Antonio Vargas. “Ten percent of all searches on Google and Yahoo are areas which are porn-related,” says Jules Polonetsky, co-chair of the Future of Privacy Forum, a think tank and advocacy group in Washington, D.C., that is supported by major high-tech companies. “The Internet has created a world where we are all virtually connected all the time to everyone else in the world. The social implications of that are just being understood.” He adds, “We’re all in an electronic soup. You go to sell your couch on Craigslist in an hour, or you meet someone for sex in the next half-hour. It’s immediate.” Vargas credits Craig Newmark, the founder of Craigslist, for “the revolutionary idea that on the Internet we can trust each other. But can we?”

The attorneys general of 43 states, led by Connecticut’s Richard Blumenthal, think not. “We objected almost two years ago to the blatant and flagrant prostitution ads and pornography that were rampant on Craigslist and led to the murder in Boston,” says Blumenthal, referring to the Julissa Brisman case. “They were certainly enablers insofar as their ads linked the victim and the alleged killer, and they had fair warning their ads were putting people in danger.” Last November, the attorneys general got Craigslist to toughen its rules by requiring a working landline or proper cell phone, a valid credit card, an e-mail address, and an I.P. address that can be traced back to the individual from everyone placing a posting on Erotic Services. Blumenthal says that he and others had a “very blunt, tough meeting with Craigslist people in New York shortly after Brisman’s murder. No question the murder not only electrified the nation, it also impacted their view of the world.” The attorney general of South Carolina threatened to hold Craigslist criminally liable for the Erotic Services postings, but he backed down when Craigslist fought back with an injunction against him.

In May, Craigslist announced that it was eliminating its Erotic Services category in the U.S. (though not in 50 countries abroad) in favor of an Adult Services category, which Craigslist C.E.O. Jim Buckmaster tells me is “manually reviewed to make sure a human reviewer looks at each ad and picture, reads each word, and compares the ad with our posting guidelines.” The company also employs “content-filter software,” which is supposed to catch a lot of violations at the initial stage. He says that each month Craigslist gets 40 million new ads and 20 billion page views. One percent of the ads are sex listings.

Detective Steven Schwalm, of the Washington, D.C., vice squad, says, “Craigslist didn’t mean to start out creating a cyber-brothel, but that’s what it grew into.” Schwalm’s boss, Inspector Brian Bray, division commander of the D.C. police force’s prostitution unit, adds, “There are so many prostitutes on Craigslist in this area alone—hundreds. It makes everything so much easier. They know their ads are for criminal purposes.” Buckmaster counters, “That is a false statement. I don’t feel Craigslist is in any way responsible for these crimes. It is a tool that can be used for positive or negative actions.”

Section 230 of the Federal Communications Decency Act states that Internet sites cannot be held liable for what third parties post. “There is an entire virtual world that exists without boundaries,” says Fred Singer, C.E.O. of the Web-video-syndication company Grab Networks and former head of AOL’s instant-messaging and content divisions. Singer says of Craigslist and other online communities, “[They’re] creating cities without police forces, because if you don’t police it, you can’t be sued, because you are not responsible.” Buckmaster disagrees, arguing, “The site is heavily policed in all sorts of ways: content filters, staff removal [of offending postings]—our users’ flagging system is quite effective. In reality, we are heavily policed … if need be by police officers.” Blumenthal says, “Craigslist is very cooperative with law enforcement after the crime is committed.”

In the Markoff case, according to Buckmaster, “police did contact us and requested information, and we supplied all the information we had.” He adds, “All three crimes are connected, and those cases are linked, and when we were asked to provide relevant information we did so.” Buckmaster says it is very foolish for criminals to use Craigslist. “It virtually guarantees they’ll be caught.”

Boston district attorney Daniel Conley says that, although “juries like us to connect the dots,” he is not required to prove a motive or explain why Philip Markoff would allegedly attack and rob the two women accusing him or why he would allegedly murder Julissa Brisman. To prove murder, Conley has to prove intent to kill. To do that, his office will use all the evidence the Internet has provided. He thinks he has a compelling case.

No Comments