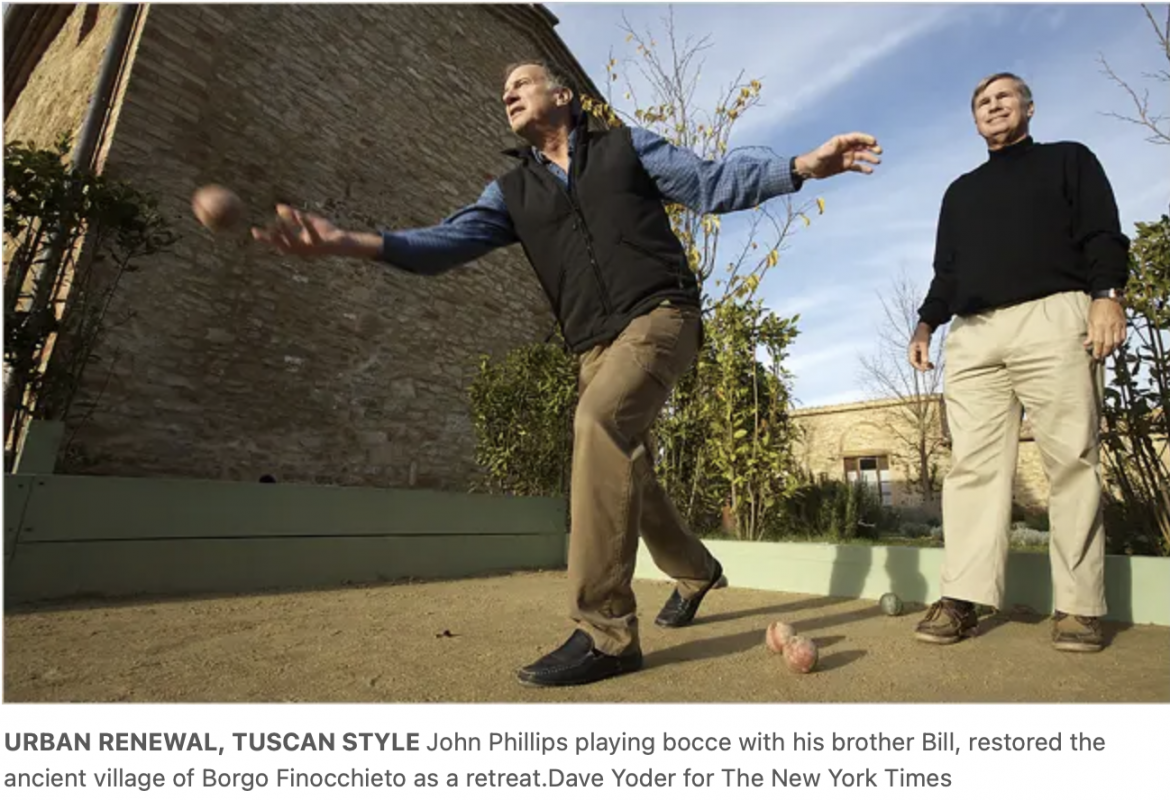

Original Publication: New York Times – January 11, 2007.

Buonconvento, Italy

JOHN PHILLIPS spent more than two years looking for a villa in Italy before he saw Borgo Finocchieto near this town in Tuscany. He had always imagined having a place in Italy — his original family name was Filippi, and he had fallen hard for the country in 1969, after a lonely tour of Eastern Europe. What he had never imagined, until that day in the fall of 2000, was that that place would be a village.

A tiny medieval farming town, Borgo Finocchieto (the name means village of fennel fields) was little more than ruins and piles of dirt when he first came here. He had been sent by a friend proposing a joint purchase: Mr. Phillips, a Washington lawyer, would buy the main house and the friend and two others would buy the rest. The borgo’s five acres and five dilapidated structures were part of an estate once owned by the Borghese family, and overlooked a valley of hills and vineyards. Mr. Phillips said he was instantly struck by the view, uninterrupted and virtually unchanged for 1,000 years, and by the silence: the site was the quietest he had visited in Italy.

The borgo, which appears on a map from 1318, is about 40 miles south of Siena, close to the ancient Florence-Rome road used by Chaucer and Michelangelo. It was farmed by peasants and sharecroppers. As late as the 1960s, 21 families shared the borgo’s large U-shaped manor house, living on the second floor without indoor plumbing and keeping their livestock sheltered beneath them on the ground level. When Mr. Phillips saw it, the village’s onetime chapel had become a barn, and an ugly tractor shed blighted the view of the countryside.

Mr. Phillips decided the borgo should be brought back to life as a single entity, and in 2001 he bought it himself in what he called “a moment of irrational exuberance.”

Mr. Phillips, now 64, could afford to buy and renovate the borgo after decades as a public interest lawyer, during which he earned cuts of the considerable money that he helped recover for the California and federal governments from contractors accused of corruption. But he wondered whether he and his wife, Linda Douglass, then a correspondent for ABC News, really had a use for so many houses in the Italian countryside — even given their large extended family and network of friends. He decided that the borgo should double as a gathering place for “people associated with charitable and educational issues.” Its beauty and history could help inspire creative thought and dialogue, he hoped; it would be nice, he joked, “to have the Mideast peace talks here.” (He would charge for these gatherings, he said, but was not interested in making a profit; he has also considered renting the borgo out to select business groups to help finance the plan.)

But before Mr. Phillips could remake the borgo, he had to face the formidable hurdle of the Italian government’s historic preservation entities, which had declared it a “place of special significance.” He shrewdly hired Amalia Agnelli, a former head of the preservation committee here in Buonconvento, as his architect. Even so, two years of planning were required before construction could begin.

“Rebuilding was expected to be totally consistent with what was there before,” said Mr. Phillips. “If there was a window 300 years ago that had been covered up, you could put the window back, but you could not add a new window.”

In Italy, there are records dating back centuries that detail the exact size and shape of many buildings, and even the materials used for the original interiors. There were approximately 30,000 square feet to reconstruct, including the manor house, the barn (which would become a five-bedroom house), the chapel (four bedrooms) and two two-bedroom cottages, for a total of 23 bedrooms that could sleep 46 — and all of it had to fit within the buildings’ original volumes.

Nearly four years later, the project is only now being finished. Mr. Phillips estimated its value at about $30 million, thanks largely to the Tuscan real estate boom of the last few years and the strength of the euro, although his own costs were probably less than a third of that.

Since he could not be around to supervise his ambitious plan on a daily or even monthly basis, Mr. Phillips assembled a team of friends and friends of friends, many of them British and American expatriates who had retired to Tuscany and spoke at least some Italian. One of the group’s first decisions was to use only local materials, artisans and labor, for authenticity.

“There was not going to be a single thing here that has been brought over from the United States,” said Karen Hartmann, a former Boston kitchen designer who became the borgo’s decorator.

The manor house, with its original stone staircase leading to a long corridor entryway, would have suites for both the Phillips family and the family of Mr. Phillips’s law partner, Mary Louise Cohen, who now visit frequently. There would be nine other bedrooms, a formal living room, two large dining rooms, a modern kitchen that could be used to prepare meals for 100, a ballroom-conference room and a bar, library and wine cellar with an antique grape press.

Mr. Phillips also requested some very unborgo-like features, including a gym and an 18-car garage that Ms. Agnelli buried under the lawn, a pool, and a tennis court that the preservation committee allowed her to build in place of the tractor shed.

Mrs. Hartmann, meanwhile, traveled twice a month to the antiques markets in Lucca and Arezzo, getting to know dealers of 18th-, 19th- and early 20th-century antiques and their sources for restoration. She found the large marble-topped credenza which sits at the top of the stone stairs in the manor house at a wine festival in Buonconvento. For coffee tables, she bought small tables of dining height and had them cut down. She wanted a farmhouse style for the interiors featuring colors and tiles that were traditionally rustic but could still be elegant. Most of the walls were stuccoed in traditional ochre or terra cotta. In the manor house the antique white walls of the original dining room featured a stenciled design around the ceiling molding that had been in the house for several hundred years, which Mrs. Hartmann copied in the new dining room. She also bought copies of antiques.

“These were going to be pieces that were going to be touched, handled and sat on — they can’t be precious,” she said. “We’re in the country. That’s really the message here.”

She hired former blacksmiths in Buonconvento to do ironwork, and other craftsmen from nearby towns — a woodworker in Sinalunga who could fashion intricately inlaid tables, a family in Poggibonsi that made and hand-painted copies of antique wooden headboards. The only items not from Tuscany were the handmade ceramics from Amalfi.

Mrs. Hartmann planned far in advance so as not to overwhelm vendors like her Siena upholsterer, who did not have the space to work on 10 sofas at a time. She found that efforts at bargaining rarely paid off.

“They don’t sit there and calculate how much you are going to spend,” she said of the local business people. “They set a price. They are much more responsive if you are appreciative of their work and time and respect how many years and generations and families are involved,” she added. “It is very important to have conversations with them.”

Mr. Phillips also did well in hiring a local chef, Luigi Ricci, who as it happened had just retired to the next-door village of Bibbiano after 30 years of working for Paul Bocuse in Lyon. Because turkey is scarce in the area, Mr. Ricci prepared veal when Mr. Phillips brought his extended family to the borgo last Thanksgiving. But more recently, Mr. Ricci learned that a neighbor was raising a turkey. After a month of plying the neighbor with his desserts, he produced the bird as part of a New Year’s Eve dinner in the manor house’s formal dining room.

No Comments