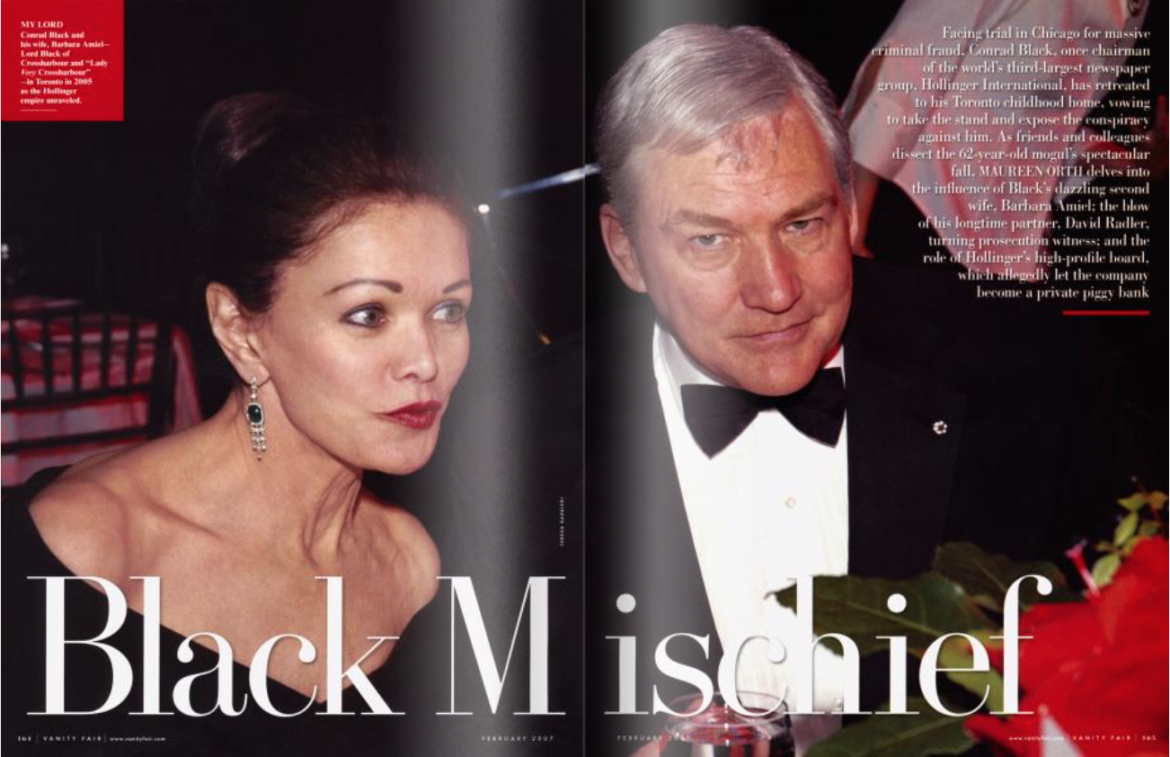

Vanity Fair – April 2, 2007

Conrad Black, Canada’s most famous non-citizen, is home again in Toronto, awaiting trial in Chicago in March on 14 counts of criminal fraud, racketeering, obstruction of justice, money-laundering, and mail and wire fraud. Once the powerful chairman of the third-largest newspaper group in the world, Hollinger International—at its peak the owner of the London Telegraph, the Chicago Sun-Times, The Jerusalem Post, and more than 500 community newspapers in Canada and the United States—Black at 62 is facing a maximum of 101 years in prison, $164 million in fines, and forfeiture of assets in excess of $92 million. Apart from the criminal charges, Black is also facing numerous civil suits, including two major ones from Hollinger International (recently renamed the Sun-Times Media Group) and Hollinger Inc., the Canadian holding company that controls more than 70 percent of Hollinger International’s voting stock.

“He’s home in every sense of the word,” his closest friend, Brian Stewart, a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation correspondent, tells me over lunch in Toronto. “Back to the house where he grew up. He can stand in front of the huge weeping-willow tree he planted with his mother.” Berner, the old German butler, is still in attendance. The Black mansion sits on seven acres in an area called the Bridle Path, a neighborhood now shared with the rock star Prince, newly rich Russians, and the Casino King of Macao.

Of all the corporate tycoons charged with fraud in recent years, Conrad Black is certainly the grandest, the one who lived highest and moved in the most distinguished circles. A political conservative, he gave up his Canadian citizenship, in 2001, to sit in Britain’s House of Lords, as Lord Black of Crossharbour. He is also the author of an acclaimed biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt. His indictment truly stunned the elite he had cultivated so assiduously in Canada, England, and the United States. Black maintains that his current circumstances are due to nothing more than bad paperwork, governance zealots, and “bullying” and “self-righteous” shareholders. To get through this “period of suffering,” Stewart says, Black—a convert to Catholicism from Anglicanism—is relying on his faith, “believing that suffering will be followed by redemption, even though he has no idea why he is being tested at this time.”

“Substitute vindication for redemption,” Black answered when I asked him about this in an e-mail. “It is very rare that anyone plausibly claims to know why any severe and unjust affliction occurs to anybody. We don’t have much insight into the reason for such things.” Stewart predicts a “substantial settling of accounts.” Black, he says, “wants to go to Chicago, smash the conspiracy against him, and win. He will then have a comeback and a whole new round of lawyers and lawsuits.” Black apparently is determined to testify on his own behalf, to face down the evil U.S. judicial system. He now defines himself as a “freedom fighter.” The strategy, however, is extremely high-risk, considering his overbearing demeanor and the withering cross-examination he will be subjected to. More than $100 million has already been spent on legal fees in this case—picked up mostly by Hollinger International and its insurance fund—and Black has reportedly gone through 33 lawyers. Nevertheless, Stewart says, “this is the only way to clear his name.” Ken Whyte, editor in chief and publisher of the Canadian magazine Maclean’s and another close friend of Black’s, agrees: “He’s filed several lawsuits and will probably file more. He’s got a substantial file of articles presenting charges against him as ‘proved’ as opposed to ‘alleged.'”

Government authorities and those in charge at Hollinger today, however, claim they have plenty of insight into how Black and his executives did business. In addition to a total of 17 criminal counts, Black and other Hollinger officials stand accused by their company and shareholders of diverting more than $400 million—about 95 percent of Hollinger International’s profits from 1997 to 2003—into holding companies by which they controlled the conglomerate. The diversion of most of that money, however, was approved by Black’s handpicked board of directors, composed of glittering socialites, political titans, and prestigious businessmen. The mortified board has already agreed to settle a shareholders’ lawsuit for $50 million, to be paid by the company’s insurance.

Last September, Black’s lawyers sought to have the entire criminal indictment thrown out, arguing that it cast too many aspersions on the rich way he lived. The defendant would be unable to get a fair trial, the documents argued, because a typical Chicago juror “does not reside in more than one residence, employ servants or a chauffeur, enjoy lavish furniture, or host expensive parties.” Black’s only true peers, the argument seemed to imply, might be in the House of Lords. For years Black had taken delight in conspicuous and promiscuous consumption. Now, in their brief, his lawyers actually quoted Matthew 19:24—”It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” U.S. District Court judge Amy St. Eve, who is presiding over the Black case in Chicago, denied the motion.

“The Distraction”

What a mighty fall. Black grew up in privilege, though his gifted father died a depressed and isolated alcoholic, thwarted in his career as a brewery executive and forced to retire early. Many believe Black’s path in business is an attempt to avenge his father. According to Stewart, “His father died enormously bitter, feeling betrayed by his firm and business partner. He lived a hermit’s existence in the mansion.” Conrad, says a former high-ranking Canadian official, “was primarily impressed as a son with the business elite of Toronto—an elite his father was not well treated by. So he set out to become the key person with enough ambition to prove himself in this elite.” In the process, Black had to overcome tremendous insecurity. “He has a child-like hunger that cannot be assuaged,” Stewart says. “He is driven by the need to be somebody, to be noticed, that is beyond the norm. He has a totally tin ear when it comes to his P.R. persona.”

Before Black was ousted as C.E.O. of Hollinger, in November 2003, he seemed to have acquired all the accoutrements of material success—residences in London, Toronto, and Palm Beach; two apartments in New York (one for servants); and two private jets. As Black’s strikingly beautiful and strikingly controversial second wife, Barbara Amiel, once put it, “It is always best to have two planes, because however well one plans ahead, one always finds one is on the wrong continent.”

The Blacks at their Palm Beach estate, now collateral. Photograph by Jonathan Becker.

Black is Amiel’s fourth husband. A fearless right-wing journalist and avid Zionist, she also served on Hollinger’s board and held the title of “vice president, editorial” at the Chicago Sun-Times, where between 1998 and 2003 she earned $1.3 million for producing a few columns and occasionally critiquing the paper. A former girlfriend of British book publisher Lord Weidenfeld and screenwriter William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men), among others, Amiel at 39 wrote an autobiography detailing her hardscrabble youth in Canada and her former addiction to the antidepressant Elavil. Canadian gold tycoon Peter Munk, who once served on the board of Hollinger Inc., compares Amiel to the late Pamela Harriman in her ability to seduce men: “Pamela had family heritage, of course, and Barbara had brains. She had to make up for the heritage in other ways.” Four years older than Black, Amiel was a top columnist for the London Times—fiercely opinionated, tightly wound, extremely well constructed, and just as interested in power and influence as Black. She was a true femme fatale, and Black was swept away. When they married, in 1992, Vanity Fair chronicled their honeymoon in Maine, where David Rockefeller lent them his cabin, and the dinner thrown for them by the onetime doyenne of New York society Brooke Astor.

They became “London’s most glamorous power couple,” as the weekly Spectator later put it, known for attracting everyone who was anyone to their annual summer cocktail party and lavish Christmas party at Cottesmore Gardens, their 12,000-square-foot, 11-bedroom manse, in the Kensington section of London. Black rode around the city in a restored Rolls-Royce, cultivated Margaret Thatcher, and had Tony Blair speak at one of his advisory-board dinners. It appeared that all of Black’s dreams had come true, particularly once he was named to the House of Lords. “That meant a lot to him,” says London society figure David Metcalfe. “He could speak in the House of Lords as a way to hold forth on a bigger platform to address various subjects on which he’d be an authority. That’s different than talking to yourself in the bathroom.”

But the old hunger for more never left Black, and one of the most common theories for why he finds himself in such a pickle today is the influence of the bewitching Lady Black. “She’s part of what I call ‘the distraction,'” Jeremy Deedes, the former chief executive of the Telegraph, tells me. “Barbara is a five-star girl, and she needs five-star maintenance. He was willing to do whatever she wanted, it would appear.” Deedes adds, “Barbara ruffled feathers with her views. ‘I think I better ask the little woman,’ he would say when certain subjects came up. I think she was giving orders.” According to Con Coughlin, the former executive editor of The Sunday Telegraph and now executive foreign editor for The Daily Telegraph, “The same people who were briefing Judy Miller and The New York Times were briefing The Daily Telegraph—all of that [Iraqi politician Ahmad] Chalabi nonsense was being reflected through Barbara.”

Charles Moore, a former editor of The Daily Telegraph, says, “She gave him a better understanding of journalism and supported us. What I hadn’t bargained for was her trying to influence the paper regarding individuals. It was surprising. She led him away from the company of journalists to the company of the super-rich.” Peter Munk notes, “Conrad is a starfucker—has been all his life. He got turned on physically by fame or prominence.” Before Barbara, according to Moore, an ideal evening for Black would have been dinner with “[former secretary of state Henry] Kissinger, [journalist William F.] Buckley, some British columnist, Margaret Thatcher, [Iraq-war conceptualizer] Richard Perle.” Within a few years, however, according to Moore, favored guests included Donald Trump, Princess Michael of Kent, philanthropists Lily Safra and Jayne Wrightsman, “café society, Fergie, people you didn’t think of him with, Joan Collins. He did want society’s acceptance. I could never quite figure out whose.”

Certainly, Hollinger International’s board, on which Barbara served, was rife with clues. Its members, some of whom were paid as much as $25,000 per meeting plus annual fees, included—in addition to Kissinger, Weidenfeld, and Perle—Marie-Josée Kravis, president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and wife of business mogul Henry Kravis; former Illinois governor “Big Jim” Thompson; Richard Burt, former ambassador to Germany; Robert Strauss, former ambassador to the Soviet Union and former chair of the Democratic Party; Leslie Wexner, founder of the Limited; Alfred Taubman, former head of Sotheby’s, who served a 10-month jail term for price-fixing; and Dwayne Andreas, the former chair of Archer Daniels Midland, which paid a $100 million fine for price-fixing, and whose son, an executive of the company, went to jail.

Hollinger’s international advisory commission, handpicked by Black, a largely conservative enclave of mighty has-beens with more prestige than power, included Thatcher, former French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, former Israeli president Chaim Herzog, former secretary-general of NATO Lord Carrington, the late Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli, former national-security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, and journalists Buckley and George Will, both of whom wrote favorably about Black without disclosing that they each received about $25,000 annually from Hollinger. This group would gather to dine and discuss world affairs while Lord Black showed off his photographic memory and his vast knowledge of history. (And he did all the seating himself.) Shareholders paid in excess of $1 million in expenses for the advisory commission alone.

Today, Hollinger International’s board stands accused of having drunk too much from the wizard’s poisoned chalice, approving the transfer of hundreds of millions of dollars that are alleged to have gone into Black’s and his cronies’ pockets instead of into dividends. The board routinely acted on the recommendation of the audit committee, whose members, Big Jim Thompson, Marie-Josée Kravis, Richard Burt, and Richard Perle, were at one point served by the Securities and Exchange Commission (S.E.C.) with Wells Notices—warnings that if they could not explain their behavior to the government’s satisfaction they could be permanently barred from serving on the boards of publicly listed companies. (The S.E.C. has since dropped its probe into the former directors.) The board has also been excoriated by an investigative special committee within Hollinger International, a committee the board itself was forced to form in 2003 in the wake of shareholders’ complaints. In a scathing, 513-page report to the S.E.C., the special committee chronicles in painstaking detail the alleged wrongdoing, going so far as to accuse Black of presiding over a “corporate kleptocracy.” The report cites the audit committee dozens of times for being “inert and ineffective” and for “its inexplicable and nearly complete lack of initiative, diligence, or independent thought.” Perle was singled out as a “faithless fiduciary.” Christopher Browne, of Tweedy, Browne, the private-investment firm that brought the original charges, says, “The tragedy of the criminal suit is that the $32 million that Conrad [and the others] took without board approval is so small relative to what the board let him take.”

Thus, not only is Black facing serious jail time, but a number of the power figures he brought onto his board are facing shame and possible ruin. “When you pack the board with people who don’t know the difference between business and ballet,” a big-time Wall Streeter tells me, “when you have a phony board, part of the world—the social world—thinks it’s great. The financial world smells a rat.” Former S.E.C. chairman Richard Breeden, counsel to the special committee, who supervised the drafting of the report, adds, “Often, politicians and former public officials make terrible board members. There are certain things absolutely not done in business, and politicians frequently don’t know that.” Edward Greenspan, Black’s Canadian lawyer and his chief legal counsel, scoffs at this notion. “Just because they are luminaries does not mean they are not financially astute,” he says. “Kissinger was almost chairman of the board of the world.”

Torys, an international law firm, was accused of conflict of interest for representing both Hollinger Inc. and Hollinger International, and for standing by while funds were diverted to Black. It has settled for $30 million. So far, KPMG, Hollinger’s longtime auditing and accounting firm, though under fire for illegal tax shelters elsewhere, has been able to dodge a very big bullet. In the face of numerous alleged felonies by Black and the others, Hollinger International has decided not to sue KPMG, feeling that it was more important to bring its filings up to date with the S.E.C., which could be done only with the accounting firm’s help, than to go after it. One of the lawyers suing Black says, “The entire loss could have been avoided if the auditors had said something.” (Interestingly, Breeden, the special committee’s chair, was subsequently named as a special monitor to address KPMG’s legal woes.) Today, both Torys and KPMG are slated to be witnesses for the prosecution.

Conrad Black’s defense will doubtless lean heavily on the premise that the board, as well as the experts at Torys and KPMG, knew exactly what they were doing every time they said yes to him—including approving retroactively the purchase of $8 million worth of Franklin Roosevelt’s papers. One board insider claimed to me that they had no idea at the time that Black had been writing a book about Roosevelt. The board also approved more than $200 million in excessive management fees paid to Ravelston, a holding company owned by Black and his associates, which once controlled Hollinger Inc.

To prove Black guilty, the prosecution will have to show that he lied to the board, and therefore that—since Hollinger’s lawyers and auditors raised no objections—the sophisticated board members were played for fools. It will be fascinating if Richard Perle, who the special committee says profited enormously from his service on the board, and Marie-Josée Kravis, who did not, take the witness stand, knowing that their statements could be used against them in ensuing civil suits, which require a lower burden of proof.

What Is Black Living On?

In Chicago in December 2005, when U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald first indicted Black and four others, Black entered the courtroom slowly and ceremoniously, slightly dragging the toe of first one shoe and then the other, almost as if he were still wearing his ermine-trimmed cape from the House of Lords. Tall, silver-haired, and commanding, he displayed a slight smirk, as if to say, “I am putting up with this charade. For now.” Black gazed at those of us in the press warily. Though he had made his fortune in journalism, he once characterized investigative reporters as “sniggering masses of jackals.” He has referred to his enemies as “pygmies.”

Bail had been set at $20 million. Among the lawyers Black has retained since 2003 are David Boies and John Warden, who faced each other in the Microsoft anti-trust case; Brendan Sullivan, who defended Oliver North in the Iran-contra scandal; and Greg Craig, Sullivan’s colleague at Williams & Connolly, who has represented Bill Clinton, U.N. secretary-general Kofi Annan, and Elián González, the six-year-old Cuban refugee. In October 2005, Craig filed a suit protesting the F.B.I.’s interrupting the closing on the sale of Black’s New York apartment and seizing the $8.9 million purchase check, thereby depriving Sotheby’s real-estate brokers of their commission (which in turn generated a suit against Black brought by Sotheby’s) and Williams & Connolly of $6.8 million it was owed in legal fees. The apartment check was used by the government to help guarantee Black’s bail; his Palm Beach estate, which has been on and off the market, is guaranteeing the rest. To complicate matters further, the Canadian government already had a lien on the Palm Beach property as part of its $900 million tax dispute with Hollinger Inc. and Black.

A question of interest to everyone is: What is Black living on? A project manager at Black’s Palm Beach house tells me that once, several months ago, he received a call from the I.R.S., the F.B.I., and the U.S. Postal Service—all on the line simultaneously—demanding information about whether company money was used to pay for renovations. In June 2006, Black made a jaw-dropping donation of $450,000 to the Canadian Opera Company from his family’s foundation, ultimately setting off a series of legal fireworks over how much money Black really had and how much he should be allowed to spend. When judge Amy St. Eve found out that the Blacks were going through $200,000 a month despite having no apparent income, she wanted to know, “Where’s the money coming from?” So did multiple jurisdictions on both sides of the Canadian border, all of whom are coveting the same property. Documents disclosed that Barbara Amiel had lent her husband at least $2 million, but the money’s provenance was murky. St. Eve raised the bail to $21 million. Meanwhile, Fitzgerald in August brought additional charges of tax evasion. Within days a Canadian court froze all of Black’s assets worldwide because of a $700 million amended lawsuit by Hollinger Inc., and the Blacks were put on a strict allowance of about $20,000 a month each. The assets were unfrozen after Black’s attorneys negotiated a secret arrangement in Ontario. Recently, three of Black’s co-defendants have filed a motion to separate their trials from his. The legal plot developments become more tortuous with each passing day, and there is a point when the only sane response is to call it a complicated mess, and move on.

The criminal trial is scheduled to begin in March at the earliest, and the court has ruled that until then all discovery-related civil actions, including defamation suits Black has brought against Henry Kissinger, other members of the board, and Richard Breeden, must be halted so as not to interfere with the criminal case. (In his multi-billion-dollar defamation suits against Breeden, the special committee, and others, Black castigates them for turning him into “a social leper” and “loathsome laughingstock.”) In the meantime, prosecutors must go over more than a million documents. They will be attempting to prove that Black and others pocketed more than $80 million for agreements—allegedly made by misleading the board or without board authorization at all—that they would not compete with community newspapers they had just sold to a Canadian company called CanWest for $2.1 billion. Non-competes are common, but usually the compensation goes to the company, not to individuals. In Canada, non-competes are not taxable, whereas if these amounts had been labeled as bonuses they would have been.

In addition, Patrick Fitzgerald has brought charges against Black for having the company pay for a portion of his wife’s $62,870 60th-birthday party, at La Grenouille, in New York; for allegedly undervaluing the price of the New York apartment he had bought from the company; and for using the company jet for a vacation on Bora-Bora, at a cost of $530,000. Black is already in a vulnerable position with the S.E.C., owing to a 1982 consent decree he has been under for questionable dealing in the purchase of a stake in a Cleveland mining company. Therefore, the lawyer mounting his defense cannot expect to have an easy time.

“Fast Eddie” for the Defense

Edward Greenspan greets me in his Toronto office on a Saturday morning, formally attired in a gray pin-striped suit and clutching three pages of single-spaced typed notes of points he wishes to make regarding his client Lord Black. Greenspan is 62 and has a pale face and wavy hair. This is not Enron or WorldCom, where investors lost life savings, he emphasizes, but mostly rich institutional investors griping about share price. Sitting at an antique desk next to a tank of tropical fish, he quickly warms to his subject. In the Canadian bar, Greenspan is known as “Fast Eddie,” someone you go to when almost all is lost, someone who thrives on headlines. He has never tried a case in the United States, but he has a special waiver for this one. He has said he hopes to drop dead on a courtroom floor someday, right after the foreman says, “Not guilty,” and the Black case is his big chance to show off in a high-profile U.S. federal court. In a TV documentary about him, Greenspan declares, “I love to cross-examine. I don’t stop when I have somebody on their knees—I won’t stop!”

These days he has a fixation about taking down Breeden, who chaired the special investigation. “When you’re on what you believe to be the moral high ground, thinking seems to go out the window,” Greenspan says of Breeden, who, he promises, will be slapped with a billion-dollar libel suit as soon as Black is found not guilty. “He went hell-bent for leather in terms of coming after Conrad Black, who in a bunch of e-mails that have been made public has called Breeden a fascist and a crook. So that has obviously upset him, the sensitive Mr. Breeden, and zealots can be very dangerous and use expressions like ‘corporate kleptocracy.'”

Greenspan blames Breeden especially for the high bail Black had to meet, and says Breeden is trying to bankrupt his client. “Breeden, the son of a bitch, made a suggestion that Conrad Black was going to take the money and run,” Greenspan says. “He created that hysteria. It is so unbelievably wrong. Anyone who knows Conrad has always understood he will stay for any fight, especially one involving himself and his reputation.” He adds, “Breeden is the one that yelled, and by yelling caused the avalanche to start.” Greenspan assures me that Black has never once mentioned anything other than battling to a full victory. When I later repeat Greenspan’s remarks to Breeden, he tells me, “I hope you laughed.” And he goes on, “An underlying sense I read into Conrad’s attitude is that these laws are quaint restraints on people who don’t have the vision to disregard them.”

I had spoken to Greenspan before Black so fervently decided to testify on his own behalf. Clearly Black’s testimony was a delicate subject, and the only point where I found Greenspan at a loss for words. When I asked him if Black would take the stand, there was a long pause and then: “I’ll leave that alone.” In their award-winning 2004 book, Wrong Way: The Fall of Conrad Black, Jacquie McNish and Sinclair Stewart report that Greenspan has made a deal with Black that every time Black, who is known for his rococo vocabulary, uses big words in the courtroom he will have to pay Greenspan—$50 for five-syllable words, $40 for four-syllable, $30 for three. “He talks like that when his shoes are off,” Greenspan informs me. “But also something goes with those words. There is an appearance of a pompous arrogance.”

Black took the Fifth Amendment in front of the S.E.C., in 2003, and many who saw him on the stand in another case, in Delaware, in 2004, after a lot of preparation with his expensive Sullivan & Cromwell attorneys, agreed that words failed him before corporate judge Leo Strine. In this case, Black was accused of trying to re-write the company’s bylaws, refusing to abide by a re-structuring agreement he had signed, and going behind the back of the board to try to sell off the London Telegraph to his own advantage. Strine issued a 134-page decision saying he had found Black “evasive and unreliable. His explanations of key events and of his own motivations do not have the ring of truth.” Greenspan admits that “that was a very serious turning point” in how Black was viewed. If Black bombed before an erudite judge in Delaware, what about tough Chicago, where juries, one native tells me, “resemble the riders on a Chicago Transit bus. Chicago is ethnic; it’s Irish, not English.”

Greenspan has chosen a colorful veteran Chicago defense attorney to be at his side during the trial, another Fast Eddie—Edward Genson, who, because of a neuromuscular condition, comes to court on an electric scooter. Upon news of his appointment, he was quoted in the Chicago papers as saying, “I’ve never represented a Lord.” That is an understatement. “Many of Eddie’s people are Mobbed-up, crooked people,” says well-known Chicago broadcaster and columnist Carol Marin. His last celebrity client was rhythm-and-blues singer R. Kelly, whom he defended against kiddie-porn charges.

Greenspan, who never betrays a trace of doubt about getting Black off, tells me, “I have found no smoking gun.” I wonder, though, what he considers David Radler. On September 20, 2005, Radler, the onetime chief operating officer of Hollinger and publisher of the Chicago Sun-Times, and Conrad Black’s closest business confidant and partner for 36 years, struck a plea bargain with Fitzgerald’s office and agreed to testify against Black.

Attack of the Germaphobe

In his 1993 autobiography, A Life in Progress, Conrad Black mentions David Radler 28 times. They met in 1969 as young conservative activists, and along with another young conservative, Peter White, they began buying Canadian newspapers. Radler quickly established himself with newspaper staffs as a cost-controlling, union-hating “human chain saw.” One reporter at the first paper the three men bought, the Sherbrooke Record, was fined two cents by Radler (as Black writes in A Life in Progress) “for wasting a sheet of paper” he had written his grievances on. The team seemed to have a winning formula. In Black’s words, “None of us could foresee how far this interesting partnership would lead, but when in less than two years, we started to rack up annual profits at a rate of over $150,000, we determined to expand in the newspaper business.” Black and Radler would take their company public in 1994.

For more than 13 years beginning in 1970, Black suffered paralyzing anxiety attacks, which caused him to go everywhere with a vomit bag in one pocket and Tums in another, but that did not keep him from traveling the world while Radler stayed home and minded the store. On the side, Radler actually always did run a store; in the 60s it was a native-handicrafts shop in Montreal, and later he had a jewelry business.

“Black spent every dime he ever had, and Radler still has his first nickel,” says Paul Healy, the former vice president of investor relations for Hollinger International. Headquarters for Black was an elegant Greek Revival building at 10 Toronto Street, in Toronto. Radler moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, where he still lives, and ran their far-flung interests from a nondescript building with a cardboard sign. Ironically, until recently they continued to own a number of community newspapers together, though they do not speak. Ken Whyte told me last winter, when Black and Radler had not yet begun to dissolve their business partnership, that people should not think Black is broke. “They have quite a profitable little company that makes at least $20 million a year. It’s got to be worth at least $100 to $200 million.” How much these assets are really worth, and the nature of the Black-Radler relationship, will clearly become an issue at the trial.

Black and Radler constructed their empire with a mind-boggling complexity of financial instruments that many people now believe threw off inquiring journalists, board members, and shareholders. They became known for their acumen, their photographic memories, and their ability to fight on several financial fronts at once—swooping in to buy properties such as the London Telegraph at distressed prices and turning a profit within a few years. In 1986, the year they bought the Telegraph, they were joined by J. A. “Jack” Boultbee, Black’s former personal-tax lawyer, now also under indictment, who became the executive vice president of Hollinger. He is “so bright as to be unfit for human consumption,” Ken Whyte told me. “Conrad has the closest thing to perfect recall for details of anyone I have ever met, but he still calls on Boultbee when he needs relevant details.”

As Black became more flamboyant, spending company money to purchase the antique Rolls-Royce, Radler kept a low profile. “If you come across as having lots of money,” he once told a subordinate, “people are going to ask you for something.” But Radler used the second jet—the planes cost Hollinger $23 million over a three-year period—and maintained an apartment at the Four Seasons in Chicago, paid for by the company, while he presided as publisher of the Chicago Sun-Times, from 1995 to 2003.

In a curious way, Radler also mimicked Black’s grandiosity but chose to make his name through supporting Jewish causes. He oversaw The Jerusalem Post after Hollinger bought it, in 1989, and he used company money to purchase medical equipment for the Herzog Hospital, in Israel. A wing of the hospital was named the Rona and David Radler Trauma Recovery Unit. Under his direction large donations from the Sun-Times and Jerusalem Post charitable funds were made to Haifa University, which conferred an honorary degree on Radler. In Ontario, he had Hollinger donate $168,000 to establish the Radler Business Wing at his alma mater, Queen’s University. To make the business run smoothly, his wife, Rona, was named the head of the Sun-Times’s charity, receiving a total of $126,000. Meanwhile, Black used company charity money to endow a wing at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children in his family’s name and to contribute to the pet causes of people on his board. Black and Radler never asked for approval of any of these donations from the board. The special committee says that, in addition to Black’s and Radler’s taking personal credit for donations made with Hollinger funds, “in return they often served on charity boards or attended lavish events.” In fact, at the Hollinger Inc. board meetings in Canada, Peter Munk says, “Barbara would always sit next to Marie-Josée, and they would chitchat about the next party.” Radler and Black apparently had few scruples about using money from the newspapers’ charitable trusts for highly unusual purposes. When the veteran columnist Carl Rowan was jettisoned from the Sun-Times after Black and Radler took over, he sued for ageism. According to John Cruickshank, formerly the editor and currently the publisher of that paper and others, part of Rowan’s $250,000 settlement was taken from the Sun-Times’s charity fund.

“We all tried to keep our distance from David,” Cruickshank says. “He is a very, very smart, deeply cynical guy who is completely committed to the bottom line.” Joycelyn Winnecke, former Sun-Times managing editor and now associate managing editor for national news at the Chicago Tribune, tells me, “I hated to see him come into the newsroom, not because I dreaded him, but because I wanted to keep him away from the staff. He seemed to enjoy agitating people.”

Lord and Lady Black rarely came to Chicago, but when they did, Barbara and Radler would reportedly bicker like biddies until Black called a halt, exclaiming, “All right, stop!” Executives also say that, behind Black’s back, Radler would make fun of his limousines, refer to him as Crossharbour (and to Barbara as Lady Very Crossharbour), and emphasize that “I’m not like that.” When Radler invited Sun-Times executives to lunch in his office—which opened onto a balcony where he sunned himself to maintain his perpetual tan—he would usually serve hot dogs.

He paid attention to the smallest detail. Once, to drive up the price for some of Hollinger’s papers, Radler, according to an associate, flew an employee to France to buy special French cigarettes. He then had someone smoke them down to stubs, which he left in ashtrays in the company conference room so that the people bidding would think they had foreign competition. He would come in on Saturdays, says Winnecke—who says she cut millions from the news budget at Radler’s direction—and would “personally go through stacks of invoices, complaining about toner costs. He had a calculator in his head.” At one point, to save $22,000 a year, he shut down the building’s escalator. Even as he bled the paper dry, his mantra was to not mess with “poor people” such as the janitors or with “the vets” who had been there more than 30 years. But, as he reportedly told one executive, “everybody else you can fuck with. Anybody who’s worth a shit isn’t here anymore because of what I have done to this company.” His management style, another executive told me, was to prey on people’s weaknesses. “He had something on almost every guy working for him.”

Though he was parsimonious in the newsroom, Radler had his charming side for those he favored. A devoted family man, he would interrupt important financial negotiations to take phone calls from his two daughters, one of whom worked at the law firm of Big Jim Thompson. He also gave stock options to certain reporters. I asked one of them why she had been so chosen. “Because I’m Jewish,” she says. “I’m already on third base. The Jews did better; he favored the Jews.” Ironically, at Christmastime, Radler expected to be showered with gifts by his staff. “He got the biggest kick out of amassing gifts,” Winnecke tells me. “He would say, ‘Come see how many I have now.’ He was like a little kid.”

According to a special-committee staffer, when the committee called to get certain files for its investigation, Radler was less than cooperative. Mark Kipnis, the Hollinger counsel now under indictment with Black, was Radler’s representative. The staffer tells me, “He’d say,’There is nothing you’d care to see in this pile.’ We wanted to be as diplomatic as we could, but there were things we wanted to see.” John Cruickshank says, “Whether [Radler] used people’s weaknesses, I don’t know. What I can say is he got some lovely people to do some bad things.” (Kipnis made all of his files available, including his personal files, his attorney Michael Swarz assured me. Radler’s attorney, Anton Valukas, says, “To my recollection he was fully cooperative with the special committee.”)

Before the special committee, Radler was a reluctant witness, saying on various occasions that he did not recall how certain questionable payments had accrued to his and Black’s benefit. The committee’s report cites “Black and Radler” hundreds of times, as though they were the same person: “Black and Radler made it their business to line their pockets at the expense of Hollinger almost every day in almost every way they could devise.… The Special Committee knows of few parallels to Black and Radler’s brand of self-righteous, and aggressive looting of Hollinger to the exclusion of all other concerns or interests, and irrespective of whether their actions were remotely fair to shareholders.”

Radler declined to be interviewed for this story. He is quoted in McNish and Stewart’s book, before his plea agreement, as calling the special committee’s report a “highly inaccurate and defamatory diatribe written more like a novel than a serious report,” and he notes that Hollinger International’s auditors, KPMG, had approved the various transactions that are in question.

In September 2005, Radler’s plea bargain was announced. Ken Whyte and other friends of Black’s told me that, though there had been a strain between the partners for a couple of years, Radler’s betrayal came as a blow to Black. “David was looking at most of his life in jail—seven counts at five years a count—and there was no indication that was the end. And he still may face charges in Canada,” John Cruickshank, who worked closely with Radler for three years, tells me. Also, since Radler is “deeply cynical,” in Cruickshank’s words, “he assumed if he didn’t do it, somebody else would do it to him. And he was profoundly scared of jail.” Radler, who is said to be a germaphobe, wouldn’t even swim in the Four Seasons pool. How would he survive in prison?

According to numerous attorneys I spoke with, Radler worked out quite a cozy deal with Fitzgerald. He agreed to serve 29 months in jail, and the U.S. government will allow him to serve his time in Canada, where there is an accelerated parole system. Radler must pay a $250,000 fine, and he has already paid back his share—$8.65 million—of the proceeds from the non-compete agreements. His plea bargain will remain contingent on how fully he cooperates with the prosecution. “David Radler will be a devastating witness,” former Hollinger executive Paul Healy assures me. “He has a mind like a steel trap, and he never threw away a scrap of paper.”

Meanwhile, Edward Greenspan says he cannot wait to have at Radler on the witness stand in order to discern which story is the real one—the one Radler told to the special committee, in which he seems to recall very little, or the one he told to the grand jury. “If he has done something wrong,” Black dispassionately told reporters when asked about Radler at his arraignment, “he should have to pay for it.” Black can try to distance himself, but Radler’s actions must weigh on him heavily. As one of Canada’s top political leaders tells me, “The center of everything here is David Radler—his testimony, the perception of him, the deal he took upon himself with Fitzgerald, and the cross-examination of him by Edward Greenspan. There in a nutshell is the entire future of Conrad Black.”

Radler’s testimony could also have an impact on Richard Perle, the only outside member of Hollinger International’s three-man executive committee (Black and Radler were the other two) from 1996 to 2003. Except for a few months of that time, Perle also served as the C.E.O. of Hollinger Digital, in what the special committee, which is suing him, calls an obvious conflict of interest. The committee’s report accuses Perle of “‘head-in-the-sand’ behavior that breaches a director’s duty of good faith and renders him liable for damages under Delaware law.” According to the committee, Perle has said he generally did not bother to read the papers that were passed along for him to sign, papers that are alleged to have cost Hollinger millions. Perle was also one of the beneficiaries of an unusual Hollinger Digital bonus plan, which handsomely awarded him and Black and other executives bonuses on investments that paid off, but which made no deductions for investment losses. (Digital’s investments generated $68 million in losses from 1996 to 2003.) Perle’s total compensation by Hollinger International from 1998 to 2003 was $5.4 million. While serving as chairman of the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board, Perle also set up Trireme Partners, a venture-capital fund focused on homeland security and defense, and he got a $2.5 million investment from Hollinger for Trireme, which was never reported to the audit committee. Both Black and Kissinger were on Trireme’s board. At one point Perle was even charging groceries to Hollinger. Perle chose not to provide a statement for this article, other than to tell me that the special committee’s report was “filled with inaccuracies.” So far, Perle’s legal fees exceed $4 million.

Hero Versus Pariah

If only as insurance against the possibility of conviction, it is not surprising that Lord Black is currently trying to get his Canadian citizenship back, with the help of an immigration lawyer. Should Black be found guilty in an American court and be sentenced to time behind bars, then theoretically he would have to serve his sentence in a tougher, U.S. prison. Canadian immigration experts, however, have stated that in all likelihood nothing will move forward until the criminal charges are dealt with. In any case, many Canadians will never forgive him for renouncing his homeland. Even Greenspan says, “My view is that I would not have done it.”

One day last year, I lunched at the Waspy Toronto Club, of which Black became a member on his 21st birthday. I was the only woman in the dining room. “They’re really snobby,” Hal Jackman, a prominent businessman and former lieutenant governor of Ontario, tells me about the members’ attitudes toward Black today. “They say, ‘We hope Conrad won’t embarrass us by coming in.'” Jackman used to be on the Hollinger Inc. board, but he quit, he says, because Black’s ego got in the way of sound business decisions and led him to buy properties such as The Jerusalem Post and the now defunct Canadian magazine Saturday Night. He adds, “He is not a natural chief executive; he should be in the academy or in your world.” Jackman, who hopes Black’s dilemma will help strengthen what he considers the weak securities regulatory system in Canada, echoes what others told me motivated them to serve on Hollinger’s board. “Conrad is entertaining, a person of extremes. I said to one guy I know on the board, ‘Why are you still hanging around? Nobody ever knows what he’s doing.’ My friend said, ‘It’s better than anything on TV!’ Conrad says things like ‘The last time I spoke to Shimon Peres … ‘ He remembers conversations you had three years ago—he knows where all the ships were in [the Battle of] Trafalgar.”

“Something I have never seen written about is the pattern in Conrad’s life going back to school days,” says his boyhood chum John Fraser, master of Massey College, at the University of Toronto. “One day he’s a hero, the next a pariah.” Fraser mentions the well-known story of Black’s being expelled from Upper Canada College, the prestigious boys’ school in Toronto, for selling exams. “For a 15-year-old it was a daring caper. He knew what the parents were worth, so he sold them on a rising scale. If you go through how he took over Argus [a major investment company; the widows of two of its founders endorsed Black initially but then changed their minds] and Hanna [the mining company, over which he received the consent decree in 1982], you see the same pattern of daring and maybe overreaching. His creative instincts are for acquisitions, not mergers.” The business atmosphere that Black grew up with was fairly lax—Canada is the only Western country except for Bosnia and Herzegovina that still does not have a national S.E.C.—and his company did not go public until 1994. “Conrad was enabled his entire career,” Jacquie McNish says, “by shareholders, by the media, by regulators. Many questions were raised about Black’s corporate moves for years. The media, as a result of litigation, was gun-shy. Anyone who interfered got served with a lawsuit.”

For many young Canadian conservatives, however, Black is a hero, particularly for founding the National Post newspaper in 1998 as a lively, right-leaning antidote to the traditional, liberal-dominated press. He lost more than $150 million and sold it in 2001. In an e-mail response to questions I posed, Black said he considers his most significant contributions to journalism to be “resuscitating the Daily Telegraph and making it the greatest newspaper franchise in Europe, and founding the National Post and giving Canada an alternative national newspaper and raising the quality of every newspaper I had anything directly to do with.”

“He does have some very loyal friends,” Rudyard Griffiths, one of the founders of the Toronto-based Dominion Institute, tells me. “Conrad—love him or hate him—manages to stir up the debate in the country about what Canada means and where it is going.” These younger friends credit him not only with shifting the paradigm of the political debate and helping contribute to the election of a conservative prime minister for the first time in 12 years but also with forcing the competition—The Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star—to get better. Adam Daifallah, 27, who co-authored Rescuing Canada’s Right: Blueprint for a Conservative Revolution, tells me, “Black made it socially acceptable to be a conservative in the media. Before, it was just unheard of.” Edward Greenspan says that a number of law students have volunteered to help him prepare Black’s defense and that he has begun giving them documents to read. “Conrad does not admit he’s done anything wrong,” Hal Jackman says. “He thinks it will all come out great in the end. He always had a sense of entitlement as a proprietor.”

The Cleopatra of Kensington

Ownership of a major conservative daily in London conferred entrée to the best tables and most discriminating salons. Even Prince Charles was interested in meeting the new owner of the Telegraph when Black arrived, in 1989. The Prince “was very concerned about his P.R.,” says Peter Munk, who introduced them. Black knew every branch, every twig of the Prince’s family tree and recited “every ancestor, every battle,” according to Munk. “I don’t know if Conrad charmed him—he lectured him. Conrad knows everything, and he wanted to make sure Prince Charles understood that.”

Black arrived in England with his first wife, Shirley, the mother of his three children, who are now in their 20s. By 1991, however, Shirley, who had changed her name to Joanna, was back in Canada. The marriage crumbled when she fell in love with—and later wed—a Catholic priest.

Meanwhile, Barbara Amiel entered the picture. “Conrad was never a sexual being,” a longtime acquaintance of his says. “Then he met Barbara. Welcome to the N.F.L.!”

Most disconcerting for those who dealt with Barbara were her sudden mood swings. “One day she’d fix you with the big laser beam, the big smile, big charm,” a London friend of the Blacks’ tells me. “But she turned it on and off. When you got it upon you, it was very bright. When it was not upon you, it was very dark.” Charles Moore adds, “One day she is kind, warm, helpful. Then she’ll turn her head around and barely look at you. In social relations, she was definitely giving orders to him—it was not the other way around.”

Barbara’s friends say that she is totally misunderstood. Amiel suffers from an uncommon autoimmune disease called dermatomyositis. According to Dr. Lawrence Tierney, senior editor of Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment, 2006, “Patients typically are unable to gain appropriate strength, especially in the thighs and upper arms, so symptoms include inability to climb stairs, comb hair, or even rise from a sitting position without help. As it is an inflammatory condition relating to the immune overactivity, persons often feel poorly as well, with mild fever, fatigue, and inability to concentrate. Treatment includes suppression of immune activity with steroid hormones. These latter are well known to cause a variety of side effects, including central-nervous-system abnormalities simulating various mental illnesses.” In his highly regarded biography, Shades of Black, Richard Siklos reports that Amiel claimed that blood treatments took her out of commission several times a year. “People in London and everywhere are very keen to laugh at or dump on rich, powerful, good-looking women who make the most of their riches and powerful positions,” says Miriam Gross, the former literary editor of The Sunday Telegraph and a close friend of Amiel’s. “She’s a very serious columnist, more serious than many in England. She is very kind to her sister, and she is very good with illness—she certainly knows illness!” The historian Andrew Roberts says, “There are unbelievable buckets of envy. Envy is the definitive characteristic of London newspapers.” The Blacks’ parties, Roberts tells me, were a heady combination of “good champagne, beautiful women, powerful men, witty repartee—it’s what we’d all do if we were rich enough.”

Amiel herself has recently addressed the issue of the burdens of high society, using her column to offer a stirring defense of Marie Antoinette. The pretext was the Sofia Coppola movie about the French queen; the subtext was obviously her own life. “The one fatal thing all so-called Marie Antoinettes share with the real one,” Amiel wrote, “is blindness to the dangers of any social generosity they may display.” In the same column, she observed that women and men are judged very differently: “This is not gender bias, only recognition that men usually earn, cobble together or steal the money they spend. Women very often don’t. They spend the money that some man cobbles or steals for them.”

“I don’t even know the woman I’m reading about—some dreadful slattern,” Amiel’s friend Leoni Freda tells me. The irony, according to Freda, is that Barbara did not really even like the parties, and soon tired of having to tend to the great names and run the grand houses. “I think she’s unbelievably shy,” Freda says. “She was tortured” many times during those parties and would “disappear down staff stairs hidden in the paneling,” taking a glass of vodka with her. “‘Do you think I can have this [party] without a drink?’ she said, and it’s the only time she really drank.” Another writer, Sarah Sands, paints a different picture, describing her after a party holding court in her boudoir, “where she lay on cushions surrounded by her women friends … Kensington’s Cleopatra.”

Apparently the grand lifestyle became so overwhelming that, when something did not fit the picture perfectly or became difficult to cope with, it was simply removed. Jack Valenti, the former head of the Motion Picture Association of America, tells me that he is still astonished and hurt at the way he was treated one night at the Blacks’: “I was invited for dinner, and called several days ahead to say my plane would be landing at eight p.m. and I would pick up a family friend and come directly to the dinner a little late.” When Valenti and his friend arrived, however, they were taken not to the dining room but to a dark waiting room downstairs, where they sat for more than half an hour without even being offered a drink. Only when the dinner was over did Valenti encounter his hosts. “They behaved as if nothing had happened, and made no apologies,” his friend says.

Brian Stewart feels that Barbara was not at fault. “He’s the one most driven to create this world,” Stewart tells me. “The rich-and-famous functions could help his publications—that’s the way a publisher should act. I never bought Barbara as the reason for the ‘Versailles-ization’ of their existence.” Rather, according to Stewart, “he is so enamored of Barbara, he loved to show her off. His pride in Barbara is absolutely intense. He found a soul mate.”

Whatever their misgivings about Black, almost all of the people I spoke with who had worked for him at the Telegraph agreed with Charles Moore, who considered him a “fantastic proprietor” because “he liked a good paper.” Black loved to discuss world affairs with his editors. “I got into scrapes taking on powerful people, and he always stood up for me and took the flak,” says Dominic Lawson, who was the editor of The Sunday Telegraph. But no matter how well the paper did, the editorial budgets did not increase; in fact, they were cut. “It was slightly soul-destroying,” Con Coughlin says. The staff suspected that the National Post, in Canada, was bleeding a lot of the profit, but no one really knew. “Boultbee and Radler were very secretive and not interested in delegating,” Jeremy Deedes tells me. “They would only tell other people what they needed to know. It was a completely alien culture.”

More than anything, those who worked closely with Black in London came to feel that their boss was not paying enough attention to the business. “There is no question, his eye came off the ball. If I put my finger on when it happened, it was when he started to write the Roosevelt book,” says Deedes. Moore agrees: “Conrad became more detached. He had a slight detachment from reality in general. All of these great figures follow their own star, and he’d always done that. But in retrospect I see that Conrad never really had a strategy for his empire. He had tactics.” Jeremy Deedes adds, “He had no grand vision. It became largely a game of manipulating money, wheeling and dealing.” According to Moore, “Conrad got seduced by all the fun you get by being the owner—he was so interested in politics, meeting famous people, flying all over.” The main thing Black seemed to forget was that, after 1994, when the company went public, he was no longer the owner.

The “Holy War” Option

Times have changed in England for Lord and Lady Black since their heyday. When they returned to London in July 2005—after the special-committee report had come out but before Black was indicted—the London papers had a field day. One ran the headline return of the pariah, and certain doors were closed to them. “I think Conrad feels the Jews and Catholics have been very loyal and the Episcopalians less so,” Dominic Lawson says. “The Jews and Catholics are more accustomed to persecution.” It was not as if the Blacks were not entertained at all; Lady Annabel Goldsmith, Lord Weidenfeld, Princess Michael of Kent, and Drue Heinz all hosted them. “You don’t just turn against friends when adversity hits them,” Goldsmith says. However, their once close friends Elton John, Jacob Rothschild, and Lord Weidenfeld all declined to talk to me about the Blacks. Margaret Thatcher has issued a strong statement: “Lady Thatcher always had a good personal relationship with Conrad Black. She does not cut and run just because someone gets into difficulties. Conrad is innocent until proven guilty. Lady Thatcher will let the courts decide.”

Apparently Amiel felt the poisoned atmosphere most keenly. “She thinks that had Conrad approached things differently in London this experience in London society would have been a lot different,” Ken Whyte tells me. “She thinks it’s a big mistake to care about how you are received in this circle, because if they notice you care to be accepted, they’re sure not to accept you.” In David Metcalfe’s words, “You entertain a lot, you’ve got a big flat, you give big dinners, you have lots of money, then it all goes away and so do the people.” Amiel may get her revenge, however. She is said to be furiously writing her memoirs.

In any event, London was only one slice of Black’s world, and not necessarily the one that mattered most. “I was always puzzled by a real oddity about Conrad,” Charles Moore says. “He was indeed very important in London, and he had the capacity to be very important in Washington. What he wanted to be was important in New York. New York is not political, it’s financial, and he and Barbara decided to be in the society of quite stupendously rich people.”

“No Canadian in history has ever loved America like Conrad,” Brian Stewart says. But New York was Black’s downfall. There the jury-rigged empire he had constructed to satisfy his need for cash and to service the company’s debt began to be scrutinized. Beginning in the mid-90s, the Blacks set out to conquer the Big Apple the way they had conquered London, attempting now to keep up with billionaires instead of millionaires and to penetrate the innermost sanctums of high society. And New Yorkers tripped all over themselves to make the newly minted Lord and Lady Black welcome. Barbara reportedly took her old paramour George Weidenfeld’s advice and concentrated on the ladies, particularly Annette de la Renta, the wife of fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, Mercedes Bass, the wife of financier Sid Bass, and Jayne Wrightsman. “Will you take me shopping?” she would ask her fashionable friends. She and her closets were featured in Vogue, while Conrad ingratiated himself with members of the Council on Foreign Relations—a guaranteed stepping-stone to gravitas. In Manhattan’s celebrity melting pot, under the patronage of the Kissingers, the Blacks fit right in. “I was present at her 60th birthday,” a onetime close friend of the couple’s says, “and she had herself seated next to Donald Trump. That told me everything.”

Their Park Avenue apartment, bought by the company and now part of the dispute, featured a custom-made steel door between the dining room and the pantry to keep out the kitchen noise, and plaster-of-Paris plates of U.S. presidents on the dining-room walls. Though the Blacks rarely entertained at home, between 1997 and 2003 Hollinger paid $1.4 million in wages to their servants in New York and elsewhere. The Blacks were out every night, and Barbara’s women friends often commented on how brave she was to go to all those dinner parties when her illness sometimes made it hard even to get up from the table. “She is making such an effort,” they would say. Black dazzled the upper crust with his vast stores of random knowledge, which exerted an unpredictable appeal. “I always look forward to sitting next to him,” Judy Taubman, the wife of board member Alfred Taubman, tells me. “He can recite entire chapters of Cardinal Newman’s writings.”

The Blacks also purchased a 17,000-square-foot mansion in Palm Beach, where they posed for this magazine in the winter of 2003, with Barbara kneeling on the lawn beside the seated press baron. By then, however, the dénouement of their story had been set in motion by Hollinger investors such as Tweedy, Browne, which demanded that the board take action and alerted the S.E.C. The first blow came in October 2001, when Laura Jereski, a former Wall Street Journal reporter working as an analyst for Tweedy, Browne, questioned Hollinger’s non-compete payments and exorbitant management fees, and pointed out the coinciding lack of growth in the company’s share price. Other institutional investors, such as Cardinal Capital Management, in Connecticut, also expressed concern. Cardinal made the first overture to Herbert Denton, of Providence Capital Inc., an outspoken shareholder activist whose firm uncovered more alleged improprieties by researching Hollinger International’s public documents. In the spring of 2003, after getting no satisfactory response from Black nor seeing any action from the board for 19 months, Tweedy, Browne, using Denton’s research, filed a 13D complaint with the S.E.C., which included a demand that Hollinger International’s board explain the non-compete payments. “What we did was to write a bill of particulars of the depth, frequency, and variety of suspected malfeasances led by the star witness, because 100 percent of the non-competes went to the management and not to the company,” Denton says. “We saw $73 million diverted into Conrad’s pocket, yet the signature on the contract was the corporation and he signed it as C.E.O.”

Alarm bells started sounding. “When you join a board, you assume they are not engaging in massive fraud,” an insider tells me. “And Conrad was seen as somebody who knew the newspaper business—how to run it and run it properly. The people he had assembled were the people he liked to hang out with—it established a real sense of a certain legitimacy.” In addition, Black’s overpowering personality seemed to make everyone defer to him, especially in regard to his ultimate control of the company. Because of a dual voting structure of two different classes of shares, Black, who owned 30 percent of Hollinger International’s equity, was able to control over 70 percent of the company’s voting interests. He allegedly abused this cushy arrangement by diverting nearly $200 million in excessive management fees through his holding company, Ravelston, to his and his associates’ own pockets. Someone close to the board told me, “When he listed in the U.S., he wanted to ride up the stock with the shareholders, and he was going to make money and everybody would make money.”

In the wake of the 13D filing, however, three new board members were to be installed on the recently formed special committee, and Richard Breeden, who charges $800 an hour, was hired, assisted by a legal team from O’Melveny & Myers. For more than 30 years Black and Radler had gotten their way, Breeden says. “In their careers they had never, ever encountered anyone who would pursue facts until you got to the bottom. It induced great confidence on their part.” In October 2003 the investigation turned up the shocking revelation that the specific details of the non-competes had never been disclosed to the board, while other non-competes allegedly had been totally mischaracterized. “Your first instinct is: there has got to be some innocent explanation, because it looks like a crime,” one of the investigating team tells me. “I remember sitting in Breeden’s office being stunned by what I saw,” says Raymond Seitz, former U.S. ambassador to Great Britain and a member of the special committee. “I think they thought they were onto a good thing, a great way to siphon off money.”

As the mystery unfolded, Black was given many chances to control the damage, but he refused. Today the fancy New York friends who fêted the Blacks back then sit around their dinner tables speculating about what kind of jail sentence he might get, if convicted. But in the beginning even the board felt that an accommodation could be made regarding the Roosevelt papers and the jets, and that the whole issue would blow over quickly. “He could have settled,” a member of the legal team says, “but he wanted to wage a holy war.” Breeden tells me that Black could have quickly paid back what he owed, resigned as C.E.O., and remained as chairman, adding, “Would he be where he is today? I wouldn’t think so.” Robert Pirie, a lawyer and bibliophile who met Black when Pirie was affiliated with the Rothschild banking group and Black was a client, urged him on several occasions to settle, telling him, “These guys are too tough.” According to Pirie, Black would say either “I have done nothing wrong—these people are scoundrels” or “Everything is under control.” Once, Pirie says, driving back from the Kissingers’ country home in Connecticut with Black, he told him, “Conrad, you need a Dutch uncle. I am going to be your Dutch uncle.” He basically urged Black to quit suing people. “Even if you’re innocent, it looks foolish. This is a case where you shut up, hunker down, and cut a deal.” In the summer of 2004, after Black had lost almost everything, Pirie recalls, “we sat in my garden till three a.m., smoking cigars and drinking brandy. I still couldn’t get through.” The next day Pirie saw Black in his shirtsleeves on Park Avenue, “looking lost” and trying to hail a cab. “For the first time in years Conrad is alone on a street in New York. That to me sums up the collapse of Conrad.” Pirie would later tell me, “I find him mystifying. All of his friends—nobody understands why he didn’t fix this three years ago. Look, he’s not a mass murderer. At this point it’s tragic, and a little more tragic because it’s of his own making.”

The Consolations of History

Today, even the Hollinger name is gone. Black’s once powerful newspaper empire is now known as the Sun-Times Media Group, Inc. The share price has declined 31 percent in the last six months, and no dividend was issued for the last quarter of 2006. The old Hollinger International and Hollinger Inc. are mired in cannibalistic, internecine lawsuits. Investigators are still trying to ascertain whether Black squirreled money away in foreign places. Black’s attorney, Edward Greenspan, says, “We’re not hiding assets at all. They have all the information.” And he adds, “The person who knows exactly what they’re worth is their star witness—David Radler.” As for those investors who hoped the indictment would clear the way for the sale of the remaining assets, which so many were confidently predicting a year ago—well, they are still waiting. (“The natives are getting restless,” says Chris Browne, of Tweedy, Browne.) Now a self-proclaimed freedom fighter, Black last fall went on the offensive. He began speaking—performing—in public once again, using words like “fissiparous” (another $40 for Greenspan) from the podium and wowing Establishment audiences in Canada who are meant to feel that he is being picked on by Uncle Sam. He and Barbara Amiel both have regular columns, hers in Maclean’s magazine, his in the National Post (where his Web biography says that he considers the charges against him “unfounded and scurrilous,” and that he “looks forward to a complete acquittal and vindication and the full resumption of his financial career”). Meanwhile, in the U.S., the legal battles continue over who has the right to the Blacks’ many acquisitions. The antique Rolls has been auctioned off, but the $2.6 million 26-carat-diamond ring Black bought for his wife soon after receiving an $11 million non-compete payment, in 2000, is the subject of a U.S. restraining order; it is also property, along with other jewelry and antiques, that Canadian litigants want to acquire. Black’s attorneys maintain that neither can have the Black diamond, because it belongs to her, not to him. According to the London Daily Mail, Barbara recently went on one of those former-life shopping sprees in Toronto, buying $25,000 worth of clothes, bags, and shoes in a single excursion. The next day, the Daily Mail reported that every bit of it was returned, without a word of explanation.

Conrad Black remains in residence at the old family home, the very place he grew up, behind that weeping-willow tree and under the watchful eye of the faithful Berner. “I have no aspiration to any public life anywhere after repulsing this attempted destruction of me,” he wrote in response to a question I had e-mailed. “I will be ready for a quieter life. I would not presume to claim that I confer any importance and benefit on ‘the larger society,’ other than possibly, to a slight extent, as a historian, and through whatever modest charitable contributions I can make. I will return to the House of Lords, but that is hardly a position of great influence in itself.” Conrad Black is now concentrating on writing his next book, about the tragedy of Richard Nixon, another man who didn’t understand, until too late.

No Comments