In 1215, King John allegedly spent the night before signing the Magna Carta at Duncroft, a manor about 20 miles west of London. By the 1970s, Duncroft had become an “approved school,” a stately home with bars on the windows for intelligent wayward girls. It was visited often by the BBC’s radio and TV star Jimmy Savile, Britain’s greatest pedophile. Growing up, BBC producer Meirion Jones would visit Duncroft, where his aunt was the headmistress, and he would witness Savile, the flamboyant M.C. of the music show Top of the Pops, alight from his Rolls-Royce proffering cigarettes, rides, and invitations to the BBC studios in London, where, it is now believed, he violated dozens of under-age girls—as well as boys—in his dressing room. “My parents would say to my aunt, ‘What are you doing letting a 50-year-old man take a bunch of under-age girls in his car?’ And my aunt would say, ‘Oh, he’s a friend of the school.’ ” (Jones’s aunt has recently said she had no idea Savile was a predatory pedophile.)

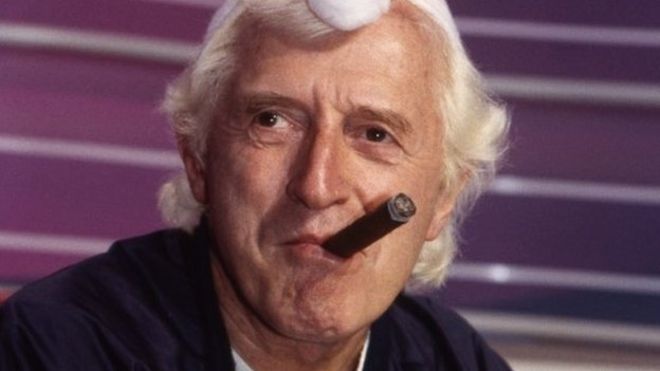

When Savile died, on October 29, 2011, at the age of 84, having been knighted by the Queen as well as the Pope, he was one of Britain’s most famous personalities, a combination of Dick Clark, Johnny Carson, and Wolfman Jack. The self-proclaimed creator of the first disco, he claimed to be the first D.J. to play records for money, in rough dance halls in Leeds and Manchester as far back as the 40s and 50s. In the early 60s, he counted among his friends the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Savile became so renowned for his charity work that he was literally given the keys to several hospitals and institutions, where he had his own rooms and volunteered as a porter and administrator, all the while cunningly waiting for chances to pounce on ill and vulnerable girls. He was proud of spending New Year’s Eve with Margaret and Denis Thatcher by the fire at Chequers, the British prime minister’s country house, and of acting as a go-between when Diana and Charles’s marriage was falling apart. A senior Health Service official known to one BBC staffer remembers once in the 80s being called to Highgrove House, where Prince Charles introduced everyone to “my health adviser, Jimmy Savile.” Dan Davies, Savile’s biographer, told me, “He was a very serious confidant to the heir of the throne up until Charles got together with Camilla. Then his influence waned.”

In his narcissistic 1974 autobiography, Love Is an Uphill Thing, Savile recounts a scruffy, almost Dickensian childhood as the youngest of seven in a Catholic family in Leeds, where he worked in the mines, and where his mother, nicknamed the Duchess, was the only true love of his life. On the first page he boasts that as a baby he once peed into his grandmother’s eye, adding, “I have continued to pee on the Establishment ever since with similar success.” The book is riddled with sexual braggadocio: “Were I to tell all, no one would believe it, plus I’d have to take up residence in some inaccessible Himalayan village.”

The BBC made him a star, though his outrageous style was in striking contrast to the network’s high-minded tweed-think, and today most there claim that he was never their kind. “Brash figures like Savile were aggressively anti-intellectual, childishly anti-political, anti-everything the BBC was concerned about,” says Jeremy Paxman, the anchor of Newsnight, the current-affairs program. “The managerial class was scared of them, and they were left to get on with it. So nobody really knew, and didn’t want to know.” Meanwhile, generations of English children were mesmerized by Savile’s show Jim’ll Fix It. They would write in their wishes, and he would have them appear with him on-air, where he would grant those wishes. One of the boys, then nine, now says he was assaulted in Savile’s dressing room. (According to the latest police report, 18 percent of Savile’s known victims were male.)

It’s not as if he didn’t leave clues. Savile, who could be threatening and quite litigious, recounts in his book an incident when he was warned by the police that there was a runaway girl in his area. He informed them that he would turn her in only if he was allowed to spend the night with her, “as my reward.” She soon appeared, and he blithely marched her into the police station late the next morning, where, he writes, “she was willingly presented to an astounded lady of the law. The officeress was dissuaded from bringing charges against me by her colleagues, for it was well known that were I to go I would probably take half the station with me.” (Savile regularly hosted coffees for chief constables and other officials.)

Talking to esteemed BBC veterans, one frequently hears the argument that the times were so different at the height of Savile’s fame, in the 60s and 70s—when rock stars and groupies were constantly thrown together, no age questions asked. A veteran BBC filmmaker told me the BBC itself “was a hotbed of repressed sexuality.” He recounted the tale of an editor of the current-affairs program Panorama and a female staffer encountered in flagrante across the editor’s desk one night by a fireman. “Don’t you even knock when you come in?” the editor asked. “I did knock, sir,” the fireman replied, “but you was knockin’ rather harder.”

Given England’s strict libel laws, Meirion Jones knew that he would have to wait until Savile’s death to act on years of rumors about the man’s sexual proclivities, indulged right under the noses of, or with the complicity of, the BBC, which so far denies having ever received any complaints about Savile during his 30-plus years of employment. Today, however, the exploding list of inquiries by the police and other institutions—more than 400 people so far have come forward to report sexual assaults by Savile—has thrown the BBC into turmoil, deeply embarrassed its hierarchy, contributed to the resignation of one director general, and cost British taxpayers millions of pounds for investigations. (One hospital has even investigated rumors of necrophilia.) Yet the public still does not know exactly why the BBC halted the broadcast of an exposé of the late Savile, prepared by Jones and correspondent Liz MacKean for Newsnight at the same time the network’s entertainment division was planning tribute shows to the star, which did run, at Christmastime in 2011. Both the exposé and the tributes had been planned for the BBC’s coming schedule, and the exposé was flagged on the Managed Risk Programmes List to alert all divisions that something that might affect the organization’s reputation was coming. Then the exposé was abruptly removed. According to the Pollard Review, the inquiry subsequently set up by the BBC to get to the bottom of what happened, deputy news director Steve Mitchell, who did the removing, can provide no explanation. Neither he nor Peter Rippon, the editor of Newsnight, who had put the exposé up on the scheduling board in his office, remembers a purported phone conversation they had the day before Rippon suddenly did a U-turn on Jones and MacKean and raised the bar on what it would take to get the exposé on the air. “You had two trains running simultaneously down the tracks,” explains Jones. “One was the Jimmy-Savile-is-a-pedophile train, and the other was the Christmas-tribute train.” The pedophile train had the brakes put on it November 30, a week before its proposed broadcast, but the Savile tributes ran on time.

Ironically, the tribute shows were presented in lieu of a formal memorial program, which might have proved to be too dicey to run. Almost a year and a half before Savile died, an e-mail unearthed in the Pollard Review was sent from a BBC executive who had worked with Savile years before to George Entwistle, who then had the Orwellian title of “controller of knowledge commissioning” but who later became the director general of the BBC for 54 days before he was forced to resign, because of what Savile had wrought. The e-mail stated, “I’d feel v queasy about an obit. I saw the real truth!!!” The day after Savile’s death, the executive sent another e-mail to another department, saying, “We decided that the dark side to Jim (I worked with him for 10 years) would make it impossible to make an honest film that could be shown close to [his] death. But maybe one could be made for later.”

In fact, 10 months later the rival, independent network ITV scored a huge ratings success after Mark Williams-Thomas, a former police officer in child protection who had worked with both networks, took the BBC’s original material with permission and expanded on it. Williams-Thomas’s program ran on October 3, 2012. The Guardian called it “one of the most talked-about shows of recent times” and it generated page-one headlines that seriously called into question the BBC’s decision to drop the Newsnight exposé. It included interviews with five female victims and a former BBC employee who had seen Savile kissing an adolescent girl in his BBC dressing room, and it drew attention to a dropped police investigation—one of several, it turns out—during Savile’s lifetime. “Clearly people either saw or turned a blind eye to young girls going in and out of his dressing room,” Williams-Thomas told me. “I find it astonishing that at no stage anyone would make a formal complaint.”

In September, three weeks prior to airing the program, ITV sent a series of questions to the BBC, asking for an explanation as to why Newsnight had chosen not to run the story. That sent the BBC scrambling. Peter Rippon posted to the BBC editors’ blog to respond to all the criticism in the press—a post that contained significant errors. He indicated the story had begun as an investigation into why the police had stopped their investigation of Savile, after a “key witness” told the BBC that the police dropped the case because Savile was too old. When the Crown Prosecution Service countered that the Savile investigation had been dropped due to lack of evidence, Rippon said, he had concluded that there was no story. In fact, that is not at all what happened.

The Newsnight program had begun as an investigation of Savile as a pedophile and abuser. Rippon suddenly made the dropped police investigation the issue after his purported phone call with Steve Mitchell, even telling Jones and MacKean, “I can’t go to the wall on this one.” Nevertheless, several major interviews were given by BBC executives, including Lord Patten, the head of the BBC’s governing body, the BBC Trust, who maintained the dropped-police-investigation line. Moreover, BBC management allowed the flawed blog to stand uncorrected for three weeks. The BBC was finally forced to correct it because of questions from the station’s own investigative program Panorama, which often competed with Newsnight, and was poised to air interviews with both Meirion Jones and Liz MacKean, who totally contradicted their boss. By that time, October 22, anyone in the line of fire further up the ponderous management structure of the BBC, such as Mitchell’s boss, Helen Boaden, director of news, whose job included telling Entwistle about the possible Newsnight story on Savile in the first place, had already been able to sidestep direct scrutiny by the media because Entwistle had called on Nick Pollard, the former head of Rupert Murdoch’s Sky News, to commence his inquiry. “It’s hugely convenient, because they don’t have to field any questions,” says Miles Goslett, a freelance journalist who was the first to seriously pursue the story.

Newsnight, meanwhile, itching to prove it still had all its moxie, contracted out what became a totally specious exposé, which truly tarnished its once sterling reputation. The Newsnight show that aired November 2, 2012, alleged child molestation in North Wales in the 70s by a former senior Tory figure whom it did not name but whose identity—Lord McAlpine, former treasurer of the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher—was tweeted thousands of times through “jigsaw identification.” The BBC lawyers and the show’s temporary supervisors had evidently not considered the implications of social media.

Alistair McAlpine, an author and a collector, revealed that he had never been contacted by the BBC, and his photo had never been shown to the accuser, who later declared that McAlpine was not the man who assaulted him, and apologized. Once again the BBC looked absurd, particularly since the whole issue of this mistaken identity had already been resolved in a 1997 investigation in Wales. In addition, the BBC had to pay McAlpine $293,000 in damages, plus legal costs. Several days after the spurious broadcast, Phillip Schofield, host of an ITV morning “couch show,” thrust a list of purported pedophiles at his guest, Prime Minister David Cameron, demanding to know what the government was going to do about it. For a split second, McAlpine’s name could apparently be glimpsed on camera, so ITV was then also sued by the lord, who collected another $200,000 in damages, plus costs.

Adding to the general chaos and mystery was the role played by former BBC director general Mark Thompson, who held that position until mid-September 2012. Despite press reports about the Savile scandal dating back to January 2012, including a detailed Oldie magazine article by Miles Goslett, Thompson has consistently claimed that he knew nothing of the swirling controversy of the Newsnight tributes fiasco until shortly before the ITV program aired, in October, after he had left. However, Goslett had made a Freedom of Information Act request to the BBC in April and called Thompson’s office in May. On September 6, in response to a series of specific written questions posed by the London Sunday Times Magazine probing into what Thompson knew about Savile and when, a letter was drafted on Thompson’s behalf by outside lawyers—not BBC lawyers—threatening libel action if The Sunday Times printed a story suggesting an intentional cover-up. Thompson claims never to have read the letter, which one London legal observer finds “inconceivable. If he approved and hadn’t read it, he’s just as culpable.” Today, Thompson is the newly installed C.E.O. of The New York Times, which has been compelled to report on his “evolving” views of what he remembers. For all concerned, this story just keeps growing, like Topsy.

‘The manure had been spread,” Athena McAlpine, the vivacious, much younger wife of Lord McAlpine, said of the garden her husband had been going to plant with prized David Austin roses given him for his 70th birthday. But the libel suits intervened. As we breakfasted one Sunday at the Ritz, in London, the couple explained the bizarre way their lives had become entangled with the toxic tweets as a result of the BBC broadcast. They had made Lord McAlpine a pariah and led to his declaration that he was planning to sue every single person who had falsely tweeted about him. That seemed most improbable in view of how removed the McAlpines are from the scene of battle. They live in a 500-year-old former monastery in a small village in southern Italy, without TV, newspapers, or—for him—the Internet. Athena keeps the monastery as a hotel but does not advertise for guests. She says of her husband, “All he does is garden. He wakes up at five A.M. and goes to the garden. I am a garden widow.” They had been planning a trip to Switzerland to see a collection of Indian bronzes, but the trip turned out to be to their lawyer in London. After two major heart bypass surgeries, one of which paralyzed a vocal cord, which makes it difficult for him to speak above a whisper, Baron McAlpine of West Green had deliberately absented himself from public life. He told me, “The oddest thing about the whole scenario is that we’ve almost elected to live outside the loop.”

Last November 2, however, he recalled, “I got a call from a journalist who said I was going to be named that night on Newsnight. I said, ‘Well, if they do that, I’ll sue them.’ I was quite flippant about it, and then I began to think, It’s a criminal affair, one of the worst criminal offenses. My wife’s business will be destroyed.” He said that Michael Crick, a political correspondent for Channel 4 News in Britain, “rang back later and asked if Newsnight had contacted me. I said no. Then he contacted me again and said it’s very unusual [not to be contacted]. Then he said, ‘Well, it’s too late now. It’s five P.M.’ Then the Telegraph rang. I told them I didn’t know anything about it—if it’s true, I’ll sue. Then it hit the Twitter. It went absolutely mad.”

Newsnight, short on staff, with its usual chain of command sidelined by the Pollard inquiry, had turned to a reporter from the small, independent Bureau of Investigative Journalism (B.I.J.) to mount the program that falsely incriminated Lord McAlpine. Acting editor Liz Gibbons had worked with the B.I.J. before and evidently felt she could trust it. The morning before the broadcast, however, Iain Overton, B.I.J.’s founding editor, unfortunately tweeted, “If all goes well we’ve got a Newsnight out tonight about a very senior political figure who is a paedophile.” Michael Crick cautioned in a later tweet, “‘Senior political figure’ due to be accused tonight by BBC of being paedophile denies allegations + tells me he’ll issue libel writ agst BBC.” Despite the warning, BBC lawyers evidently felt protected by not naming the accused. Soon thousands of people took up the tweets, and within 24 hours Lord McAlpine was being photographed by paparazzi gathered outside the monastery. One of those who tweeted was Sally Bercow, the tall, glamorous wife of House of Commons speaker John Bercow: “Why is Lord McAlpine trending? *innocent face*”.

That really rankled the McAlpines. Sally Bercow had previously posed for a magazine profile portrait in nothing but a bedsheet in a window in the vicinity of Big Ben. She became part of the cast of Celebrity Big Brother, a British reality series, “and she was the first one kicked out,” sniffed Athena McAlpine. The McAlpines filed a libel suit against Sally Bercow. Athena doesn’t have much truck with Phillip Schofield, the TV host who showed David Cameron the list of pedophiles with her husband’s name on it, either. “He began in children’s television with his thumb stuck up a glove puppet.”

Lord McAlpine, who claims that generally the BBC is “fantastic,” was determined to bring Twitter to heel. He announced a Web site where those with fewer than 500 followers who tweeted falsely about him could register, including a box asking, “Have you apologised to Lord McAlpine?” Those who filled out the form were also asked to make a small contribution to a BBC children’s fund, for he was not out to bankrupt ordinary people. Nearly 300 have done so. “It’s like the Black Death. You’re standing there, and one day later you say, My God, the world hates me,” Lord McAlpine said. “You used to be able to say, Today’s news, tomorrow’s fish-and-chips wrap, but with the Internet it never goes away.” Athena added, “These people are journalists, but they just don’t know it, and they are not subject to an editor. They are not subject to fact-checking.” Lord McAlpine’s lawyer, Andrew Reid, concurred: “If you go to a social-media board like this, there must be a mechanism to clear the board, to take [a libel] down immediately rather than let it pervade.” He added, “All social media does is allow people to operate in a cowardly fashion in the ether.”

The McAlpines feel strongly that they are victims of something more sinister and subtle. “The subtext is actually more interesting than the actual act,” Athena told me. Explaining why her husband ended up as the target, she said while ticking off on her fingers, “He was a Tory, a toff, and, worst of all, a Thatcherite!” Lord McAlpine added, “I cannot imagine the hostility that exists towards this woman [Thatcher] even today. In Billy Elliot there are lyrics that even say, ‘One day closer to her death’ .” Athena cited numerous pictures in the press showing Savile with Thatcher and with Prince Charles in kilts. “There’s an agenda,” she said.

There is a long-standing enmity between Lord McAlpine and Lord Patten, the non-Thatcherite, conservative head of the BBC Trust and adviser or director of at least a half dozen other institutions, who was described to me as “an ornament of the British establishment.” According to the Daily Mail last November 11, “In McAlpine’s 1997 memoirs Once a Jolly Bagman, he recalls asking Patten to lunch at The Dorchester hotel shortly after becoming treasurer. ‘I can remember him tucking into a plate of oysters,’ he wrote, ‘his blond forelock falling forward, hiding both his face and the oyster that he was eating.’ McAlpine found this significant. ‘You can always tell the character of a man when he eats oysters, and I marked Patten down as greedy.’ ” As for the blame Patten shares this time, Athena said, “It all happened on his watch.”

The MacQuarrie Report, the McAlpine version of the Pollard Review, headed by Ken MacQuarrie, BBC Scotland director, judged the hastily put-together piece a “serious failure of BBC journalism.” The B.I.J. producer who should have seen to the fact-checking on the story was moonlighting as a stand-up comic. Lord McAlpine told me, “They bought a package that would have finished me off in every respect and within a week exposed it without checking any facts. It’s not just sloppy journalism, it’s malice.”

There is nothing in the U.S. comparable to the position that “Auntie Beeb,” as the BBC is affectionately known in Great Britain, occupies in British life. The BBC is the last vestige of that proud declaration “The sun never sets on the British Empire.” Every household in Britain with a color TV set is mandated to pay the station an annual licensing fee of $230, which guarantees the institution, employer to more than 20,000 worldwide, a huge funding base that other, independent media entities in the United Kingdom do not enjoy. It is estimated that each week the average Briton devotes 19 hours to the BBC’s offerings on television, radio, and online. Its innovative Web-based iPlayer lets anyone catch up on the last week of BBC programming with a couple of clicks. I recently toured the grand new $1.6 billion BBC headquarters, in central London, which houses 6,000 employees, and where the BBC broadcasts via three 24-hour news TV channels and nine radio networks. I was stunned by its size. One enters through a piazza with audio in dozens of languages, embedded ground lights, and 750 squares with place names representing various parts of the earth where the BBC is heard; it has a thriving Web site and numerous other entities, from entertainment productions sold around the world to numerous items of merchandise. Through a sweeping glass wall on the entry level, one looks down on the main newsroom, where 300 people sit in front of their computers in long, open rows. On the fifth floor, I watched a TV news show being taped in Urdu, one of 26 languages in which the BBC broadcasts, and met journalists being trained to report the news to Myanmar.

The management structure of such a vast enterprise, where the head of television is called the director of Vision and bosses of the various radio and TV networks are called controllers, is not easily decoded. The director-general also holds the title of editor-in-chief. In this privileged world, the funds never dry up, and the “lifers” who rise through the ranks to become “barons” enjoy fat pensions and perks. The barons, however, have been increasingly criticized for their “silo mentality” and for using their strict church-state code of separation between news programs and everything else as an evasion of accountability. Just as the liberal BBC was thought to take an inordinate glee in the travails of its biggest competitor, Rupert Murdoch with his BSkyB, during the recent phone-hacking scandal, the mostly right-wing press as well as the liberal Guardian has seemed to pounce on every BBC misstep. “The BBC regards itself as a counterweight to Murdoch’s power,” a London financial executive told me. “The right wing and ITV hate the BBC, [because its] Internet site is killing everyone else and eating into their business.” According to BBC anchor Paxman, “There are vast vested interests at stake. The BBC is seen as a market disrupter. There is great appeal in trying to discredit it.”

One of the reasons given for why Mark Thompson’s successor, George Entwistle, a respected program producer, lasted only 54 days on the job is that he simply was not used to the unrelenting glare of Fleet Street. “He’d never been in the firing line before,” said Professor Stewart Purvis, a journalism blogger and former head of ITN. “When the British press goes for you, it’s an experience you never forget.” At the height of the McAlpine scandal, Entwistle gave a disastrous interview to John Humphrys, of BBC Radio4, in which he appeared to be out of touch and uninformed. “You should go, shouldn’t you?,” Humphrys demanded. That very day Entwistle was gone, but with a full year’s salary, which only further angered many. A leading London legal observer told me, “The general feeling is the BBC secretariat exists largely to look after itself.” To the BBC’s powerful creative director, Alan Yentob, however, such a failing was seen as a vindication: “There aren’t many organizations where you’re the boss and your executioner is the employee.”

After the recent scandals concerning expenses in Parliament and pedophilia in the Church of England, not to mention the failures of the press and the police in the phone-hacking miasma and the Savile travesty, it can appear at times that the center of British society is not holding. Last November, when judge Lord Leveson published his 2,000-page inquiry on the phone-hacking scandal, he sent chills through Fleet Street by strongly suggesting that the press in Britain should be regulated by law and held accountable to a stricter set of standards, thereby putting David Cameron in an uncomfortable position. The betting today is that there will not be formal legislation but, rather, beefed-up controls set by the press itself. Leveson devoted only one of the 2,000 pages specifically to the Internet, but the real game changer for everyone could well be what the BBC set in motion by violating its own code of conduct in not contacting McAlpine and thereby allowing his mis-identification via jigsaw on Twitter. “We are all going to have to be very careful now about what we all publish and air,” says Vanity Fair’s London libel attorney, David Hooper. This comes at a time when a number of British newspapers are hanging by a thread, when any day could bring the announcement of a major paper shutting down or being forced to continue online only.

‘The ravens have not left the Tower of London. Big Ben is still ringing,” Mark Thompson said, cautioning me to take the “post-apocalyptic landscape” with a grain of salt.

Of all those waiting to exhale in the wake of the Pollard Review, former BBC director-general Thompson, safely ensconced as the C.E.O. of The New York Times since November, has to be one of the most pleased. He has steadfastly maintained that he knew nothing of the row over Savile and hardly anything about the man himself. “I never worked with Jimmy Savile. I never worked in his department, or worked where he worked, or ever met him. I think he finished regular appearances in the early 90s, before I took over,” Thompson told me. “My clearest recollection of him is sitting at home watching him in my childhood and early teen years.” During Thompson’s tenure at the BBC, from 2004 until 2012, he said, “he appeared as a figure of the past. I think I’d heard he published a biography where he bragged about sexual conquests.”

Thompson said he was never briefed or notified about Savile. He denied to Pollard that he was aware of any of the seven print stories, at least several of which would have appeared in the daily BBC press clippings packet sent to top executives. He also told me that he had had no idea about the Freedom of Information request sent to his office by Miles Goslett, and that he had only verbally O.K.’d—without reading it—the very strongly worded letter threatening libel written by independent lawyers to The Sunday Times Magazine.

When first questioned by New York Times reporters, Thompson repeated that he had “never heard any allegations” about Savile while he was at the BBC, and that he did not know what the killed exposé was about. According to the Mail Online, “He later admitted to a British newspaper that after a conversation at a party he ‘formed the impression it (the Newsnight investigation) was about sex abuse.’ ” The reason for the admission was that Goslett had discovered that Caroline Hawley, a BBC reporter whom he did not name, had approached Thompson at a pre-Christmas party in 2011 and said he must be worried about Savile. Thompson subsequently asked Helen Boaden, director of news, about it. Since then Thompson has sought to clarify his position.

In a January 2013 letter to a member of Parliament sent from New York, for example, Thompson said he did remember a “chance conversation” at a cocktail party in December 2011, but neither Hawley nor the leadership of BBC News (Helen Boaden), with whom he subsequently raised it, “told me what the investigation had been about,” though he did know the story was abandoned on editorial grounds. He said that when he indicated to the Times “that I might have formed the impression at the time of my conversations with Caroline and Helen that the investigation related to allegations of sexual abuse, this was speculation on my part in October 2012 about an impression I might or might not have formed after a pair of brief conversations nearly a year earlier.”

Today it does not really seem to matter whether anyone can even parse that statement. Thompson has traded his role of heading his country’s most prestigious media empire for that of overseeing a much smaller, operation at this country’s most prestigious newspaper. Asked what he made of a BBC insider’s claim that Thompson has “failed up” and is a “floater, not a sinker,” Thompson remarked that during his tenure, “the BBC went on to have a really outstanding decade,” and that after taking an earlier job at Channel 4, he grew it “back to profitability. No one got fired or stabbed.” What about bitten, per a 1988 incident in which he bit a Nine O’Clock News colleague on the arm? “That was a very, very long time ago—it was a joke that went only slightly wrong.”

At present, he is far from the BBC turmoil that began in his tenure, and Pollard has declared his support: “I have no reason to doubt what Mr. Thompson told us.”

The Pollard Review cost British taxpayers more than $3 million and examined more than 10,000 documents. Rushed out in nine weeks just before Christmas, it concluded that the BBC was guilty of serious failings in oversight and management control, and that dropping the Savile piece “led to one of the worst management crises in the BBC’s history.” Moreover, “the BBC’s management system proved completely incapable of dealing with it.” However, flawed as the decision was, the Pollard Review concluded that it was made in good faith, that there was no attempt to suppress the story.

For those who have covered Newsnight and Savile from the beginning, plus some of those directly involved, however, the report was deeply unsatisfying. “I think it’s completely useless,” Miles Goslett told me. “It doesn’t satisfy my curiosity. I still don’t know why it wasn’t shown on TV.” The reason, it seems from the report, had to do with the persistently vague memories of those making some of the crucial decisions and the fact they all had their own lawyers, paid by the BBC to defend against anything critical said about them. The report makes clear that there was “personal animosity” between the Newsnight editor, Peter Rippon, and the producer Meirion Jones, who was widely considered a leaker (which Jones strongly denies) and was not trusted—to the extent that one press officer sent an e-mail saying he would “drip poison about Meirion’s suspected role.” However, Pollard apparently never attempted to ask why Rippon, or anyone else, didn’t just go to Jones’s partner on the piece, reporter Liz MacKean, who was not suspected of leaking to the press, to get her opinion of the sources. Amazingly, Rippon killed the piece without ever having seen any on-camera interviews of the principals involved. He did not know or remember that more than one woman had been interviewed. And when Entwistle was confronted with a forensic examination proving that an e-mail he said he could not remember reading had indeed been opened, twice, he still could not remember. Throughout the 185 pages, it’s hard to find management taking responsibility for anything, particularly when everyone has such strict respect for non-interference in someone else’s line of authority. Very few at fault have gotten axed, and most people have moved sideways; even Stephen Mitchell, who will retire on time with his pension, and Peter Rippon who left Newsnight but remains at the BBC. Helen Boaden, who had been re-installed as head of news, was appointed on February 14th to the position of director of BBC Radio—another plum job. “What everyone’s done is get away with it,” a BBC reporter told me, echoing widespread skepticism in the building.

BBC executives seem very pleased with the report. “There is no question of conspiracy or collusion,” said Alan Yentob. “It’s not a cover-up, it’s a cock-up.” He characterized the main features of the controversy as “slight mistrust” between Rippon and Jones and “bad communication.” He also pointed out that trust in Auntie Beeb, which dipped after the Savile charges were aired, is now climbing back up. Lord Patten, of the BBC Trust, was not quite so sanguine: “It portrays an organization where chaos and confusion could have been avoided through better leadership, organization, and communication.” He is demanding that the next director-general, Royal Opera House chief executive Tony Hall, produce an overhaul in three months.

Next up is the detailed inquiry into the “culture and practices” of the BBC, led by former High Court judge Dame Janet Smith, out sometime in the next year or so. And victims are now beginning to sue the BBC and Jimmy Savile’s estate for what they have endured—there are no “punitive damages” for sexual abuse in Britain, however; damages for libel are larger. The police inquiries continue, and at last count 39 past and current BBC presenters and employees have been accused of sexual misconduct. Also snared by the Savile investigation was English pop star Gary Glitter, who was previously convicted on child pornography charges and was reported to have had sex with an under-age girl in front of Savile and others in Savile’s dressing room. A number of aging 60s and 70s TV and radio entertainers and other, behind-the-scenes figures have also been arrested. The police report released in January details approximately 600 complaints of sexual misconduct—about 450 concerning Savile—from all over England. The report’s lead investigator said Savile “groomed a nation.” The BBC is now officially “appalled” by his crimes.

Original Publication: vf.com, February 2013.