“This Is All So Familiar”: Talking to Maureen Orth About Michael Jackson, Woody Allen, and Celebrity in 2019

The Vanity Fair journalist covered Jackson’s and Allen’s stories in the ’90s—and has watched much of her reporting find new relevance in recent years

Kate Knibbs Mar 6, 2019, 8:23am EST

The Vanity Fair journalist covered Jackson’s and Allen’s stories in the ’90s—and has watched much of her reporting find new relevance in recent years

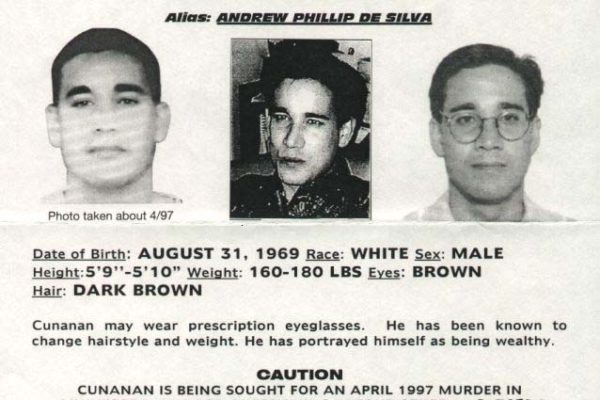

Veteran magazine journalist Maureen Orth covered true crime, politics, and celebrity culture for decades, frequently writing cover stories for Vanity Fair. Herwork ranges from lengthy profiles of Vladimir Putin and Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams to in-depth trial reporting on high-profile crimes like the murders of Laci Peterson and Gianni Versace to heavily researched explorations of the celebrity of Madonna and Tina Turner. Her most recent piece for Vanity Fair, however, is a succinct, list-style blog post.

The 76-year-old National Magazine Award winner wrote a listicle for a good reason. A new HBO documentary, Leaving Neverland, details the stories of two men who say Michael Jackson molested them as children, and the film has prompted a reassessment of the pop star’s legacy. (The Jackson estate is suing HBO over the movie’s release.) Orth reported on allegations against Jackson from 1994 to 2005, interviewing children and the families of children who said that the pop star had sexually abused them, documenting two cases and withstanding fierce criticism from Jackson fans. Her work on Jackson documented deeply horrifying witness testimony, but the King of Pop maintained a robust, devoted fan base until his death. Now, Leaving Neverland has spurred a re-evaluation of Jackson’s legacy, as well as the media coverage and public reaction to the many allegations of abuse against the singer.

The Ringer spoke to Orth about the renewed attention to a story she documented so many years ago, as well as the ways that #MeToo and celebrity culture have shaped the way people hear stories about abuses of power.

You reported in-depth on the Michael Jackson trial for Vanity Fair as it happened decades ago. You also reported on Dylan Farrow and Mia Farrow’s accounts of Woody Allen abusing Dylan as a child decades ago. Why do you think the cultural reckoning for these men took so long?

We are a society that absolutely worships fame and celebrity. Michael Jackson and Woody Allen, particularly, were two men who were considered to be incredible geniuses. The establishment media at the time that these original accusations occurred were in utter thrall.

The establishment press did not give the kind of scrutiny to these charges that they would have given to similar kinds of charges had they come out of Washington about politicians. At the time, this was considered the purview of tabloid fodder. I think the general media landscape had a lot to do with it. Before Harvey Weinstein, ordinary people didn’t have the PR power behind them, or have at their disposal all the venues that Michael Jackson and Woody Allen had. When I wrote about Woody Allen, he had gotten the cover of Time, Newsweek, The New York Times Sunday magazine, People—everybody! It was only his point of view. By the time I got around to doing the piece on Vanity Fair that was Mia’s story—my first piece about Woody Allen—so much of the other stuff had gone on that I had thought, “I’m only reading one side.” I had no preconceived notions whatsoever. I just thought there had to be another side to this, and that’s when I started doing my reporting on Woody. So Woody was first, and then Michael Jackson happened right afterwards.

Both men, because they were considered geniuses, didn’t have to answer for their time. People were in awe, they worshipped them. So they could do whatever they wanted with their time, and nobody questioned them. Because they were such hot commodities, they escaped scrutiny.

Can we talk about the reactions to your original reporting on Jackson and Allen?

In the Leaving Neverland documentary, there’s a brief exchange between Katie Couric and Johnnie Cochran, who was O.J. Simpson’s lawyer, about Vanity Fair saying something—it was about my article. Johnnie Cochran didn’t deny what was in the article, he just said, “I don’t believe anything I read in Vanity Fair, do you?” There’s a non-denial denial.

It’s very important to understand that, given the huge amount of firepower these people had in terms of going after Vanity Fair and me legally, we were never, ever sued. We were extremely careful in fact-checking. We went through a very rigorous legal fact-checking process. I remember, for the legal fact-checking process on the Woody Allen piece, I was in a room with the fact-checkers for eight hours. They weren’t going to allow the piece to be published until I had a written letter from Mia Farrow saying if we did get sued, she would be a witness to say what I had said was the truth from her point of view. We go to very strong lengths to be accurate, and we were never sued.

What has it been like to see the #MeToo movement unfold?

I hear these stories, and I see these people come forth, and I think to myself, “My god, this is all so familiar, I knew all this decades ago.” I also did a big story on a pedophile priest, Paul Shanley, who was this big Boston street priest, and I did another story on Jimmy Saville, who was a famous BBC radio and TV guy who was also accused of abusing 400 minors, and the patterns are all, so much, the same. It’s all so much the same. It doesn’t vary that much.

There’s other ironic things, like Bill Cosby’s lawyer at his second trial was the same lawyer that Michael Jackson had, so obviously Bill Cosby thought he had a shot at being exonerated, since Tom Mesereau had gotten Jackson off. And then Harvey Weinstein’s lawyer when he was first accused was Woody Allen’s lawyer. I’d just see all these interesting little threads that hang together.

When I read your book The Importance of Being Famous, I was struck by how prescient a lot of your commentary on celebrity culture is. There’s a sentence: “Entertainment always trumps politics where coverage is concerned, although in the Age of Celebrity, superstars and presidents are increasingly part of the same entity: the world of the famous.” I’m wondering if you think this Age of Celebrity will ever end.

No, because I think you can draw a straight line between the Kardashians and Donald Trump. He borrowed a lot from how they behaved, and now it’s become inculcated into our culture. Look at the coverage of Luke Perry’s death—it’s leading the news. I don’t think this is changing anytime soon. There are so many media mouths to feed, and that’s not going away. Unless they all go bankrupt.

It’s very belated, but do you think that the fact that people are starting to take these stories of abuse more seriously now is a sign that the media will have an easier time holding powerful men accountable in the future?

That’s always the hope, isn’t it?

You also have to hold the media accountable, to be more thorough in how they do their jobs. The public might be there, but the media also has to be there and not be sloppy, to do the legwork and the reporting. For example, one of my stories about Michael Jackson was about this famous—or infamous—interview he had with ABC and Diane Sawyer. ABC made unprecedented accommodations and concluded a showbiz/entertainment contract with him at the very same time that appeared to be the price of admission for his interview. And then Diane Sawyer made all these mistakes. You can go read it—“The Jackson Jive.” Then somebody wrote a big story yesterday and didn’t seem to be aware of the Diane Sawyer “Jackson Jive” story. You need to go beyond the first story. You gotta do the work.

It doesn’t seem like the media ecosystem is always set up for thoroughness.

That’s why “10 Undeniable Facts” is easier to get people’s attention.

Did Vanity Fair approach you to do that as a one-off? Are you working on any other stories for them right now?

Actually, that was my idea, to do the “10 Undeniable Facts,” and to call attention to the fact that so much of this has been reported before.

But, yes, I’m working on something. I have a foundation in Colombia that started from my Peace Corps experience. I work with 21 schools with technology, English, and leadership. Last week, I was in Medellín because the city and mayor of Medellín blew up Pablo Escobar’s old building, because they’re sick and tired of the narrative always being a Narcos narrative, which is not from the point of view of the victims. It’s a good illustration of where we’re at today. Medellín has made an incredible turnaround; it was voted the most dynamic city in the world in 2016, beating out New York and Tel Aviv, and what do most people think about? Narcos. That’s how the media focuses. So they’ve got a new campaign about Medellín embracing its history, and since I have such a long personal history there, I’m writing about that next.

There’s an ongoing discussion about how people should consume—or whether they should consume at all—art made by abusive people. I’m wondering what your thoughts are on that.

I struggle with that. I was a huge fan of Michael Jackson’s music. I stopped seeing Woody Allen movies. Mia Farrow was in 13 of his movies, and she never got paid more than $200,000 a movie—he was really one of the most keeping-it-for-himself directors there are, and on so many levels I thought it was unfair. I have a hard time with that one.

Am I never going to be able to hear “Billie Jean” again? There was a woman who called me at the time and claimed she was the real Billie Jean, and she thought her son was Michael’s son, and that was the basis of the song? Reality trumps fantasy when you’re doing this kind of reporting, but I haven’t got a good answer for that one. Will I turn off Michael Jackson the next time I hear one of his great songs? I don’t think I’m there yet. It’s easier to not go to a movie than to shut out all of the great motown stuff [Jackson] was associated with.

I don’t have a good answer for it either.

But I do have to say that there was no way that Michael Jackson would have gotten away with all this for so many years without enablers. Very sophisticated, very smart enablers who just looked the other way because of who he was—a celebrity.

This interview has been edited and condensed.