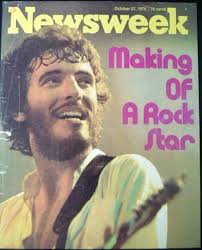

Newsweek – November 27, 1975

The movie marquee in Red Bank, N.J., simply said “HOMECOMING” because everyone knew who was home. Out in the audience was Cousin Frankie, who taught him his first guitar chords. So were the guys from Freehold High who played in his early rock ‘n’ roll bands. They did not have to be hyped on Bruce Springsteen. This was the scruffy kid they had seen for years in the bars and byways of coastal Jersey. But Bruce was suddenly big time. The rock critics, the media, the music-industry heavies all said so. And in Red Bank, Bruce showed them just how far he had come. With Elvis shimmies and Elton leaps, Springsteen re-created his own electric brand of ’50s rock ‘n’ roll magic. He clowned with saxophonist Clarence Clemons, hustled and bumped his way around the stage and gave a high-voltage performance that lasted more than two hours. When he leaned into the microphone, ripped off his black leather jacket and blasted, “Tramps like us, baby, we were born to run,” the Jersey teeny-boppers went wild. After four foot-stomping encores they were ready to crown Bruce Springsteen the great white hope of rock ‘n’ roll.

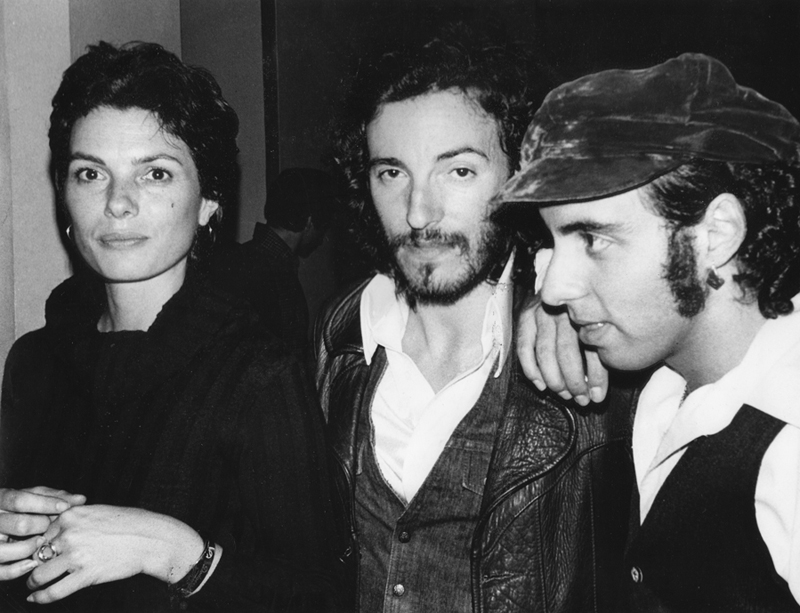

The official investiture took place last week in Los Angeles at Springsteen’s carefully staged West Coast debut at the Roxy Night Club on Sunset Strip. At the kind of opening-night event that defines hip status for at least six months, new Hollywood and rock royalty embraced Bruce Springsteen as one of their own. In a rare ovation that lasted a full four minutes, Jack Nicholson, Ryan and daughter Tatum O’Neal, Wolfman Jack and Neil Diamond seconded Cousin Frankie and the boys from Freehold High in Red Bank. Bruce Springsteen was a superstar.

Bruce who? He is still not exactly a household name across America. In San Mateo, Calif, last week, his 13-year-old sister Pam said, “Only one girl at school has his record.” The bus driver’s son – who bears a striking resemblance to Dylan, sports black leather jackets like Brando in “The Wild One” and wears a gold hoop earring – was known to only a small coterie of East Coast devotees a year ago. But since the release last August of his highly professional third album, “Born to Run,” which rocketed to a million-dollar gold album in six weeks, 26-year-old Bruce Springsteen has exploded into a genuine pop-music phenomenon. He has already been compared to all the great performers – Elvis, Dylan and Mick Jagger. And rock critic Robert Hilburn of The Los Angeles Times called him “the purest glimpse of the passion and power of rock ‘n’ roll in nearly a decade.” Spingsteen’s own insistence on performing in small halls and clubs has created a kind of cult hysteria and his emergence as one of the most exciting live acts in rock today has only added to the mystique. Sprinsteen buttons, T-shirts, decals, key chains and three different kinds of wall posters are currently the hot rock paraphernalia. In fact, Bruce Springsteen has been so heavily praised in the press and so tirelessly promoted by his record company, Columbia, that the publicity about his publicity is now a dominant issue in his career. And some people are asking whether Bruce Springsteen will be the biggest superstar or the biggest hype of the ’70s.

In a $2 billion industry that thrives on smash hits, the artist who grabs the public’s emotions the way Elvis or the Beatles once did is the fantasy of rock critics and record industry pros alike. Springsteen’s punk image, his husky, wailing voice, his hard-driving blues-based music and his passionate, convoluted lyrics of city lowlife, fast cars and greaser rebellion recall the dreams of the great rock ‘n’ roll rage of the 1950s:

Well now I’m no hero

That’s understood

All the redemption I can offer, girl

Is beneath this dirty hood

But he also injects the images with a new sophistication:

The highways jammed with broken heroes

On a last-chance power drive

Everybody’s out on a run tonight

But there’s no place left to hide

Some critics, however, find Springsteen’s music one-dimensional, recycled teen dreams. “Springsteen’s lyrics are an effusive jumble,” music critic Henry Edwards wrote in The New York Times, “his melodies either second-hand or undistinguished and his performance tedious. Given such flaws there has to be another important ingredient to the success of Bruce Springsteen: namely, vigorous promotion.” Even some of his champions like disk jockey Denny Sanders of WMMS in Cleveland agree on that point. “Columbia is going overboard on Springsteen,” he says. “He is the only unique artist to come out of the ’70s, but because the rock ‘n’ roll well is really dry, they are going crazy for Springsteen.”

As the real world has caught up with the record world, the penny-pinched economy has begun to erode the record industry. Album sales are down (Warner Brothers, for one, is off by nearly 20 percent), the albums going to the top of the charts are getting there on fewer sales while advertising budgets are being drastically slashed. “Unless an act has a great potential for sales,” says one record-company executive, “the companies won’t spend the big dollars.”

Too often, the companies have gotten burned when they spent their money on the sizzle and forgot the steak. Bell Records dished out more than $100,000 last year in parties to promote an act nobody ever heard of – Gary Glitter – and people are still asking who he is. Atlantic bankrolled the rock group Barnaby Bye for an estimated $200,000 but failed to turn up an album sales. MGM decided to promote a singer-songwriter named Judi Pulver. They sent her to a Beverly Hills diet doctor, created a Charles Schulz “Peanuts” ad campaign, rented a Boeing 720 to fly journalists to her openings in San Francisco and even got astronaut Edgar Mitchell to go along for the ride. When the evening was over, the inevitable truth set in. Judi Pulver just couldn’t carry the hype. MGM’s $100,000 experiment bombed.

Everyone in the industry is aware of the pitfalls of The Hype and insiders think that the current Springsteen mania might inflict damage on his career. “All the attention Bruce is getting now might hurt him later on,” says Hilburn. “What I’m afraid of is what while Springsteen has all the potential everyone says he has, it’s still chiefly potential. I just hope he’s strong enough to stand up under the pressure.” Warner Brothers Records president Joe Smith appreciates the “tumult” Bruce is creating for the industry but is dubious about the extent of his ultimate influence on the development of music. “He’s a hot new artist now,” says Smith, “but he’s not the new mesiah and I question whether he will establish an international mania. He’s got a very long way to go before he does what Elton has done, or Rod Stewart or The Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin.”

Bruce himself is concerned about the effect the publicity campaign will have on his creative equilibrium. “What phenomenon? What phenomenon?” Springsteen asked in exasperation last week while driving up from Jersey to New York. “We’re driving around, and we ain’t no phenomenon. The hype just gets in the way. People have gone nuts. It’s weird. All the stuff you dream about is there, but it gets diluted by all the other stuff that jumped on you by surprise.”

Springsteen is experiencing superstar culture shock. He has never strayed far from his best friends like Miami Steve Van Zandt and Gary Tallent, who are in his E Street Band. He has spent hours hanging out on the boardwalk at Asbury Park, N.J., and listening to the barkers tell their tales. For gigs, he used to hitchhike to New York to play his guitar in Greenwich Village. In both places, he found the cast of characters who people his lyrics – Spanish Johhny, the Magic Rat, Little Angel, Puerto Rican Jane. They inspired him but they didn’t corrupt him. Springsteen rarely drinks, does not smoke, doesn’t touch dope and never swears in front of women.

“I’m a person – people tend to forget that kind of thing,” he says. “I got a rock ‘n’ roll band I think is one of the best ones. I write about things I believe that are still fun for me. I love drivin’ around in my car when I’m 26 and I’ll still love drivin’ around in my car when I’m 36. Those aren’t irrelevant feelings for me.” The feelings usually find their way to vinyl. “The record is my life,” says Springsteen. “The band is my life. Rock ‘n’ roll has been everything to me. The first day I can remember lookin’ in the mirror and standin’ what I was seen was the day I had a guitar in my hand.”

Throughout his unconventional career, Springsteen has found people who felt he was born to star. From the moment he and his abrasive new manager, Mike Appel, walked into Columbia Records in 1972 to audition for the legendary John Hammond – discoverer of Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan – Springsteen was the subject of high-pressure salesmanship. “I went into a state of shock as soon as I walked in,” says Springsteen. “Before I ever played a note Mike starts screamin’ and yellin’ bout me. I’m shrivelin’ up and thinkin’, ‘Please, Mike, give me a break. Let me play a damn song.’ So, dig this, before I ever played a note the hype began.”

“The kid absolutely knocked me out,” Hammond recalls. “I only hear somebody really good once every ten years, and not only was Bruce the best, he was a lot better than Dylan when I first heard him .” Within a week, Springsteen was signed to Columbia and although he and Appel had little previous recording experience, they insisted on producing their own album – the uneven “Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.” released in January 1973. At the time Bruce had no band; he sang alone with an acoustic guitar. And because of the originality of his lyrics – and perhaps the familiarity of their cadence – he was compared to Dylan.

Oh, some hazard from Harvard

Was skunked on beer playin’ Backyard bombadier

Yes and Scotland Yard was trying Hard,

they sent some dude with a Callin’ card

He said, “Do what you like but don’t do it here.”

The comparison was so tantalizingly close that Columbia promoted the first album with ads announcing they had the new Bob Dylan. The cover letter on the records Columbia sent to the DJ’s flatly stated the same thing. But the hard sell backfired. “The Dylan hype from Columbia was a turnoff,” said Dave Herman, the early-morning DJ for WNEW-FM, the trend-setting pop station in New York. “I didn’t even bother to listen to it. I didn’t want Columbia to think they got me.”

Without radio airplay – the single most important ingredient in any hit – a record dies. Though the Springsteen campaign was a special project of then Columbia president Clive Davis, who personally read Springsteen’s lyrics on a promotional film, and even though Bruce got good notices from important rock publications like Crawdaddy, only a handful of the 100 or so major FM stations across the country played him. The record sold less than 50,000 copies.” “He was just another media hype that failed,” said Herman. “He was already a dead artist who bombed out on his first album.”

Springsteen’s personal appearance at the Columbia Records convention in the summer of 1973 was his biggest bomb. “It was during a period when he physically looked like Dylan,” says Hammond. “He came on with a chip on his shoulder and played too long. People came to me and said, ‘He really can’t be that bad, can he, John?”

That fall, Springsteen’s second album, “The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle,” was released. Again it got some terrific reviews – Rolling Stone later named it one of the best albums of 1974 – but it sold even less than his first LP. This time, accompanying a stack of favorable reviews, the DJ’s got a letter from Springsteen’s manager Appel saying “What the hell does it take to get airplay?” Meanwhile, Springsteen had a disastrous experience playing as the opening act for the supergroup Chicago on tour, and he refused to do what most new rock acts must do to get exposure – play short, 45-minute sets in huge halls before the main act goes on.

Columbia began to ignore Springsteen because he couldn’t make a best-selling album or hit-single. But Springsteen was getting better in his live performances and was starting to build followings in towns like Austin and Philadelphia, Phoenix and Cleveland. “The key to Bruce’s success was to get people to see him,” says Ron Oberman, a Columbia staffer who pushed hard for Springsteen’s first album within the company. After a concert in Cleveland, says local DJ Sanders, “Springsteen was a smash and requests zoomed up. We had played him before but now the requests stayed on.”

In April 1974, Jon Landau, the highly respected record editor of Rolling Stone, caught Bruce’s act in Boston, went home and wrote an emotional piece for the Real Paper stating. “I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” Landau’s review was the turning point in Springsteen’s faltering career – for the artist as well as the company. “At the time,” says Springsteen, “Landau’s quote helped reaffirm a belief in myself. The band and I were making $50 a week. It helped me go on. I realized I was gettin’ through to somebody.” Columbia cannily used the blurb in marketing Springsteen’s second album and other critics began to take notice. It was the first time a record label used the prestige of a rock critic to push an artist so hard.

“His first two albums’ not selling was the best possible thing for Bruce,” says the 28- year-old Landau. “It gave him time to develop a strong identity without anyone pushing him prematurely. For twelve years he has had time to learn how to play every kind of rock ‘n’ roll. He has far more depth than most artists because he really has roots in a place – coastal Jersey, where no record company scouts ever visit.”

One month after the Landau review, Springsteen, alone with Mike Appel in a sparsely equipped studio in upstate New York, began to record his third album – his last chance to make it. It took three months to record the title song, “Born to Run,” and Columbia immediately sent it out to some key people to review for singles potential. The word came back: It’s not Top 40, forget it, it’s too long. Then the ever-assertive Appel release a rough mix of the song to a handful of stations that had played Springsteen.

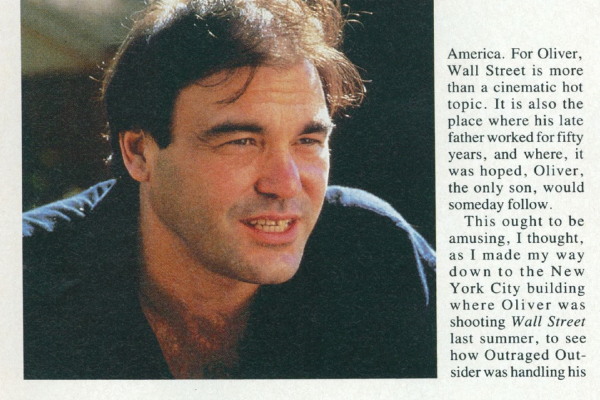

The response was overwhelmingly positive. The stations wanted the record. But the potential superstar was in the studio for the next six months unable to finish his masterpiece. “He told me he was having trouble getting the sound he heard in his head on record,” says Landau. In April 1975, a year after his review, Landau became an adviser on the album and quit his job at Rolling Stone to become co-producer. He moved them into a better studio and helped shape the album into a heavily produced wall of pulsating sound.

Last June, a group of Columbia executives heard a rough cut of the album and decided to launch an unprecedented campaign. Building on the Landau quote and $40,000 worth of radio spots on FM stations in twelve major markets, they promoted the first two dud albums, mentioning a third was on the way. It worked. Sales for the first two LP’s climbed back on the charts, more than doubling their original sales.

Columbia knew it had a winner, the question was how to showcase the act. Appel, without consulting Springsteen, thought big. He asked a booking agent to get 20,000-seat Madison Square Garden for an artist who had never sold more than 150,000 records. He finally settled on the 400-seat Bottom Line club in Greenwich Village for the week before the release of the third album last August. The tickets sold out in three and a half days, with Columbia picking up 980 of the 4,000 tickets for the media “tastemakers.” “Columbia put it on the line,” said DJ Richard Neer of WNEW-FM. “They said, ‘Go see him. If you don’t like him, don’t play him – don’t write about him’.” With the tickets so limited in number, the ensuing hysteria created more press coverage and critical acclaim for Springsteen – who delivered topnotch shows – than any recent event of its kind. “It was a very intelligent use of an event,” says Stan Shadowsky, co-owner of the Bottom Line. “Columbia got all the right people down there.” DJ Dave Herman, who refused to even play Sprinsteen’s first album because of the hype, was completely won over. The next day he apologized on the air. “I saw Springsteen for the first time last night,” he told his audience. “It’s the most exciting rock ‘n’ roll show I’ve ever seen.”

Orders for the new album, which had been given an initial press ordering of 175,000, came in at 350,000. The LP has sold 600,000 so far, and Columbia has spent $200,000 promoting it. By the end of the year they will spend an additional $50,000 for TV spots on the album. “These are very large expenditures for a record company; we depend on airplay, which cannot be bought,” says Bruce Lundvall, Columbia Records’ vice president. “What the public does not understand is that when you spend $100,000 on an album for a major artist, your investment is not so much on media as on the number of people you have out there pushing the artist for airplay.” Now, for the first time, a Springsteen single, “Born to Run,” has broken though many major AM stations, where the mass audience listens.

The stakes are enormous, since a hot album can earn up to several million dollars for the record company in a matter of a few weeks. Today Bruce Springsteen is still a promising rookie. Nobody knows whether he can sell like Elton John or even lesser publicized groups like Earth, Wind & Fire — a group that will ship more than 750,000 initial orders with the release of its new L.P. Because of his enormous build-up, Springsteen now has the awesome task of fulfilling everyone’s fantasy of what a new rock hero should be. And most of the country – which isn’t even aware of Springsteen yet – may or may not agree that he is born to succeed. “Bruce is undergoing a backlash right now,” says Irwin B. Segelstein, President of Columbia Records, “but even his critics are treating him importantly.”

Springsteen himself has not yet seen any big bucks. He keeps 22 people on his payroll. He maintains sophisticated sound and lighting equipment for his shows and has video crew following him everywhere. He only plays small halls where he can barely cover his expenses, but that hasn’t put a crimp in his style. He has just moved into his first home, a sparsely furnished cottage overlooking the ocean – about a 10-minute drive from the Asbury Park boardwalk. His girlfriend, 20-year-old Karen Darbin, a Springsteen fan from Texas, lives across the Hudson River in Manhattan. In Bruce’s garage stands his prized possession – a ’57 yellow Chevy convertible customized with orange flames, the same color as his first guitar.

On the eve of his West Coast debut last week, Springsteen seemed to be down. “People keep telling me I ought to be enjoying all this but it’s sort of depressing to me.” He riffled through his beloved ’50s records – Elvis and Dion – from stacks of albums on the floor, which also included Gregorian chants, David Bowie and Marvin Gaye. “Now this,” Bruce announces in a faintly Jimmy Durante delivery, “is the sound of universes colliding.” The room fills with Phil Spector’s classic production of the Ronettes’ “Baby I Love You.” Springsteen swoons. “Come on, do the greaser two-step,” he says, beginning to dance.

Although Springsteen is a German name, Bruce is mostly Italian, and he inherited his storytelling ability from his Neapolitan grandfather Zirili. “In the third grade a nun stuffed me into a garbage can she kept under her desk because she told me that’s where I belong,” he relates. “I also had the distinction of being the only altar boy knocked down by a priest on the steps of the altar during Mass. The old priest got mad. My Mom wanted me to learn how to serve Mass but I didn’t know what I was doin’ so I was tryin’ to fake it.”

He finally saved $18 to buy his first guitar – “one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen in my life” – and at age 14, Springsteen joined his first band. He was originally a Rolling Stones fanatic but gradually worked back to early rock. “We used to play the Elks Club, the Rollerdrome and the local insane asylum,” he says. “We were always terrified at the asylum. One time this guy in a suit got up and introduced us for twenty minutes sayin’ we were greater than the Beatles. Then the doctors came up and took him away.”

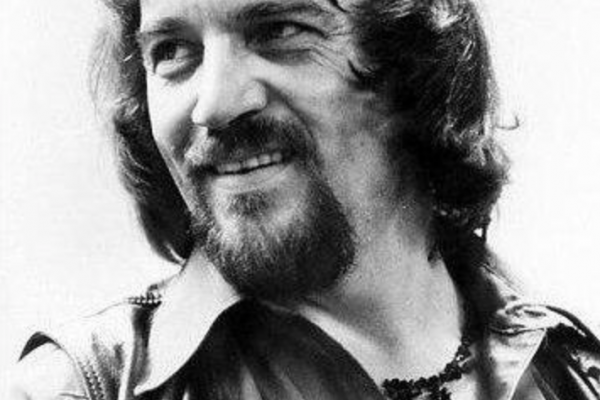

Springsteen’s parents moved to California when he was 16, but he stayed behind scuffling in local bands. A year later he drove across country – someone else had to shift because Bruce did not know how to drive – to play a New Year’s Eve gig at the Esalen Institute. “I’ve never been outta Jersey in my life and suddenly I get to Esalen and see all these people walkin’ around in sheets,” he says. “I see someone playing bongos in the woods and it turns out to be this guy who grew up around the corner from me.” “Everybody expected Bruce to come back from California a star,” says his old friend “Southside Johnny” Lyon who used to play with Bruce at the Stone Pony bar in Asbury Park. But according to Bruce, “nobody wanted to listen to a guy with a guitar.”

They do today. Onstage Springsteen projects the same kind of high school macho and innocence that many young male fans, for whom glitter is dull, strongly identify with. Women think he’s sexy and it’s likely he’ll end up with with a movie contract. “He’s able to say what we can’t about growing up,” said John Bordonaro, 23, a telephone dispatcher from the Bronx who traveled to Red Bank to see Bruce in concert. “He’s talking about hanging around in cars in front of the Exxon sign. He’s talking about getting your hands on your first convertible. He’s telling us it’s our last chance to pull something off, and he’s doing it for us.” “The peace and love movement is gone,” chimed in his friend, Chris Williams. “We have to make a shot now or settle into the masses?”

The question is will Bruce Springsteen be able to reach the masses? “Let’s face it,” says Joe Smith of Warner Brothers Records. “He’s a kid with a beard in his 20s from New Jersey who happens to sing songs. He’s not going to jump around any more than Elton. His voice won’t be any sweeter than James Taylor’s and his lyrics won’t be any heavier than Dylan’s.”

Springsteen’s promoters would disagree, but they don’t think it matters. “The industry is at the bottom of the barrel,” declares Springsteen’s manager Mike Appel, 32, as he paces around the Manhattan office once occupied by Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman. “We’ve got people scratching around looking for new talent. There’s an amazing paucity of talent because there hasn’t been anyone isolated enough to create a distinctive point of view.” He whispers dramatically, “What I’m waiting for, what Bruce Springsteen is waiting for, and we’re all waiting for is something that makes you want to dance!” He shouts, “Something we haven’t had for seven or eight years! Today anything remotely bizarre is gobbled up as the next thing. What you’ve got to do is get the universal factors, to get people to move in the same three or four chords. “It’s the real thing! Look up America! Look up America!” Appel sat down.

Hypes are as American as Coca-Cola so perhaps – in one way or another – Bruce Springsteen is the Real Thing.

Written with JANET HUCK in New York and PETER S. OREENBERG in Los Angeles

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments