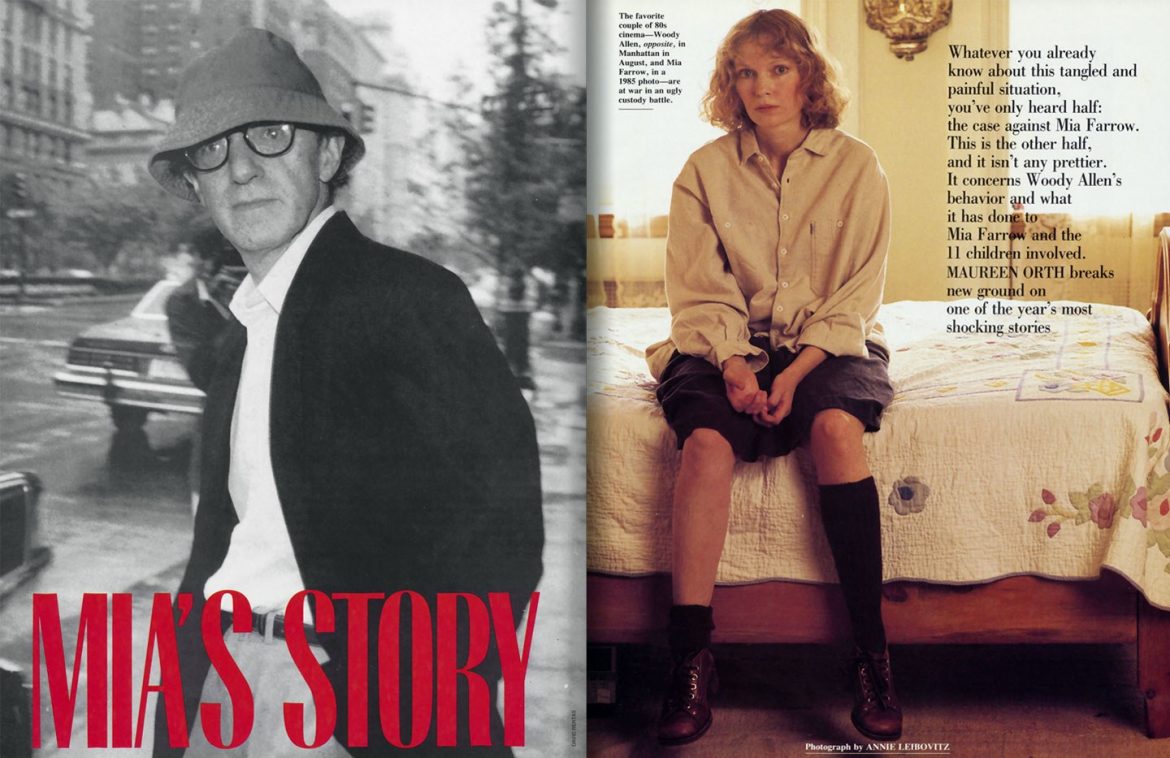

Vanity Fair – November, 1992

There was an unwritten rule in Mia Farrow’s house that Woody Allen was never supposed to be left alone with their seven-year-old adopted daughter, Dylan. Over the last two years, sources close to Farrow say, he has been discussing alleged “inappropriate” fatherly behavior toward Dylan in sessions with Dr. Susan Coates, a child psychologist. In more than two dozen interviews conducted for this article, most of them with individuals who are on intimate terms with the Mia Farrow household, Allen was described over and over as being completely obsessed with the bright little blonde girl. He could not seem to keep his hands off her. He would monopolize her totally, to the exclusion of her brothers and sisters, and spend hours whispering to her. She was fond of her daddy, but if she tried to go off and play, he would follow her from room to room, or he would sit and stare at her. During the school year, Allen would arrive early at Mia Farrow’s West Side Manhattan apartment, sit on Dylan’s bed and watch her wake up, and take her to school. At her birthday party last July, at Farrow’s country house in Bridgewater, Connecticut, he promised that he would keep away from the children’s table so that Dylan could enjoy her birthday party with her friends, but he seemed unable to do that. Allen, who was a fearful figure to many in the household, was so needy where Dylan was concerned that he hovered over her through the whole party, and when the cake arrived, he was right behind her, helping to blow out the candles.

Calling attention to someone’s birthday-party behavior may seem trivial at best. However, Dr. Coates, who just happened to be in Mia’s apartment to work with one of her other children, had only to witness a brief greeting between Woody and Dylan before she began a discussion with Mia that resulted in Woody’s agreeing to address the issue through counseling. At that point Coates didn’t know that, according to several sources, Woody, wearing just underwear, would take Dylan to bed with him and entwine his body around hers; or that he would have her suck his thumb; or that often when Dylan went over to his apartment he would head straight for the bedroom with her so that they could get into bed and play. He called Mia a “spoilsport” when she objected to what she referred to as “wooing.” Mia has told people that he said that her concerns were her own sickness, and that he was just being warm. For a long time, Mia backed down. Her love for Woody had always been mixed with fear. He could reduce her to a pulp when he gave vent to his temper, but she was also in awe of him, because he always presented himself as “a morally superior person.”

One summer day in Connecticut, when Dylan was four and Woody was applying suntan lotion to her nude body, he alarmed Mia’s mother, actress Maureen O’Sullivan, and sister Tisa Farrow when he began rubbing his finger in the crack between her buttocks. Mia grabbed the lotion out of his hand, and O’Sullivan asked, “How do you want to be remembered by your children?” “As a good father,” Woody answered. “Well, that’s interesting,” O’Sullivan replied. “It only lasted a few seconds, but it was definitely weird,” says Tisa Farrow.

Woody’s own mother was heard to remark on his fawning behavior with Dylan when Woody and Mia would take the children over for visits. “She’s the Wicked Witch of the West, Dylan,” Woody, who seemed to have intense negative feelings for his mother, once said to the little girl. “Twist her nose off.”

No such favoritism was shown toward four-and-a-half-year-old Satchel, Woody’s own son by Mia. Father and son seemed to have been allergic to each other from the start. Mia told friends that Woody appeared to be disturbed by her cesarean, from which she took a long time to recover; he was aghast at her nursing, particularly at a tube device that carried milk from a bottle down next to her nipple during the first week to give the baby formula when her own milk didn’t come in immediately, as well as at the fact that Satchel wasn’t fully weaned until he was two and a half. She said that Woody referred to the baby, who cried a lot, as “the little bastard,” and that once, when Satchel kicked Woody, Woody twisted Satchel’s leg until he screamed, and said, “Do that again and I’ll break your legs.” On another occasion, Satchel poked Dylan in the eye in Woody’s presence. Woody scooped up the little girl, cradled her in his arms, and railed obscenely at Satchel. “I just don’t buy it when a parent becomes so constantly angry at such a little boy,” says Casey Pascal, who witnessed the scene. Pascal, Mia’s friend since boarding-school days in England, also has a seven-year-old, plus twins Satchel’s age, and often visits Mia both in the country and in the city. “Woody clearly said he wanted a girl. Satchel was wrong from the beginning for him.”

Dylan, who has just begun second grade, tests in the upper-90th percentile. Contrary to recent reports in the press, she has, according to family members, never been in therapy for an inability to distinguish fantasy from reality. She has been in therapy for separation anxiety (she didn’t want to be left by her parents at nursery school) and for her shyness. Indeed, people wondered how she could cope with so much doting attention from her father—behavior that many people frankly didn’t know what to make of. “When she just wanted to giggle and run away and play, he’d be right behind her. And I just looked at it, and I’d shake my head and think, I hope this is a great thing,” says Pascal. “It was to the point that when we would go over there I wouldn’t run over and talk to her or anything. I’d talk to Satchel, but it’s like you don’t even dare talk to Dylan when he’s around.” And was Pascal aware of the rule that Woody was never to be left alone with Dylan?

“It was a really good rule,” she says. “There was no other way she could get away and get out.”

Several times last summer, while Woody was visiting in Connecticut, Dylan locked herself in the bathroom, refusing to come out for hours. Once, one of the baby-sitters had to use a coat hanger to pick the lock. Dylan often complained of stomachaches and headaches when Woody visited: she would have to lie down. When he left, the symptoms would disappear. At times Dylan became so withdrawn when her father was around that she would not speak normally, but would pretend to be an animal.

On August 4, Woody was in Connecticut to visit the children, and Mia and Casey went shopping, taking along Mia’s two most recently adopted children—a blind Vietnamese girl named Tam, 11, and Isaiah, a seven-month-old black baby born to a crack-addicted mother. While they were gone, there was a brief period, perhaps 15 minutes, when Woody and Dylan vanished from sight. The baby-sitter who was inside searched high and low for them through the cluttered old farmhouse, but she couldn’t find them. The outside baby-sitter, after a look at the grounds around the house, concluded the two must be inside somewhere. When Mia got home a short time later, Dylan and Woody were outside, and Dylan didn’t have any underpants on. (Allen later said that he had not been alone with Dylan. He refused to submit hair and fingerprint samples to the Connecticut state police or to cooperate unless he was assured that nothing he said would be used against him.) Woody, who hated the country and reportedly brought his own bath mat to avoid germs, spent the night in a guest room off the laundry next to the garage and left the next morning.

On August 4, Woody was in Connecticut to visit the children, and Mia and Casey went shopping, taking along Mia’s two most recently adopted children—a blind Vietnamese girl named Tam, 11, and Isaiah, a seven-month-old black baby born to a crack-addicted mother. While they were gone, there was a brief period, perhaps 15 minutes, when Woody and Dylan vanished from sight. The baby-sitter who was inside searched high and low for them through the cluttered old farmhouse, but she couldn’t find them. The outside baby-sitter, after a look at the grounds around the house, concluded the two must be inside somewhere. When Mia got home a short time later, Dylan and Woody were outside, and Dylan didn’t have any underpants on. (Allen later said that he had not been alone with Dylan. He refused to submit hair and fingerprint samples to the Connecticut state police or to cooperate unless he was assured that nothing he said would be used against him.) Woody, who hated the country and reportedly brought his own bath mat to avoid germs, spent the night in a guest room off the laundry next to the garage and left the next morning.

That day, August 5, Casey called Mia to report something the baby-sitter had told her. The day before, Casey’s baby-sitter had been in the house looking for one of the three Pascal children and had been startled when she walked into the TV room. Dylan was on the sofa, wearing a dress, and Woody was kneeling on the floor holding her, with his face in her lap. The baby-sitter did not consider it “a fatherly pose,” but more like something you’d say “Oops, excuse me” to if both had been adults. She told police later that she was shocked. “It just seemed very intimate. He seemed very comfortable.”

As soon as Mia asked Dylan about it, Dylan began to tell a harrowing story, in dribs and drabs but in excruciating detail. According to her account, she and Daddy went to the attic (not really an attic, just a small crawl space off the closet of Mia’s bedroom where the children play), and Daddy told her that if she stayed very still he would put her in his movie and take her to Paris. He touched her “private part.” Dylan said she told him, “It hurts. I’m just a little kid.” The she told Mia, “Kids have to do what grown-ups say.” Mia, who has a small Beta video camera and frequently records her large brood, made a tape of Dylan for Dylan’s psychologist, who was in France at the time. “I don’t want to be in a movie with my daddy,” Dylan said, and asked, “Did your daddy ever do that to you?”

According to people close to the situation, Mia called her lawyer, who told her to take Dylan to her pediatrician in New Milford. When the doctor asked where her private part was, Dylan pointed to her shoulder. A few minutes later, over ice cream, she told Mia that she had been embarrassed to have to say anything about this to the doctor. Mia asked which story was true, because it was important that they know. They went back to the doctor the next day, and Dylan repeated her original story—one that has stayed consistent through many tellings to the authorities, who are in possession of the tape Mia made. The doctor examined Dylan and found that she was intact. He called his lawyer and then told Mia he was bound by law to report Dylan’s story to the police.

Mia, who never sought to make the allegations public, also told Dr. Coates, who is one of three therapists Woody Allen has seen on a regular basis. Coates too told Mia that she would have to report Dylan’s account to the New York authorities, but that she would also tell Woody. Mia burst out crying, she was so afraid. Ironically, the next day, August 6, Woody and Mia were supposed to sign an elaborate child-support-and-custody agreement, months in the negotiating, giving Mia $6,000 a month for the support of Satchel and Dylan and 15-year-old Moses, the other child of Mia’s whom Woody had adopted on December 17, 1991. Mia believed Woody’s sessions with Dr. Coates had definitely improved his demeanor with Dylan, but because of her concern about Woody’s past history, she had insisted that he not have unsupervised visitation until Dylan and Satchel were through the sixth grade, and that he no longer be able to sleep over at her country house, as he had so far insisted on doing, but stay in a guest cottage across the pond.

One of Mia’s lawyers, Paul Martin Weltz, notified Woody’s lawyer J. Martin Obten of an incident by hand-delivered letter. On August 13, Allen’s lawyers responded with a jolting pre-emptive strike. They filed a custody suit against Mia Farrow, charging that she was an unfit mother. They have also denied any suggestion of child abuse or therapy for it.

In Houston the week Mia and Woody’s problems surfaced publicly, the Republicans at their national convention were unsheathing rhetorical swords to do battle over family values. But the war over the meaning and value of family between Mia Farrow and Woody Allen knocked George Bush and Dan Quayle off the covers of both Time and Newsweek.

Woody told Time, “Suddenly I got a memo from her lawyers saying no more visits at all. Something had taken place. When I called Mia, she just slammed the phone. And then I was told by my lawyers she was accusing me of child molestation. I thought this was so crazy and so sick that I cannot in all conscience leave those kids in that atmosphere. So I said, I realize this is going to be rough, but I’m going to sue for custody of the children.”

The stage was set for a gripping morality play starring two people so famous that they are routinely referred to by their first names the world over. Their reputations and careers were suddenly at stake, and the lives of innocent children and a young college student were caught in the cross fire. Woody Allen maintained he had done nothing wrong, but suddenly he was under criminal investigation because of statements Dylan had made. Things had begun to unravel seven months earlier, when Farrow discovered that Allen was having an affair with her 19- or 21-year-old adopted Korean daughter, Soon-Yi. Was it incest? Mia Farrow believed Allen to be a father figure to 9 of her 11 children, not just to Satchel and the 2 he had adopted, and felt that his behavior could not be excused or rationalized.

Farrow—who, contrary to Allen’s subsequent assertions that their relationship was nearly over by January, still thought they would be spending the rest of their lives together—made the discovery of Allen’s affair with Soon-Yi when she found a stack of Polaroids taken by him of her daughter, her legs spread in full frontal nudity. Woody would later say publicly that the pictures had been taken because Soon-Yi was interested in modeling. Mia found the pictures while she was in Woody’s apartment waiting for one of the children to complete a play-therapy session with a psychologist. (Until recently, Allen paid for all these shrinks; therapy was considered “a family tradition.”) The pictures were under a box of tissues on Allen’s mantle. Each managed to contain both her daughter’s face and vagina, and when Mia saw them, she later told others, “I felt I was looking straight into the face of pure evil.”

‘The charges will never go forward. Woody will be cleared of all that, he’ll see his kids, they’ll come to some settlement,” says Letty Aronson, Woody Allen’s sister, who categorically denies that Woody was ever in therapy for inappropriate behavior toward Dylan, or that he ever favored Dylan over Satchel. “He’ll be the giant in the industry he is,” she continues, “and she’ll be exactly what she is—in my opinion, Woody notwithstanding—a second-rate actress, a bad mother, a completely dishonest person, and someone who is operating completely out of vindictiveness.”

Those close to Allen have insisted that the alleged incident with Dylan described above never occurred, and that the longest period of time unaccounted for on the afternoon of August 4 was less than five minutes, although a principal involved has given an affidavit to Connecticut police stating clearly that the time was at least twice that long. Woody’s lawyers say that he has passed a lie-detector test, and Woody’s side charges that the videotape is suspect because it was made in a series of stops and starts. They also maintain that Dylan’s story is either a fabrication of Dylan’s or a fabrication of Mia’s that she talked the little girl into telling. They say that Mia favors her own biological children, and that once Woody’s son, Satchel, was born, Mia lost interest in Dylan, and Woody took up the slack of parenting. They point out that Mia wrote a glowing letter to the judge in favor of Woody’s adopting Dylan and Moses only a short time before she discovered that he was “taking Soon-Yi out.” (According to Paul Weltz, who handled the adoptions, “There was no glowing letter. It was an affirmative affidavit consenting to the adoption, but at all times reserving her rights as a custodial parent.”)

“I didn’t find any moral dilemmas whatsoever,” Woody told Time about his relationship with Soon-Yi. “I didn’t feel that just because she was Mia’s daughter, there was any great moral dilemma. It was a fact, but not one with any great import. It wasn’t like she was my daughter.”

Nothing could have hurt Mia Farrow more. Having been born to privilege in old Hollywood, she was carrying on a family tradition by acting, but she had also grown up one of seven children in a very Catholic and peripatetic household. The ideal of family, in theory at least, was sacred, but she and her siblings were often left with nannies, and the family later had problems with alcohol and drugs.

Mia Farrow’s mother, Maureen O’Sullivan, was a beautiful movie star, most famous for playing Jane to Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan, and her late father, John Farrow, whom Mia adored, was a screenwriter and director, who had his greatest success as the author of the best-selling inspirational book Damien the Leper, which went through 33 printings. Along with being celebrated for having a roving eye, he was knighted by the pope for his erudite history of the papacy, Pageant of the Popes. The family lived on an enormous lot in an exclusive Beverly Hills neighborhood, and they had a beach house in Malibu and later an apartment in Manhattan. The children also resided with their parents on location in Spain and England, and Mia was educated in a convent boarding school in London. Her brother John recalls that as a child Mia identified with Wendy in Peter Pan, who mothers a gang of lost boys. “We lived in a tall row house in London, which made it seem very real.” At nine, Mia was stricken with polio; her toys had to be burned, and the little girl in the iron lung next to hers in the hospital died. Every Christmas after she recovered, she put on a play starring her brothers and sisters and the neighborhood children—the sons and daughters of producer Hal Roach and actor MacDonald Carey—and charged one-dollar admission. The money was donated to a polio fund.

“Mia was a mother figure in the family. She tended to be in charge,” says Mia’s oldest friend, Maria Roach. “With her family she’s tried to achieve more of a Norman Rockwell experience, with her kids around her all the time. Deep down, we all just wanted to be more normal.”

“There was nothing fragile about Mia,” her mother says. And nothing remotely conventional. By the time she was 18 she was a porcelain beauty eating butterflies at the St. Regis hotel with her dear friend Salvador Dalí. At 19, as a budding flower child and ingénue star on the most popular prime-time soap of the mid-60s, Peyton Place, she made sure she caught the eye of 49-year-old Frank Sinatra on the Fox set one day and promptly flew on his jet to Palm Springs for the weekend. About a year later, her mother got a frantic phone call from one of her neighbors in New York: “Mrs. Basil Rathbone. She said, ‘Something terrible has happened to Mia.’ I said, ‘Tell me what. Is she dead?’ ‘No, she’s married to Frank Sinatra.’ ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘is that all.’ ”

The marriage started falling apart when Mia landed the starring role in Rosemary’s Baby, made by the hot new director Roman Polanski. When they divorced in 1968, Mia astounded Sinatra by not asking for a penny of alimony. (After hearing of her recent troubles, the crooner, who still has a soft spot for Mia, called her up and offered her help and money.) In 1969, Mia herself was the younger woman who broke up a marriage; she became pregnant with twins by André Previn when he was principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra. With their marriage and the arrival of the twins, Mia found what gave her the greatest joy in life: mothering. The marriage lasted 10 years, during which the couple produced another biological child and adopted three others. Previn pays child support and half the tuition for their children.

Previn has also been supportive of Mia, and has told friends, “If Mia is not a good mother, then Jascha Heifetz didn’t know how to play the violin.” Ironically, Woody Allen in the recent past praised Mia specifically as a mother. He told Eric Lax, the author of his 1991 biography, “She has raised nine children now with no trauma, and has never owned a thermometer. I take my temperature every two hours in the course of the day.”

Little Allen Konigsberg (Woody’s real name) didn’t grow up surrounded by stars the way Maria de Lourdes Villiers Farrow did. But for 12 years they shared a life—she starred in 13 of his films—and he credited their time together with opening him up to understanding fatherly love. “Mia’s been a completely different kind of experience for me, because the predominant thing has been family,” Woody told Lax. “She’s introduced me to a whole other world. I’ve had a child with her, and we’ve adopted one. She’s brought a completely different, meaningful dimension to my life.” Two years later, Woody Allen and Mia Farrow are locked in ugly and hurtful conflict. Eric Lax now says, “I find it baffling. Up to the time I finished the book the relations between them seemed very solid, and the relations with the children seemed perfectly normal. I’m crushed for all of them.”

The crisis was shattering for Mia, who would rant on the phone at all hours to Woody, who, her friends insist, kept begging her to take him back. Finally, the endless back-and-forth ambivalence and denial that had gone into attempts at reconciliation came to an end in August. Allen and his friends not only mounted an aggressive campaign of damage control but sought to defend him by painting Farrow, whom he had never moved in with, as filled with rage and out for revenge, hysterical, a compulsive adopter of damaged children who were living out their days in a latter-day version of Miss Hannigan’s orphanage. Chaos reigned at Mia’s house, according to Woody’s side; several teenage children were hinted to be seriously out of control. Woody’s supporters, many of whom have depended upon him for their living, claimed that Mia had turned her older adopted Asian daughters into housemaids, favored her biological children, and beaten Soon-Yi, even breaking a chair on her.

Particularly vicious were the tabloid Hamill brothers, Pete in the New York Post and Denis in the New York Daily News, whose brother Brian has worked for Woody as a still photographer on 17 movies. In a single column, Denis incorrectly charged that Mia “breast-fed Satchel until he was 3½ and even had a special harness constructed to do so over Woody’s objections.” He quoted Woody minions who said that Mia washed down tranquilizers and antidepressants with abundant red wine, and that in April, after quarrelling about his affair with Soon-Yi, she had staged a fake suicide attempt in Woody’s apartment. What had Woody done, was the leitmotif, to deserve all this?

The publicly reclusive director called his first press conference in years at the Plaza hotel to deny the charges. He told the world of his love for Soon-Yi, a sophomore at Drew University in New Jersey, “who continues to turn around my life in a wonderfully positive way.” Revenge for his being attracted to the “lovely, intelligent, sensitive” Soon-Yi—to whom, he explained in subsequent interviews, he had hardly spoken since she was seven or eight, and to whom he had never been any sort of father figure (“She’s probably more mature than I am”)—was the reason, Allen implied, for Farrow’s having made such irrational and outlandish claims as that he had abused his beloved kids Dylan and Satchel. (If rumors existed about Satchel, he had never been publicly mentioned by the authorities or Farrow.)

Less than a month before Mia discovered the photos, Woody had formally adopted Dylan and Moses, but he now spoke of their romantic relationship as if it had ended long ago—apparently news to Mia and friends who continued to see the couple. “I had dinner with them on October 28. Everything was just the same. Woody spent the whole night talking about the adoption—that he was willing to move hell and high water to get it through,” says playwright and lyricist Leonard Gershe, one of Mia’s closest friends and confidants. “Would you be so anxious to adopt a child with a woman you’re not going to see anymore? And would she have allowed it? Maybe it was over in his mind. It certainly wasn’t in hers,” Gershe adds. “But if it were over, then it makes his eagerness to adopt Dylan even more sinister.”

Soon-Yi issued her own statement to Newsweek, asserting her independence, savaging Mia, and declaring, “I’m not a retarded little underage flower who was raped, molested and spoiled by some evil stepfather—not by a long shot. I’m a psychology major at college who fell for a man who happens to be the ex-boyfriend of Mia.” Soon-Yi declared in writing exactly what Woody had said, that Mia would have been just as upset if he had slept with “another actress or his secretary.”

Mia’s family were astounded by the statement. “Soon-Yi doesn’t know half those words, what they mean,” one close to them said. Equally astonished was Audrey Seiger, who has a doctorate in learning and reading disabilities and had spent hundreds of hours tutoring Soon-Yi from the sixth grade all the way through high school. When Soon-Yi was in the third grade, her I.Q. tested as slightly below average. She went to Seiger with “very deprived early language development, which carried on throughout the years.” Seiger and Soon-Yi became close, and Soon-Yi worked very hard. “She’s a very typical L.D. kid, very socially inappropriate, very, very naïve,” says Seiger, who is deeply worried about Soon-Yi today. “She has trouble processing information, trouble understanding language on an inferential level. She’s very, very literal and flat in how she interprets what she sees and how she interprets things socially. She misinterprets situations.” Seiger doubts that Soon-Yi could have written the statement to the press. “The words were often exactly the same as Woody Allen’s, if you compare the two,” says Priscilla Gilman, daughter of Yale drama-school professor Richard Gilman and literary agent Lynn Nesbit and an honor student at Yale, who as the longtime girlfriend of Mia’s son Matthew Previn is regarded almost as a daughter in the family.

After Woody Allen volunteered and gave “exclusive” interviews to both rival newsweeklies, People also produced a cover story and a follow-up the next week. “The media, to my mind, appear to be reporting Mia Farrow’s [responses] … and looking at them as if they are on par with Woody Allen’s having an affair with her daughter,” says Dr. Kathy Weingarten, a Boston family therapist who is writing a book on changes in modern motherhood. “[Her reactions] are looked at as if they are morally equivalent. I find that troubling.”

Mia declined all offers of interviews giving her equal time, although she did speak briefly to Newsweek about her family. Diane Sawyer was willing to give her a whole show, Barbara Walters was ready to hop a plane back from Italy, Maury Povich even sent flowers to one of the baby-sitters. Several of Mia’s children, however, elected to give statements in support of her, which led to charges by Woody that she was “parading” her children to the press in an unseemly fashion. It didn’t help that Maria Roach read a letter from Mia—with Mia’s permission, she said—to an A.P. reporter in Los Angeles. In the letter, Mia confessed that she had come to a “genuine meltdown.” “Mia was sobbing when that letter was released,” says Priscilla Gilman. “I spoke to her, and she said, ‘I’m so humiliated, I can’t believe this—and she’s saying I authorized this.’ ” “I just read it to show she has all her faculties and that she had been dealt a terrible blow,” says Roach. “I read the letter thinking he would paraphrase it. In the end it was misquoted.”

Most damning was the implied belief in Soon-Yi’s statement to Newsweek that it was Mia or someone close to her who had got a copy of Dylan’s videotape into the hands of New York’s Fox Channel 5 news. Both Mia and her mother denied the charge. The tape never ran, but the station did not exonerate Mia of leaking it. Reporter Rosanna Scotto says, “I wish we could,” but to do so would “narrow the field” among the possible suspects.

By not tightly controlling all statements in the beginning, Mia’s side made some clunky missteps that Woody’s side offered as proof of her irrational rage. Mia told friends that he seemed to be following through on a threat she said he had delivered a few days before August 4, as word of the affair with Soon-Yi began to leak out. When Mia refused to appear at a proposed press conference called in part to say there was nothing at all between him and Soon-Yi, he reportedly told her that if the story ever came out he was going to say he loved Soon-Yi—making good on what he had previously threatened, that by the time he was finished with Mia there would be nothing left standing.

‘It’s a classic case of a woman scorned,” says Jane Martin, a close friend of Woody’s who worked as his assistant in the 1980s. “I’ve never been chewed out like I was by Mia. She can go from zero to 100 miles an hour in one second. She went berserk screaming crazy at me for two situations I had nothing to do with.” Martin, who is convinced Mia favors her natural boys over her adopted girls, likens her presence to “having a huge cobra coiled up in the corner of the room and having to watch it every day so it wouldn’t come out.” Martin also thinks that Mia’s “revenge” has been successful. “She’s put an indelible black question mark at the end of Woody’s name forever.”

Mia Farrow not only felt massively betrayed but also was terrified that Woody Allen was coolly and deliberately tearing her family apart. In spite of everything, she had been holding her breath and hoping that the agreement would be signed. She was dependent on him both emotionally and financially. Although Variety recently reported that “Woody Allen makes expensive pictures and demands a rich deal,” all she reportedly earned from Allen was a modest $200,000 per film. Woody Allen is one of those rare auteurs in the film business who has had to answer to no one, and Mia enjoyed the security he provided. “One of the things that happened to Mia,” says Lynn Nesbit, “is that she got cut off, too.”

To close the nightmare down, a few days before the Newsweek and Time cover stories came out, Mia told friends, Woody had agreed to drop the custody case and sign the original agreement if Mia would say she was dropping the abuse charges and the family would deal with the issue privately. “I think Woody’s big thrust is: You poisoned the atmosphere so much that Dylan’s making this thing up,” says Lynn Nesbit. Thus, an eyewitness who has given an affidavit to police says, Mia went to Dylan to see if she was willing to recant. Mia said, “Dylan, you know, we all make up stories. Everybody does that. Sometimes we know we made it up.” But the little girl would not back down. “If he says he didn’t,” Dylan answered, “he’s lying.”

An individual close to Woody denies that Woody ever suggested such a compromise, countering, “That original agreement was old news. Mia had no options of taking it back—none.”

Since the incident, Dylan has burst out, even in the middle of playing games, with statements like “I don’t want him to be my daddy.” “The thing that people have to understand in this case is that it is not Mia versus Woody; it’s just a plain simple fact that a seven-year-old child has told her mother something and that her mother has to choose to believe her,” says a member of the household. “If her mother doesn’t believe her, who is going to believe her?” Lynn Nesbit observes, “Mia says, ‘How can you turn your back on a seven-year-old?’ Believe me, her life would be a heck of a lot easier if she dropped it.”

Over the years Mia had turned down other directors’ offers to act—including the role in Father of the Bride played by Diane Keaton, Woody’s ex-girlfriend—in order to stay in New York with her family and appear only in films by Woody. “Mia told me he was always telling her she had no talent at all,” says Leonard Gershe. “She was only good in his pictures, not anybody else’s. Nobody would ever hire her again.” Mia, who throughout their relationship had endured blistering put-downs by Woody—she told friends he once lit into her in front of the Russian Tea Room because she was off four degrees on the weather, and another time because she was unable to tell him how many kinds of pasta there were in the world—now so feared Woody that some of her behavior was classic textbook “female victim.” For example, when the Connecticut police asked her for Woody’s home-phone number, she refused to give it to them. The police just laughed at her.

To those on the inside, however, who have watched the departure of Soon-Yi from the family, who have heard Dylan on the videotape and seen her changes of behavior, who have read the lurid headlines about Mia, who know about another approach Woody apparently made within the family, and who wonder if their phones are being tapped, Woody Allen is a chilling figure of power, a potentate of reel life who doesn’t seem to have to play by the rules. “This man is so exalted in the business—no one has the position he has. Until recently he hasn’t had to submit a script or anything,” says Leonard Gershe. “I think when you get up into that stratosphere you no longer have to pay attention to the law of gravity. Regular morals, conscience, ethics—that’s for slobs like you and me.” The effect, says Gershe, “spills over into real life. He’s treated like a little god, and little gods don’t have to do what everybody else does.” “He just scares me,” says a member of the household. “I think he scares everyone who knows all the things he has done. And anybody who is close to him—that he has the potential of destroying—I think is scared of him.”

That includes most of the members of Mia’s unconventional family. “She’s afraid that he’s going to be gunning for her kids,” says Gretchen Buchenholz, a friend of Mia’s who heads the Association to Benefit Children and has helped Mia to find children to adopt. “He hasn’t done everything yet.” Mia’s twins by André Previn, Sasha and Matthew, are now 22. Sasha is in his last year at Fordham, and Matthew has graduated from Yale and is studying for his law boards. Mia and André Previn’s next child was adopted, a Vietnamese orphan named Lark, 19, who is now in nursing school at New York University. She has always been the one, those who know the family say, who likes to cook and care for her brothers and sisters. Mia then became pregnant again, with Fletcher, 18, now a senior at the prestigious Collegiate School. As Vietnam crumbled, André and Mia were able to get their daughter Daisy, 18, out on the last plane. Daisy was so malnourished and her intestinal lining was so damaged that she had to be fed at first through a tube in her head. She is now an honor student who won a math prize at another posh New York prep school, Nightingale-Bamford. Soon-Yi came at around age seven, just as André and Mia were ending their marriage. Six of Mia’s 11 children, therefore, are quite grown-up.

Moses, from Korea, who has made great strides in overcoming his cerebral palsy, is 15, in the ninth grade at the exclusive Dalton School. Dylan is at Brearley, considered one of the top girls’ schools academically in New York, and Satchel goes to a Montessori pre-school. Tam, who is still learning English, is in a special-education class at P.S. 6, one of the best public schools in the city, and the baby, Isaiah, seems no longer to have any symptoms of cocaine withdrawal.

In various interviews, Woody or his supporters have mentioned shoplifting, truancy, turnstile jumping, and check forgery as the dirty secrets of Mia’s kids. According to those close to the family, two years ago Lark and Daisy and two of their friends were picked up for shoplifting some underwear from a Connecticut mall. Around four years ago Lark got caught jumping a subway turnstile going home from a party that she had sneaked out to. Last year, Daisy, who hadn’t yet received her monthly allowance check from André Previn, forged Soon-Yi’s signature on hers while Soon-Yi was away at school. She was immediately made to pay the money back. Daisy also skipped five days of school last year when Mia was in Vietnam to arrange for an adoption.

“Most of my students are New York City kids. Many have parents who are glamorous and famous, and most of these kids are very neglected and troubled and grow up very fast,” says Audrey Sieger, who has been tutoring the children in the Previn-Farrow-Allen household for the last 12 years. “Mia’s family is very unusual. She—at any time in these 12 years—has been able to tell me in detail about every one of her kids. These kids travel on buses with bus passes. They cook dinner for each other. They do their own laundry. Different kids over the years have been assigned the job of going to the supermarket. They have not been raised by nannies.” Mia, according to Sieger, was “warm, loving, sincere, and throughout all my years of working with the kids, having them at my office, calling at home, they were happy kids, giggling and laughing and involved with each other.”

“I couldn’t get over how much the biological kids weren’t favored. They all viewed each other as equal and always referred to each other as ‘my brother,’ ‘my sister,’ ” says Lorrie Pierce, who has gone to the house to teach the children piano for the last seven or eight years. “Mia passes down family heirlooms to each one, without regard to who is adopted.” The piano teacher echoes the tutor: “She’s the one that kids threw up on. She gets right in the arena and does all the dirty work. She doesn’t push them off onto the help.” Every September, Mia would start a new film with Woody, and, according to those in the household, there was rarely a day when at least one of the children didn’t accompany her to the set; she turned her dressing room at the Kaufman-Astoria Studios into a nursery for them. Creating a large family “is not the act of a compulsive. It’s too much hard work,” says Mia’s friend Rose Styron, the human-rights-activist wife of novelist William Styron, who is Soon-Yi’s godmother. “I’ve never known anyone who cared so selflessly about children, and who put so much of herself into them.… They always came first.” Perhaps that was the key issue for Woody: who came first? One of the people who has spoken up for him, his costume designer Jeffrey Kurland, said in New York magazine, “Why this constant need [of Mia’s] for infants and little ones? Get on with your life!”

Tisa Farrow says, “That is her mission in life. Her vocation is her work as an actress; her vocation makes her mission possible.” Leonard Gershe says, “Mia told me long ago, when she was adopting the fifth or sixth child, ‘Lenny, I was so lucky to find out fairly young that pink palazzos and swimming pools were never going to fulfill me. They don’t do it for me. I’m not interested in fashion, I’m not interested in jewelry. I’m interested in giving a life to someone whose life would not exist if it weren’t for me.’ What’s so terrible about this? It’s absolutely sincere.”

Throughout this ordeal Mia’s other children have been loyal to their mother; none of her older children any longer speaks to Woody. They appear to be furious that he has said that he was never any sort of father figure or figure of authority for them, and that they wouldn’t have cared two seconds that he was having an affair with Soon-Yi if Mia hadn’t kept them whipped up. “The insensitivity of someone who could say that brothers and sisters would not care that their mother’s boyfriend was having an affair with their sister … devastated the entire family,” says Priscilla Gilman. “She wasn’t jealous; it wasn’t that at all. It was a sense of moral outrage.”

Soon-Yi has reportedly told her mother that she doesn’t need her anymore. For the time being, Soon-Yi is out of the family. Woody pays her tuition at Drew, where his limousine has been seen picking her up on Fridays. The empty space at the dinner table at Mia’s where Soon-Yi used to sit has been taken up by Isaiah’s high chair, although all in the family insist they still love Soon-Yi and want her to come back.

Both Woody Allen and Mia Farrow had to make strenuous efforts to get these children: a New York adoption law had to be stretched for Woody to adopt Dylan and Moses, but it required an act of Congress for Mia to have Soon-Yi.

For the first three years Mia cared for her, Soon-Yi referred to her as “Good Mama,” as opposed to her natural mother, “Naughty Mama.” Naughty Mama was reportedly a prostitute; for punishment, she would force Soon-Yi to kneel in a doorway, and she would slam the door against the little girl’s head. One day she left the child on a street in Seoul and said she would be back in five minutes. Then she disappeared forever. When the orphanage found Soon-Yi, she spoke no known language, just gibberish.

Mia waited almost a year to get her, and finally had to request that Congress change the law that limited the number of alien children an American family could adopt. She then stayed at the orphanage in Seoul washing dishes for 10 days until Soon-Yi’s papers came through. In order to get to know the child, Mia brought her a doll and a pretty new dress. The doll frightened Soon-Yi. She had never seen one before and thought it was some kind of animal. Later, when Mia dressed her up and stood her before a mirror, Soon-Yi hated what she saw and tried to kick the mirror in. She despised men more, and hissed whenever one came near. Recently, a psychiatrist who has seen Soon-Yi informed Mia that mothering her was probably a no-win proposition: in terms of transference, her intense antipathy toward her biological mother was too great. Mia’s friends say Mia disagrees with this assessment.

At some point Soon-Yi started calling “Good Mama” Mia. “She was not as close to Mia as the other children were,” says Priscilla Gilman. “She wasn’t very demonstrative. Mia was towards her, but she just never was towards Mia.”

Nobody knows how old Soon-Yi really is. Without ever seeing her, Korean officials put her age down as seven on her passport. A bone scan Mia had done on her in the U.S. put her age at between five and seven. In the family, Soon-Yi is considered to have turned 20 this year, on October 8. Prior to Tam, she was the oldest child Mia had adopted; she was also the most learning-deprived, the quietest and least socialized of all the children. She has always worked extraordinarily hard, spending hours on homework it took others a half-hour to complete. Because of her learning disabilities, she took the S.A.T.’s untimed.

At Marymount, a parochial school that Buchenholz says has had outstanding success with a “heterogeneous system which mixes girls like Soon-Yi with National Merit Scholars,” Soon-Yi was so upright the family thought she might want to become a nun. “She was very straitlaced, very, very proper—morally,” says Audrey Sieger. “That was the shock for me: she’s so very moral about anybody who would cheat on a test or take a shortcut to do something.”

Soon-Yi shared a room with Lark and Daisy, both of whom were far hipper and more outgoing than she. Soon-Yi seemed to live in a world of fairy-tale romance, dreaming of boyfriends who never called. She had a picture of Fred Astaire next to her bed. “My personal opinion is that she’s basking in the sunlight of the attention,” says Sieger, “kind of like she’s in a romance.”

Soon-Yi and Lark were paid $70 by Woody to baby-sit on alternate weekends for Dylan and Satchel—an arrangement Soon-Yi and Woody’s side are now using as evidence of Mia’s making servants of the children. “I felt it was kind of tough on them,” says Sieger. “It was like a 24-hour deal, watching babies.” One summer Woody got Soon-Yi a part as an extra in Scenes from a Mall, the film he starred in with Bette Midler. Soon-Yi entertained thoughts of being a model and in her senior year Woody advised her on how to go about it. “Those last six months of high school, there was a definite change. I have no idea when her relationship started with him,” says Sieger. “He was helping her to show her how to dress and prepare herself to be a model, and he arranged for her to have professional pictures taken. When I saw the professional pictures, I was very surprised, because Soon-Yi looked so glamorous.”

The family soon sensed that Soon-Yi had a crush on Woody, which he seemed to delight in. But they thought nothing of it, since Soon-Yi had yet to receive her first phone call from a boy. Woody started taking her to basketball games, and Mia would reportedly tell her to stop dressing up for them as if she were going to a disco. The summer of ’91, Soon-Yi stayed in the city to work. She lived in Mia’s apartment with her big brother Matthew, whom she idolized, while Mia and the younger children were in the country. At night she would get all dressed up and go out, never telling Matthew or Priscilla where she was going.

“All of a sudden she started wearing these incredibly sexy clothes, and putting on these black, really slinky shirts and little skirts and these pumps and stuff,” says Gilman. “She would say, ‘Don’t tell Mom. I’m going to a friend’s house.’ And I said to Matthew, ‘I think she has a secret boyfriend, and I think we should find out who this is.’ And Matthew said, ‘Oh, no, just let her do her own thing.’ Matthew is very into respecting people’s privacy, and I said, ‘No, Matthew, as a good brother you should find out who this is. This is rather odd that she’s slinking around like this.” And he said, ‘No, no, no.’ ” Soon-Yi’s other brothers and sisters also noticed things. Once, Moses told a family member he had seen Woody looking up Soon-Yi’s skirt right in the apartment, and Daisy was surprised to find him another time touching Soon-Yi’s hips, but the two kids didn’t dwell on these things.

Around last Thanksgiving-time, a few weeks before Woody’s formal adoption of Moses and Dylan was to become final, a time when members of the family now feel he was probably involved with Soon-Yi—Leonard Gershe says Mia told him both Soon-Yi and Woody told her on the day she found the pictures that they had been seeing each other for about six months and that the relationship had become sexual about the first of December—Woody also began to take a special interest in Daisy. Four different times, according to several sources, he tried to engage her in intimate conversation, asking her to tell him all her secrets, things she wouldn’t tell her mom about a boyfriend, asking, Where do you go at night—do you sneak out? Daisy, according to those close to her, couldn’t figure out if he was trying to become more of a father figure or “some cool friend or what.” “But she didn’t tell Mia at the time, because Mia would be hurt,” says Gershe. When Woody saw Daisy defend her mother in the media, he reportedly called her “a lying little twit,” and threatened that he’d see her in court.

Despite more than 20 years of analysis, Woody Allen seems to keep repeating himself. And right up to Husbands and Wives, which Mia had no idea was such a close parallel to them, he seems deliberately to have tried to work out his real life in his films. “Substitute Mia and her daughters for Hannah and her sisters and you begin to understand what this man is about,” says Leonard Gershe.

Once Mia found the pictures, life for the two took a different course, and would never be the same again. But from the beginning, Woody Allen has seemed curiously numb to the moral implications of his relationship with Soon-Yi, unwilling to recognize the effect his behavior has on others. “To this day I don’t think he really understands what everybody’s so excited about,” says Leonard Gershe. “He does not understand the morality of it. He’s deflecting things with ‘She’s over 18.’ Nobody ever questioned that he did anything illegal. He did something immoral, and that’s what he can’t understand.” “He didn’t see how traumatic this was to the family,” says Lynn Nesbit. “He saw it as something traumatic a man had done to a woman. He couldn’t acknowledge it. He wouldn’t.”

Mia called Gershe from Woody’s apartment the day she discovered the photos. “Her voice was shaking, and I knew something god-awful had happened.… She said, ‘I can’t believe this. I have nude pictures of Soon-Yi.’ ” Mia then phoned Woody and told him she had found the pictures and “to get away from us.” She grabbed her child and went back to her apartment. Soon-Yi was there, still at home on her Christmas break. A donnybrook ensued. Mia slapped Soon-Yi four or five times over a few days. Woody said that Mia locked Soon-Yi in her room and also smashed her with a chair, but one eyewitness denies it. “I was over there the next say,” says Casey Pascal. “The room wasn’t locked, and I never saw any bruises or anything [on Soon-Yi].”

Woody came over immediately. He first told Mia that he loved Soon-Yi and would marry her. “Fine,” Mia said. “She’s in her room. Take her and go. Get out of here, both of you.” Then, Mia told friends, Woody dropped to his knees and started to cry. He begged Mia’s forgiveness and asked her to marry him—“put this behind us, use it as a springboard to a better relationship.” He called what had happened with Soon-Yi “a tepid little affair that wouldn’t have lasted more than a few weeks anyway.” He also told Mia that the affair was “probably good for Soon-Yi’s self-esteem.” “His whole attitude about it was as though it were a breach of etiquette—he used the wrong form: So let’s put that behind us. It’s embarrassing, but, you know, let’s get married,” says Leonard Gershe. “She couldn’t believe what was coming out of him. And then she slapped him.” Nevertheless, Woody spent the dinner hour with the children as usual.

The next day Mia asked Casey Pascal to go to Soon-Yi. “ ‘I’m too angry to talk to her, but go in and make sure she knows that I still love her.’ And I went in carrying that message,” Pascal recalls. “Soon-Yi just cried and said, ‘I didn’t mean to hurt my mother.’ And I said, ‘What did you think was going to happen?’ And she said, ‘I never thought she’d find out.’ ” Soon-Yi would not hear of any of its being Woody’s fault. “He’s not to blame for this,” she told Pascal, and admitted that their affair had begun in the fall. “She was saying things like ‘My mother didn’t understand him—she didn’t have time for him and all his needs.’ The child was absolutely tortured, and she was totally loyal to him.”

When a much younger, less sophisticated person takes a lover the age of a parent, says Dr. Leo Kron, the director of adolescent and child psychiatry at St. Luke’s/Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, “it may create for her the opportunity to avoid the anxiety of normal development. It can be a way to avoid socialization. It’s a safe haven with a parent figure, an escape from the normal vicissitudes of growing up. The fact she had such a deprived early existence makes it more difficult for her to become independent. There’s a greater risk of getting involved in a relationship where she has to be taken care of.”

Soon-Yi’s big confrontation with her family came the following weekend. Most of the children had been in the apartment the previous tense days, witnessing tears and fights, yet Woody blamed Mia for telling them anything at all. “It was her fault they were mad at him,” says Leonard Gershe. That Sunday in Connecticut, while Dylan and Satchel watched The Little Mermaid in the TV room, the older children and Priscilla Gilman and Mia had a family meeting with Soon-Yi. “The whole notion that Mia kicked her out of the house is completely a lie,” says Gilman. “It was a choice. She said, ‘Soon-Yi, we want you in this family. We love you. But you are going to have to choose whether you want to be in this family or to be with Woody. And that you can promise me that you will never do anything like this again.’ ” Then the brothers and sisters spoke, trying to understand what had happened. “All I remember Soon-Yi saying was ‘It’s my fault, it’s my fault, it’s just as much my fault as Woody’s,’ ” says Gilman. Soon-Yi refused to explain anything. “She just ran out.”

Woody, however, according to those close to the family, promised Mia he would leave Soon-Yi alone, and Soon-Yi confided to her mother that he had told her previously to go ahead and meet other boys and sleep with other boys, that their relationship was just a little secret something on the side and not to expect anything to come of it. Not long after, Mia finished her last two days of shooting on Husbands and Wives. “She was in denial, obviously. Her whole life was tied up with this man,” says her sister Tisa Farrow. “He made her feel like she couldn’t live without him. She took a long time to get pissed off. She’s no less vulnerable just because she’s an actress and has money.”

On Valentine’s Day, Mia sent Woody a picture of her and her children, with a toothpick stuck in each person’s chest. The message: “This is how many hearts you’ve broken in this family.” Woody gave her a red satin box filled with chocolates and an embroidered antique heart.

February was an amazing month. A six-year-old Vietnamese boy Mia and Woody had been waiting months to adopt arrived. He was supposed to be recovering from polio, but she soon discovered that he had severe cerebral palsy and was retarded. He screamed all day. She felt the burden of having him was too much for the other children, and after four days she allowed him to go to a family in New Mexico who already had older retarded children and who wanted him very much.

In his place came Tam, an 11-year-old Vietnamese girl who had lost her eyesight from an infection while she was in an orphanage. Woody went to the airport with Mia when Isaiah joined the family the same month. All during the spring, Mia, who would later be characterized in the press by a friend of Woody’s as a heavily medicated, walking zombie, was busily putting together an education program for Tam.

Rose Styron saw Mia in May, when she “was overwhelmed on all fronts, when nothing was sorted out.” Styron saw her again just before Labor Day, in Connecticut, down by the pond happily surrounded by eight of her children. “Tam was speaking English, laughing, standing up straight, showing she could handle things. I couldn’t believe what had happened to Tam in the three months since I’d seen her.”

Nevertheless, Mia had had a bleak spring. She and Woody went round and round about their relationship. She told friends he wanted to come back. She became depressed and sought a psychologist’s help for the first time in her adult life. As usual, Woody paid for the therapy. (“You can’t say his own therapy failed,” quips Mia’s lawyer Eleanor Alter. “He might have become a serial killer without it.”) She was given an antidepressant, which she had a bad reaction to. Reeling from the drug, she had thoughts of suicide and wrote a note to Woody, saying she felt she couldn’t go on. But sources close to her say she tore the note up immediately, and flatly deny that she ever faked a suicide attempt. She then called the doctor, who explained that the drug “sometimes has the reverse effect.” For two months she took a different antidepressant and a mild sleeping pill each night so that she could still wake up to feed the baby, who slept in her room. One night Woody took her to Elaine’s when she seemed particularly low. Leonard Gershe got a report back from friends that “Mia looked like Jackie Kennedy on Air Force One.” In June, she stopped both the therapy and the pills. Since January she has had four panic attacks, and takes medication if one comes on.

Every day the children went through their usual routine. One member of the household staff says about the reports of Mia’s need for pills and alcohol, “How could she have cared for a baby in the evening? How could she have cared for all the children? … I think I would have noticed if she were drinking or taking pills.” Mia told Leonard Gershe of an evening when Woody took her out to an East Side restaurant and they had a fine wine. “He was being particularly sweet and lovely to her, and he said, ‘Mia, we really can put this behind us. Let’s go back to your place, let’s tear up those pictures of Soon-Yi.’ Mia said, ‘I don’t think so.’ ”

In June, Soon-Yi was about to finish school and go to work as a camp counselor for the summer. She hadn’t had much contact with the family—according to someone close to the household, one of the legion of shrinks told Mia it was better for Soon-Yi to remain outside the circle for a time as she was “too sexualized an object.” Mia thought it would be a good idea for her to be with kids her own age, so Soon-Yi took the counselor job at a camp in Maine. But in July, Mia received what Maureen O’Sullivan calls “an awful letter.” The head of the camp had fired Soon-Yi because she didn’t get along with the children, and was concerned that she kept getting phone calls from an older man who called himself Mr. Simon. Mia’s friends say that Woody, who had given his solemn word that he wouldn’t have any contact with Soon-Yi, first denied, then admitted to, the calls, but said he had made them just to be certain Soon-Yi had enough money. Soon-Yi called to say she was going to live at a friend’s but Mia did not know where she was until the tabloids found her, after everything exploded in August.

One of the great ironies of this story is that Woody Allen, by virtue of his vaunted reputation, was able to adopt Dylan and Moses, who had already been legally adopted by Mia in 1985 and 1978, respectively. Never before in New York, it seems, had two single people separately adopted the same children—unmarried couples have not been able to adopt at all—and in fact, had the case been taken to family court, the usual venue for adoptions, such an exception would probably not have been allowed. But their lawyer Paul Martin Weltz put the adoption of Dylan and Moses before Judge Renee Roth in the surrogate court in Manhattan. “Surrogate court is less hectic. I felt the two judges there were both very humane and forward-looking,” says Weltz. “In family court you never know who you’re going to get. I didn’t want some clerk to say, ‘The statute doesn’t permit it. Go away.’ ” But, adds Weltz, “to have a second parent of the intellectual ability and the financial ability of a Woody Allen—how could anybody at that point think of a single negative?”

Given the status of the father, the home study was waived, and the court presumably knew nothing about Woody’s sessions with Dr. Coates. “You have a home visit when you’re thinking maybe these people can’t afford another child. Here there was no issue of morality or finances,” Weltz says. “Woody had told me that he used to go over to Mia’s apartment every day and be there when the children woke up. He’d see them every day in the middle of the day. He’d be there when they went to bed. On the surface it seemed that he was more of a father than a lot of natural fathers I represent.” Weltz recalls December 17, the day Woody, Mia, and the children accompanied him to the courtroom (where Woody remembered he had once shot a scene) and the judge’s chambers, as being “probably the happiest day I’ve ever spent in court.”

Now Mia, who is the one being accused of being an unfit parent, wants the adoptions nullified, and her lawyers are considering going to court to try to overturn them. If they succeed, the custody case would be moot, of course. Meanwhile, authorities in Connecticut are pursuing their investigation to decide whether or not there are sufficient grounds to charge Woody Allen criminally with child abuse. For the last month a team of experts in New Haven have been examining the evidence and listening to Dylan tell her story. If they conclude that there is sufficient evidence to charge Woody, it is still up to the Litchfield County prosecutor to decide whether to proceed with a trial. And if so, will Mia allow Dylan to take the stand? The family says she will. A gripping courtroom drama may be in the making, one that would undoubtedly give tabloid TV its highest ratings ever. Or things could be settled overnight. Left unresolved, however, is the healing process—how Mia and Woody and these 11 children can ever be reconstituted as a family.

In March, Mia Farrow had all of her children who were not Catholics—including Soon-Yi—baptized.

Original Publication: Vanity Fair – November 1992.