Twice in My Life

Maureen Orth

Colombia 1964-1966

My Medellin has never been like the headlines that have been flashing round the world for a decade. The gentle “city of eternal spring,” the capital of the department of Antioquia, that I lived in and cherished for two years in the sixties as a PCV, has been morphed into a violent and bloodthirsty symbol of illicit drug-dealing — where bombs and kidnappings have replaced conservative Catholicism and the Antioquenos long-held reputation for entrepreneurial fervor.

Today the rap on Medellin is horrendous: the U.S. State Department warns Americans that all of Antioquia is off limits for safe travel. Journalists are especially susceptible to guerrilla attack. My Colombian novio of long ago, who had become a Senator, was murdered in 1989 when he refused to give in to a self-styled militia leader who wanted a piece of his land. Amid this turmoil I could only dream of going back to Medellin to visit my Peace Corps site and to see the school that I had helped build.

My memories, of course, were vivid. One Sunday a dramatic posse of five men on horseback dressed in black gaucho hats and traditional wool ruanas galloped up to my door in the barrio. They were leading an extra horse for me. We rode straight up into the mountains for about three miles to meet an isolated community of campesinos in a vereda called Aguas Frias. The people were desperate for a school.

Several Sundays later we began with a community work day and formed a human chain to throw rocks down the mountainside to clear the land. A year later there was a brick building that on dedication day bore a crude hand-lettered sign that was a happy surprise to me: Escuela Marina Orth.

I had not seen the school since 1979. Then suddenly an invitation came out of the blue from “Friends of Colombia,” our in-country group, and I thought that I must go. In the fall of 1995 I became part of an official goodwill tour of Colombia, one of a dozen former Colombia Peace Corps Volunteers graciously invited by the Colombian Ambassador to visit four cities. Medellin was not on the itinerary, but I could easily go there by myself. Things had calmed down, I was told, since the world’s most notorious narcotraficante, Pablo Escobar, had been killed.

Then a curious thing happened: I became afraid of the depth of my own emotions. I couldn’t even think of going back to Medellin without choking up inside. So many intense memories of specific people and the majestic, sweeping Andean countryside came flooding back — not to mention the Spanish language, the music, the freedom of galloping on a horse through grass as high as my shoulders. Of course in those days we called the rain forest the jungle; there were families of fifteen and twenty children, and good girls still courted through grilled windows; the young man wasn’t allowed inside until he had declared. What if what I now saw broke my heart? We all knew the culture minutely; we had such a strong sense of identification with a country completely different from our own, and I was so young then, yet, never afraid of anything — not of living alone in a barrio considered rough, not of the rigid power structure that I believed kept my poverty-stricken neighbors locked in a dead-end destiny, and certainly not of the Peace Corps rules and regulations. The arrogance of youth — just leave us alone to do our work.

About a month before I was due to arrive, I wrote to the Senora Directora of the school at Aguas Frias and had an old friend who lived in the city deliver it for me. She could get there by jeep, my friend reported–the road was now paved and a horse was no longer required.

I didn’t even recognize my old barrio, Las Violetas. Where once you had to cross a creek with water coming halfway up the bus’s wheels to enter, today the creek is gone and the barrio, even more teeming with people and cars — cars! — looks not poor anymore but typical of a Colombian blue-collar neighborhood — an extension of a more prosperous area that used to be a few miles away.

As we climbed the road it was reassuring to see the towering Andes flanking us. The higher we climbed, the calmer I felt. At least the dark green mountains hadn’t changed. And then we turned a curve and the day became magical. Two smiling, scrubbed little school boys in brand new uniforms were out on the road to greet me waving paper Colombian flags.

We parked below and they ran ahead to lead me up the steep steps (another innovation) to the carved-out mountain where we had built the school. “Here she comes!”they cried. At the top of the steps, in tears and hiding her face in her skirt, was my kind neighbor from across the street in the barrio, Dona Mariela–mother of fifteen, grandmother of forty, now widowed, now living close to the school. I too began to cry as I hugged her, the first of many tears that day.

The school looked fantastic. A second story had been added, hanging pots of tropical flowers were suspended from the upper corridor, and just below on the front wall was a big metal sign donated by a local soft drink company that said Escuela Marina Orth. Next to it hung a second, hand lettered sign: “Welcome Home.” Instead of the 35 students in two classrooms that I knew of in the sixties, there were now 120 children in grades one through five. I was amazed and unprepared for the six-hour homage to come.

Slowly and shyly, men and women I had known and worked with came from around corners and behind pillars to greet me. They brought me lemons from their garden. They told me of births and deaths and invited me to their houses. I was most thrilled to hear that some children from the school had gone on to the university and were now professionals working in Medellin, a nearly inconceivable dream when we began. They exclaimed at and eagerly grabbed pictures of my family that I had brought to show them.

Then I saw Luis Eduardo, the humble, soft-spoken president of the vereda’s community action junta and really the co-founder of the school as well. A portrait of us taken together nearly thirty years ago, now tattered, was brought out for our inspection. How many times Luis Eduardo and I had ridden to town together to knock on doors in the city government to beg for bricks and mortar. He was so quietly persistent that he had been hired by the city of Medellin to work in its office of school construction, a big step up for his family.

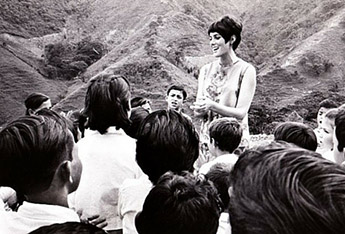

The children, shined up bright, were taking their places outside to raise the flag and sing for me the Colombian and Antioquenan anthems. The principal presented me with a beautiful homegrown arrangement of orchids, lilies and roses, and gave me a formal speech of introduction. With the children standing at attention, she announced a twelve-act program in my honor to be followed by a lunch, a serenade, a toast, and a mass!

I was standing but I felt I should sit. The moment was surreal. It seemed that I could almost touch the other side of the mountain. The populous valley of Medellin was spread out below and I was surrounded by these beautiful children honoring me in a school that bore my name. Was I really in this exotic place on this cool sunny Friday morning so far away from the rest of my life? I missed my family and wished they could share this with me. Nevertheless, I felt completely at home.

At the end, mass in this setting was simple and moving, celebrated by a young priest in white vestments on a makeshift outdoor altar in front of the school.

The mass to me was the most important part of the day. The people’s faith remains strong and as a Catholic myself I felt a special bond in sharing it with them, in having the children come up to touch my hand to wish me peace, and to take communion with them.

I tried to make my fifth speech of thanks and told the congregation that the whole idea of the Peace Corps was to plant the seed so that the community could go on as they had. This was my real thanks — that they had persevered. As I turned to go I realized that at least once in my life, when I was young, enthusiastic and just doing my job, I actually accomplished something that my country and my family could be proud of. And twice in my life, the Peace Corps and the people of Colombia had given me more than I could have ever imagined.