Original Publication: New West Magazine – June 19, 1978

“…Kids whose ideas were shaped by the sixties are beginning to have impact on the lifestyle, movies and morality of Hollywood…”

The paparazzi could see them for blocks. Hundreds of rented limousines—black, blue, green and canary yellow—were creeping into the white glare of searchlights, stopping just long enough to deposit the working industry of Hollywood at the entrance to the Century City entertainment complex. The A list, the B list, the C—for cocaine—list were all turning out for the opening of the Los Angeles International Film Exposition, sauntering from their limos into the waiting flash.

Suddenly the paparazzi began to look confused. Who were some of these people anyway? Like that kid wearing blue jeans with his tux, and an old SDS button. Ron Galella said he heard the kid was running a studio but Ron didn’t believe it. Nevertheless, just to be sure, Ron flashed him with the strobe. The kid was followed by an even younger guy wearing a weird red-and-white striped shirt and a big Beatles button. The paparazzi didn’t recognize him either. But he, too, was a baby mogul, another of those sixties kids who have recently come to power in Hollywood and will likely set the tone for the movie industry throughout the 1980s.

In the last few months, while most media attention has focused on corporate corruption of the Old Guard, Hollywood, more significantly, has become flush with new blood and money. As happens every four or five years, a new wave is cresting. The seventies began with the ascendancy of agents, packagers and film-school kid directors such as Francis Coppola. The decade was marked midway by creative disappointment as the deal became the art form and the blockbuster mentality prevailed; and now it is ending with the rise of a group of fresh faces whose style has been formed by their common cultural experience of growing up in the sixties. This new breed is young and well educated. Many of them come from radical backgrounds and are trying to resolve their past with their present. Their sensibility is already starting to have some impact on the way people at the top live in Hollywood, on the films we see and, at a most critical time, on the future morality of the movie business.

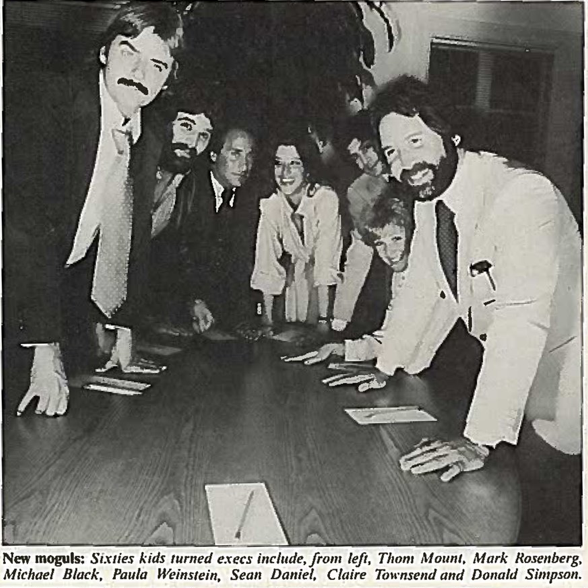

The opening-night party at the Los Angeles film festival was well attended by the Old Guard, epitomized by Universal’s 65-year-old Lew Wasserman, and the Current Guard, such as Twentieth Century-Fox’s 40-year-old Alan Ladd Jr. But the rock ‘n’ roll generation was out in full force. There was Donald Simpson, 32, the new vice-president in charge of production at Paramount. And Paula Weinstein, also 32, the new vice-president, production, at Fox. And Mark Rosenberg, 30, who has Weinstein’s old job, vice-president of production at Warner’s. Weinstein is the only woman that Hollywood is even willing to bet on to run a studio someday. She is Jane Fonda’s former agent and, before that, an SDS rebel at Columbia University during the 1968 protests. Rosenberg is an old friend of hers from those New Left days. He accumulated a 70-page FBI file as a student radical.

The “baby moguls” include a mix of studio executives, directors, producers and agents. Virtually all of these new movers and shakers are informal in their dealings with each other and are supportive and respectful of each other’s skills. Their interactions are marked not by the differences in their status, but by the common links of age and sensibility.

Among the young directors boogeying on the disco dance floor was Close Encounters’ Steven Spielberg, who, at 31, is an established superstar, and has already developed a protégé, 27-year-old Robert Zemeckis, who directed I Wanna Hold Your Hand. Also present were 25-year-old Amy Heckerling, a recent graduate of New York University’s film school, who has development deals to write and direct two films, and 27-year-old John Landis, who scored big with Kentucky Fried Movie and is now finishing National Lampoon’s Animal House starring John Belushi. “The last time I was in this building,” said Landis, “was at an antiwar demonstration to protest a visit of LBJ. I got gassed and stomped on.” And now that he’d made a hit movie, was he going Hollywood? “The major change in my lifestyle so far,” he said, “is that I take my wash to a laundry. I get my towels done at Fluff ‘n’ Fold.”

I had come to the party with the kid in the blue jeans and SDS button, Thom Mount. The newly named executive vice-president in charge of production at Universal, 29-year-old Mount will be responsible for making 25 films at the studio in the next year. It was through Mount, a former SoHo artist and correspondent for the radical Liberation News Service, that I had first become aware of the latest generation of the new Hollywood. He had been talking one day about several of his counterparts at other studios. He said they’d all been active in the New Left. He also talked about an even younger executive, 26-year-old Claire Townsend. The daughter of Robert Townsend, who wrote the irreverent book about American business, Up the Organization, Claire is the new vice-president for creative affairs at Fox. “I first spotted her,” said Mount, “on The Mike Douglas Show when she was head of the Ralph Nader task force on treatment of the elderly.”

At the film-festival party, we sat at a table that featured a generation gap. At one end was 30-year-old Michael Black, who refers to Sue Mengers as “my Mr. Chips,” and is considered the hot young agent most likely to inherit Mengers’s power and position. At the other end was 37-year-old Tony Bill, who was co-producer of the Academy Award-winning The Sting and was considered a leader of the last new Hollywood four years ago.

At one point, Mount turned to actor Martin Mull and asked if Mull would like to play an editor named Yawn in a movie based on the life of Gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson, and play him in a black fright wig. Mull laughed. Suddenly a reporter from Women’s Wear Daily intervened. Who, she wanted to know, did Mount think would inherit David Begelman’s job as head of Columbia Studios. Mount said he had no idea. She persisted.

“I really haven’t thought about it,” Mount said.

“Don’t lie to me,” she laughed.

“Look,” Mount said evenly, “you don’t get it. I haven’t the slightest interest in David Begelman or who takes his place. What people like him do or how they conduct their business has nothing to do with me or what I do.”

The baby moguls operate differently. It would be out of character, for example, for the new breed to argue—as it’s alleged producer Ray Stark and Paramount chief Barry Diller recently did—about who gets to call Rona Barrett with the announcement that Steve McQueen agreed to do a new movie. Unlike the Old Guard, the young elite gives low priority to glamour. “Bob Evans is the classic example of everything that does not interest me,” says director John Landis. A young studio executive says, “I wouldn’t be caught dead at one of Sue Mengers’s parties. Now she has to deal with a bunch of rock ‘n’ rolls kids who think she’s a big pain in the ass.”

The new generation wouldn’t read past the title of Gladyce Bengleman’s book, New York on $500 a Day. The kids are dedicated workaholics—almost all of then with some New York background or work experience—and their energy level is laid forward, not back. They drink Perrier and some do cocaine on social occasions, but mostly they do business—reading scripts, spotting talent, keeping up with everybody else’s deals, thinking of artistic packages, nursing creative people’s neuroses. “From Monday through Friday,” says Donald Simpson of Paramount, “no alcohol touches these lips. Then one night a week I give myself a good time—I go out to dinner with somebody I do business with.” The work breeds a terrible isolation. Agent Michael Black calls people outside the movie business “civilians.” Black is so singlemindedly involved with work that while he once attended SDS meetings in college and sheltered war protesters in his Washington apartment, he now says, “If I ever talk about politics, it’s to see if there’s a screenplay in it.”

The new guard calls the Polo Lounge the Polio Lounge. Its “in” spot is the funky Mexican restaurant, Lucy’s El Adobe, a horror of déclassé chic to those members of the Old Guard who think slumming is ordering a bowl of chili at Chasen’s. Baby moguls snort “kosher Chinese” at Roy’s restaurant on Sunset Strip, where the Bogart Booth is names not for Humphrey, but for Neil, the disco tycoon of Casablanca Records and Filmworks, Inc. They regularly confide to each other not the locations of posh new private clubs, but, rather, “I know a great little sushi bar.”

“None of us cooks. I barely know anyone who owns a dining room table,” says Weinstein. Rosenberg says, “I’m not into possessions much. I live in an apartment with some records and books.”

Bob Evans, for one, defends the old style. “The biggest deals at Paramount were made at my house,” says Evans. “It worked well for me. My home became a mecca for creative people. Because of my house, the company made $100 million. We’re in the business of style. If people forget style, we’re not giving the people out in the world what they want.” Evans is not impressed with the new generation. “I’ve heard some of these people are bright,” he says, “but none of these boy wonders knows how to make a picture. I don’t have a private screening room for pleasure. I do my homework. These kids don’t see one fifth the movies I see. I see eight, ten, twelve movies a week. I’m not just better prepared than they, I’m a lot better prepared.”

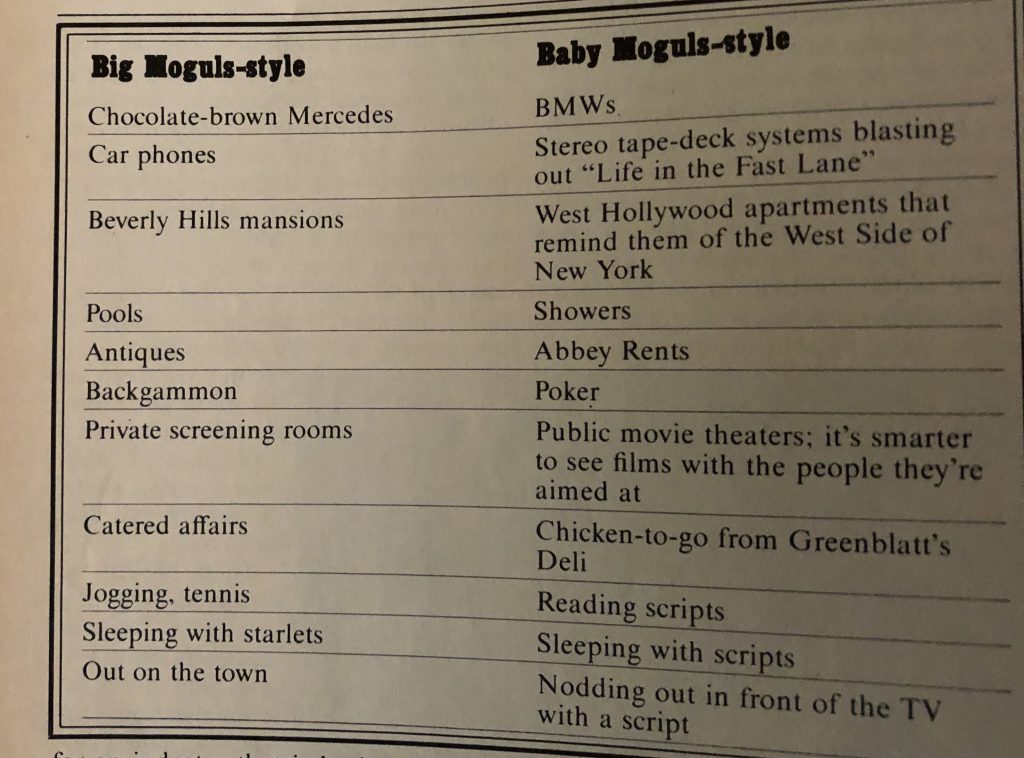

Like the generations before them, the baby moguls do live off a peculiar form of Hollywood welfare, though not to the same extent. The studio owns the cars they drive, sometimes pays part of their rents, picks up meal tabs and allows magazines, records, books—anything that can be loosely qualified as research—to be charged to the expense account.

Mostly bred in the East, the baby moguls have had some troubles adjusting to the mellow life. A 1974 Princeton graduate, Claire Townsend arrived in Los Angeles in 1975 to read scripts for producer Martin Ransohoff. After a few months, she felt so “weirded out by the city,” she called into a radio talk-show. “How do you meet people here?” she asked. “There are no sidewalks and I’m not going to cruise singles bars.” The deejay told her to show up at a miniature-golf tournament in Orange County. She did and suddenly found herself the winner of a contest. She was named “Miss Miniature Golf Tease.”

“About then,” says Townsend, “I changed the license plates on my old BMW to ‘Bell Jar.’ The spelled it, ‘Bel Jar.’ I still have them.”

It is not surprising that people in the new boy/girl network have come to rely on each other. Sometimes, they date each other and often, when they sense trouble—trouble is defined as “pictures and deals going down the tubes”—they call each other, both to lend support and to be critical. They often talk about a camaraderie in which generational ties transcend job loyalties. “I am concerned and care about a lot of people who are in fact my competition,” says Donald Simpson. “I am convinced people don’t talk to each other the way Thom Mount and I do in the business or when we meet socially because of our shared background of the sixties. We’re just straighter. In general I don’t think there’s any substantial difference in the way business is conducted, but there’s a little less shucking and jiving. It’s not about righteousness. It’s about wanting to be cleaner and more direct.”

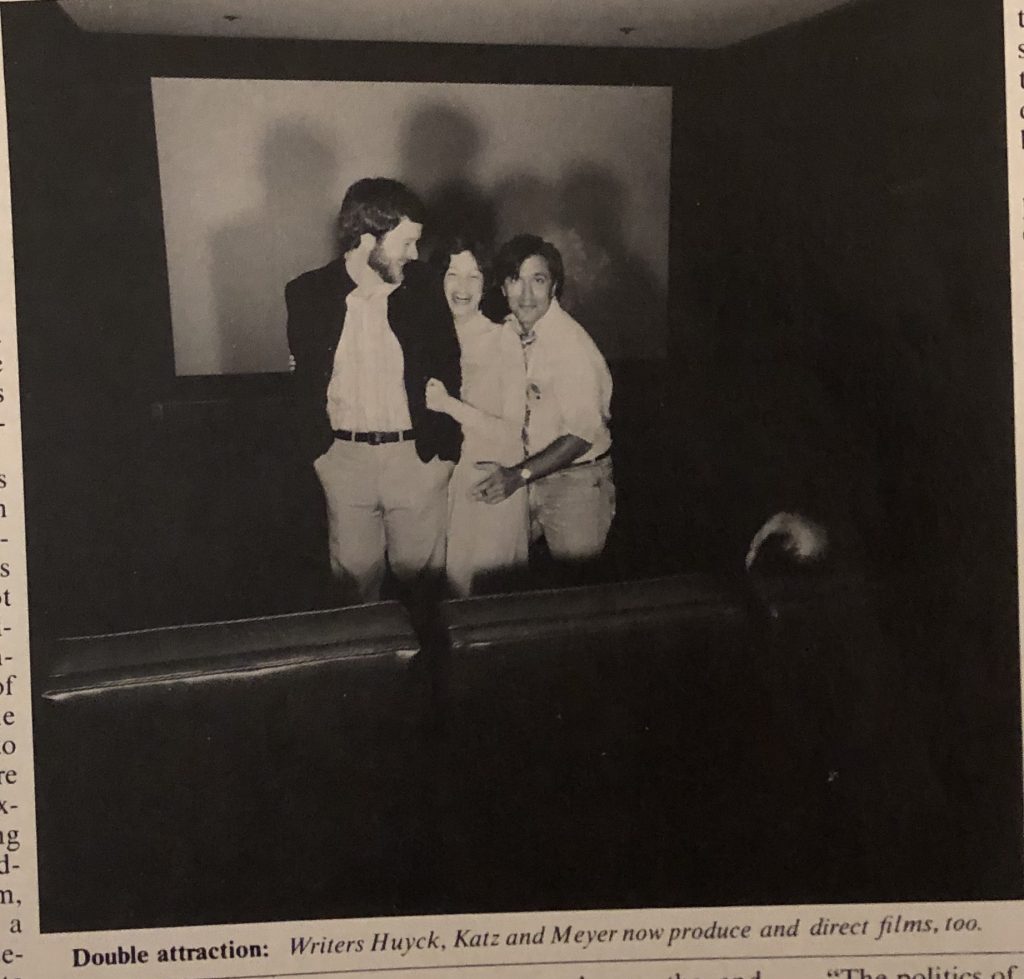

The rise of the baby moguls has materialized from a number of circumstances that have made this the most favorable period in years for change in the movie business. First, creative people have never been more powerful. With such diverse films as Saturday Night Fever, Annie Hall, Oh, God!, and Smokey and the Bandit becoming major hits, the studios can no longer rely on imitative formulas as the safest way to make money. While stars are still important, the script is becoming the most important element in any film. Hollywood is wide open for new stories and ideas, open for young, creative people, and open for a generation of executives fresh and flexible enough to find this creative talent and nurture it in innovative ways. Increasingly, scriptwriting is becoming the easiest route to a director’s job. In the last two months alone, four young screenwriters signed to direct new scripts they’ve written—something Hollywood veterans cannot remember happening before. As part of the price for their widely solicited original scripts Nicholas Meyer, who wrote The Seven-Percent Solution; Matthew Robbins, who co-wrote MacArthur; John Byrum, who wrote Harry and Walter Go to New York; and Willard Huyck, who co-wrote American Graffiti, will all be allowed to direct the movies made from their scripts. Huyck’s wife, Gloria Katz, who co-wrote his new script, will be producer of the movie.

Second, studios are realizing that 74 percent of the filmgoing audience is between the ages of 12 and 29, roughly the same age group that buys most of the records. The studios need filmmakers and executives bred on pop music, people who understand the sensibilities of this audience. Moreover, it is now understood that the movie itself is merely the starting point for virtually limitless exploitation of a property, including soundtrack LPs, books and a half dozen different kinds of TV rights, including those for video discs. The studios need chiefs who understand the importance of negotiating a hot soundtrack album, chiefs who are familiar with the uses of videotape. Millions of dollars have been made from the soundtrack album of Saturday Night Fever (13 million records sold so far); the myriad Star Wars products have created a heightened awareness that creative control today goes far beyond the final cut of a picture. The studios are seeking out people with backgrounds more sensitive to the creative psyche than those who basic credentials are ten years with the William Morris agency, starting in the mailroom.

The rock ‘n’ roll generation is also supplying the studios with executives who are comfortable in providing freedom of expression and opportunity for two increasingly important pools of talent—women and gays. “I told our highest ranking gay—a man in his forties—that he wasn’t out of the closet enough” says one young executive. “I told him to be more blatant because we were missing connections that could bring us interesting deals.”

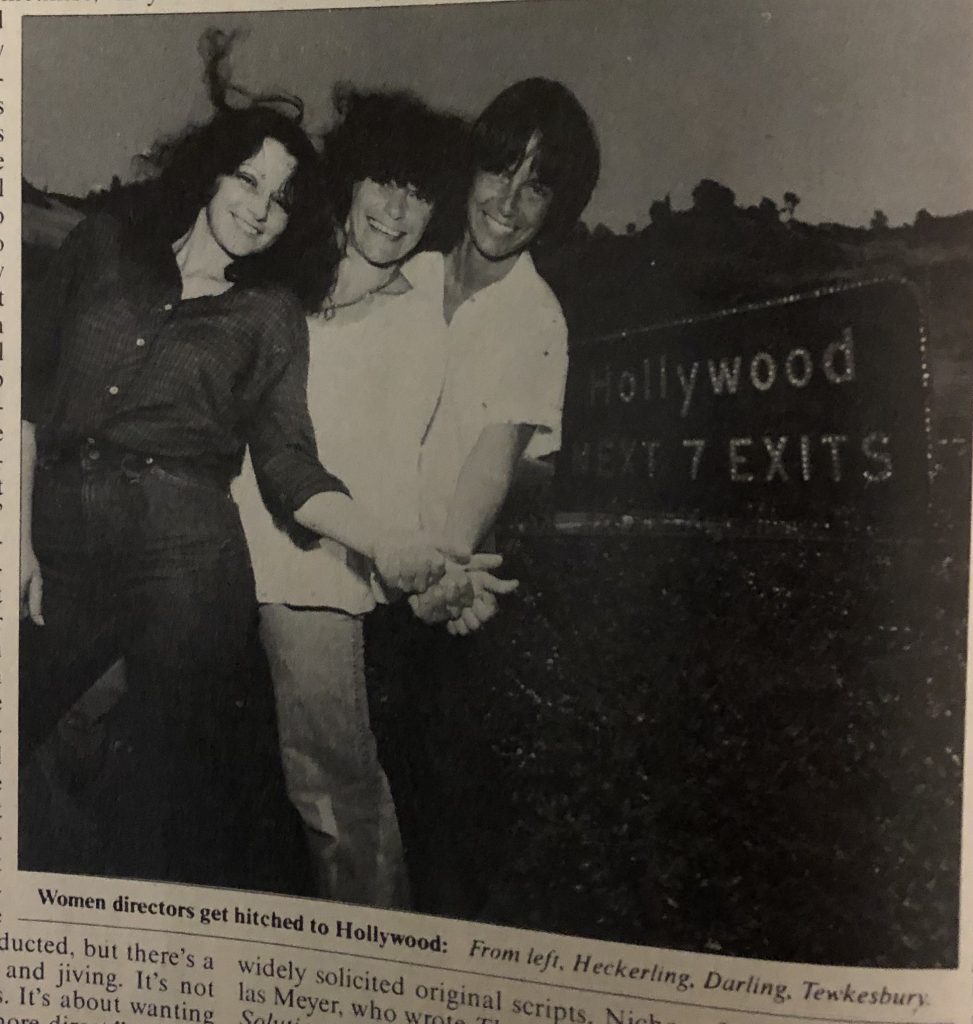

Three years ago, the only woman director working in Hollywood was Elaine May. Currently, at least seven women directors, including Joan Darling and Joan Tewkesbury, are shooting Hollywood films or are involved in development deals with major studios. There are also a handful of women producers, about a dozen prominent women agents and at least one female vice-president at each major studio except United Artists and MGM. But only two or three of these female film executives have risen about the token level. Women are mostly treated as glorified script readers. They are still rarely allowed to cut deals, and there is only one woman in a position of even secondary importance on the business-affairs staff of any major studio.

But everyone seems to agree that the more power the baby moguls accumulate, the more progress will be made by women. Already there are beneficiaries. “It’s a good time to be a woman in Hollywood,” says 25-year-old director Amy Heckerling. “I expected to meet fat old producers with cigars in their mouths at the studios. Instead I met these gorgeous young guys and really supportive women executives. Nobody’s tried to shove anything at me—they have all been very protective.”

What most distinguishes Hollywood’s new-breed generation from its predecessors is its background—not only more political, but generally more sophisticated. The lives of three top baby moguls offer good illustration:

Paula Weinstein’s mother, Hannah Weinstein, is a producer who was named, though not blacklisted, in Hollywood’s anti-Communist purges of the fifties. The family moved to London, where Paula was exposed to strong female role models—among them, Lillian Hellman, a frequent houseguest. Paula came to the U.S. to attend Columbia University, where her political activism eventually led her to people who gave her a start in the movie business.

Thom Mount, the son of a prominent liberal attorney in North Carolina, was a leader of antiwar demonstrations throughout the South. After graduating from Bard College, he gave up a promising career as an artist to pursue film because he found painting “too isolating.” He got a master’s degree in film from California Institute of the Arts and started his Hollywood career by reading scripts for producer Danny Selznik. In 1975 he went to work as a $300-a-week assistant to the head of theatrical motion pictures at Universal Studios, Ned Tanen. Today, he is number two at the studio.

Donald Simpson, a third-generation Alaskan and son of a bush-pilot wilderness guide, is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Oregon. Simpson started out in Hollywood doing market research for films, then wrote scripts. In 1975 he became assistant to an executive at Paramount, where he is now the vice-president in charge of production. Like the others, Simpson views the power of film with an awe that is almost embarrassing. When he was ten he became so distraught after seeing The Greatest Show on Earth—“because Jimmy Stewart, the clown, turned out to be a murderer”—that he refused to go to school for two days. “I told my mother to tell the theater owner to change the ending,” says Simpson, “and from that point on, I knew I wanted to involve myself with that magical form.” With the same reverence, 34-year-old David Field of United Artists says, “I’m fascinated with movies. I think movies are the most incredible art form in the history of the world—they’re like dreams.”

The presence of the former radicals in Hollywood raises a basic question: Aren’t they, to recoin a phrase, “copping out?” Paula Weinstein admits she feels conflict. But her politics, she says, is what launched her in Hollywood. “I came out here and knew absolutely nobody, but Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland supported me and let me become their agent because they were interested in someone who shared their beliefs. They told me they wanted someone who saw films and life the way they did.”

Thom Mount expresses the opinion of most of the others when he maintains that his main rationalization for wheeling and dealing inside the establishment is the hope that he is helping to establish a new set of ethics. “These days I see male scriptwriters struggling in their scripts to avoid female stereotypes and write strong woman characters,” Mount says. “I myself am very conscious of our responsibility with regard to on-screen violence. I don’t want to make films which harm the social fabric.

For Warner’s Mark Rosenberg, the move to Hollywood was part of the process of growing up and beginning a career, a natural transition for someone nurtured on the show-biz-conscious tactics of the New Left. He says, “A lot of people involved in the sixties had to say, ‘I’ve gone through an extremely traumatic period of my life; now I’m going to figure out the rest of my life.’ Today, many of us still feel at the center of things because Hollywood is under a microscope. But the sixties gave us a feeling we were in the midst of an historical reality, and sometimes I feel there’s not a shred of reality to this business.”

“The politics of the future is the politics of media,” Mount says. “The sixties are relevant to me in the kinds of business ethics one exercises and in the choice of films to make. Yes, I’m in conflict about working inside a corporate structure, but what we learned in the sixties is that trying to build an alternative structure outside the system—given the power of the system—is never going to work.”

A cynical observer of both the political and entertainment scenes recently said, “I often wondered where all the student radicals would go when they grew up. Now I know. They came to a place where they never have to grow up.” It is an ironic fact that participation in New Left politics was excellent training for an industry that is basically a crap shoot. “You had to organize people around ideas and decide whether to take positions or not,” says Weinstein. “You had to go to the police and the press. That whole period taught me not to be frightened. It was great training. After a bayonet’s stared you up your nose, what’s to be scared of taking risks?”

What sort of risks will the kids take, now that they’re beginning to accumulate what Hollywood calls “yes power”? “To this point,” says one producer, “the younger guys had a cop-out. They could say, ‘I love it but I can’t get it through.’ It’ll be interesting to see what happens when they can’t give that excuse.”

The first signs of what they’ll do are here. At Paramount, Donald Simpson has just bought Dress Gray, in which a homosexual murder at West Point serves as a metaphor for the collapse of the system and values West Point stood for. Simpson is also supervising the gangster comedy, Dick Tracy, and American Me, the murder of a Chicano gang leader who tries to convert the gang from heroin pushers into a political force.

Twenty-six-year-old Sean Daniel is supervising Loretta Lynn’s life story, Coal Miner’s Daughter, at Universal, and the National Lampoon’s Animal House comedy. At the same studio, Mount has already madeSmokey and the Bandit, which has so far returned $50 million, and Blue Collar, which has brought in no profits. He is now making the movie about Hunter Thompson, a film on country singer Willie Nelson, plus a western based on Nelson’s LP, Red Headed Stranger, and a movie about Melvin Dummar.

At Fox, Paula Weinstein is in charge of Stormy City Bowl, which sounds like Saturday Night Fever in a bowling alley, and Accomplices to the Crime, the true story of a reform prison warden defending prisoners against exploitation. “Everybody’s got at least one or two socially conscious films,” says Mount. “If they try two a year, they’ll probably get one made. That’s about six a year with content. I don’t think you’d find that many in recent years.”

The new generation has few illusions about the industry. “One of the major problems here,” says one young executive, “is that the people who run studios have absolutely no social responsibility.” And so far, three projects championed by the new executives—the politically radical working-class drama, Blue Collar, the rock saga, American Hot Wax, and the Beatlemania spoof, I Wanna Hold Your Hand—have all done poorly at the box office. Because it’s the bottom line that still matters, much of Hollywood is deeply cynical about what effect, if any, the baby moguls will ultimately have. “The minute these guys read their press releases in the trades announcing their titles, the blood drains from their heads,” says producer Art Linson. “They begin to play it safe. If they go down the chute, you can be sure they want to take Robert Redford with them. Listen, the guys in charge set these people up. The studio head figures that if he gives the young guys titles big enough, then the kids can absorb the bullshit—go down with the losers and take the calls from the agents they don’t want to talk to but can’t afford to piss off.”

Nevertheless, at United Artists, David Field passes up certain movies that might be profitable “because if you begin a project and don’t believe in it except that it’ll make money, I don’t want to get involved; it’s wrong.” And Michael Phillips, coproducer on The Sting, Taxi Driver and Close Encounters, says, “I can’t tell you how happy I am to see these new people. It’s the best thing that’s happened to the business in years. When I deal with them I feel they’re more direct. They say, ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it.’ I don’t hear, ‘I think it’s commercial’ or ‘It’s not commercial.’ They aren’t making decisions based on the success of what’s come before. They’re more sure of their taste. It will be interesting to see how they succeed.”

Naturally, they face large hurdles and dangerous traps; witness the creative excess and self-destructiveness of the last new Hollywood: Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now us a year overdue and past the $30-million budget mark, Martin Scorsese’s self-indulgent New York, New York, was an $8 million bust, and a powerful young producer’s reputation was ruined by the six-figure cocaine budget on a blockbuster movie. But this newest breed, as it jockeys for position, most often compares itself to the generation that ran the Hollywood of the thirties, when the diversity of films was great and camaraderie was strong. Perhaps that view is overly romantic. But the rock ‘n’ roll generation has already had an impact on American culture. It doesn’t seem ridiculous to think these people can make some changes in the way business is conducted in Hollywood.

At the very least, the baby moguls bring a new self-awareness to the old seats of power. “The sixties will have come to nothing,” says Weinstein, “if we have come through them and don’t know how to apply those cultural experiences—if we become so involved in power and the accouterments of power, the big bucks and fast money, that we forget the passions we’ve learned. We’ve got to keep them—it’s the only way to make films the people out of the fifties couldn’t make.” Weinstein pauses. “The jury’s out,” she says. “We’re new arrivals. We’re still proving ourselves. The process is just as competitive as it always was. But the difference,” says Paula Weinstein, “is that we’re willing to talk about it and question it.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.