Original Publication: Vogue – July, 1980.

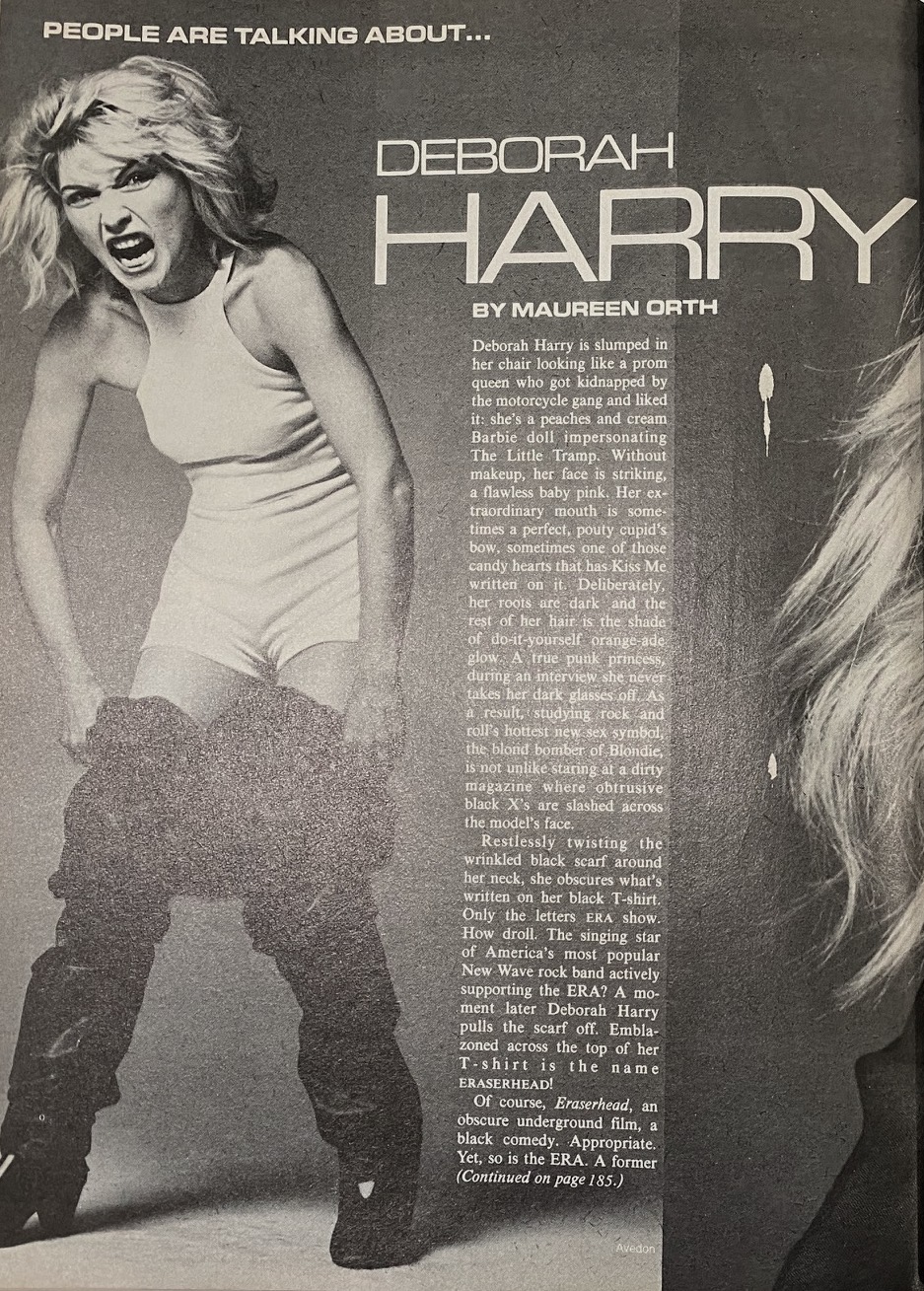

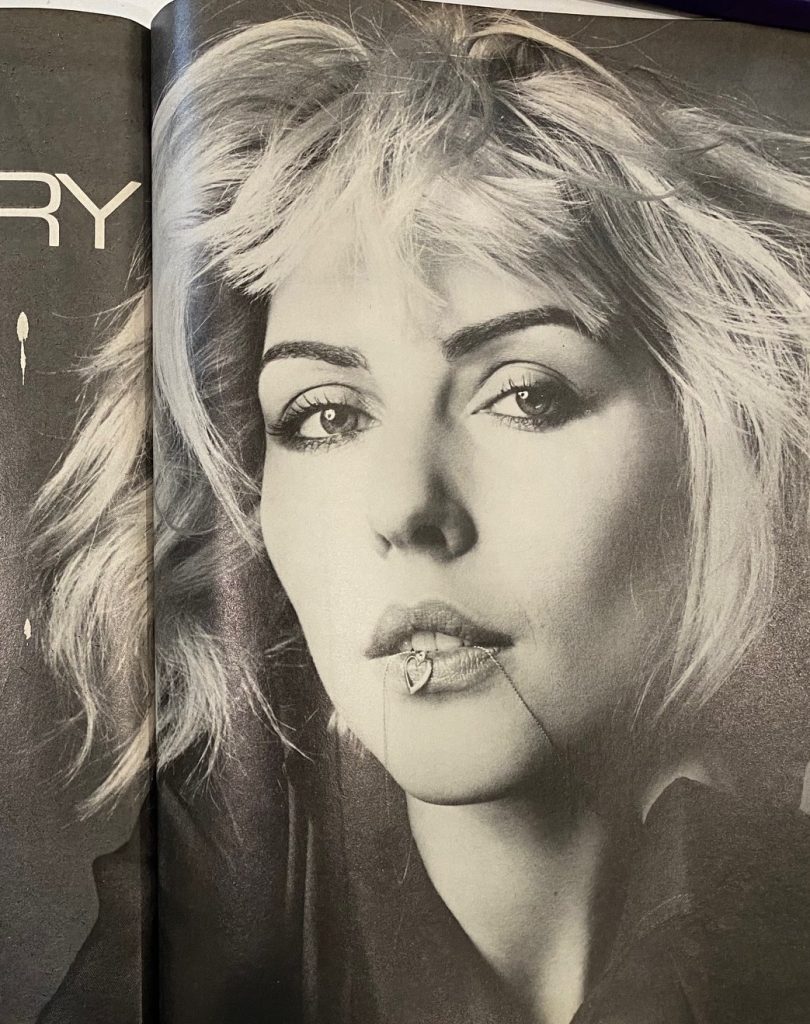

Deborah Harry is slumped in her chair looking like a prom queen who got kidnapped by the motorcycle gang and liked it; she’s a peaches and cream Barbie doll impersonating The Little Tramp. Without makeup, her face is striking, a flawless baby pink. Her extraordinary mouth is sometimes a perfect, pouty cupid’s bow, sometimes one of those candy hearts that has Kiss Me written on it. Deliberately, her roots are dark and the rest of her hair is the shade of do-it-yourself orange-ade glow. A true punk princess, during an interview she never takes her dark glasses off. As a result, studying rock and roll’s hottest new sex symbol, the blond bomber of Blondie, is not unlike staring at a dirty magazine where obtrusive black X’s are slashed across the model’s face.

Restlessly twisting the wrinkled black scarf around her neck, she obscures what’s written on her black T-shirt. Only the letters ERA show. How droll. The singing star of American’s most popular New Wave rock band actively supporting the ERA? A moment later Deborah Harry pulls the scarf off. Emblazoned across the top of her T-Shirt is the name ERASERHEAD!

Of course, Eraserhead, an obscure underground film, a black comedy. Appropriate. Yet, so is the ERA. A former art student, a former junkie, a former Playboy bunny, a former former, Deborah Harry is most of all an electric performer and ace songwriter, someone who has often taken personal and professional risks. “You have to be brave if you’re going to become a total person,” she says simply. But don’t be fooled. At thirty-four, Deborah Harry, tough, talented, and terrific, has burst on the scene as new wave’s biggest star; and, like Bette Midler in her early days, she is destined to go beyond the celebrity of pop music.

Deborah Harry is lead singer and leading attraction of Blondie, the first band to emerge from the punk scene and rock’s anti-commercial underground axis to become a major commercial success. In just two years, Blondie has sold nearly five million albums worldwide and, in the last year, has had two number-one hit songs: “Heart of Glass” and “Call Me,” the theme song from American Gigolo. This summer, Deborah Harry and Blondie will be making their feature film debut in Roadie, and in true ‘eighties celebrity fashion, she will be endorsing a line of designer jeans on nationwide TV.

New Wave, which combines the energy of punk with the melody of pop, is more than the dominant new force in pop music today. It’s also a style, a way of looking and behaving. In an era of limits, the days of indulged rock bands who tour in private jets with an entourage of hundreds are on the wane. New Wave, cynical, direct, often ironic, is still played mostly in clubs as opposed to giant concert halls. These clubs, which mix old-time rock tunes with the work of bands like “Four Out of Five Doctors” and “The Consenting Adults,” are rapidly replacing discos around the country as places to be on Saturday nights. The whole ‘fifties mod look of skinny ties, oversized jackets, and baggy pants was first seen on members of punk/New Wave bands and their artistic friends. Their inspiration was Buddy Holly and the early roots of rock and roll, from which this music is recycled – in reaction to the soft rock of the ‘seventies’ singer-songwriters and the predictable formula of disco.

“In the ‘sixties, great, wild Jimi Hendrix was blaring on the radio,” said Deborah Harry. “Then the music became like John Denver’s ‘Rocky Mountain High.’ Give us a break. We want to breathe; we want to dance; we want to jump around . . . When we started Blondie in ’73, our main goal was to be a dance band. The idea of performing rock and roll to a stand-up audience that danced was unheard of. We’ve gotten through to club owners on this only in the last year.”

If the ‘sixties were idealistic, Woodstock and sylvan, Deborah Harry is knowing, New York, and urban. Women superstars in rock are rare enough to begin with: Most, like Janis Joplin, made their reputations by being earthy, vulnerable, and singing the blues or, like Linda Ronstadt, as ingenues wailing mournful country tunes. Debbie Harry tells men to get lost. In a dreamy distant voice, of course, one that doesn’t threaten. She’s both a harbinger and a throwback. Her looks recall exaggerated sex symbols like Jayne Mansfield and icons like Marilyn Monroe; thought, physically, she’s more petite. True to the style of music she sings, however, Deborah Harry has recycled herself as a blond sex object by undercutting her sexuality with wit and ironic distance.

“I’ve always thought of sex as very, very important,” says Harry. “But I don’t think of Blondie, or myself as Blondie, as overtly sexual. What I wanted was for girls, especially, to be more lighthearted about sex, love affairs – not like having it be the end of the world if it didn’t work out.”

She tells audiences that, “of course, cool rhymes with fool” and mocks the cult of youth with her song, “Die Young Stay Pretty.” “It’s like a slap in the face, that statement,” says Harry. Absurdism and nihilism have replaced lost innocence. The generation she sings to doesn’t expect peace and love. You can tell from her lyrics:

When I met you in the restaurant

You could tell I was no debutante

Or

Don’t go away sad,

Don’t go away mad, just go away.

Onstage and on camera, Deborah Harry is a dynamic sexual presence; she’s got it and she flaunts it with her own brand of sexy throwaway tongue in chic. It’s her secret weapon, why she appeals to men and women, old and young. She’s also a wonderful combination of street smarts and naïveté; who cultivates the outrageous but never without a sense of humor. She may be the Carole Lombard of the ‘eighties.

“I’m a big pain freak,” she confided by means of explain her ability to jump into diverse experiences. When asked what she did for pain these days, she said, “I put on lots of makeup and a mini skirt and walk down [New York’s] Fifty-seventh Street.”

Deborah Harry grew up in Hawthorne, New Jersey, the adopted daughter of conservative Episcopalian parents who ran a gift shop. Even as a little girl at the circus, she analyzed performances. “I always watched the rigging and stagehands, the lighting, and wondered whether the band was bored.”

In high school, she was a majorette and voted the prettiest girl in the senior class, but she was quiet, hardly a show-off. After trying college briefly, she drifted to the East Village in the late ‘sixties. It was the height of hippiedom; and, during the next decade, Debbie was party to every fad and trend from fold-rock to hard drugs, getting herself hooked on heroin, but was able to overcome her addiction. She sang in a folk-rock band, continued to study art, but dropped it for music when she began painting pictures of sound waves and realized she wanted to be a singer. Her present style evolved from New York’s early ‘seventies underground art scene where she hung out in the back room of Max’s Kansas City, a place where costume was a statement, another form of art.

In 1973, Deborah Harry began wearing mini skirts and fishnet stockings. It was deliberately kitsch-y, one of the first looks after glitter and an alternative to early punk. She formed a flashy, trashy, all-girl band, The Stilettoes. That same year, her life changed when, just as in the song, she met a very bright young art student who played the guitar, Chris Stein – in a restaurant. He was brash, idealistic, interest in film and politics. Together, they formed Blondie and have been inseparable ever since.

“I myself feel like I’m married,” says Harry. “I’m one of the very very lucky ones. Being with Chris for seven years plus working together – it’s really strange. I never expected anything like this to happen.”

Yet, she also feesl comfortable with a more traditional role for women. “There’s nothing wrong with being a wife – any one of us could be happy doing it. I just happened to make a decision years ago that I would take my chances and try to do something. It just seems so pathetic that a lot of women degrade [or “denigrate”] themselves because they’re married and don’t have a career. It’s a real tragedy because I think that a good marriage is the greatest thing in the world.”

Harry, the most prolific lyricist of Blondie, writes on snatches of paper themes, or lists of subjects she wants to cover. Then she composes to the music with one of the musicians. One of Blondie’s biggest hits was “Dreaming,” written with Chris Stein.

“Chris is a kind of philanthropist,” says Debbie. “His whole thing is that he wants to give something to people and dreaming is free. So if you encourage people to have a dream life or a fantasy then it’s a really nice present.”

In the world of the rebellious and irreverent New Wave, however, there are those who resent Blondie’s success, who feel Debbie and Chris and the rest of the band have sold out. Harry herself admits, “Our earlier shows were much funnier and campier. We’ve gone into a real slick commercial interpretation of what we were.” Today, after years of struggle and music-business chicanery, Blondie no longer plays local dives but tours as a major attraction The pressure takes its toll. “I feel just like an athlete in training when I’m on the road,” says Harry.

Beyond their music Deborah Harry and Chris Stein are intensely interested in film. They are at work on a treatment for a screenplay. He’d like to direct; she wants to act.

Deborah Harry is her most dynamic in front of a camera. She has one of those faces that can transform itself endlessly, hypnotically. The camera fixes on her high taut cheekbones and pouts her mouth even more. Does she herself feel the magic? “You can’t be self-conscious but it’s totally Self-Conscious,” says Harry. “It’s like getting out and being the camera yourself. It’s the same thing with a performance. The energy goes out and it comes back. It’s like soup.” Soup! Soup? Deborah Harry nods gravely and suddenly she has the beguiling expression of the little blond angel on top of the Christmas tree. Warm, comforting – like soup.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.