Original Publication – Newsweek: October 28, 1974

Verna Fields is not a glittering name on a movie marquee. She’s neither a hot young director nor a big-time producer. But at a time when women are fighting to achieve at least a modicum of power in the production of films, she is one of the most influential women on the Hollywood scene. In the last two years, film-editor Fields has cut “Paper Moon” and “Daisy Miller” for Peter Bogdanovich, “American Graffiti” for George Lucas and assisted on “The Sugarland Express” for Steven Spielberg with whom she’s now working on “Jaws.” Her sense of what makes a good story, her instict for how a film should flow and her dedication to enhancing the director’s vision have made her Ms. Indispensable on whatever movie set she works. For a skillful editor can often make all the difference between a movie that doesn’t work and one that does.

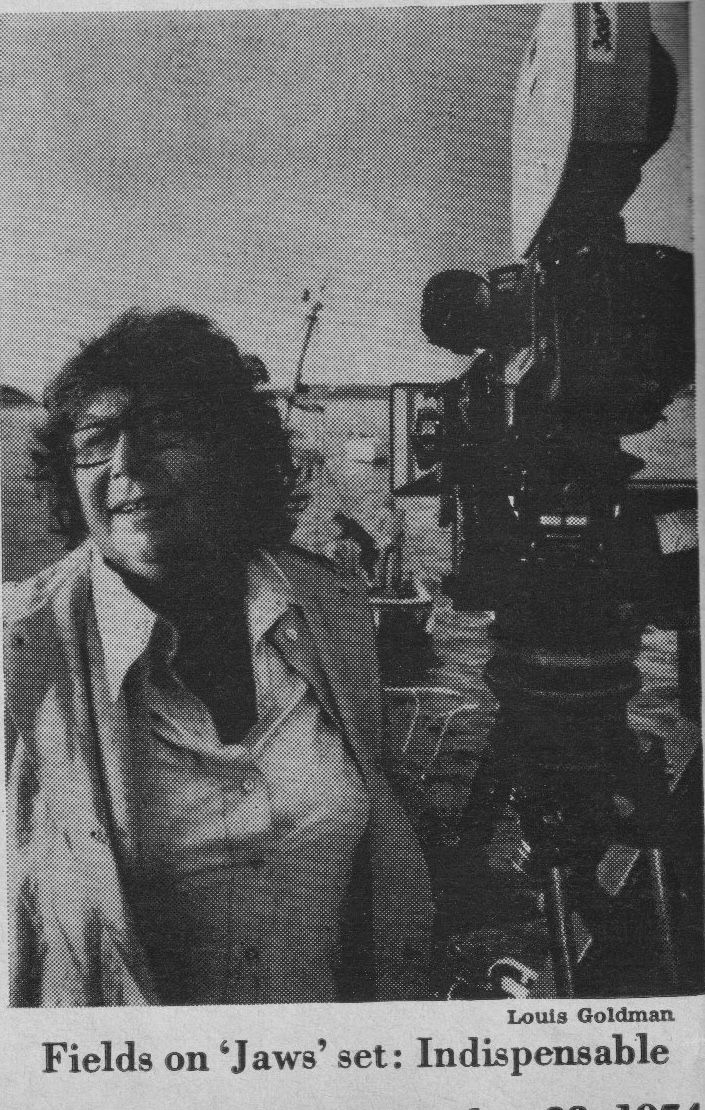

Unlike most editors who wait until a film is shot before they begin to work on it, Fields goes on locaiton with her directors. “I have to get inside their heads,” she explains. “I’m more supportive than most editors. The directors can bounce ideas off me and see if they work intellectually and emotionally.” Recently, on Martha’s Vineyard, at the end of five harrowing months of shooting “Jaws” – the movie version of Peter Benchley’s best-selling novel about a man-eating shark that terrorizes a resort community – Fields was everywhere. She huddled in meetings on speedboats with executive producer Richard Zanuck. She interpreted Spielberg to Zanuck and Zanuck to Spielberg when they were both busy doing other things and conferred with the director as he set the final shots.

Terrified: “This is one of the most technically difficult films ever attempted,” she told NEWSWEEK’S Maureen Orth. “We used a mechanical shark for some shots, and if the audience is not terrified of that shark, if it makes anyone in the audience laugh, you’ve had it.” When not on the set, Fields was back in her hotel cutting the first two-thirds of the picture. “I can give Verna three adjectives to express my meaning about how a scene should feel,” says Spielberg, “and she’ll put it into a rough-cut assembly and suddenly it’s four adjectives – my three plus hers.”

Fields, who is 56 (“but I feel 24”), spent part of her youth in Europe and part in Los Angeles where her father, a writer, was under contract to M-G-M. During World War II, a friend who was working as an assistant editor on a Fritz Lang movie invited her to help out. “I don’t know whether I fell in love with editing or the guy in the editing room,” she confesses. But she did marry they guy, Sam Fields, and learned her craft at the same time. “One reason a few women have been able to maintain a place in editing,” she says, “is that men don’t feel competitive with women editors. Usually bright young male editors want to be directors.”

Vengeance: In 1954, Sam Fields suddenly died of a heart attack at 38, and Verna, with two sons under the age of 5, went back to work with a vengeance, coming home early to be with her sons and then returning to the studio to work far into the night. She edited “Death Valley Days” and “Sky King” for television, made her movie feature debut with “El Cid” and cut the sound tracks for Bogdanovich’s first film, “Targets.” She began teaching editing at the University of Southern California film school and quickly became Mother Cutter to a whole generation of film students. “Verna always let us come over and use her equipment for free,” says one of her protégés. “She used to get desperate calls at midnight from students saying, ‘Hey, Verna, you got a track of footsteps on gravel we can use?’”

In the late ‘60s, she formed her own film company and began producing and directing documentaries for the Office of Economic Opportunity. “The use of film as a tool of social change is one of my primary interests,” she says. “Cutting documentaries is a lot more challenging than working on a feature because you’re really writing it by the way it’s cut.” But when the Nixon Administration stripped OEO of most of its funding, she went back to features, editing “What’s Up, Doc?” for Bogdanovich. Fields believes that good editing should be almost invisible. “You must create emotion with the least awareness of technique,” she says. Her skills were challenged in the complicated chase scene in “What’s Up, Doc?” and in telling what amounted to four separate stories in “American Graffiti,” most of it in moving cars.

She meets other challenges, too. When Universal, incredibly, was reluctant to back “Graffiti” (the film has grossed $40 million to date), Fields prodded the studio bosses. They listened – and a grateful Lucas has just presented her with a brand-new BMW automobile as a reward. Recently, she received a letter from Bogdanovich saying that when he realized he was starting a new movie without her, he burst into tears.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments