Original Publication: New York Woman, May/June 1987

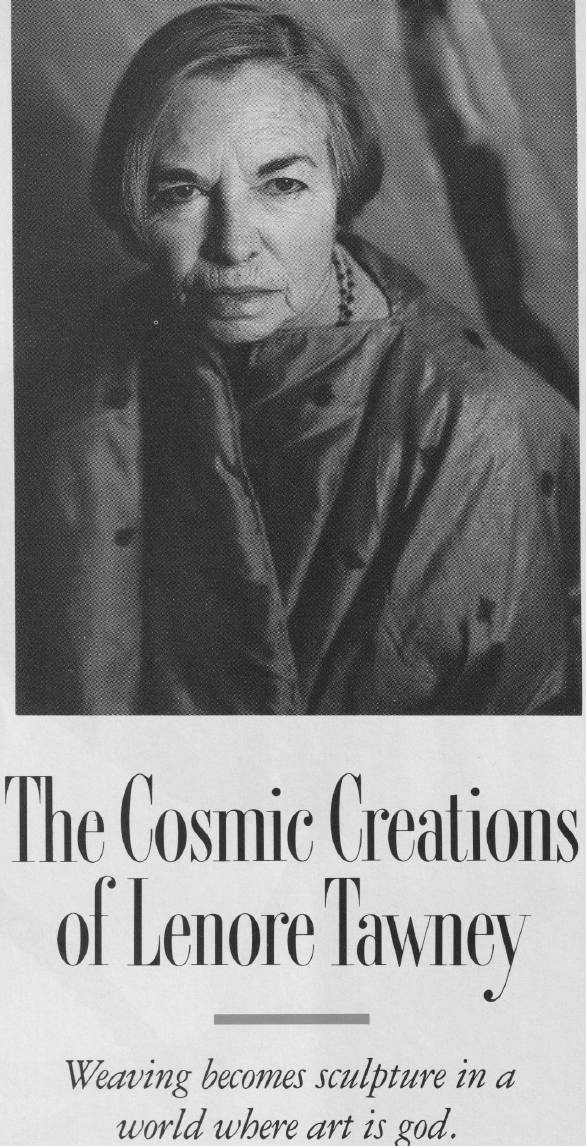

She is a tiny apparition dominated by a deep and powerful sensitivity. In both life and work she weaves a spell with small, strong hands and soaring vision. The magic is palpable the moment you step from the noise and grime of the Chelsea street below, remove your shoes, and enter the carefully composed quiet of Lenore Tawney’s loft. The artist herself inhabits what amounts to a 4,000-square-foot collage of her life. Amidst meditative stones, philosophical tomes, and bits of feathers and bones, Tawney cloaks herself in Syrian shepherds’ robes lined in sari silk– her hair sometimes hennaed bright red, sometimes toned down to burnt sienna. In the world of fiber art she is as important a creator as Louise Nevelson in sculpture, as Georgia O’Keeffe in painting. The American Craft Museum will sponsor a traveling thirty-year retrospective of her work in 1988 or ‘89. However, except for cognoscenti collectors like the Metropolitan, MOMA, or Isamu Noguchi, Lenore Tawney is almost totally unrecognized by the public at large.

For three decades Tawney has pioneered with loom and thread, transforming what was known as weaving into textile art. In 1961 her exhibition of wall hanging at the Staten Island Museum, followed by an appearance at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and a 1963 show at the American Craft Museum, launched a new age of tapestry in the U.S. Tawney was the first to incorporate open weave and to suggest drawings in the warp of the loom, the first since Indians to tie shells and feathers into her fringe, and probably the first to coin the term woven forms for her three-dimensional works — exquisitely and painstakingly disciplined monochromatic pieces that elevated mere weaving into sculpture.

In the seventies Tawney pioneered again with a series of “cloud formations” for public space — 13,000 separately strung and knotted linen threads cascading sixteen feet down from two-story ceilings like baths of shimmering rain. Lately she has hung chairs attached with feathered wings or nestled inside a giant silk embryo. The idea for the chair inside silk came to her in a dream. She woke immediately and began to work.

Says Katharine Kuh, the eminent critic of twentieth-century art and an early supporter of Tawney’s, “Lenore led so-called fiber art out of the range of anything like weaving and made her pieces full of her dreams and connections and filled them with allusions. Her two strongest influences are Indians, American and Asian. Her work is very much a mystical journey, and her weavings are hardly weavings; they are great transparent bas-reliefs.”

Tawney’s loft is filled with a mixture of the religious and primitive, the symbols of which inform all her work. Her female guru, Swami Gurumayi, smiles from above the kitchen stove. The late Swami Muktananda, beloved “Baba,” is above the sink. There are a series of Cornell-like chests of myriad drawers; inside each drawer is a tiny work of art, be it an assemblage of cracked birds’ eggs or a pale oriental bowl filled with water. Elsewhere, a child’s Mary Jane is covered with the pages of a rare book and filled with rose petals. Twenty-seven-foot woven hangings are casually rolled up against a wall.

Tawney considers her work a meditation, and the thousands of delicate knots she’s fashioned are her mantra, if not so many decades of the rosary. (One can practically trace the sixties’ macramé craze to these very knots, though she disdains the humble ties “that came after.”) Late at night when she’s not working, Tawney dips into the works of sixteenth-century mystics such as Jakob Boehme the way most of us peruse the Home section of the Times. Journals she keeps are jammed with the thoughts of Kierkegaard, and passages from her Good Book, an analysis of the Jungian archetype, The Great Mother, by Erich Neumann.

Neumann helps Tawney explain her art to herself with his primordial descriptions of weaving. The three Greek goddesses of Fate, for example, the Klothes, were weavers. In fact, weaving has always been a major way of tapping the Great Mother. Tawney can see a Renaissance painting of a Virgin with the child in her womb and explain. “When the mother is carrying the child, she is weaving the tissues of the baby.” Similarly, she cites the Greek word mitos, “which designates the male seed as woven thread.” And twenty years after weaving a huge form in black-and-white linen, Tawney has recently understood it “as a struggle to reconcile the male and female within myself.”

Resplendent recently in total eggshell white, and sitting cross-legged on the pickled white floor of her loft, Tawney, whose indeterminate age is a closely guarded secret, exclaims, “I am an all or nothing person.”

No kidding.

Tawney lives, as Kuh says, “on a little different plane with her work,” and there is not doubt that art called her just as surely as God called St. Theresa. At first, though, she resisted. As a young and attractive student of the master sculptor Archipenko at the Chicago Institute of Design, she felt both art’s all-consuming ecstasy and its overwhelming loneliness. “I realized that I couldn’t sculpt unless I could give myself to it completely. I felt I needed a personal life.” She chose men over vocation, married twice; and it wasn’t until her second husband died, only a year and a half after they were married, that she turned to weaving– at first as “something to do when I wasn’t having a good time doing anything else.”

Always a restless, deeply religious person, she struggled with a crisis of faith– specifically with the Catholicism of her upbringing in Lorain, Ohio: “Reading Schopenhauer one day I just vomited it out the window.” Cast adrift and left financially independent, she roamed to Africa and the Middle East, looking for spiritual roots. (“There was lots of the Great Mother in Egypt, Syria, and Turkey.”) She took solace in a passage from the Indian master Vivekananda; “All paths lead to God.”

In 1957, the path led to New York. Tawney rented one of the very first artists’ lofts, three floors of an old sailmaking factory on South Street, and began weaving with the devotion of a monk chanting scripture. “Working became a way to know God,” Tawney says now. “Everybody has that divine spark, and that spark in me connects with Her when I’m working.” Living in that loft (the first of eight Tawney has redone from scratch), she would gaze day after day at the river, especially at the giant knots tied on the sides of the passing tugboats. Almost unconsciously she began to invent a new form of weaving.

“When I was doing the woven forms, I was dancing with joy all the time. They were so spontaneous. I didn’t know what they were– they just kept going higher and higher. I thought, “No one will ever show these; they’re too tall for a gallery so I’ll keep going.”

Although many traditional weavers were outraged at the self-taught Tawney, she was grouped in important shows with Mark Tobey and Georgia O’Keeffe. Patrons like the Rockefellers came and went. Meanwhile, Tawney kept traveling and receiving attention in art journals, but high visibility eluded her then as now.

“Lenore’s priorities have always been on the development of her work and not her presentation of it,” says Paul Smith, director of the American Craft Museum. “She would never get her slides together and go to an agent.” Says Tawney, “I don’t care if I sell, because my husband’s income freed me. If I had to sell my work, I couldn’t have done these innovations. People aren’t ready for them.”

Nevertheless, living a life of cosmic patience in which art is god can clash with the material world where art is hot commodity. Tawney, whom Smith rates as “absolutely underrecognized,” understands that her dedication to art has carried with it the condition that she also lead “an impersonal life.” But one does come away with the impression that this woman of extremes would like her sacrifice recognized by the public. Never mind the divine contradiction.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.