Newsweek – June 13, 1977

In the tropics one must before everything keep calm. – Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

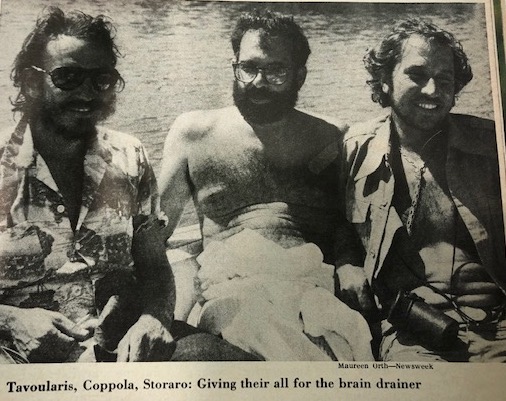

It was the middle of the day in the steamy Philippine jungle and the sun was merciless. Director Francis Ford Coppola, dressed in rumpled white Mao pajamas, was slowly making his way upriver in a motor launch. “Right here is where we hang the dead body,” he said to his production designer, Dean Tavoularis. “I want skulls – a pile, no, a wall of skulls.” “Can we light this for night?” he asked his director of photography, Vittorio Storaro. Storaro sighed and stroked his beard. “Fires should be burning behind the curtain,” Coppola said to Tavoularis, pointing to a striking red silk curtain that meandered 300 yards along the riverbank. When the boat docked, a set decorator complained, “Where are we going to get 200 skulls?” Tavoularis shrugged. After what he and everyone else had been through, 200 skulls were just so many coconuts.

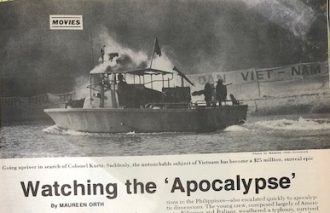

For over a year, one of Hollywood’s most successful directors (“Godfather I and II”) had been shooting “Apocalypse Now,” a film about the “untouchable” subject of the Vietnam war. It had started in March 1976 as a $12 million movie that would take four months to shoot. Things quickly escalated. By the time the crew finally left the Philippines a fortnight ago, they had become battle-scarred, if well paid, veterans. “Apocalypse Now” had consumed more than 230 shooting days and a million feet of film and will end up costing about $25 million. (A little more than $7 million came from the sale of distribution rights in foreign countries; United Artists says it has put up $7.5 million and advanced the rest to Coppola, who has put up all his own assets as guarantees on the loans.)

Life on the set – four different locations in the Philippines – also escalated quickly to apocalyptic dimensions. The young crew, composed largely of Americans, Filipinos, and Italians, weathered a typhoon, survived dysentery and sweated through day after day of relentless heat – alleviated by periodic R&R trips to Hong Kong. Stuntmen amused themselves by diving from fourth-story windows into the motel pool below. The prop man, Doug Madison, became adept at fabricating top secret CIA documents, thought nothing of driving 400 miles to fetch a special Army knife, and made a connection with a supplier of real corpses – before he was vetoed. At one point, Coppola asked Tavoularis to produce 1,000 blackbirds, which prompted the designer to consider making cardboard beaks for pigeons and dyeing them black. The film company retained a full-time snake man, who appeared every morning on the set with a sack full of pythons. The Italians brought in pasta and mozzarella from Italy in film cans. Did Coppola want a tribe of primitive mountain people living on the set in their own functioning village? He got it.

REPLAY OF A NATIONAL NIGHTMARE

At night, General Coppola reviewed video cassettes of the film in his house in Hidden Valley, a volcanic crater, arriving there in a helicopter that he often piloted himself. By the time he finished shooting, he had lost 60 pounds, and the making of “Apocalypse Now” had come to resemble nothing so much as its subject – Vietnam.

For years, Hollywood has ignored Vietnam on the theory that nobody wants to see America’s worst national nightmare replayed. Now, a number of movies are being made about the war, but none so far-reaching as “Apocalypse.” The original script was written in 1967 by John Milius, an unregenerate hawk, but Coppola has reportedly long since abandoned all but the story line to move closer to the script’s original source, Joseph Conrad’s classic study of moral jungle rot in Africa, “Heart of Darkness.” Coppola’s idea has been to make the film on two levels – both as an entertaining war movie full of action, adventure and spectacular special effects, and as a mythical, highly stylized allegory of the American experience in Vietnam in 1968 and 1969 – all of it set to the rock music of The Doors and filled with psychedelic sound and light.

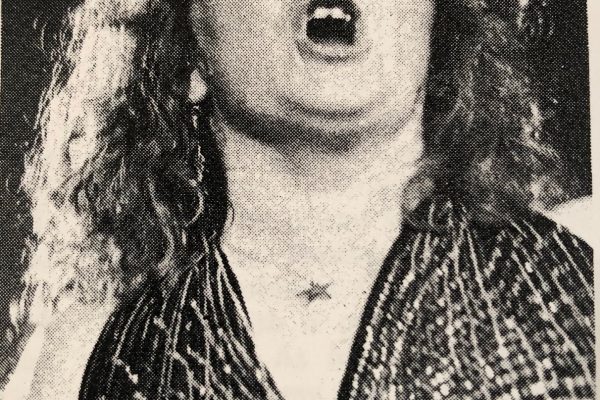

Martin Sheen plays Army Capt. B. L. Willard, hired by the CIA and sent upriver on a Navy patrol boat crewed by Frederic Forrest, Sam Bottoms, Larry Fishburne and Albert Hall. His mission is to kill Coppola’s “Mr. Kurtz,” one Col. Walter E. Kurtz – an officer gone insane – who lives in a temple resembling Angkor Wat across the border in Cambodia, is worshipped by the Montagnards and is played by Marlon Brando.

One of Kurtz’s entourage is a spaced out hippie photographer who’s had about 200 acid trips too many, a role Denis Hopper evolved for himself. Robert Duvall plays another kind of mad colonel who carelessly risks the lives of his men in order to land in a village that has perfect waves for surfing. As Sheen and his crew head upriver, they encounter a wild rock concert during which 300 horny soldiers storm a stage to get at a delegation of Playboy bunnies; a French plantation family determined to hold out at all costs; exploding bridges, and one peaceful group of Vietnamese whom they murder in panic. One helicopter battle sequence, choreographed to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” took seven and a half weeks to shoot and will appear on the screen for only six minutes.

A FILM ON TWO LEVELS

“I am doing this film half intuitively,” says Coppola, sitting inside his houseboat, where he wrote out the script each day on index cards. “I am spinning a web. The movie has two levels – the level of the life on the boat and the mission and then what happens to Kurtz’s mind when the film becomes a surreal. His mind is blown by the extent of the horror of the war. You have to invent. All I do is see more or less what the truth was and put it in the movie. Of  course, the movie has to live in reality and practicality. I’m spending $100,000 a day. Imagine the degree of control I have to have.”

course, the movie has to live in reality and practicality. I’m spending $100,000 a day. Imagine the degree of control I have to have.”

That control wasn’t always easy – to say the least. The first phase of “Apocalypse” ended when the typhoon struck, destroying sets that had taken months to build and stranding the crew in various isolated locations. (One group found itself stuck in a house with a Playboy Playmate, who shut herself up in a room, declaring, “I can do without sex for nine months.”) Even before the typhoon, Coppola fired one of his leading actors, Harvey Keitel, who hated the jungle and couldn’t stand bugs. On the first day of shooting, Keitel and the other actors had been unintentionally left by the camera crew in the middle of the river. “Hello,” announced Keitel fruitlessly into his walkie-talkie. “Hello, this is Harvey Keitel.” Silence. “This is Harvey Keitel.” Silence. Then: “You wouldn’t do this to Marlon Brando. You wouldn’t do this to Marlon Brando.”

“It was hell for a while at the beginning of the movie,” says Gary Fettis, a crew member. “Mostly because Francis was getting ripped off by the Filipinos. Artistically, Francis didn’t know what he was going for and he was a pretty hard guy to be around. The crew didn’t know he didn’t know. But when you’d see him typing away in his houseboat in the mornings, you suspected as much. It created a sense of chaos.”

When Brando showed up last fall with an entourage of seven (his fee for five weeks’ work was $1 million), Coppola still hadn’t written the ending to the movie. He finally shut down production for a few days to talk about Conrad with an old pal from film-school days at UCLA, Dennis Jakob, a fanatical lover of Nietzsche’s philosophy who became the movie’s intellectual catalyst. He also spent hours discussing the war in Vietnam with Brando, and tapes of those conversations figure in the film.

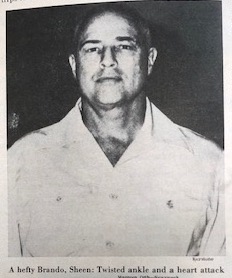

A 285-POUND STAR

“I tried to write the end in which Kurtz goes mad, over 100 times,” says Coppola, “but I didn’t know what Marlon would look like or how much he would weigh. I went to bed every night at 4 a. m. and told my wife, if she was there, ‘I can’t write it, I can’t write it’.” In fact, Brando showed up weighing 285 pounds, so Coppola decided to make Kurtz 6 feet 5 inches and do most of his body shots using a 6 foot 5 inch double, a coloful ex-boatswain’s mate in  Vietnam named Pete Cooper who ran the boats for the crew and served as military adviser to Coppola. Brando shaved off all his hair for the role and requested 5-inch lifts on his shoes to get the feel of the part. On the first day he wore the lifts, he twisted his ankle and retreated at once to his trailer.

Vietnam named Pete Cooper who ran the boats for the crew and served as military adviser to Coppola. Brando shaved off all his hair for the role and requested 5-inch lifts on his shoes to get the feel of the part. On the first day he wore the lifts, he twisted his ankle and retreated at once to his trailer.

Members of the crew refused to ride in a bus with Dennis Hopper, who wore the same set of clothes for the two months he was there. Last March, Keitel’s replacement, Sheen, a 36 year old physical-fitness buff, suffered a heart attack during a 6-mile jog in the 100 degree heat. Sheen, who recovered six weeks later, thinks his attack was precipitated by his own death fears triggered by working on “Apocalypse Now.” “The film really scared the hell out of me,” he says. “I discovered through my sickness that I was acting out my mother’s death. She also died thousands of miles away from home of a heart attack.”

Coppola was forced to rely on the Philippine military for personnel had equipment, since the U.S. Department of Defense refused to cooperate with the project in any way. (Coppola sent angry cables to Washington, D. C., claiming that Defense was harassing him.) On the first day of the big helicopter scene last summer, according to some reports, a Filipino officer pocketed the $15,000 out of which he was supposed to pay his pilots, and the next day the pilots refused to work. Almost every day thereafter, they made new demands for money on the film company – which had come to be regarded in the local countryside as a cross between an invading army and Santa Claus.

Pagsanjan, the sleepy river town north of Manila where the “Apocalypse” crew had its headquarters, had been accustomed to an average wage of less than $2 a day. But for nine months, the movie company pumped in $100,000 a week there. As a result, the robbing of local coconut plantations stopped, rents for homes shot up astronomically, and every night the high-school principal, Ricardo Fabella, went from bar to bar in his jeep urging the Filipino film workers not to waste their windfall wages on liquor and women. “Our people have lost their sense of values,” he said. “Everything I’ve taught them they’ve forgotten.”

At one lavish party Coppola threw to thank the residents of Pagsanjan for their cooperation, he heard himself praised by the governor of Laguna Province as the best ambassador the U.S. ever sent. The next speech was from the local prosecutor who, before he picked up the microphone to sing with the band, mentioned two lawsuits against “Apocalypse” – one for the mutilation of birds (both suits were later dropped). He turned over the mike to Coppola, who serenaded the crowd with “‘A’ You’re Adorable.” “It’s either here or Beverly Hills,” Coppola called to his wife. “Let’s stay here.”

EVERYTHING BUT REAL BULLETS

Because of the film’s vast arsenal of explosives and weapons, the set was heavily guarded at all times. Coppola was driven by a member of President Ferdinand Marcos’s personal staff. For one scene involving 2,000 South Vietnamese troops and villagers, the film-makers recruited several hundred South Vietnamese refugees. The Philippine Government supplied eighteen helicopters, which were outfitted with new rotor blades and converted into gunships for the Philippine Air Force at the film company’s expense. Dick White, an ex-Vietnam helicopter flying ace and daredevil, supervised the air sequences. “This movie has everything but real bullets,” he says. “With my helicopters, the boats and the high morale of the well-trained extras we had, there were three or four countries in the world we could have taken easily.”

But the longest running real battle on the set was over what the film was really about. “What Francis is trying to say,” says Brando’s stand-in, Pete Cooper, “is that the military people were not second-class citizens and idiots. They were good hometown boys, but the war changed them. The whole military image is going to be changed after this.” “I hate to say it,” says special effects chief Joe Lombardi, “but this whole movie is special effects. You got three stars but the action’s gonna keep the audience on the edge of their seats. It’s a war movie.” “This movie’s about how wrong it was for Americans to go against their nature,” says Dean Tavoularis.

Still, everyone was loyal to the general. One of Coppola’s skills as a director was that he was able to make everyone give his all.” Francis wanted to get me and Dick White drunk and listen to war stories,” says Cooper. “I didn’t want to. For the first four months of this film I was screaming in my sleep – reliving it all. But in the military you’re taught to follow orders. Francis is a brain drainer. You sit with him for ten minutes and he absorbs everything in your body.”

It’s hard to say who gave the most, but nearly everyone agrees that a great catharsis came at Kurtz’s compound – a hot and humid pit a half mile long. The temple inside the pit was destroyed by the typhoon, and was reconstructed with 300-pound blocks placed mostly by hand. To express Kurtz’s “horror,” Tavoularis, who describes his life as “a shambles” after working two years on the film, let his feelings of depression and alienation run wild. He piled up garbage. He spread blood and skulls all around. He got old bones from a restaurant in Manila. Rats arrived on the set and people began to complain of the stench of festering flesh.

“Francis and I reached the same point through different channels,” says Tavoularis. “We both did it by going through a certain madness. He was feverishly rewriting the whole end of the film, talking to Marlon and Dennis Hopper. I was living the house of death I was making. It became such a low level in my life that somehow putting blood on staircases and rolling heads down steps seemed natural to me.” The experience went on for weeks. “There were times,” remembers Delia Javier, a Filipion crew member, “when I feared the consequences for my psyche. Then one night everything fused together. It was what Christians call a miracle.”

Part of the credit for the miracle goes to 250 fierce and primitive Filipino mountain tribesmen, the Ifugaos, still head-hunters during World War II, who were brought from the north to live on the set at Kurtz’s compound. “People said the Ifugaos were very calming in the craziness,” says Eva Gardos, a former Harlem schoolteacher, who was sent to the mountains of the northern Philippines to find “some primitive people” at Coppola’s request. In order to lure the Ifugaos south, Gardos promised them a weekly supply of betel nuts and, in case any of them got sick, live animals for sacrifice.

FOUR BLOWS OF THE KNIFE

Brando invited the Ifugaos to his big welcoming party, complete with ice Oscars lighted from inside, spectacular fireworks and a magician. They loved the fireworks. Coppola incorporated Ifugao ceremonies and dances into the film; they were also taught to use guns and to sing – phonetically – ‘The Doors’ “Light My Fire” to the accompaniment of their own instruments. Although they generally were shy, one teenage Ifugao girl got friendly enough with make-up man Fred Blau to ask if she could borrow his tape of John Denver’s “Greatest hits.”

In honor of Coppola, the Ifugaos re-enacted their sacred sacrifice of a water buffalo and Coppola has used this on film as one of his story’s most important symbols. “First the Ifugaos talked to the water buffalo for two days and told it not to be afraid of death,” reports one extra. “Then they killed four pigs and sacrificed a chicken. The meat was passed around and eaten, sometimes raw. Then the elders took long knives and gave the buffalo four blows at the back of the neck. During this time the water buffalo didn’t utter a sound, but he had a big tear in his eye – he really did. Wham, the fourth blow killed him. In the film, Sheen kills Brando the same way.”

Is America ready for “Apocalypse Now”? Just to make sure, United Artists is paying a half million dollars on two political miracle workers – Jimmy Carter’s media consultant Gerald Rafshoon and pollster Pat Caddell – to help Coppola’s staff devise a marketing strategy for the three-hour-plus film. The film is scheduled, if all goes well, to open in Decemmber. It will be shown on a reserved-seat basis at increased admission prices. Caddell’s poll ranges from measuring the impact of Vietnam to finding out how many people know the meaning of the word “apocalypse.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.