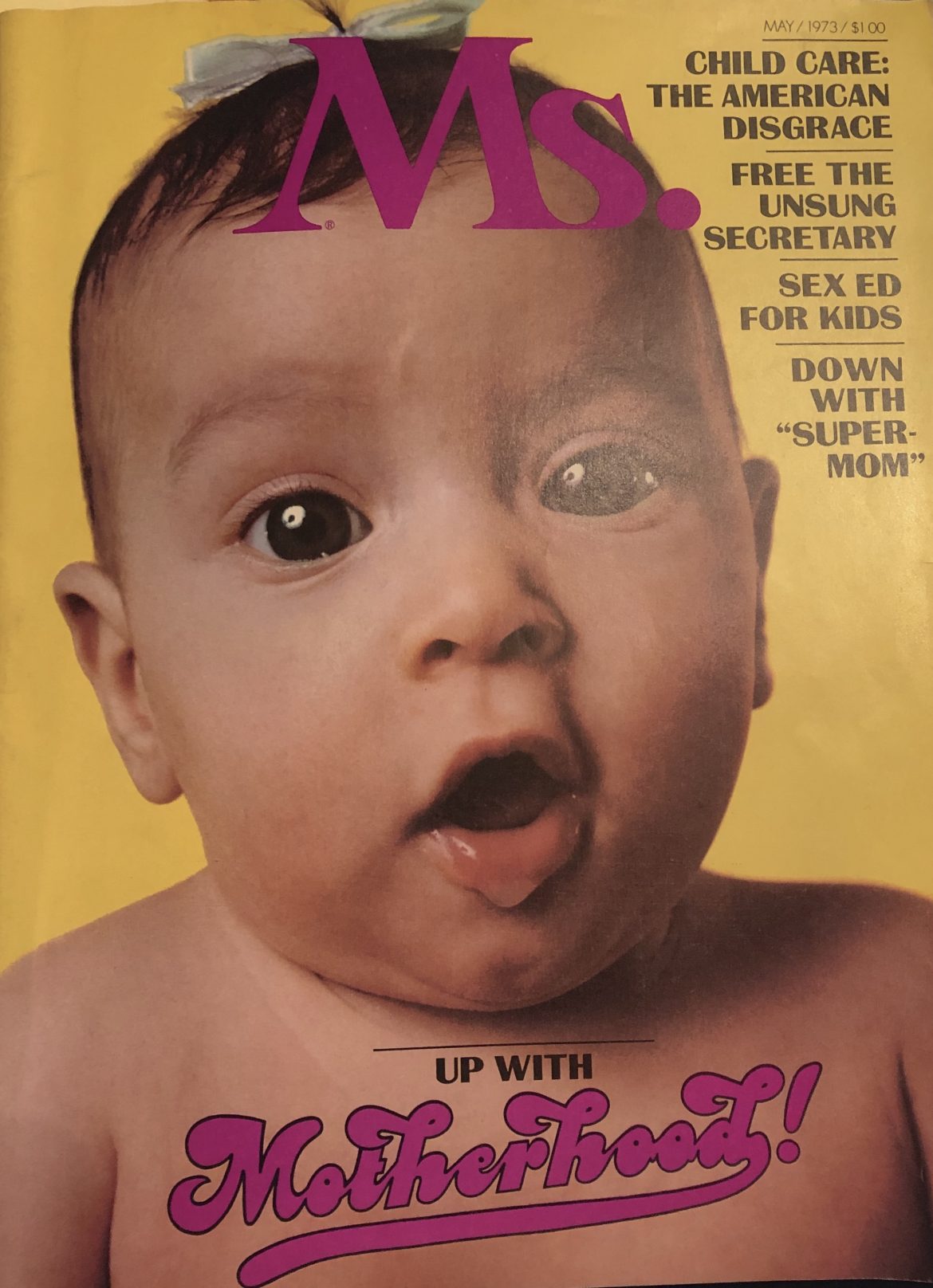

Suffer the Little Children . . . The American Child-Care Disgrace

Original Publication Ms. Magazine May 1973

“So critical is the matter of early growth that we must make a national commitment to provide all American children an opportunity for healthy and stimulating development during the first five years of life.” – Richard M. Nixon, the President’s message establishing the Office of Child Development, January 1969.

“Neither the immediate need nor the desirability of a national child-development program of this character has been demonstrated . . . For the federal government to plunge headlong financially into supporting child development would commit the vast moral authority of the national government to the side of communal approaches to child-rearing over against the family-centered approach.” – Richard M. Nixon, the President’s veto message on the Comprehensive Child Development Bill, December, 1971.

In Chicago, a day-care center licensed to care for 18 children was found to have 51 infants strapped in cribs and high chairs – with only one employee to care for them.

- In Los Angeles, some mothers who must work outside the home have become so desperate that the leave their children with junkie babysitters, knowing that a cash payment at the end of the day will bring the addict back the next morning.

- In Cleveland, there are so many children who come home from school to an empty apartment, but who are too little to be trusted with loose keys, that neighborhood stores sell chains for the purpose of hanging keys around the necks of these “latchkey” children.

- In Detroit, a working mother discovered that her small daughter was being physically abused by the neighbor – herself the mother of many small children – with whom she had been leaving her for a year.

- In New York, a report on police efficiency found this interesting problem with patrolmen on the night shift: they failed to make arrests that would require their presence in court during the day. Their wives work, and the men must be home with the children.

These examples are heartbreaking but not unusual. They can be multiplied across the country thousands, millions of times – a testament to our inability to deal with a fundamental human need.

Today we have more working mothers than ever before, more than twice as many as in 1950, and the figures are expected to double in the next decade. Nearly one-third of all mothers with preschool children and half the mothers with children 8 to 14 are working. Each year, more and more research piles up attesting to the importance of learning in the first five years of life. We live in a country that pays lip service, at least, to the idea that the welfare of the child is a basic human right. Yet we have no national network of subsidized quality child-care centers (not day care, which assumes all people’s needs fall from 9 A.M. to 5 P.M.) where parents can be sure their child will be able to develop her or his potential, will receive health care, hot meals, preschool education, and personal attention – a full range of developmental services plus the opportunity to relate to and learn from a variety of adults and children. Child care, of course, must not be tied exclusively to the needs of the working mother. The father, too, has an equal need – whether he is raising children alone or is the only wage earner in a family that desperately needs a second income. And children have the greatest need of all. Our goal should be free, universal, consumer – (this means parents) controlled child care, where children, even rich children, have the daily companionship and learning opportunity of being with their peers as well as their parents.

But instead, we have millions of children, at least eight million in desperate need, who should be in centers but aren’t. Many are cared for by a succession of untrained baby-sitters. Others have brothers and sisters who are forced to drop out of school to care for them. The notion of aunts and grannies in the home who love to take care of little children just isn’t true any more. Estimates of latchkey children run as high as a million and a half. No one at all takes care of them. But they often show up later as other kinds of statistics, in juvenile delinquency cases and drug-addiction centers. Then we pay highly for their care.

There’s nothing so radical about the idea of making voluntary child-care programs available to American parents and their children. During World War II, for instance, the government cheerfully paid for child-care centers for more than a million-and-a-half children whose mothers were working in defense plants. Currently, however, the only justification for subsidized child care that the government will accept is to get off the welfare rolls – a goal that results in isolating poor and minority children in custodial centers so that their mothers can be forced to work.

We shouldn’t have to declare World War III to understand children have basic human rights. The constituency for child care is no less than the parents and children of America. Yet despite the serious need for early childhood development, there is little action. Why is child care a dead issue in Washington today?

“I’ve spoken to hundreds of women across the country, rich and poor, women who make $20,000 a year – women whose lives have been blighted because they have been unable to find satisfactory day care,” says Dr. Edward Zigler, a Yale professor of child development, who is the former head of the Office of Child Development at the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. “What’s happened to their children? Almost 50 percent of all mothers work, yet so far they haven’t exerted pressure on the government. I am convinced it has to do with the downtrodden nature of women in America. They feel this is the way things are supposed to be. They’re supposed to be put upon. Farmers and the aerospace industry fight for their interests and get billions of dollars worth of subsidies. The government helps them, but doesn’t help mothers. We’ve so conditioned women to get the short end of the stick that they think it’s the plight of women to suffer, and they don’t expect any action.”

Zigler’s observation offers some insight into at least one of the reasons why the Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971 – a bill of direct benefit to millions of mothers, fathers, children, and employers; a bill which passed Congress but was vetoed by President Nixon – never caught fire in the grass roots, and didn’t receive the lobbying support it needed to survive. (Simply put, the bill would have extended downward the age at which a child is eligible to attend school. Parents would have had the option of placing children of two-and-a half, and even younger, in child care facilities that offered education, nutrition, and health programs. The services, including prenatal care, were to be available to the middle class as well as to the poor. Although the bill fell short of providing free care, since all persons earning over a specified income would pay on a sliding scale, it would, nevertheless, have established the beginnings of a socially and economically mixed preschool system.)

While women continue to suffer because of the overwhelming difficulty of finding affordable, quality child-care arrangements, they may keep their suffering hidden, even to themselves. Many women are tortured by guilt when they leave children in the care of others, no matter how justified the reasons or how educational for the children. They don’t think of turning to the government for help. Somehow we have so indoctrinated women with the sacred, romantic myth of motherhood (significantly, not parenthood) plus the ideal of the nuclear family, that they are reluctant to admit when they need help and reluctant to demand that some of their tax dollars go toward child care. As long as the American mother has feelings of guilt and is unable to see child care as more than a personal problem, the politicians will continue to ignore her and the basic rights of her children.

But women are not to be blamed out of proportion to their real political power. The failure of child-care legislation goes beyond lobbying.

“Child-care programs could ultimately cost $20 billion a year; in 1972, over-runs on defense contracts cost $29 billion”

Obviously an adequately funded child care and development program costs money – an estimated $20 billion a year to fulfill today’s needs. “You won’t get twenty billion in a decade,” asserts an aide to the Senate Finance Committee, “because the American taxpayer doesn’t care that much about kids.” But this figure does not seem hopelessly huge when compared with other government figures – particularly items in the Department of Defense Budget. There, cost overruns on military contracts – not the contracts themselves – ran to more than $29 billion in 1972 alone.

Another obstacle in the path of subsidized child-care is the fact that the majority of the lawmakers and Administration aides charged with deciding the fate of crucial legislation are men past the age of parenting. They seem unable to grasp what it means to be a 32-year-old wage earner responsible for three children under the age of eight. This insensitivity, fortified by the scare rhetoric of the right wing (“the sovietization of American youth,” “the final fatal step towards 1984”), places any concept of comprehensive child care in jeopardy. The opponents of federal child-care programs, furthermore, write letters to the White House and to Congresspeople far out of proportion to their numbers. And the media, responsive to the issue only during volatile, after-the-fact confrontations, have not been persuaded to provide the ongoing coverage so needed to communicate the philosophy and significance of government involvement in child care.

According to Edward Zigler, “Any legislation as fundamental as the Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971 cannot succeed without a substantial national dialogue. The woman in Dubuque and the man in Los Angeles have to grasp the issue.” Given the media’s apathy, the inability of put-upon parents to form an effective, visible lobby, plus the savvy of the issue’s professional foes, the President’s veto becomes less surprising.

If we are to fight successfully in the future for quality child-care programs, a recap of the legislative fate of the Comprehensive Child Development Act affords some valuable lessons.

The bill originated in Congress, which made it unique and problematic from the start. (The Executive is accustomed to initiating major legislation.) For over a year, the Administration could not decide what position to take. Health, Education and Welfare – the agency charged with administering the bill – was being asked to create both philosophy and bureaucracy at once, in addition to carving out a whole new sphere in American education, subject to a wide range of special interest groups (from textbook salespeople to a vast new children’s lobby). Yet by the summer of 1971, everyone was cautiously predicting the bill would become reality.

But liberals in the electorate (who formed the “day-care lobby” as it was called) and liberals in the Senate toughened their position on consumer control. They wanted funds to flow in a direct federal-local relationship to child-care centers, thus bypassing involvement of the state governments. (Remembering Mississippi, for example, which held back progress in Head Start because the programs had to be integrated, they decided not to let history repeat itself.) But Republicans and some moderate Democrats felt the states should be involved, that exclusion constituted a violation of states’ rights, and that direct funding would create a “vast (federal) bureaucratic army.” Powerful Republicans in Congress warned that the cutting out of the states would lead to a veto. In order to preserve the original bipartisan nature of the bill. Representative John Brademas (D-Ind.), the bill’s mentor in the House, sought to maintain some role for the states.

In the end, though, the liberals were able to maintain “consumer control” provisions intact. Many Washington observers believe their refusal to give on this point resulted in winning of the battle only to lose the war.

The final version of the Comprehensive Child Development Act was reported out of the joint Senate-House Conference Committee with the stipulation that any locality over the size of 5,000 could apply for direct funds from the federal government, thereby limiting the states to a mainly technical or advisory role. Most of the Senate Republican leadership voted for the bill anyway, knowing it would probably be vetoed. Many had cynically voted for passage because, after all, who wants to vote against little children with an election year coming up?

When the bill arrived on President Nixon’s desk for signature, it landed among thousands of letters peppered with such phrases as “the heavy hand of government in every cradle.” The proponents of the bill organized into a 23-group coalition led by Marian Wright Edelman., Director of the Washington Research Project, had not convincingly demonstrated (to Mr. Nixon’s satisfaction) what they knew to be the needs of so many American families.

Although Patricia Nixon was then Honorary Chairperson of the Day Care and Child Development Council, one of the staunchest advocates of subsidized child care, Richard Nixon pandered to the conservative outcry (perhaps mindful that the conservatives were also angered over his trips to China and Russia) and struck down the Comprehensive Child Development Act. In an inflammatory veto message, he chose not to commit “the vast moral authority of the national government to the side of communal approaches to child-rearing over against the family-centered approach.” It didn’t seem to matter that the veto message contradicted one of the President’s pet pieces of legislation at that time, the Welfare Reform Bill, “H.R. 1” – which sought custodial child-care facilities for the children of welfare mothers so they could enroll in work-training programs. Without child care, what chance would there be to get these women off the dole? Evidently, it was all right to “break up” the families of welfare recipients to get them to work, but those mothers of middle-class families who were already working would be forced out of the labor market.

While Marian Wright Edelman’s coalition worked hard to promote the bill, they, in the words of Washington reporter John Iglehart, “never sold day care as a middle-class need. Most politicians don’t see day care any differently than any other OEO (Office of Economic Opportunity) liberal, bleeding-heart program.” According to Theodore Taylor, Executive Director of the Day Care and Child Development Council of America, “There (was still) the sense that child-care institutions undermine the stability of the family and that child care or child development is really only an adjunct to welfare.” So the massive, three-year-long struggle that spanned thousands of pages of testimony, endless conferences and meetings, and hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars of staff time was scratched with one stroke of the Presidential pen.

Because the Administration’s attitude toward child care has hardened so much in the time since the veto, it now seems almost utopian to think that developmental child care ever had a chance of becoming law. Since the veto, major governmental effort in the child-care field has been a part of the insidious design to provide custodial baby-sitting for the children of welfare mothers, but only for those mothers on work-training programs. Spaces for their children would come, not through the creation of new facilities, but from the elimination of the children of the working poor and middle class who are already in subsidized centers.

Now, “revenue sharing” is the new code word used in government to dismiss queries about instituting a national network of child care. Under revenue sharing, each state receives a check from the federal government to spend as it wishes. The Administration purports not to care if the states spend the money on child care or lowering property taxes or paving highways. The practical consequence of revenue sharing, though, has been to pit all the social-welfare programs that receive federal moneys – but which are now under a spending ceiling limit – against each other. As a result, drug-rehabilitation programs are fighting the elderly who are fighting the handicapped who are fighting child-care people – all for limited funds.

This is so because, under the legislation passed by the last Congress, social-welfare programs that previously received matching funds from the federal government are subject to a $2.5 billion spending ceiling. The child-care money that used to come out of Title IV-A and IV-B of the Social Security Act is also part of that limit. Formerly, if state and local governments or private local donors could come up with 25 percent of the money to fund a child-care center, the federal government would foot the additional 75 percent – providing a center met certain criteria. There was no upward limit on the money the states could apply for. Few states, however, took advantage of the law, which also stipulated that Title IV-A and B funds were for “any kind of service that was rehabilitative or preventive in nature for past, present, or potential welfare recipients.” However, New York liberally interpreted that definition and began setting up child-care centers for middle-class children; Mississippi went even further – it saw the legislation as a way to practically fund their state government. Congress plugged that loophole. And in February, the Administration introduced regulations that would severely restrict the eligibility of a past or potential welfare recipient. Previously, a “past” recipient was defined as someone on welfare within the last two years: this may be changed to the last three months. A “potential” welfare recipient was someone who, without child care, would go on welfare in five years – this may be changed to six months. There was even a proposal – since abandoned – to prohibit the use of private money to get matching funds. This would have been especially damaging to poorer states that have no hope of generating child-care funds from their own revenues. As one Administration official, summarizing the current Nixon philosophy of government spending and social welfare, put it, “You’ve got to get the right bang for the buck.”

Today we are in the paradoxical position of having the number of children who require child care dramatically increasing and the number of federal government “slots” in child care decreasing. The new restrictive guidelines hit hardest at the working poor – women who have struggled valiantly to stay off welfare. “Day-care prices most frequently quoted are $25 to $36 a week,” one mother of a three-year-old child told me. “Since I take home $100 a week, this is impossible.” If their children are no longer “eligible” for subsidized child-care facilities, many parents who are now classified as working poor will have to quit their jobs and be forced to rely on unemployment and eventually welfare. Is this “the bang for the buck” the Administration is seeking?

When asked by a reporter about the fiscal irresponsibility of eliminating child-care slots only to have state and federal government pay more money out in welfare and unemployment, an administrator of the Office of Child Development at HEW replied, “That is an excellent question without an answer. That kind of consideration makes eminent good sense to you or me, but God knows why OMB (Office of Management and Budget) did it.

Joan Hutchinson, Special Assistant to the Acting Administrator of Social Rehabilitation Services at HEW, which is the office that administers Title IV-A funds, did have an answer. “Women need to understand the hard realities fiscally and operationally,” she explained. “Child care has expanded rapidly in the last two years, but fiscal limits are being imposed for those who need it most. We don’t know what’s going to happen. You have to make your choices based on cost benefits.”

The morality of “cost benefit analysis” has effectively stopped the creation of new child-care facilities across the country, threatened the existing quality of child care received, and perpetuated a vicious cycle isolating the poor. Though revenue sharing purports to throw the burden of providing child-care services to the states, the states have not had an impressive record of achievement in establishing new child-care facilities, licensing private day-care homes, or training personnel to staff the centers.

Although the once lofty hope of comprehensive childhood development has been reduced to a repressive social-service concept connected to the employability of welfare mothers, we do not lack legislators eager to sponsor bills that would guarantee to all young children vital health and educational services. What the Brademases, Mondales, Reids, Hecklers, Chisholms, and Abzugs in Washington need is tangible support at the community level. We must continue to make our needs known to our mayors, city councils, governors, and state legislators. They in turn will be forced to demand federal relief. For example, Mary Sansone of New York City, representing the Congress of Italian-American Organizations (CIAO), informed the local establishment that they could cross off the support of Italians on election day if much needed child-care facilities weren’t forthcoming. She even went to Washington to lobby powerful national legislators. Wilbur Mills, Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, showed how child care is, in many legislators’ minds, connected to welfare and minority stereo-types: he astonished her by saying, “I wasn’t aware that Italians needed help.” But, because of her and the Organization’s persistence, CIAO has obtained funding for three centers.

A larger grass-roots effort must also be made to overcome the indifference to inadequate child care and the die-hard myths, particularly the guilt-inducing exclusivity of parenting, that prevent a commitment to early childhood development programs. “Advocates of free, universal child care would do well to focus on consciousness-raising about child care and finding a legislative vehicle which will enable Congress to spend money without seeming to be helping ‘the poor’,” advises William Pierce, Director of the Washington office of the Child Welfare League of America. He suggests a possible legislative vehicle: “Attach child care directly to education. California already has (some) child care connected to education. Bipartisan action might be possible for some bill (in 1974 but not before) which uses the California experience as a model.”

Can we wait yet another year? Another year of vital human needs going unmet? of latchkey children roaming the streets? of substandard baby-sitting services? of prevailing upon a grandmother or a neighbor who may already have too many children of her own? of middle- and upper-income children who vegetate by the television set?

American parents must start asking why.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments