Original Publication: Newsweek — March 29, 1976

Hollywood is currently so action-crazed and disaster-dazed that it’s a welcome relieft to see three new films from France about nothing more than real people. There’s plenty of action in Salut L’Artiste; Vincent, Françoise, Paul and the Others, and French Provincial, but it’s mainly of the interior sort – the ricocheting of human lives in their middle years when older is not necessarily wiser.

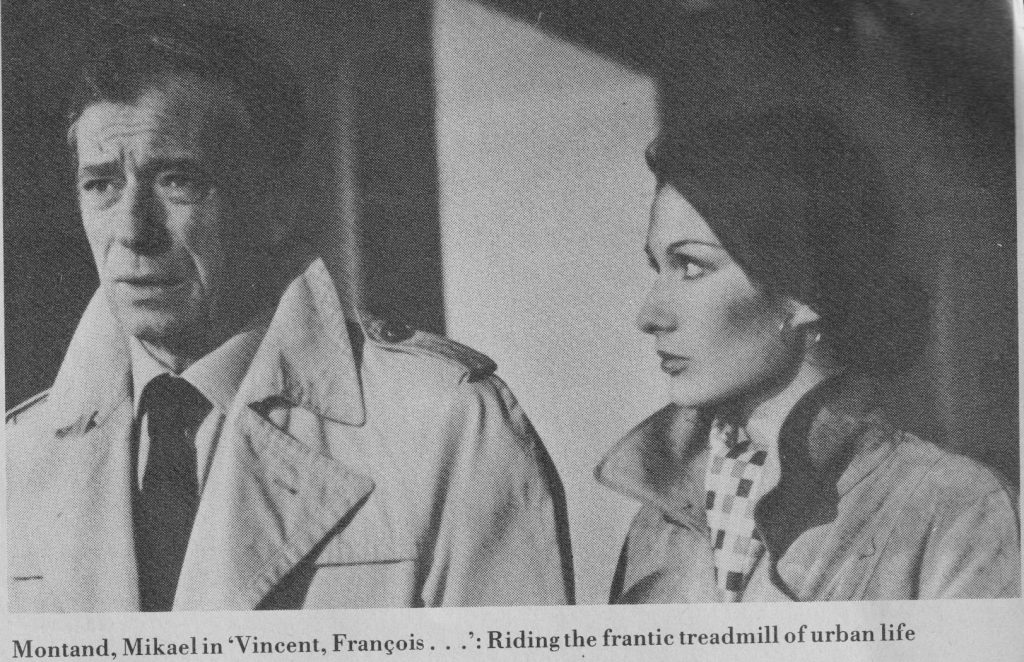

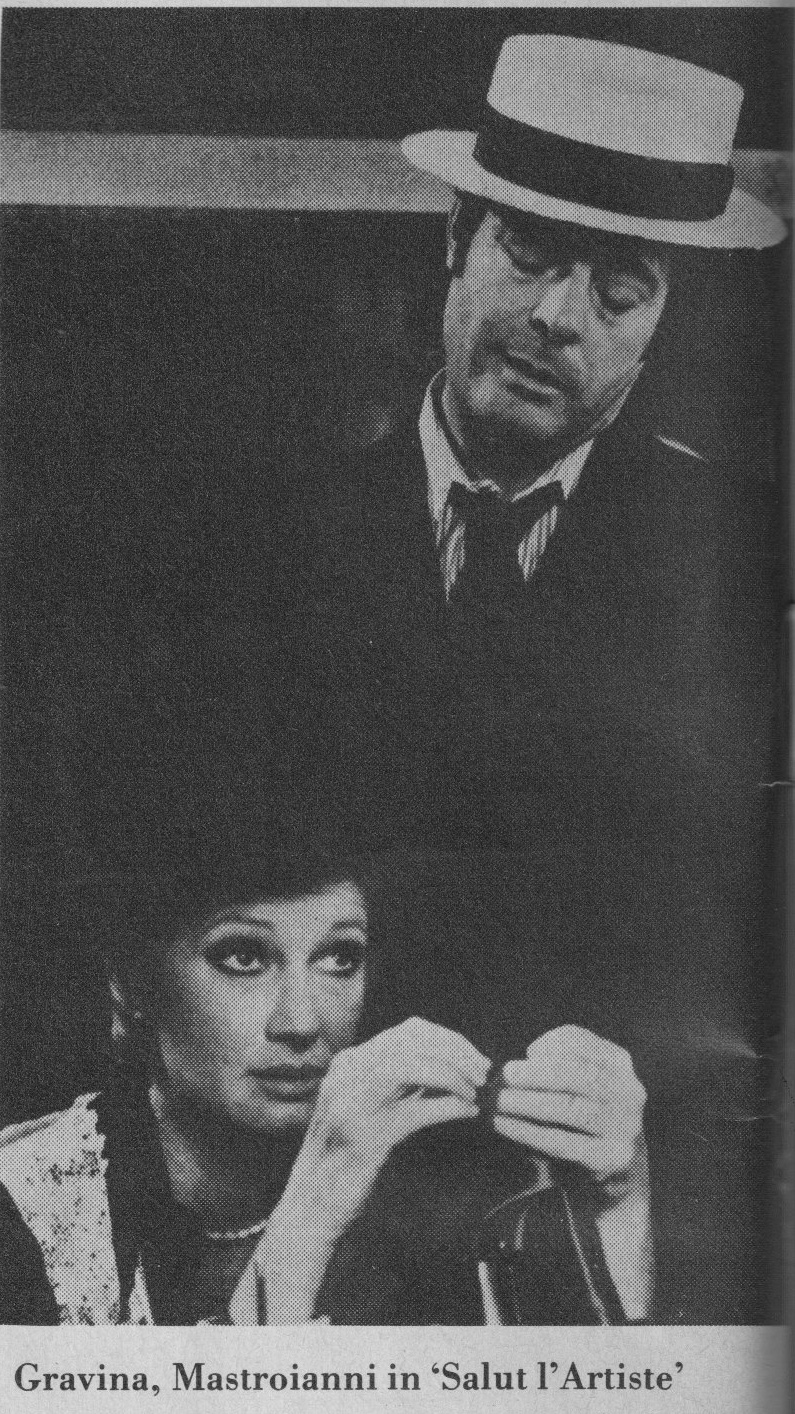

Part of the charm of these films is that their stars – Marcello Mastroianni, Yves Montand and Jeanne Moreau – refreshingly refuse to hide their ages. In “Salut L’Artiste,” Mastroianni plays a bewildered buffoon, a bit actor over 40 whose life and art have come down to one dumb act. In “Vincent, Françoise, Paul and the Others,” Yves Montand wears a mask of ironic bravado over the failed aspirations of a fiftyish bourgeois businessman. In “French Provincial,” Jeanne Moreau is a brassy little seamstress whose purchase on the world is not Circean glamour but shrewdness.

As directed by Yves Robert (“The Tall Blond Man with One Black Shoe”), Mastroianni is a transplanted Italian in Paris, the Gallic version of the aging Sunset Strip habitué whose French jeans don’t quite fit and whose turquoise necklace looks like its choking him to death. All day long he rushes through costume changes: in the afternoon he takes an arrow in the chest as a Roman soldier, in the evenings, a bullet onstage as a cop, and afterhours winds things up with a magic act in a topless bar.

His identity gets lost on the way. Using stage speeches for his roles as husband, lover, and father, he can’t figure out if he’s dropping in or out of life. Worse, when he’s at his most sincere, everybody – ex-wife, mistress and partner – laughs at him. L’artiste doesn’t get the joke, and he never will. Instead, he keeps telling people he’s “evolved.”

Flesh: As romatic comedy – another rare film species today – “Salut L’Artiste” is not very “evolved” either. But because its characters seem made of flesh and blood, because they don’t fit the current American pattern of being either psychotic or mannequins of old movie stars, its’ enjoyable – a perfect matinee movie. It is also welcome for the decidedly un-American presence of two women characters who are not just beautiful but intelligent, Carla Gravina as the ex-wife, Françoise Fabian as the mistress.

“Vincent, Françoise, Paul, and the Others” is a more ambitious and successful attempt to depict quietly desperate characters riding the frantic treadmill of contemporary urban life. Director Claude Sautet, like Hollywood’s Paul Mazursky, likes to dissect the sagging bourgeoisie. Vincent (Montand) has left his wife (Stéphane Audran) for a younger mistress (Ludmilla Mikael), who then leaves him at the mercy of his failing business. Françoise (Michel Piccoli) is a materialistic doctor who’s sold out his humanitarian ideals for a fancy clinic and is stuck with a wife who is constantly cheating on him. Paul (Serge Reggiani) has succeeded at marriage but failed at writing. He earns his living as a journalist, but can’t finish his great novel. The three cling to one another for protection against a world they’ve never been able to master, and vent their frustration in sudden, raging arguments.

Triumphs: Like Robert, Sautet coaxes fine, unforced performances from his actors, especially Montand, who one moment puffs himself up with small triumphs, then ages twenty years when he’s hit with small defeats. Sautet’s point is typically French: it’s friendship, he suggests, that makes the difference between being merely unsuccessful in life and one of its real losers.

Neither Sautet nor Robert is going to set off any New Waves, but André Téchiné, the young director of “French Provincial,” might make a splash, once he settles on a style. In this story of the struggle of two women in the rise and fall of a small-town, factory-owning family, Téchiné has about ten styles going at once, ranging from Buñuel to Bertolucci. What’s interesting is his sense of something larger than the mere human interest of his plot, and he packs the movie with political metaphors of economic turning points in recent French history.

He also has Moreau at her best. As the town laundress and seamstress before World War II who marries into the decaying family and ends up running the works, Moreau is marvelous – tacky, majestic and real. She has seductively climbed out of so many beds in a black slip before that it’s also a welcome relief to see that this time her paunch is showing.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments