Original Publication: New West Magazine – July 17, 1978

“…Reading about Bruce Springsteen’s new album, I thought back—to the inside story of how he got the ‘Time’ and ‘Newsweek’ covers…”

Oh, no. Not again. I swallowed hard recently as I read my first review of Bruce Springsteen’s long-awaited new album, Darkness on the Edge of Town. The LP, wrote the Los Angeles Times’s respected rock critic, Robert Hilburn, “confirms what Springsteen’s earlier Born to Run album suggested. We finally have in the seventies a pure rock figure of the same Presley-to-Stones magnitude.” What’s the matter with Hilburn, I wondered. Doesn’t he like Bruce? Doesn’t he remember the brouhaha—mostly ha-ha—that followed Springsteen’s appearance on the covers of both Time and Newsweek the same week in ’75? I do. I wrote the Newsweek cover story.

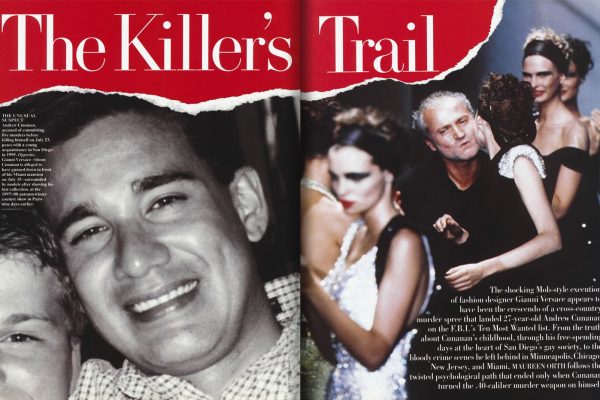

Most people would kill to be on the covers of both Newsweek and Time the same week, but for Bruce Springsteen it was just about the worst thing that could have happened to his career. Since then, since that first suggestion that he was a figure of “Presley-to-Stones magnitude,” it has been impossible for Springsteen to develop naturally. He constantly has to justify why such heavy media weight was thrown in his direction. After all, these two important publications usually reserve the right to copy each other only for events, booms and manias of impressive magnitude. But for a punk kid with a guitar—for just another nascent rock superstar?

The story of how Springsteen made the cover of Newsweek and Time the same week is, ironically, not so much about the hype as it is an example of the intense rivalry between the two magazines and their periodic desire to get their “hip” cards punched. In the summer of ’75, the New York “rock crit establishment,’ as the critics affectionately refer to themselves, discovered Springsteen. They “discovered” him when Columbia Records bough a quarter of the available tickets to his “debut” at a Greenwich Village nightclub, distributed them to nearly a thousand “tastemakers” and then spent $250,000 promoting his album, Born to Run. Ads for the LP featured, for the first time, comments from the rock critics, as if Springsteen were some movie or Broadway play. The rock critics hardly minded being billboarded. But as Springsteen’s stature rose, there were whispers and snickers—the word “hype” was in the air—especially because a few years earlier Columbia had tried to promote Springsteen as “the new Dylan.”

Newsweek, meanwhile, had just undergone sweeping editorial changes. People in new positions were anxious to prove they were tuned in. Let’s do something daring, they reasoned. Let’s put Bruce Springsteen on the cover while he’s still a boomlet instead of a full-fledged mania. “Have Bruce come by my place for drinks Saturday night,” one editor told me. “I’d like to see what he’s like.” I gently explained that rock stars rarely dropped by Riverside Drive for cocktails and that Springsteen would be performing that night on the New Jersey coast where he grew up. We finally decided to report the story as the making of a phenomenon—giving due, of course, to Springsteen’s potential talent.

“Boy, you guys really have balls for doing this,” said the astonished Columbia Records PR man. A Newsweek cover was beyond his most ambitious dreams.

The record business sorely needed Springsteen. The recession was on: record sales were off. The industry was desperately looking for one star to take off, to “define the seventies” and lead a sales revolution. Springsteen had a rebellious punk image, powerful lyrics and driving music. After I saw him in New Jersey, I decided Bruce was, along with Mick Jagger, the best live performer in rock ‘n’ roll. A few days later, however, a top editor summoned me. “Why are we doing this cover?” he asked. “My kid says Springsteen sucks.”

But for all his moves onstage, Springsteen had none of Jagger’s swagger offstage. He was a shy, confused kid saddled with an abrasive manager, and he was unsure of what to make of the sudden attention, particularly when, five days into my reporting, Time struck. Evidently someone from Time had learned that Newsweek was doing the cover. During the summer Time had published a glowing article on Springsteen. There were a number of genuine Springsteen freaks at Time—why should Newsweek have their baby? They convinced Time’s then managing editor Henry Grunwald—a highbrow more at home with Kissinger than Kiss—to give Springsteen the same prominence Newsweek was giving him, and in the same week. Eventually, Grunwald allegedly confessed that putting Springsteen on the cover was the biggest mistake of his career—a bold admission from a man whose publication supported the Vietnam was into the 1970s.

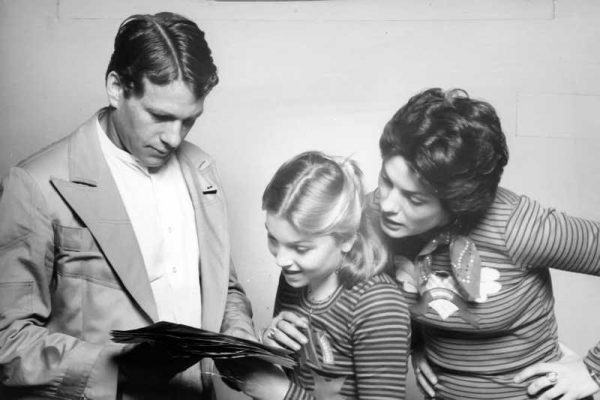

Even though some of its promo men supposedly got bonuses later for “delivering” the two covers, Columbia Records was staggered by Time’s decision. So was Springsteen. Poor Bruce. He was being probed and prodded by reporters. Disturbing information about decisions made by his manager, Mike Appel, was coming to light. Reporters even pursued his parents to their backyard in San Mateo.

A few days before my deadline, one of Bruce’s roadies drove me down to Asbury Park, where Bruce lived. I still needed to get a major interview from Bruce, the one that would tell me his real feelings about his life and his music. Although I was told it had all been arranged, nobody had told Bruce. He was surprised to see me at his doorway. He was packing for the road—throwing a few T-shirts into an old suitcase. He played Dion records for me; then we went to the boardwalk where the characters in his songs—the Magic Rat, Little Angel, Puerto Rican Jane—had originated. We played pinball. I won a plastic tarantula and teased him, telling him it was a perfect metaphone for what was going on. He excused himself to make a phone call and said he had to be in New York by nine that night. He offered to drive me there.

It was only when he was behind the wheel in the dark that Bruce relaxed. It was obvious that he had two great loves in his life—rock ‘n’ roll and cars. He told me how he’d clashed with his father while growing up and had had a sometimes painful, middle-class, Catholic upbringing. He said the first time he’d been able to look at himself in the mirror was the day he first strapped a guitar around his neck. He had been poor most of his life and didn’t feel comfortable with stardom. Tentatively, he asked what I thought about his being on both covers. It bothered him. We pulled up under a street light on Seventh Avenue. I said it wasn’t my place to interfere with his life, but since he’d asked…

I told him he was obviously not in control of his own career. Decisions were being made that he knew nothing about. It was clear from the questions he asked that he had no idea where his finances stood. He had no lawyer of his own—instead, his contract had been drawn up by Appel’s lawyer. I told him that either a Time cover or a Newsweek cover would be wonderful for him, but that both covers at one at this stage in his career would be death. I said he should choose one and that I hoped he chose Newsweek, because we were there first. I did not admit that I also hoped he chose Newsweek because the best fun in working there came when we beat Time on a story.

Bruce listened with an unhappy look on his face. He didn’t say much. At about eleven we said goodbye. I did not know that Bruce had driven to New York because he’d been expected at Time’s cover photo session at nine. Later that night I heard from a Columbia publicity man. After leaving me, Bruce had arrived, furious, at his office. A Time reporter had been waiting hours for Bruce at a nearby restaurant. Bruce tried to put his fist through a wall and refused to go. He was prevailed upon to go, however, and just a few short hours after Bruce Springsteen poured out his heart to me all the way up to New York from Asbury Park, he poured out his heart to Time all the way back down.

The Newsweek cover carried the billing, “The Making of a Rock Star,” but the original title we’d had, “The Selling of a Rock Star,” would have been better. In the lead of the story, I wrote, “Bruce Springsteen has been so heavily praised in the press and so tirelessly promoted by his record company, Columbia, that publicity about his publicity is a dominant issue in his career. And some people are asking whether Bruce Springsteen will be the biggest superstar or the biggest hype of the seventies.”

Soon after his appearance on both covers, Springsteen began to fade. In addition to the pressures brought on by the publicity, he demanded an accounting from Appel, charged him with fraud and dismissed him. Appel got an injunction which prevented Bruce from going into the studio to make another album. There were suits and countersuits, and I’d occasionally follow their progress in the music trades. “…In the period from 1972 through December 31, 1975,” ran one article, Springsteen alleged Laurel Canyon Productions Inc. “made $460,574.68 while Springsteen made $180,635.96 after recording costs were subtracted.” His legal battles with Appel sidelined Bruce for almost two years. A few weeks ago his new album finally arrived. Mindful of the problems hype had caused last time, Columbia sent no advance copies of the LP for review. In fact, Columbia almost seemed to sneak the record into stores.

I’m fond of Bruce and a big fan of his, but the new album disappointed me. Much simpler than Born to Run lyrically and more repetitive musically, it’s mostly about cars and adolescent fantasies, but without the rich characters he created before. On the new album, he sings:

You’re born with nothing

and better off that way

Soon as you got something they send

someone to take it away

I wanted the album to be amazing and wonderful—a giant leap forward—because if it were, of course, the Newsweek cover might not now seem so silly. But the only thing worse than what happened then would be to start the ballyhoo all over again. Bruce Springsteen doesn’t deserve it.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.