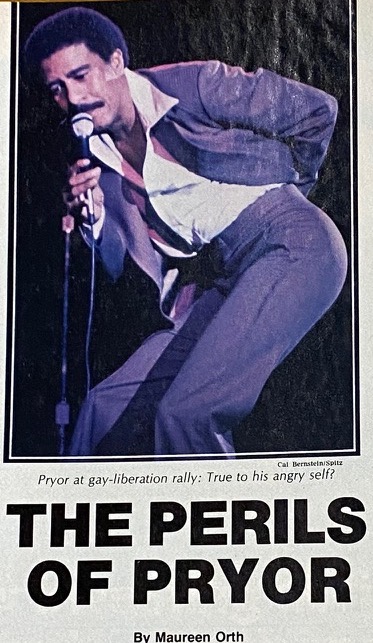

Original Publication: Newsweek – October 3, 1977

Richard Pryor can be funny: seven years ago during a nightclub act in Las Vegas, he stalked off the stage, shed all his clothes, walked stark naked into the casino, hopped on a table and yelled: “Blackjack!” Richard Pryor can be mean: last week at a benefit for the gay-liberation movement at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, Pryor launched into an attack on the predominantly gay white crowd of 17,000, lambasting them for “cruising” Hollywood Boulevard “when the niggers was burnin’ down Watts.” Then he bade them farewell: “Kiss my happy rich black ass.”

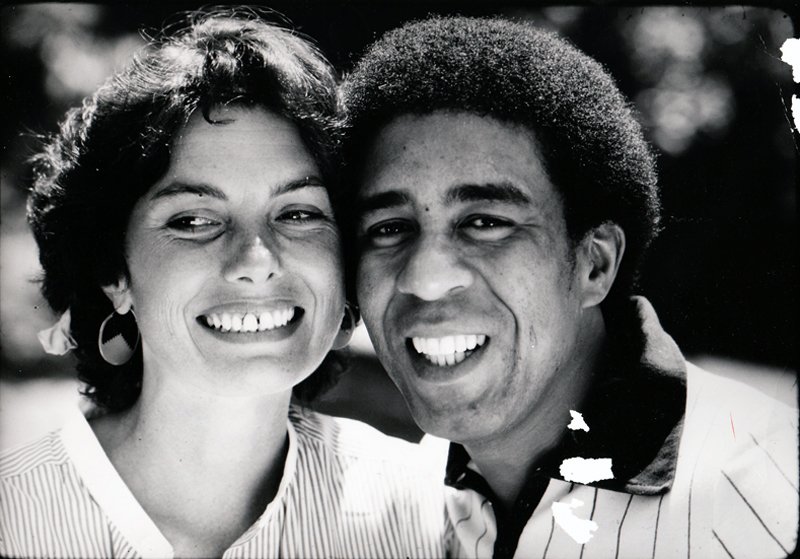

Richard Pryor can be surprising: last Thursday morning, Pryor, 36, got married for the third time (his bride was 25-year-old Deboragh McGuire) and then showed up at 10 a.m. to tape his TV show in his wedding suit. “I don’t care what anyone says,” declares Redd Foxx. “Richard Pryor is the funniest motherbleep around.” As Lily Tomlin, his co-star at the gay benefit, was quoted as saying last week: “When you hire Richard Pryor, you get Richard Pryor.”

Today, more and more of the country is getting Richard Pryor – in movies, on records and on television. Nonetheless, the question remains: can the hottest black comic around remain true to his angry self and make it as a superstar in mostly white America? Unlike the late Lenny Bruce, a comic of equal rage, Pryor lets his audience off the hook by satirizing both blacks and whites. But the millions who buy his comedy albums and go to his movies are still mainly blacks or hip young whites. Pryor’s outrageous, often scatological humor and his boyish charm have prompted two movie studios to sign him to long-term contracts and NBC to gamble on him as its great black hope, pitting him against Henry (the Fonz) Winkler in top-rated “Happy Days.” Typically, during the taping of the first show, Pryor did a skit wearing only fleshcolored tights. Later, the censors decided that was too much for the family hour and cut the skit.

Even so, “The Richard Pryor Show,” despite poor ratings for its first two outings, has become controversial. His hard-core fans think he’s gone soft; the uninitiated think he’s too tough. Pryor himself – aware that one of his old heroes, Bill Cosby, is now pitching the Ford Motor Co. on TV – is trying to figure out exactly where he is.

The purest distillation of what Pryor is all about is on his best-selling comedy albums, in which his humor is delivered by sharply drawn ghetto characters known to each other, but not to white outsiders, as Niggers. Here he is as a “Wino Dealing With Dracula”: “Say, nigger, you with the cape. What you doin’ peekin’ in them people’s window? What’s your name, boy? Dracula? What kind of name is that for a nigger? Where you from, fool? Transylvania?I know where it is, nigger. You ain’t the smartest motherf – – – in the world, even though you is the ugliest . . . Why don’t you get your teeth fixed, nigger – that shit hanging all out your mouth.”

In the eleven movies he’s been seen in to date, Pryor, a scene stealer, has not been nearly so flamboyant – or dirty – as he is on records. But the black screen image as defined by Pryor has traveled 180 degrees from that of the shufflin’ yes-ma’am Stepin Fetchit of 40 years ago. In “Silver Streak,” an otherwise forgettable thriller-comedy, he played a hip crook who masqueraded as a fawning waiter. First, he “accidentally” spilled hot coffee on the villain – for which the villian called him a “stupid, ignorant nigger.” Instantly, Pryor dropped the mask – and demanded: “What did you call me?”

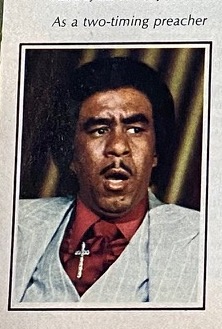

Since then, Pryor has lent his prickly presence to three more movies. In the financially successful “Greased Lightning,” he played the first champion black racing driver. In “Which Way Is Up?”, a soon-to-be released remake of Lina Wertmuller’s “The Seduction of Mimi,” he plays not just a grape picker who finds himself on the slippery ladder of success, but also the grape picker’s scabrous, patriarchal father and a two-timing preacher. In “Blue Collar,” a raw, political, uncomic film, he will appear as a beaten-down autoworker who sells out. He is set to film “The Wiz” – playing the Wiz himself. Ahead are roles opposite Lily Tomlin in the sequel to “The Sting” and with Bill Cosby in “California Suite.”

And now television. Behind “The Richard Pryor Show’s” poor ratings may be NBC’s decision to pit it against the Fonz. Or perhaps Pryor was overly ambitious in expecting to carry 60 minutes of elaborate comedy skits without the benefit of monologues or big-name guests. Perhaps it was the material itself, in which he cast himself in outlandish disguises, ranging from a swamp-fox evangelist with a Rastafarian wig to a rock singer in a group called Black Death who guns down his all-white audience – material that a San Francisco TV columnist labeled “black racist” and The Village Voice branded “sledge-hammer gag writing.” Whatever, the experience only confirmed what Pryor feared long beforehand.

‘I BIT OFF MORE THAN I CAN CHEW’

One night last summer, Pryor arrived at his comfortable home in the San Fernando Valley exhausted from filming all day. Waiting was a team of TV comedy writers. After a half hour of tossing around ideas for the first show, Pryor said: “I don’t feel this in my heart. It just stops here” (pointing to his head). More ideas were suggested. “Two years ago there was great shit on TV,” Pryor said. “Now people walk around without being outraged, numb from the shock.” Pause.

Then: “You know something? I don’t want to be on TV. I’m in a trap. I can’t do this – there ain’t no art.” Finally he burst into tears. “I’d rather you people know it than 50 million people. I bit off more than I can chew. I was turning into a greedy person. They give you so much money you can’t refuse.” But, pleaded a black woman writer, “You’ve got the chance to do something different on television.” “You want to see me with my brains blown out?” Pryor replied. “I’m gonna have to be ruthless here because of what it does to my life. I’m not stable enough. I don’t want to drink and I don’t want to snort and I can’t do it no other way.” For several days, the writers tried various ploys to get him to relent, including flying over his house in a plane with a banner that said, SURRENDER RICHARD. A few weeks later, Pryor agreed to do four shows, not ten as had been planned.

Pryor’s future all comes down to a big “if.” Paul Schrader, the director of “Blue Collar,” speaks for much of the show-business Establishment when he says: “Richard can do it all – comedy, romance, drama. He has a boysih quality that allows him to do or say almost anything and be forgiven. He can say things no other black man can get away with and a white audience will put up with it because his manner lessens the threat without diluting the message. Richard will be the biggest black star in history if he can keep the reins on himself or bit his tongue.” Says Pryor himself: “I’m not out to be cruel, but I’m not out to placate anyone either. I’m just trying to be Richard.”

Being Richard has never been easy. Much of his life has been sordid, but he has already survived most of the pressures that killed Lenny Bruce and Freddie Prinze. “I realized about two years ago,” he says, “that I was going to make it. I told God to save a place for me.” On his way, Pryor has shown a drive not to be bested by anyone. After Pam Grier, his former girlfriend and co-star in “Greased Lightning,” beat him for a second time at tennis, he wouldn’t speak to her for a day. She gave him some suggestions. “I’m supposed to take instructions and have you beat my ass too?” said Pryor. “No way.” Instead, he challenged her to game after game. Once, when she fainted in the middle of a match, he got so mad that he stormed off the court.

THE BACKSIDE OF LIFE

Pryor’s whole stance toward women is somewhere between sassy sexist and mild misogynist. He wants to co-star with Cybill Shepherd in a remake of Lina Wertmuller’s “Sweep Away,” in which an uppity blond bourgeois lady gets marooned on an island and slapped around by a dark proletarian man whom she finally begs to ravish her. “I liked it because it’s cruel,” says Pryor, “and that’s sexy.” His attitude was probably formed early.

Pryor grew up in a whorehouse and bar in Peoria, Illinois. Both his parents worked there and the proprietress of the place was his grandmother. The neighborhood was rich in what Pryor calls “the sporting life,” full of colorful characters – hustlers, pimps, numbers men – who have since popped out in his repertoire. Mudbone, Pryor’s celebrated old storyteller of insane tales, was actually an old wino who’d come to visit the family. Although he doesn’t like to read, Pryor has a perfect aural memory – he can mimic anyone, and he says that halt the dialogue he uses was once actually spoken to him. “My grandmother told me,” he says, “Don’t you put me on no more of those records. You know I don’t talk like that!’ I say, ‘Grandma, you forgot.” Early on, Pryor found that being honest and being funny were almost the same thing.

“These people lived the backside of life,” says Pryor, “and they saw things different than if you had money and were careful what you said. My father was devastatingly funny and would tell the truth even if people didn’t want to hear it. To a lot of people it might shock. But the words are true. It’s a language within a language that’s so to the point it makes pictures in your mind.”

Despite his environment, Pryor says he was brouht up strictly. He had to go to chuch and had “to obey.” His mother took off at an ealy age, and Pryor, who is shy, softspoken and moody, spent a lot of time alone, talking to an imaginary friend named Charlie Eggy. “My mother went through a lot of hell behind me,” says Pryor, “because people would tell her, ‘You don’t take care of that boy.’ She always wanted me to be somebody and she wasn’t the strongest person in the world. But I give her a lot of credit. At least she didn’t flush me down the toilet like some do. I’m not trying to be crude but I found a baby in a shoe box once when I was a kid – dead.”

DOING TARZAN YELLS

Despite good marks, Pryor got kicked out of a Catholic grade school because the nuns found out where he lived. He was next, inexplicably, put into a class for retarded children in the public school (by then, he had discovered he could attract attention by doing Tarzan yells). At 14, he left school for good after punching out a science teacher. “I remember I used to paste my name over Marlon Brando’s name on picture of movie marquees, “Pryor says. “I wanted to be the funniest person in the world.” In the Army, where he again got in trouble fighting, he performed in variety shows and, when he got out, began working as an emcee in local clubs around Peoria, getting his jokes out of a joke book.

In 1963, he headed for New York and the little clubs of Greenwich Village.”It was a time,” recalls screenwriter Buck Henry, who was there, “when every doorway late at night had someone standing in it who would later be famous” – including Bill Cosby, Pryor’s idol. By the time Pryor landed guest slots on the Ed Sullivan and Mery Griffin shows, he was copying Cosby’s style and leaving his own behind.

Eventually, he couldn’t stand the pressure of trying to be something he wasn’t. During the late ’60s, he failed to file his income tax, for which he later served time. He got heavily involved in drugs; people were suing him right and left for broken contracts; he was charged with beating up a hotel clerk and one of his ex-wives – and settled both cases out of court. (Pryor first became a father as a teenager and has four children by four women – two black, two white.) In 1969, trying to do his “real” material, he bombed with a group of black deejays who objected to him saying “nigger.” Finally, in 1970 he began having what he calls “a walking nervous breakdown” (it lasted for two years and he accumulated debts of $600,000). He walked off the Aladdin Hotel stage in Las Vegas, fed up with doing “white bread” humor, and settled in Berkeley, Calif.

“I got myself a little apartment,” says Pryor, ” and bought Marvin Gaye’s record, ‘What’s Going on’ and played it over and over and I read some of Malcolm X’s speeches and thought, hey, there’s someone who thinks like I do. I’m not crazy.” Pryor’s work at Berkeley clubs was experimental. Some nights he’d deliver a successful routine just by using pure sounds or repeating a word like “bitch” with a dozen different intonations. But Pryor really liked Berkeley because it was easy to get cocaine there. “I’m a highly dramatic person,” he says. “I’d take the dope and pretend I was Miles Davis. But I couldn’t heve been a junkie because when I wanted to stop [which he did last year] I stopped on a dime.”

Pryor’s big break came in 1972, when he was cast as Diana Ross’s accompanist in “Lady Sings the Blues.” He was then a writer on Mel Brook’s hit film “Blazing Saddles.” His second big break was meeting his lawyer, David Franklin, in 1975. A powerful black political figure in Atlanta – he advises Andrew Young and master-minded Mayor Maynard Jackson’s campaign – Franklin handles some of the biggest black names in show business. He quickly straightened out Pryor’s affairs. “Ninety percent of the black artists are getting ripped off today,” Franklin says. “The best service I could give them would be to take a machine gun and wipe out all the people around them and start over.” Franklin also saw to it that Pryor kept his nose clean. “I told him,” he says, “that I wasn’t interested in representing in junkie.”

Some people worry that Pryor, whose financial generosity to his family and friends is lavish, may be tying himself up to too many deals too fast. “There’s a desperate quality to some of the choices he makes,” says Steve Krantz, producer of “Which Way Is Up?” “It’s not for the money, it’s his lack of self-confidence.”

‘I NEED TIME TO JUST GO BLANK’

Which brings Pryor right back to his own dilemma. “Sometimes what appears to be real in my life isn’t – I’m still acting,” he says. “Having Deborah in my life is real and I never thought I’d have that, and being in my home is real – that’s all I’ve got in my life that’s real. I find myself talking to people I don’t know, shaking hands with them. A lot of people seem to be closing in on me. I don’t want to sign autographs, but I don’t want to hurt their feelings. Now I want change my name. Richard Pryor is this actor person, and I need time to just go blank. I’m thinking of moving to farm in Oregon. I only want to do projects where I know what I’ve gone through to get there.”

One such project was his role as the sellout autoworker in the upcoming “Blue Collar.” “It changed my life,” says Pryor. “I had a whole struggle going on – getting that deep, revealing that pain. It’s scary. People are going to come in expecting laughs and they’ll see this different side. I don’t want to be used to bring in the black audience and then to have them devastated. They have to be prepared. I don’t think I could stand the rejection.”

Richard Pryor gives off an aura of danger: it’s both his sword and shield. Most people who know him are afraid of him. At the heart of his humor is an explosive unpredictability. But there’s nothing unpredictable about where he’s coming from. “I often have this dream,” he says. “I’m in a beautiful grassy field surrounded by beautiful people and in the middle is an airplane. It’s going to heaven, talking all the people there. I’m there too and I begin to look around and realize all the people are very pretty but they’re white. So I decide, I don’t want to go to heaven if there’s not gonna be no niggers there.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments