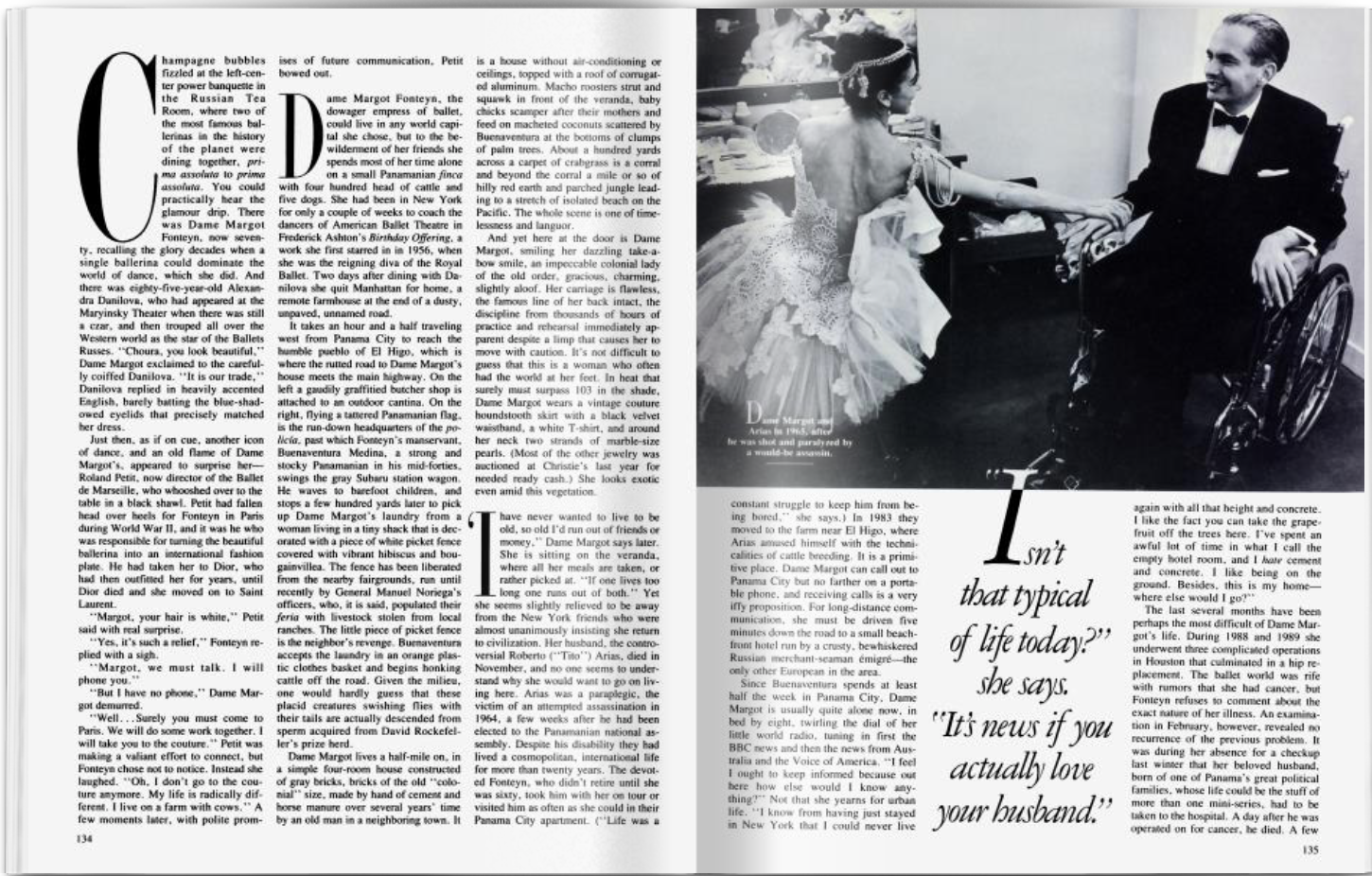

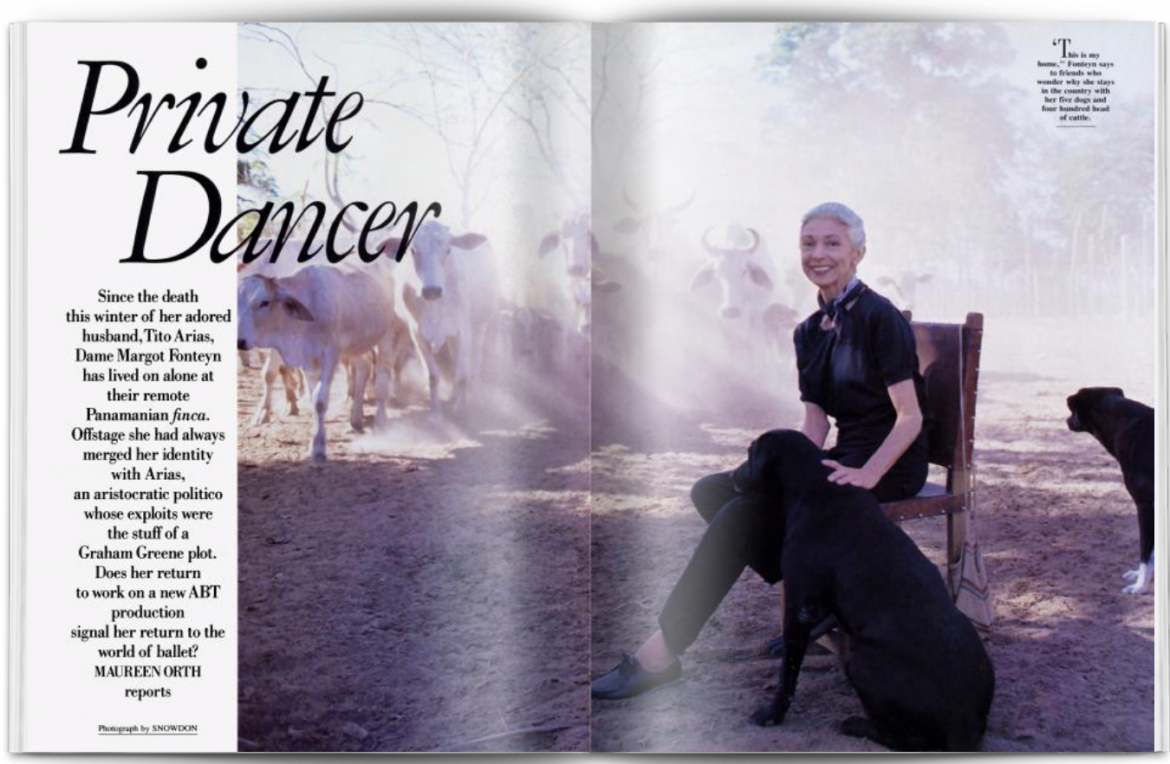

Since the death this winter of her adored husband, Tito Arias, Dame Margot Fonteyn has lived on alone at their remote Panamanian finca. Offstage she had always merged her identity with Arias, an aristocratic politico whose exploits were the stuff of a Graham Greene plot. Does her return to work on a new ABT production signal her return to the world of ballet?

Champagne bubbles fizzled at the left-center power banquette in the Russian Tea Room, where two of the most famous ballerinas in the history of the planet were dining together, prima assolutato prima assoluta. You could practically hear the glamour drip. There was Dame Margot Fonteyn, now seventy, recalling the glory decades when a single ballerina could dominate the world of dance, which she did. And there was eighty-five-year-old Alexandra Danilova, who had appeared at the Maryinsky Theater when there was still a czar, and then trouped all over the Western world as the star of the Ballets Russes. “Choura, you look beautiful,” Dame Margot exclaimed to the carefully coiffed Danilova. “It is our trade,” Danilova replied in heavily accented English, barely batting the blue-shadowed eyelids that precisely matched her dress.

Just then, as if on cue, another icon of dance, and an old flame of Dame Margot’s, appeared to surprise her— Roland Petit, now director of the Ballet de Marseille, who whooshed over to the table in a black shawl. Petit had fallen head over heels for Fonteyn in Paris during World War II, and it was he who was responsible for turning the beautiful ballerina into an international fashion plate. He had taken her to Dior, who had then outfitted her for years, until Dior died and she moved on to Saint Laurent.

“Margot, your hair is white,” Petit said with real surprise.

“Yes, it’s such a relief,” Fonteyn replied with a sigh.

“Margot, we must talk. I will phone you.”

“But I have no phone,” Dame Margot demurred.

“Well.. .Surely you must come to Paris. We will do some work together. I will take you to the couture.” Petit was making a valiant effort to connect, but Fonteyn chose not to notice. Instead she laughed. “Oh, I don’t go to the couture anymore. My life is radically different. I live on a farm with cows.” A few moments later, with polite promises of future communication, Petit bowed out.

Dame Margot Fonteyn, the dowager empress of ballet, could live in any world capital she chose, but to the bewilderment of her friends she spends most of her time alone on a small Panamanian finca with four hundred head of cattle and five dogs. She had been in New York for only a couple of weeks to coach the dancers of American Ballet Theatre in Frederick Ashton’s Birthday Offering, a work she first starred in in 1956, when she was the reigning diva of the Royal Ballet. Two days after dining with Danilova she quit Manhattan for home, a remote farmhouse at the end of a dusty, unpaved, unnamed road.

It takes an hour and a half traveling west from Panama City to reach the humble pueblo of El Higo, which is where the rutted road to Dame Margot’s house meets the main highway. On the left a gaudily graffitied butcher shop is attached to an outdoor cantina. On the right, flying a tattered Panamanian flag, is the run-down headquarters of the policia, past which Fonteyn’s manservant, Buenaventura Medina, a strong and stocky Panamanian in his mid-forties, swings the gray Subaru station wagon. He waves to barefoot children, and stops a few hundred yards later to pick up Dame Margot’s laundry from a woman living in a tiny shack that is decorated with a piece of white picket fence covered with vibrant hibiscus and bougainvillea. The fence has been liberated from the nearby fairgrounds, run until recently by General Manuel Noriega’s officers, who, it is said, populated their feria with livestock stolen from local ranches. The little piece of picket fence is the neighbor’s revenge. Buenaventura accepts the laundry in an orange plastic clothes basket and begins honking cattle off the road. Given the milieu, one would hardly guess that these placid creatures swishing flies with their tails are actually descended from sperm acquired from David Rockefeller’s prize herd.

.

Dame Margot lives a half-mile on, in a simple four-room house constructed of gray bricks, bricks of the old “colonial” size, made by hand of cement and horse manure over several years’ time by an old man in a neighboring town. It is a house without air-conditioning or ceilings, topped with a roof of corrugated aluminum. Macho roosters strut and squawk in front of the veranda, baby chicks scamper after their mothers and feed on macheted coconuts scattered by Buenaventura at the bottoms of clumps of palm trees. About a hundred yards across a carpet of crabgrass is a corral and beyond the corral a mile or so of hilly red earth and parched jungle leading to a stretch of isolated beach on the Pacific. The whole scene is one of timelessness and languor.

And yet here at the door is Dame Margot, smiling her dazzling take-a-bow smile, an impeccable colonial lady of the old order, gracious, charming, slightly aloof. Her carriage is flawless, the famous line of her back intact, the discipline from thousands of hours of practice and rehearsal immediately apparent despite a limp that causes her to move with caution. It’s not difficult to guess that this is a woman who often had the world at her feet. In heat that surely must surpass 103 in the shade, Dame Margot wears a vintage couture houndstooth skirt with a black velvet waistband, a white T-shirt, and around her neck two strands of marble-size pearls. (Most of the other jewelry was auctioned at Christie’s last year for needed ready cash.) She looks exotic even amid this vegetation.

‘I have never wanted to live to be old, so old I’d run out of friends or money,” Dame Margot says later. She is sitting on the veranda, where all her meals are taken, or rather picked at. “If one lives too long one runs out of both.” Yet she seems slightly relieved to be away from the New York friends who were almost unanimously insisting she return to civilization. Her husband, the controversial Roberto (“Tito”) Arias, died in November, and no one seems to understand why she would want to go on living here. Arias was a paraplegic, the victim of an attempted assassination in 1964, a few weeks after he had been elected to the Panamanian national assembly. Despite his disability they had lived a cosmopolitan, international life for more than twenty years. The devoted Fonteyn, who didn’t retire until she was sixty, took him with her on tour or visited him as often as she could in their Panama City apartment. (“Life was a constant struggle to keep him from being bored,” she says.) In 1983 they moved to the farm near El Higo, where Arias amused himself with the technicalities of cattle breeding. It is a primitive place. Dame Margot can call out to Panama City but no farther on a portable phone, and receiving calls is a very iffy proposition. For long-distance communication, she must be driven five minutes down the road to a small beachfront hotel run by a crusty, bewhiskered Russian merchant-seaman emigre—the only other European in the area.

Since Buenaventura spends at least half the week in Panama City, Dame Margot is usually quite alone now, in bed by eight, twirling the dial of her little world radio, tuning in first the BBC news and then the news from Australia and the Voice of America. “I feel I ought to keep informed because out here how else would I know anything?” Not that she yearns for urban life. “I know from having just stayed in New York that I could never live again with all that height and concrete. I like the fact you can take the grapefruit off the trees here. I’ve spent an awful lot of time in what I call the empty hotel room, and I hate cement and concrete. I like being on the ground. Besides, this is my home— where else would I go?”

The last several months have been perhaps the most difficult of Dame Margot’s life. During 1988 and 1989 she underwent three complicated operations in Houston that culminated in a hip replacement. The ballet world was rife with rumors that she had cancer, but Fonteyn refuses to comment about the exact nature of her illness. An examination in February, however, revealed no recurrence of the previous problem. It was during her absence for a checkup last winter that her beloved husband, born of one of Panama’s great political families, whose life could be the stuff of more than one mini-series, had to be taken to the hospital. A day after he was operated on for cancer, he died. A few weeks later the U.S. invaded Panama and Dame Margot was isolated on the farm with a Filipino houseguest who read her Bible stories while U.S. jets flew overhead. From her beach one can see the island where General Noriega had a house, one of the places, locals claim, where he kept his Brazilian witches.

“Isn’t that typical of life today?” she says. “It’s news if you actually love your husband.”

Fonteyn and her husband had known Noriega for years. Just last summer Arias, who was both the son and nephew of former Panamanian presidents, scandalized his family by running for national deputy as the candidate of a party sympathetic to Noriega. He lost badly. Today, Dame Margot downplays the relationship, dismissing her husband’s candidacy as just another attempt to avoid boredom. Of the general she says, “You can be clever without being wise. I think General Noriega was clever but not wise.”

Fonteyn has been involved in Panamanian political life for decades, if only as an interested observer. “She knows a tremendous amount,” says former U.S. ambassador to Panama Ambler Moss. In the years after her husband was shot she was literally his voice. His paralysis prevented him from speaking above a faint whisper that was barely understood except by Fonteyn and Buenaventura, and she “translated” his words for friends and colleagues.

“Even after he was shot, in a wheelchair and barely intelligible, people still consulted him about politics,” says Moss. “It was an interesting role—a kind of political guru.” And Fonteyn made it possible for him to function—taking care of him, speaking for him. “He had a wonderful brain,” she says now. “I can’t tell you what he would have had to say about recent events in Panama.”

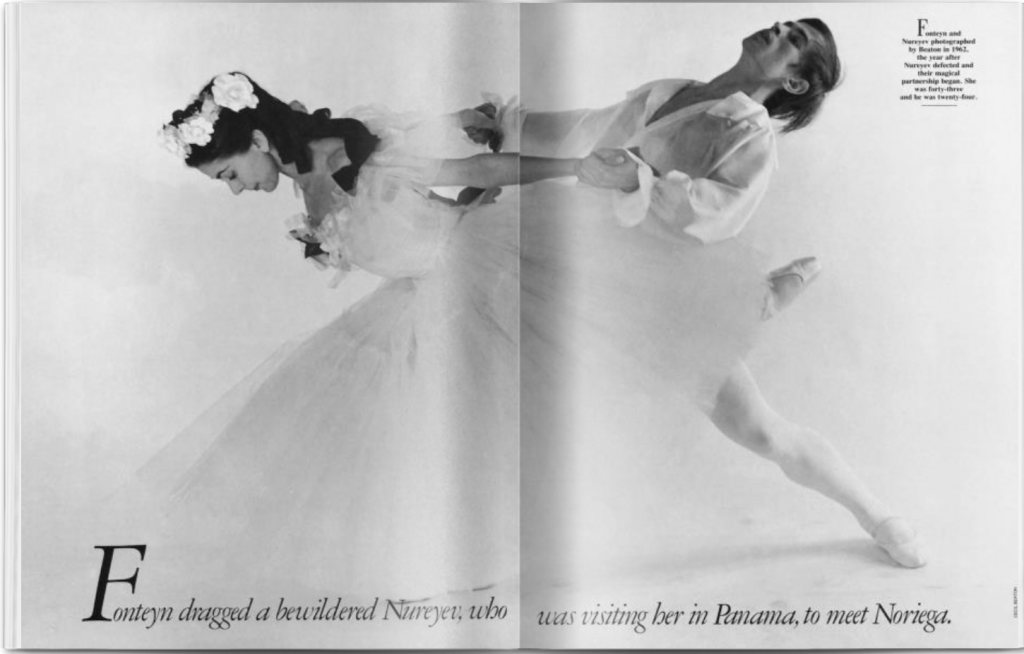

Fonteyn dragged a bewildered Nureyev, who was visiting her in Panama, to meet Noriega.

Years before Noriega ascended to the presidency, but when he in fact controlled much of the country as the head of the intelligence services, he would often lunch or dine with Arias and Fonteyn. “Noriega was the kind of person who wanted to feel important,” Buenaventura explains. “He knew Margot and Tito were very important, so he wanted to know them, to be close to them.” “Noriega was fascinated with Margot’s fame,” says Louis Martinz, one of Fonteyn’s closest friends and now the international media spokesman for the new Endara government. “But when she retired, he lost interest.” Even so, Noriega threw a showy birthday party for her in 1983, with a two-tiered cake featuring reclining porcelain ballerinas on a bed of bright-green shredded coconut. He was too shy to dance Panamanian folk dances with her, so Louis Martinz did. And in 1987 Dame Margot dragged a bewildered Rudolf Nureyev, who was visiting her in Panama, to meet the general. “At least Noriega gave the impression that he knew such things as art existed,” she says now, although she is not a defender. “Nine times out of ten, foreign invasions are not justified, but this time I think the U.S. did the right thing. There was no other way.”

“Her stubbornness in light of reality is immense, but it is also her strength.”

“The sweetest sound I ever heard was that of the American bombers,” says Gerasimos Kanelopulos, a friend of Dame Margot’s and the owner of the Argosy, a lively Spanish-English bookstore in Panama City. Kanelopulos and a few other friends, including Louis Martinz, have come to Saturday lunch. “Look, did you ever see that old TV show, The Twilight Zone?” Martinz asks. “Well, that’s Panama—the twilight zone.” Martinz was an admirer of Roberto Arias’s uncle, the charismatic and eccentric Amulfo Arias, who was three times elected to the Panamanian presidency and three times deposed, with American approval. He recalls that Arnulfo—a Rosicrucian who followed the stars and spoke of a philosophy of concentric circles—had a certain affinity with Noriega, who would at times give incomprehensible speeches about interlocking triangles.

As the lazy lunch of unintentionally organic beef, fish, rice with coconut and tropical vegetables turns into an eight-hour affair—washed down with pitchers of Buenaventura’s icy sangria—Fonteyn and her friends trade the latest firsthand anecdotes about Noriega, the new government, the state of the canal, Dan Quayle, and the U.S. Southern Command. The consensus of this well-informed group is that Noriega never thought the U.S. would come after him. He had lost touch with reality by mixing too many religions—”Catholic and Buddhist and his Brazilian voodoo.” Basically he was caught because he couldn’t get his mojos working right.

But so what? Let the gringos worry about Noriega. “He is not a priority in our minds now,” declares Dame Margot’s stepson, Roberto junior. “This is a country of hear no evil, see no evil,” his ex-wife, Elba, adds. This is Panama, after all, a poor land settled by pirates whose progeny became bankers, a country that has few important exports, a country that before Noriega wrecked the economy had gained what strength it had—apart from the canal—by being a safe haven for drug money.

“If you try to find a clean business in Panama it doesn’t exist,” a former C.I.A. chief there says cynically. “Even the extreme left and the Communists drive around in Mercedes and BMWs. Noriega would be there today if he hadn’t gotten greedy and gone into the drug trade and gotten the U.S. on his back.” Could such a harsh judgment be accurate? When Dame Margot’s friends are told that a recent book on Noriega suggests that to the dictator—as well as to many Panamanians—being useful was valued more highly than being loyal, they agree that this is a “great insight.”

Margot Fonteyn first saw Panama in 1955, shortly after she married Roberto Arias. They had met eighteen years earlier, when she was a hardworking teenage ballerina with the small Sadler’s Wells ballet. Each May the company went to Cambridge to perform at the theater that John Maynard Keynes had built for his dancer wife, Lydia Lopokova. Tito was a Cambridge undergraduate, the son of Harmodio Arias, a brilliant Panamanian lawyer and self-made man who himself had been educated at Cambridge on a special scholarship the Panamanian congress made possible for poor boys from the provinces, and had gone on to serve as president of his country.

Fonteyn, who began life with the ordinary English name of Peggy Hookham, was the reserved daughter of a British father and a half-Brazilian mother. She spent her first eight years in England and then sailed from the U.S. to Shanghai, where her father was employed as the chief engineer of the British Cigarette Company. By the time she was fourteen and enamored of the dance, Peggy Hookham had left school, and she and her mother returned to England to learn once and for all if she should seriously pursue ballet. After ten minutes of auditioning in her bare feet she was accepted by the director of the Vic-Wells (later called the Sadler’s Wells, and then the Royal Ballet), Ninette de Valois. She was only fifteen when she was made a full member of the company, and seventeen when she danced Giselle. By then Margot Fonteyn (her stage name taken from her mother’s maiden name—Fontes) was a star, with an extraordinary onstage aura that mesmerized audiences. “I realized,” said her first partner, Robert Helpmann, that “she had the curious quality of making one want to cry.”

The morning after she met Roberto Arias, Fonteyn herself was in tears. “I got up and I walked across the room and I had this really strange sensation. So I went back and sat on the edge of the bed. Then somehow it came into my mind about people walking on air when they’re in love. Not till then did I remember this person I had seen the night before. And then I said, ‘Oh, that must be it.’ “

And that was it for many years. The mysterious and reticent Tito sailed for Panama for summer vacation and out of her life. There were other loves, of course. Margot Fonteyn was always awash in roses. She knew practically every major celebrity in Britain—there were sailing parties with Olivier, dinners with David Niven. “I have a side to me that likes to party and dance all night,” she says. And yet she worried about becoming “an old ballerina,” ready for retirement at age thirty-five with no place to go and no one to love.

Incredibly, she felt this way even in 1949, when she and the Sadler’s Wells company visited New York and took the town by storm. Curtain calls took twenty minutes. The parties were nonstop. Their tour set box-office records and Margot Fonteyn made the cover of Time. The following year she made the cover of Newsweek. New York was Fonteyn’s turning point. “I think I won New York by smiling,” she once said, and America, suddenly dance-hungry, was smitten. The U.S. made her ballet’s biggest star. “She lit up the stage,” says Robert Gottlieb, who saw those first performances in New York and many years later edited her autobiography and her book The Magic of Dance. “Her curtain calls alone made your heart jump.”

It was during a New York season in the early fifties that Roberto Arias reappeared, without warning. He had just been named Panama’s ambassador to the U.N., and one night he came to the theater where Fonteyn was performing. The next morning she was awakened by a phone call saying he was coming by for breakfast. Over coffee, Dame Margot recalls, he said, ” ‘You’re going to marry me and be very happy.’ And I said, ‘You’re crazy.’ ” He was then married to someone else, with three children under the age of seven. A few minutes later he took off for the airport.

A hundred roses were delivered to her hotel by his chauffeur. There was a diamond bracelet and a fur coat that was too big. His limo was at her disposal. Since they had last seen each other, Arias had woven a rich tapestry of powerful international contacts. While still in school he had quite by chance been responsible for getting F.D.R.’s mother, Mrs. Sara Delano Roosevelt, out of Paris before war was declared in Europe and had thus earned the gratitude of the entire Roosevelt clan. He had become a maritime lawyer for Aristotle Onassis, and also the owner of a tabloid newspaper, La Hora. In La Hora, he gave the Panamanian upper class the nickname they are still known by: rabiblancos, or “white butts,” taken from the name of a white-tailed Panamanian bird.

“They were a very political family,” sniffs a Panamanian matron when asked about the Ariases. “They were always running for office or trying to get power. That was their thing.” “Tito is the reflection of an era,” says another Panamanian, “when the traditional oligarchy ran the country.” But he seems to have also been something of a rogue. “He got away with murder all his life—there was business he was doing that was not very straight,” says his sister, Rosaria Arias de Galindo, the publisher of the Panama City daily Panama America. She thinks that people protected him out of respect for their father.

“When you talk about Tito Arias you have to talk about Churchill—he was a close friend of Churchill’s. When he’d go to the States he’d be with these senators and movie stars—John Wayne, Elizabeth Taylor,” says his cousin, Panamanian national deputy Lucas Zarak. “In the entire world there are few people who had as many good connections.” Lucas Zarak, who is a nephew of Arnulfo Arias’s wife, thinks that “Tito tried to be a little bit of everything in his life—a little bit of a playboy, a little bit of a smuggler. He liked that people talked about him—it didn’t matter how.” Zarak remembers the time—shortly before he was shot—when Arias was campaigning for deputy and in an elevator by chance ran into a political opponent who was also a friend. “Tito asked him how it was going and the man said not so good because he was running out of money. So Tito reached into his pocket and counted out $5,000 and gave it to him. Even when he was a little boy he was always in trouble because he spent more than his allowance.”

“They literally broke the mold when they made Tito,” says Louis Martinz. “When people would gossip about him I’d say, Stop it. Stop comparing him to a human being. Pretend he’s from Mars. The same standards don’t apply to him.”

But he was, in any case, definitely the man for Margot Fonteyn.

“This was the only person I felt I could be married to. I thought, The only way I will always have an interesting life is with this man—it certainly won’t be boring,” she says. On February 5, 1955, they were married in a chaotic civil ceremony in Paris and then honeymooned on a yacht in the Bahamas.

Arias soon became Panama’s ambassador to Great Britain, and Fonteyn, elevated to a Dame of the British Empire, eagerly began the rounds of the diplomatic life. In January of 1959 the Ariases made a private visit to Cuba, where Castro had just come to power. A few weeks later, the couple “went fishing” together off the coast of Panama to meet up with a waterskiing skiff that was sinking because of the arms it was filled with. Arias had begun a revolution that couldn’t shoot straight. What followed was a debacle featuring a band of Cubans—led by a nightclub owner—landing at the wrong time in the wrong place, Arias and Fonteyn being separated on two different boats, gunfire that caused the death of one of Arias’s compadres, and Arias’s eventual escape to the Brazilian Embassy—but not before he left behind a briefcase. In the next few days the Panamanian press had a field day with the news that documents in the briefcase showed that in addition to the help from his left-wing Cuban friends Arias had received $682,850 from John Wayne for a “shrimp business.” Dame Margot ended up spending a night in a Panamanian jail, in a V.I.P. cell decorated with roses grown by the warden. At the time, Life magazine labeled the insurrection “one of the funnier fiascos of recent history.”

Fonteyn remains mum on the subject of her husband’s political and business deals, and it’s clear that the Arias family has always tried to protect her, even though they often took a dim view of his activities. Lucas Zarak recalls, for instance, that Arias was arrested twice for bootlegging. “You know, when you get right down to business with those political things and revolution. . . with Tito they were all very stupid—they were so impractical,” says his sister. “But I remember my father telling me once—when I went to see Margot, who was dancing in Chile—’No matter what you tell her, remember she is his wife.’ I always had the impression that the relationship between man and wife had absolutely nothing to do with the relations a man and woman can have with the rest of the world.”

Not long after the abortive coup, Arias was back as the British ambassador, under a different Panamanian president. There were weekend visits to Churchill at Chartwell, where Viscount Montgomery jokingly offered his services for Arias’s “next revolution.” Or they’d dash down to Monte Carlo for trips on Onassis’s yacht, where Arias had a brass plaque with his name outside his own private stateroom. When he couldn’t bear the gloom of the English climate, he’d bolt suddenly for Panama. On one of these visits he showed up at a fancy party wearing a white linen Panama suit after they had gone out of fashion. When asked why, he replied, “Because I’m the white sheep of the family.” Such sallies delighted Dame Margot, who remembers him also as the “most charitable man imaginable. He once got a telegram from an old lady friend that said, ‘Darling Tito, could you please wire me $300. I’ve got a banker on the hook and if I can have three new dresses, I think I can snag him.’ He wired the money immediately.”

Roberto Arias was shot five times in June of 1964. The assailant was a close aide who thought he had been double-crossed politically. At the time of the murder attempt, Margot Fonteyn was dancing at the Bath Festival in England. She was forty-five, and two years into her historic partnership with Rudolf Nureyev, who was still in his twenties. He had defected in 1961 and their magical stage relationship had developed almost immediately. Nureyev and Fonteyn were rumored to be carrying on offstage as well (rumors she always denied), and there were also rumors that the Arias marriage was on the rocks and that Arias had a roving eye. But some of their friends dispute these claims. “He did spend all her money and she did have problems with him,” says Queenie Altamorano, who would often visit Arias when Fonteyn was away, “but she’s a very devoted human being and she doesn’t change her mind easily. Her life was Tito.”

Her professional life was Nureyev. “At first I didn’t want to dance with him. It was a big challenge because I was so much older,” she remembers now. “Then everyone said this gave me renewed life and everything. Probably it did—I don’t know. After we did the first performance and it was such a tremendous success, I thought it would be sensible to retire, on that high point. But somehow or other, fate doesn’t always do the things that might be sensible. Fate leads you to do other things. And I’m a great fatalist.”

Driven by the necessity of caring for her husband, Fonteyn, who never earned any sort of big money until she danced with Nureyev, maintained a killer schedule, flying back and forth to Panama for a few days from halfway across the world. The ballerina who had planned to stop performing at thirty-five danced for twenty-five years beyond that.

Like most Panamanians, Rosaria Arias de Galindo, her sister-in-law, reveres Margot Fonteyn. She is thought of as something close to a saint for her dedication to her difficult and restless husband, who, despite his infirmity, would think nothing of deciding to go abroad from one day to the next, changing countries at whim, usually needing a ticket for Buenaventura as well as other expensive care. Margot Fonteyn paid all the bills with nary a word of complaint. “One day we found out she had pneumonia,” says Arias de Galindo. “She refused to stay in the hospital, so she came here. She was thrilled to be wearing one of my nightgowns. She herself could never undress at night because Buenaventura or someone had to come into the bedroom two or three times a night to turn Tito. Something so human as being naked underneath a nightgown she could never experience.” Señora Galindo shakes her head in disbelief.

Once, in order to attend a New York party at a penthouse, Arias had himself hoisted up the fire escape in his wheelchair. “He was always very macho,” says one of Fonteyn’s closest friends in New York, publicist and balletomane Donald Smith. “He would just continue doing what he wanted to do. If he decided he wanted to go swimming, a car would have to be hired for the afternoon to take him to the New York Athletic Club around the comer. Then someone would have to be hired to help put him in the pool. An afternoon could end up costing $600 or $700.”

“He was an extremely strong, opinionated man—she really did play the role of the acquiescent wife to a very, very great extent,” says American Ballet Theatre co-director Jane Hermann. “Tito made the decisions.” “She would be ravenous after a performance, but she would always cut Tito’s food first and feed him first,” says Louis Martinz. “She had no identity of her own when Tito was around.” Yet Donald Smith recalls the look of utter amazement on Dame Margot’s face when he blurted out one day how sorry he was for her—”you whose whole life is motion being tied up with someone who can’t move.” “Oh, Donald,” Dame Margot replied, “it’s so much harder for you. You see, I love him.”

“Her stubbornness and loyalty in light of reality is immense,” says an old friend, “but it is also her strength.” Fonteyn says she doesn’t understand why people are surprised that “I took my wedding vows seriously—for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health. Isn’t that typical of life today? It’s news if you actually love your husband.” In her autobiography, published in 1976, there is a passage that perhaps helps explain her attachment to Arias. “Real life often seemed so much more unreal than the stage; or maybe I should say my identity was clear to me only when I assumed some make-believe character,” she writes. “It was so easy for me to step out into the limelight through the plywood door of Giselle’s cottage and suffer her shyness, ecstasy, deception, and madness as if it was my own life catching me by surprise at each new turn…. But when I left the stage door and sought my orientation among real people, I was in a wilderness of unpredictables in an unchoreographed world.” On the recent documentary of her life broadcast on PBS, she confessed that in fact her identity came from Arias. “Until I married Tito I had absolutely no idea who I was offstage. And then I married him and I knew—I was Mrs. Tito de Arias.”

“Come on, Merengue darling. Come, my little boy….I love you so much.” Fonteyn’s big Labradors are the center of attention on the ranch now. Four dog beds were the only furniture on the veranda for a long time, and were often mistaken for chairs by visitors who tried to sit in them. There is a fifth dog, but she almost never associates with the other four, since she sleeps with the mistress. She used to sleep with Arias, but since his death has switched beds. “I once asked my husband, ‘Who shall I take care of when you’re gone?’ ” Dame Margot says. “My husband loved the dogs very much. They kept him company. If I left here, who would take care of my dogs?”

The wound of Arias’s death is still very fresh. “You know, I was just happy being with him—it didn’t matter what he was doing or where he was.” After lunch, while guests are still seated at the table under the thatched ramada, Dame Margot is briefly in tears up on the veranda with her friend Gerasimos. He has brought her gifts of the cheeses and chocolates she loves. She has brought him the autographs of Rex Harrison and Stewart Granger she garnered in New York for his collection, plus King Hussein’s signed Christmas card. (“That brave little king” is one of her heroes.) She herself collects nothing—the tributes and tutus are packed away in her brother’s house in England. Only the prizes won by Arias’s cattle are on display in the living room here. In her bedroom there are a few family portraits and ballet books. That’s it.

Rail-thin, Fonteyn no longer exercises, “since it used to be a process that led to something—the stage—and it no longer does.” Nor does the most musical of dancers ever listen to a note. “I haven’t quite figured it out, but I think it has something to do with motion.” Life here is like that at a Spartan spa. But Dame Margot is still graciously willing to trot out a few anecdotes for friends. Within minutes she is primly and happily darning away at a faded cushion while mesmerizing her audience with tales of meeting Marilyn Monroe: “my idol—she had perfect skin and even when she was standing still she just sort of undulated; she couldn’t control the effect she had on people, she just sort of was.”

Gerasimos mentions a picture he has of Fonteyn that bears a striking resemblance to Marilyn Monroe, and Dame Margot says, “I don’t remember that,” and changes the subject. She is equally ill at ease when people begin to mention having seen her dance. Later, sitting in the dark after the guests have left, she admits that she doesn’t like to look back and that praise makes her feel uncomfortable. “Since I never saw myself dance the way others saw me—three-dimensionally—I have no idea what they felt when they saw me. I can’t possibly know. Seeing myself on film is two-dimensional—it’s not the same, so I’m always at a loss to know what to say. All I was ever trying to do was what was expected of me. And I always felt inadequate.”

“How long did that last?”

“I’d say up to the end of my career.”

“But you don’t give yourself enough credit.”

“I never give myself enough credit.”

“Is the door to the stage completely closed now?”

“I don’t think the door is closed; I just don’t miss it. At least when you are taking care of a herd of cows they don’t come up and ask you to dance Swan Lake all the time.”

The fact is, however, that Dame MarX got Fonteyn does still work. In March she was in Venezuela helping to launch— as patrocinadora artistica—an interAmerican ballet company sponsored in part by the Organization of American States. When she was coaching the ABT dancers in Birthday Offering, which premieres in New York on May 8, she clearly enjoyed “putting right” a ballet that the company hadn’t got the hang of before she stepped in. Jane Hermann says that within a week Dame Margot was “gung ho. Knowing that she just lost Tito, we scheduled barely an hour or two for her a day, but by the second week she wanted three or four hours. She was really feeling very strong.” “Margot could be the director of a ballet company,” says Roland Petit, “because she has a sense of quality, of honor. Or she could teach. But if you ask her to teach it’s as if you ask Greta Garbo if she wants to teach. She’s irreplaceable. What she had she cannot teach.”

Late in the afternoons, Dame Margot will pile the dogs into the station wagon and ask Buenaventura to drive her to the beach. “There’s here and there’s the rest of the world,” she declares. She’s right of course. On this utterly deserted stretch of white sand and scalloped maroon and orange-colored shells, it hardly seems to matter what intrigues and plots are being hatched nearby or even far away. In order to walk through the sand, Fonteyn leans heavily on Buenaventura—who encourages her. “You need the exercise.” Most of those celebrated thigh muscles are gone now, and she who once airily covered acres of stage space like so many fluttering rose petals must measure every step. But then Buenaventura goes into the water, and as Dame Margot Fonteyn stands alone, watching a brilliant sunset begin to streak the horizon, the shape of her famous line and carriage suddenly takes hold; unconsciously, effortlessly, she becomes a frail and valiant ballerina silhouetted against the sky.

No Comments