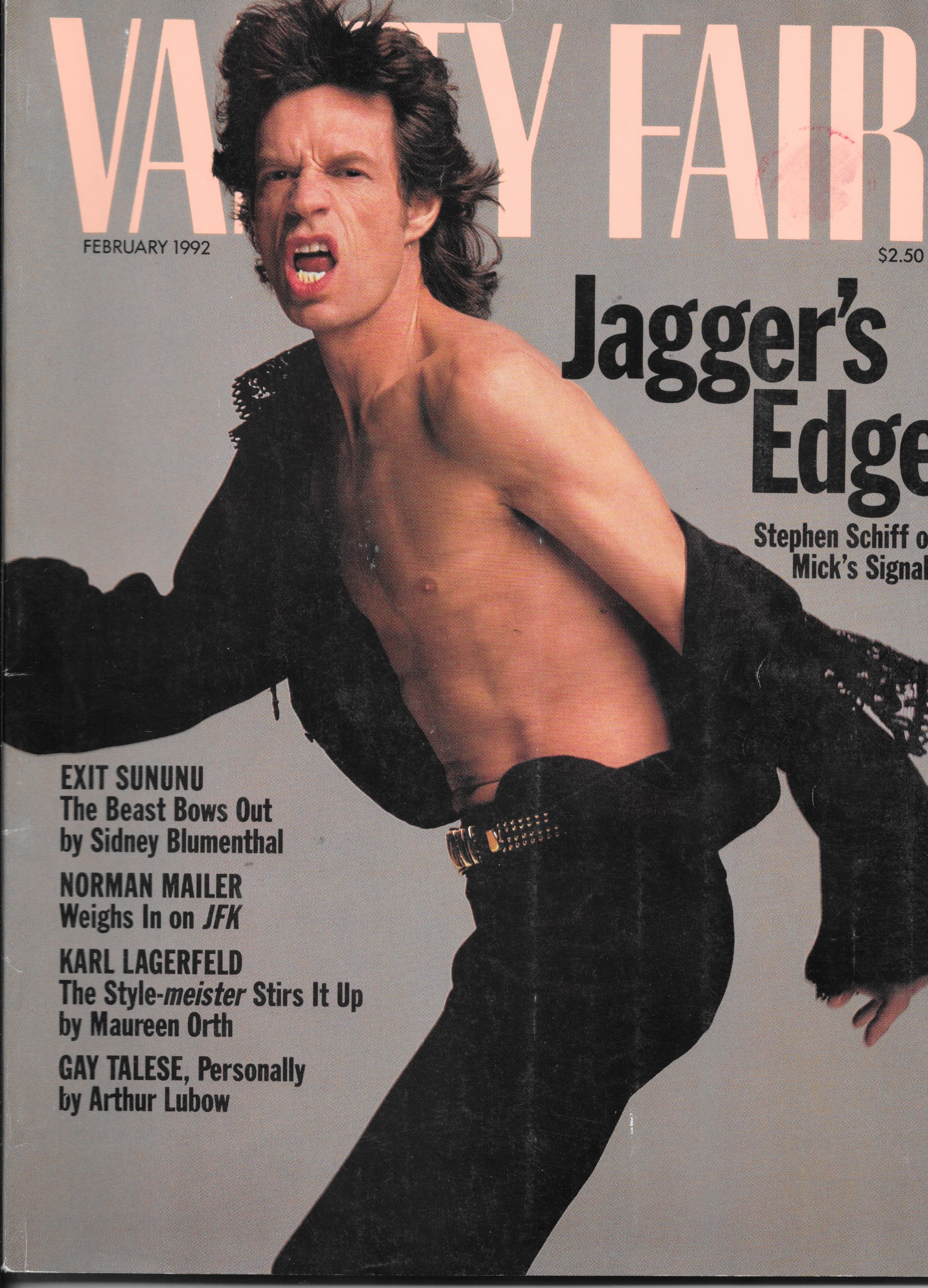

Vanity Fair – February, 1992

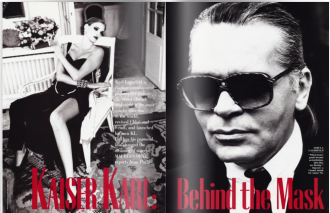

The pudgy little hand is pounding the Louis XV table, rattling the delicate porcelain and threatening to upset the shimmering vermeil flatware. “I’d prefer to have my success before me now, not behind me for twenty years, like other people.” Karl Lagerfeld’s piercing dark eyes are minus their usual cover of tinted glasses, though his Chanel makeup is on. “My past should only be addressed the minute I’m not part of it anymore and I stop doing what I’m doing,” he says vehemently.

The referent names are not so much as whispered over lunch in German-born Lagerfeld’s ornate Paris apartment, but two nights earlier the worldwide fashion elite and all of Paris society turned out for the opening of a forty-year retrospective of the work of Hubert de Givenchy. And in June, Valentino had commemorated his thirty years in fashion with a multimillion-dollar bash in Rome. “I hate this idea,” bang, “as if all those people are going to their own funeral,” thump, “I think it’s a nightmare,” whack, “the worst habit,” whack, whack, and “it’s strange it’s only done by not very trendy designers, eh?”

A few minutes earlier the subject was Yves Saint Laurent, who is widely considered in Paris to have slipped precipitously of late, but whose image is carefully controlled to make it appear he is in torture for his art. “Look, you want his life? Of course not, eh? I mean, I hear Yves is suffering, but you cannot suffer and bring out the same collection every six months.” Then, between bites of hot fish salad and sips of Diet Coke, “I stopped seeing him already fifteen years ago, because they [YSL and his partner, Pierre Bergé] all changed completely, but I don’t like to talk about those people. I am uninterested, because they’re not very trendy anymore, so really, huh?”

For the ponytailed, fifty-three-year-old Lagerfeld, not to be trendy is a most unfortunate condition: it signifies that you are B and the B-word, in the heady sphere of K.L., also signifies banishment. The most powerful designer of the moment states his fashion philosophy with a final bang. “When luxury goods become an institution, then they are Boring.”

Nobody watching the witty Lagerfeld at work “deconstructing” Chanel just before he showed his spring collection in Paris would immediately think institutional. It was more likely that Coco, who died in 1971, was rolling over in her grave. Her simple chain belts now had three descending tiers hung with a big fig leaf that banged right against the G spot. Her famous ropes of pearls were being reinvented in two new sizes: Ping-Pong-ball and golf-ball. There were Chanel cutoff jeans in bright-colored denim for $400 and quilted bags in traditional blue denim that the staff whispered would be fobbed off on the Japanese; her tasteful suits were in clingy stretch fabric, or shown in terry cloth for the beach, and worn with Minnie Mouse platform heels with cork soles. And just in case there was not enough product ID, Chanel’s quilted eye shadow came in a case the exact same shape as the top of the famous perfume bottles.

“I’m an intelligent opportunist,” Lagerfeld proclaims. “In fashion you have to be. Pierre Bergé says about me, ‘He’s not a designer, he’s a mercenary.’ I like the idea of doing things you’re not supposed to do.” In sixteen collections a year—for Chanel, Fendi, his own Karl Lagerfeld signature line, and Trevira fabrics, Lagerfeld labors ceaselessly to get onto the charts in a field even more fickle than pop music.

He has been wildly successful. “When Lagerfeld took over the Chanel collections, they had one foot in the grave and the other on a banana peel—it was Seconal City,” says Marian McEvoy, editor of Elle Decor, who used to cover them. The old-line Chanel dressed the wives of industrialists and French ministers. Today, according to Barbara Cirkva, who heads the Chanel boutiques in America, “the average age of the customer has dropped from the mid-fifties to between thirty-five and forty-five.” There are Chanel boutiques in Nashville and Oklahoma City and on the island of Guam. Clearly, Chanel has become the upscale uniform of choice. “I never thought for one second I could bring it that far,” Lagerfeld confesses. But he has—in C’s. Declares Women’s Wear Daily publisher John Fairchild, “Karl Lagerfeld is the designer today with the most influence, the only designer who could bring Chanel to such a peak.”

The man traffics in trends—if you sneeze you might miss one. Who would have guessed a few years ago that he would be able to get women to run around in Chanel jackets with nothing but leggings on the bottom, or that MTV’s “Downtown” Julie Brown would be sent to Paris to review his latest signature Karl Lagerfeld collection, lean, transparent, and tight, (“I dunno, Karl, ” said Downtown Julie, who was dressed in black velvet short-shorts trimmed in fur, black fishnet stockings, and a strapless black lace bra. “That look was a bit more than I could wear.”)

He’s got to destroy Chanel, in a way,” observes International Herald Tribune fashion editor Suzy Menkes. “Otherwise, he just becomes a caricature of her.” Says Lagerfeld, “Only the minute and the future are interesting in fashion—it exists to be destroyed. If everybody did everything with respect, you’d go nowhere.”

That’s how Lagerfeld answers the critics who say his recent work for Chanel—which borrows liberally from downtown hookers and hustlers as well as from uptown debs on drugs, in tank tops and tulle ballerina skirts—is vulgar. It also anticipates the skeptics who wonder if the high-flying Chanel, which employs legions of lobbyists, lawyers, and detectives to protect it against counterfeiting, isn’t moving right up to the undrawn line where one becomes so successful there’s a risk of being knocked off and devalued à la Louis Vuitton. Lagerfeld begs to differ. Maybe you are longing for those chic-of-the-week $1,000 Chanel motorcycle boots?—exact replicas, except for the trademark C’s, of the $70 variety he appropriated from the look of S&M boys in leather bars fifteen years ago. But in Lagerfeld’s head they are already gone, out. When a model started to wrap a plastic chain around her thigh backstage at a recent Chanel show in Paris, he stopped her. “Of human bondage? No, we did that before.” He was two collections ahead with—are you ready?—quilted clogs for the enchanted forest. The theme was back-to-nature, “but not boring ecology.” Lagerfeld had his models carry sheaves of wheat, the symbol of abundance, wrapped in $650 iridescent-bead necklaces that probably cost less than $50 to make. “Here, carry this,” he said to one of the most beautiful girls in the world just before she went down the runway. “It means money—that’s all they care about anyway.”

The next day the International Herald Tribune ran a photograph of one of Chanel’s simplest new, longer-length suits ($2,260), paired with a basic tank top ($545), bobby socks and two-tone plastic Great Gatsby golf shoes ($660), and really pared-down accessories, meaning there were only six pieces of costume jewelry on the model, including the $745 poured-glass earrings and the $1,000 chain belt with dangling C’s. To have bought the whole outfit would have cost $9,290. Lagerfeld is convinced it will all sell out. Why? It’s not just that Chanel strictly controls the amount of its inventory so that there will always be pent-up demand, but also that Lagerfeld understands the importance of creating fantasy.

The reason American cars don’t sell anymore is that they have forgotten how to design the American Dream,” he says. “What does it matter if you buy a car today or six months from now, because cars are not beautiful. That’s why the American auto industry is in trouble: no design, no desire.” Similarly, “Give me the name of one trendsetting actress. They are all sloppy and they all talk too much. They’re all into political causes. Maybe that gives them a nice feeling, but people want dreams too.”

“Still, Karl, do you really think women are going to spend $1,500 on a little Chanel terry-cloth jacket?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Why?”

“Ah, this is the mystery of fashion.”

Tricycles are strewn across the cobbled courtyard on the Rue de l’Université; twenty children, all family of the elderly American-born countess who rents to the designer, leave them lying about. Normality ends there, however, and the private world of Karl unfolds. It begins as soon as the door to his wing of the hôtel particulier is opened and the first whiff of powerful potpourri hits—the eighteenth century envelops, a moment of perfection for French civilization, the spirit of which Lagerfeld says is “the only real constant in a life based on change.”

Once up the majestic marble staircase, one is surrounded by damask and gilt, tapestries and canopies, priceless objects from all three Louis. No wonder Lagerfeld used to powder his ponytail and often still wields a fan. It must be hard to stay out of high heels. Lunch is supposed to be at 1:30, but time in this rarefied atmosphere is only to be used, not observed, and when the door to the study is still fermée, the maid never so much as knocks.

Would Mme. De Pompadour or Voltaire feel at home here? Undoubtedly, if they and other Enlightenment-era ghosts wanted a place to haunt, these dark rooms would be ideal. Certainly the twenty imposing paintings hung on the walls of the smallish salon provide endless fascination, particularly the one of Christ just down from the Cross with bare-breasted guardian angels protecting him from the Roman soldiers (its original owner was Marie de Médicis, wife of Henri IV). To further tantalize, there is just a glimpse through the open doorway to a blue bedroom with a gilded sleigh bed, once owned by a grand duke, and walls covered in silk-velvet frappé made in Lyon according to the records and machinery that still exist from two hundred years ago. Then, suddenly, out of nowhere, blasts the old R&B song, “It’s in His Kiss.”

Lagerfeld’s universe is one of luxury and irony, lived at a level of European opulence and breadth no American could possibly muster.

Is he rich?

Very. He was born rich.

Then, is he different from… ?

Very.

The iconoclastic philosophe of fashion lives at once frozen in time and at the cutting edge of moderne; the software in Karl Lagerfeld’s computerlike brain never shuts down. “Style is about defining things, and Karl has to define things all the time,” says the writer Joan Juliet Buck, who was close to Lagerfeld in the seventies. “It’s like a search-and-destroy mission for stuff, ideas, shapes, colors, correspondence. Karl can outlast anybody in terms of coming up with stuff.”

He is also a very wealthy freelancer, collecting hefty salaries from Chanel and Fendi, and sharing in the profits from his own line and from the licensing of his name for several top-selling perfumes. He couldn’t care less that KL—which, defying recessionary times, has increased its revenue by 50 perfect in the last year to about $20 million—may be sold to the British Dunhill Holdings P.L.C. (The firm also owns Chloé, where Lagerfeld got his start.) Perhaps it’s because he’s always had money that the pride of ownership holds no interest. “My currency is my work,” Lagerfeld says. “I don’t want to have an empire, I don’t like people dependent on me. I prefer to have a success like this,” and he makes an upward, wavelike curve, “not like this,” and he slices the air vertically.

Imagine, then, a creator with a keen nose for business whose work spans the globe, yet who disdains the telephone as well as vacations. Imagine that in addition to meeting his sixteen fashion deadlines a year he may at any one time be spending a half million dollars on a single chair to add to his collection of eighteenth-century furniture—one of the most extensive in the world—or renovating one of his seven meticulously furnished houses and apartments, or designing sets for operas and illustrating children’s books, or taking all the photos for the Chanel and Karl Lagerfeld advertising campaigns.

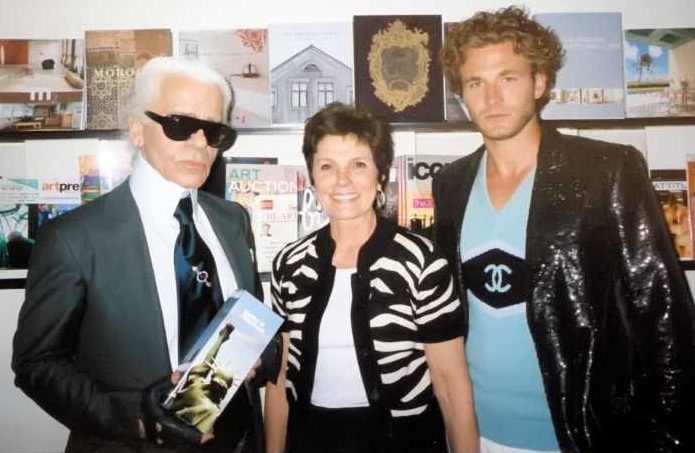

But perhaps Lagerfeld’s greatest love is books: the eighteenth-century ideal of the cosmopolitan mind and intellectual control is foremost. His discipline is to awake before the dawn to begin his strenuous mental aerobics, the voracious reading of biographies and history, art magazines and newspapers in several languages (as a result, says Buck, Karl Lagerfeld knows all the gossip about all the dead people in the world). Next, he begins his voluminous correspondence, each note and then fax after fax handwritten to a worldwide network—“I have my own secrete service.” They keep him informed up to the nano-nanosecond.

“Karl is at the center of an extraordinary cobweb. People write to him and tell him things; the world comes to him,” Says his close friend Princess Laure de Beauvau Craon. “He prefers to be alone. He likes his own company, which must be very entertaining.” The puns and word games flow in four idioms: German, the mother tongue; French, the language of the adopted country; English, picked up as a child because the dialect of northern Germany, “ was very similar to English”; and Italian, because “to those of us from the North, the Mediterranean represents danger.”

And what could be more fun than intrigue? Is there something afoot in the land of one of his residences, a castle here, a château there, dotted across France, Italy, Germany, and Monaco—“Monte Karl’s” official residence to avoid French taxes. More important, has anyone given him up in the last twenty-four hours whose name should be added in the lengthy Banished list. “The key to understanding Karl, ” says one of his inner circle, “is that he can bear a grudge.”

“He is afraid of one thing in his life: betrayal,” says his close friend and “private curator,” Patrick Hourcade. “As soon as he discovers people do things behind his back, he closes the curtain.” On the other hand, Hourcade says, “he loves to stick it, and he knows how journalists like that, too. The result, in fact, is publicity for everybody.” Lagerfeld himself explains: “There are no second options. It’s when they think they know better than I do, when they get too big heads, they need a fresh shower, or when they use a private relationship for a business purpose.”

The first work shift for Lagerfeld lasts from dawn until lunch (which is always taken at home, and usually alone, in a dining room with a giant television screen). In preparation for the second half of his day Lagerfeld will spend the morning in a fresh white piqué robe, sketching alone in his study while listening to music that ranges from one of Proust’s favorite composers, Reynaldo Hahn, to Japanese Muzak, to the latest top ten—he has been known to drop by a record store and buy three hundred tape cassettes at a time. A lot of his detailed sketches will go right into the garbage can; sometimes two weeks will pass without his delivering anything to his top-notch design teams, who by then are on the verge of despair.

But they have learned to adapt to his late-afternoon, early-evening, even dinnertime arrivals. Meanwhile, his minions will keep busy—Lagerfeld creates a team that will bring him not only the best of craftsmanship but also the New. Several leggy, dark-haired girls are among his muses—twenty-eight-year-old Antoinette Ancelle, an exotic pale-skinned beauty from a tiny village in Burgundy is his current inspiration at Karl Lagerfeld, and she doubles as his button designer, which means she combs flea markets, constantly looking for specimens and ideas. Ancelle admits that “it’s hard to have a private life” with the hours Lagerfeld keeps, “but one adapts to him or makes another life. I don’t say much to him, because he knows me very well—you don’t have to speak much for him to know you.” Still, having seen many come and go during her five years with Lagerfeld, she keeps a certain distance. “To be too close, it’s like fire. The fire, it’s very pretty, but you get closer and closer and at one moment you get burned up and finished. Moi, I warm myself, but I never burn.”

Many years ago, Lagerfeld’s fortune-teller told him that small dark-haired women would be important in his life, but that he had to be careful of them, too. Mme. Gabrielle Aghion—small and dark, Egyptian and French, widely believed to have been a model for Lawrence Durrell’s Justine—hired him in 1963 to design for Chloé. There he earned fame as a designer in the seventies, and Parfums Lagerfeld was created to license the popular Chloé fragrance. He and Mme. Aghion fell out, he says, when the licensing started bringing him more money. He left Chloé in 1982 for Chanel, lured there by short, dark-haired Kitty D’Alessio, then president of American Chanel. She crossed him, he says, by using an advertising photo that he did not like of (tall) dark-haired Inès de la Fressange, the popular face and model of Chanel in the eighties. D’Alessio, who allegedly plotted against Lagerfeld’s top assistant, Gilles Dufour, and took credit for editing many of Lagerfeld’s fashion ideas, was also a staunch backer of the talented American designer Frances Stein (average-dark), who still produces many of Chanel’s fabulously successful accessories. Lagerfeld, who says Stein “got a big head,” routinely bans her creations from the runway, and thanks to him she no longer designs separates for Chanel. By 1986, D’Alessio, who also “got a big head,” was out as president.

“The good news,” Lagerfeld said at the time, “is that Kitty D’Alessio has been made ‘Director of Creative Projects.’ The bad news is that there are no Creative Projects.”

So far, the position of Coco Chanel, her dark bob notwithstanding, remains secure.

L’affaire Inès, however, riveted all of France. The front-page brouhaha that ensued in 1989 after Lagerfeld fired the photogenic beanpole aristocrat, his top model, muse, and closest female friend, did get terrific publicity for them both, a fact not lost on master media manipulator Karl. Inès, who no longer cares to comment, was said to have dared to become involved with another man, and also accepted, without checking with Lagerfeld first, the offer to be the face of Marianne, the national symbol of France. Lagerfeld said at the time that posing for Marianne was unacceptable and très bourgeois. Today he claims that the whole thing was made up for the press, that Inès, too, “got a big head,” that in fact it was Alain Wertheimer, the tough young owner of Chanel, who decided she should go.

“The last two years she wanted more money. M. Wertheimer saw no reason—she was very well paid and unknown outside of France. Her high days on the runway were over—now the girls are between fifteen and twenty and she was already in her early thirties. She had a bad attitude, eh? One day she embarrassed M. Wertheimer by asking for more money in front of other people. So he told me, ‘Invent something to get rid of her.’ Marianne was an excuse, a total invention—I couldn’t care less.”

Lest anyone thing he’s simple to read, Lagerfeld is also extremely generous with those he cares for. A number of ladies he knows get free dresses, he has made lots of wedding gowns for free, and he says he has even given away sable coats from Fendi. “I throw money out the window. I vaguely know how far I can go, that’s all. I like overspending, because you stay more alive—you’re ready for the battlefield once again.” Of course, there are times when cynicism overwhelms munificence. “Here, take this,” he once said, throwing an antique Mme. Grès dress at a point midway between Paloma Picasso and Anna Piaggi, the eccentric Italian he has often sketched, and watching as they lunged for it.

Still, gifts are almost like breathing. At an hour when the rest of Paris has barely had it’s café au lait, Lagerfeld’s discreet manservant, Brahim, will start ordering the lush bouquets and the thoughtful books that will be sent to that day’s favored, usually in pairs, for the city house and the country house. “Karl Lagerfeld is the least selfish designer I know,” says John Fairchild. Then Brahim will chauffeur certain pieces of the correspondence around town in the big dark-gray Bentley. (“Thank God we still have chauffeurs who can deliver our notes,” said Liliane de Rothschild on the day she received her nineteenth bouquet of the year from Lagerfeld—her butler keeps a list.)

Undoubtedly Lagerfeld will also contact his old friend Hourcade, who shares his passion for the eighteenth century, but who is also fast becoming the ice-skating impresario of France. “Actually, Karl is most interested in a very short period at the end of the reign of Louis XV, just before Louis XVI, after the first trip of Mme. De Pompadour’s brother, the Marquis de Marigny, to Italy,” Hourcade earnestly recounts. The two have spent seventeen years perfecting the garden of Lagerfeld’s castle in Brittany, and now that the castle is undergoing renovation they have constructed a perfect scale model of forty rooms, complete with precisely labeled furnishings inside.

Lagerfeld has also been drawn back to Germany of late and is renovating a house in his native Hamburg, on the Elbe River not far from the posh Baurs Park area, where he spent his youth. All of his non-fashion profits go to German children’s charities, and he is designing, for free, the interiors for a luxury hotel in Berlin. (In exchange he gets an apartment for life, including room service.) Nonetheless, he doesn’t harbor much hope for the renewed nation: “Germany cannot be what she used to be, because there are not enough Jewish people. My mother always said there was some sparkle only the Jewish culture could bring. Germany without Jews is a boring, materialistic country.”

Of all his residences it is the one in Brittany that has captured his soul. Lagerfeld’s mother is buried in the private chapel there, as is Jacques de Bascher, his flamboyant, aristocratic, and closest friend for nearly twenty years. De Bascher died of aids in 1989, at thirty-seven, and his death has left a gaping hole in Lagerfeld’s life—he still cannot speak of Jacques without bursting into tears. In the wake of his death, Lagerfeld, who says he has never been decadent—“I’m not one who can get lost”—rarely even socializes; these days he stays home and reads and watches videos far into the night. He has also completely changed the way he dresses, exchanging a lifelong uniform of perfectly tailored Parisian suits, shirts, and ties, no matter the season, for looser black mourninglike garb of Japanese design.

Jacques de Bascher was an infamous character who looked like a thirties movie star, dressed like a nineteenth-century dandy, and was kept by Lagerfeld, whom he called Mein Kaiser, though the two never lived together and, according to Lagerfeld, were never sexually intimate. He says it was “amour absolu, detached from all the problems—money, family, physical relationship—that can ruin a relationship.”

Once, when Lagerfeld gave an eighteenth-century ball, Jacques came as the Rialto Bridge. Another time Jacques was officially engaged by a cardinal to the equally wild Diane de Beauvau Craon (whose grandmother was an Italian princess), at a medieval Vatican ceremony still accorded certain members of Italian nobility. Lagerfeld gave her a full-length black ermine cape from Fendi for the occasion and assumed he would take care of the “eight kids they announced they would have,” but Jacques and Diane lost interest after the visit to the Vatican was over. Jacques would brag about his weird aristocratic ancestors (among them Gilles de Rais, a companion-in-arms of Joan of Arc known for torturing little boys and girls). He would throw wild parties where drugs abounded, and would drift easily back and forth between the Lagerfeld and Saint Laurent camps. Many found him utterly charming, others unsavory and creepy.

“He was the wildest person in the West,” says Lagerfeld, “but this was like a double life—a kind of Mr. Hyde and Dr. Jekyll, and I had nothing to do with that. If I had had the same kind of life I wouldn’t be here anymore, because he died from that.”

“He has all the qualities of the virgin,” says Gilles Dufour, the studio director of Chanel and Lagerfeld’s collaborator for twenty-five years. “He has great discipline. He does not need people around to be happy—he’s very much into his dreams, his fantasies, and his books.”

“Karl has always been about being above human emotion, human frailty, the chatter and passions that consume us,” Joan Buck adds. “He could look at Jacques’s excesses from above, in a princely fashion—he himself was too grand.”

When asked if he considers himself happy, Lagerfeld responds, “Happiness, in my sense, doesn’t say anything, you know. The only person I really cared for died, so—poof—I don’t care.” Suddenly Lagerfeld emits an involuntary sob, but he goes on waving his hands as if to drive the grief away. “But it also gives you a kind of freedom—now I’m ready for everything because I’ve got nothing.” Lagerfeld’s face, which usually radiates mischief and energy, is a terrified mask of tears and pain.

“I’m not a family-minded person, and he was the only thing that gave a kind of sense to things.… But the strange thing is, it wasn’t physical—it had nothing to do with that. I hate the atmosphere of boys—I never went to a gay club in my life, nearly.… No, it was like family without the burden of family, and he brought to my life a kind of sparkle nobody else ever will. Maybe there is one person in life for you and that’s all.”

Lagerfeld mentions the chapel where both Jacques and his mother are buried, and says he will never join them there. Dust to dust? “Dust to dust.” He chokes. “I like the idea of starting from nothing and going to nothing. What I leave behind I don’t care—paradise now.… Finally, the purpose of life is life.”

‘I was born to be alone.” Lagerfeld says a fortune-teller first told him that when he was only eighteen, but he knew it already. As a child he preferred to sketch than “to play with the peasants.” He wouldn’t need anybody else, the fortune-teller prophesied. “ ‘There are things you can have and things you cannot have. One cannot have everything, and nobody can adjust as well to that as you.’ She told me, ‘You can never have a normal family life, so whatever the standard image is of happiness, family, friendship, bonheur, for you it doesn’t work. Stay alone, watch the world—you can get everything you want if you are not ready to conform. Stay away from everything that is normal life.’ Strange, eh?”

Of course, there was nothing terribly normal to begin with. Lagerfeld was actually born “Lagerfelt” in Hamburg, in 1938, when his German mother was forty-two and his Swedish father was over 60. “I was treated like a grandchild in a way.” His parents were rich, cerebral, and cultivated. His mother had been married in a Vionnet gown, and he was told she was the first woman in Europe to get an aviator’s license, though he never saw her fly. She mostly smoked and read and played the violin three hours every morning—until one day she stopped forever. At dinner his parents would discuss in French things not meant for small ears, but their favorite sport was arguing about the history of religion—both his parents were Catholic, a decidedly minority religion in northern Germany, and both had fallen away. “When my father became very old he resented that, because she pushed him out of the church,” Lagerfeld says. “He thought he would never die, because his parents had lived to be nearly a hundred and it was his dream to survive my mother. He hated the idea of her living happily, spending his money without him—he couldn’t stand that idea.”

The money came from controlling 57 percent of the condensed-milk market in Europe—Lagerfeld’s father had gotten the concession from Carnation after World War I. The Germans wouldn’t buy cans with an American label on them, so he changed the name to Glücksklee, or Cloverleaf, and that bought a 1,200-acre country estate, Bissenmoor, where little Karl and his “much older” half-sister from his father’s first marriage (his first wife had died) were sheltered from the war. Lagerfeld no longer speaks to his sister: “She did not behave well after my father’s death in 1967, and I never saw her again.”

As a war baby Lagerfeld was much more than privileged. “We went through the worst period of the war without knowing it—this was something my parents achieved which was unbelievable,” he recalls. It didn’t seem odd that there were fifty-six refugees sharing the house with the family. The Frenchwoman who became Karl’s French tutor when he was five was only one of many who tended him. He grew up hearing the story that at four he demanded a valet to dress him and at a Christmas dinner a few years later he screamed and would not stop, because his parents had bought him a copy of the wrong eighteenth-century portrait. (He got the one he wanted, of Frederick the Great at a court dinner, and it still hangs over his bed at Le Mée, his house on the outskirts of Paris.) When he wanted his mother to read him children’s stories, she told him he would have to learn to read himself, and he did. When he entered the nearby country school he shot ahead two grades.

“I was spoiled, I hated the idea of being a child,” says Lagerfeld, who can’t really remember any childhood friends. “They all had slave parts. I had no need for company—I had the feeling the world was mine and nobody could say anything. What young Karl really loved to do was sketch. “I was born with a pencil in my hand and I can’t remember ever wanting to do something other than what I do today.” Sometimes he would sneak up into the attic to pore over old Vogues and sniff around the huge trunks belonging to his father’s first wife. “I was interested in what people used to wear—I loved to look at old photos. I had the feeling I was born too late—the twenties and the thirties were better times.”

At first he thought he would like to paint portraits, but that idea was quashed by Mater. “My mother said this was ridiculous, but ‘if you want to learn to paint, you will learn to paint. You are totally ungifted for music.’ ” He also credits his mother for his rapid-fire speech. “She told me, ‘I can’t bear to hear your ridiculous stories; finish them before I get to the door.’ ” It was also thanks to her that he never smoked. “ ‘When you smoke you often see the hands and as yours are not very beautiful … ’ Well, you can imagine what this did to a fourteen-year-old boy. I never touched another cigarette.” His mother was, of course, “bored to death” in the country, and she remained bored when they later moved to Hamburg, which was nothing compared with Berlin, where she had lived before marrying.

Perhaps Lagerfeld’s boredom phobia can be traced to these early days. Yet, in recounting these tales he seems unaware of how demanding his mother sounds to his listener. “Maybe she was severe, but things were done in a very light way, eh? I wanted to please her because she hated everything second-rate.” Certainly, she didn’t suffer fools gladly. Many years later, after her son had become a famous designer and she was living in the castle in Brittany he has since inherited from her, a television-commercial producer demanded to know why there was a little wooden plank overhanging the small pond in front of the house. Lagerfeld’s mother, who by this time had striking white hair and dressed in long skirts over slacks, with delicate blouses and a monocle hanging around her neck, threw open the downstairs windows and proclaimed, “It is there in case the goldfish want to get out and take a walk in the garden.” She then slammed the windows shut.

Karl was fourteen when he announced he wanted to leave Hamburg, a port city on the Elbe River near the North Sea, which billed itself as “the door to the world,” to go to Paris and become a designer. “You are not snobbish, my son,” his mother commented dryly, “for you want to be a fournisseur [supplier].” “I was allowed to try whatever I wanted, but I had to prove I was serious about it—there was no freaking out.” Arriving in Paris and never having liked the shape of the l and the t together at the end of his name, Karl created “Lagerfeld” at customs and that was that. Less than two years later he won a prize from the International Wool Secretariat for designing a coat. Yves Saint Laurent, seventeen, won the dress prize, and the two have been competing ever since. “You have to understand that, to the French, Yves Saint Laurent is a god,” says fashion journalist Christa Worthington, “but Karl Lagerfeld is a German.”

The youthful Karl, so well bred, was horrified by the tawdriness of the fournisseur’s existence in those days. Balmain hired him and made his coat, but life in the haute couture was not as he had imagined. “I thought the people were quite cheap, the intellectual level very low,” says Lagerfeld, who by then was deeply interested in history, literature, and languages. “The minute you left the gilded salons it was the worst—mean, vulgar, filthy. People were treated like dirt. But I wanted to stay in Paris and so I said, Shut up, don’t think about anything, because you are here in Paris to learn.”

Learn he did, and in the process became a kind of high-style hit man, taking aim at both ends of the market, designing shoes, fabrics, furs, china, pencils. It always started with a sketch and Lagerfeld always worked freelance; worrying about the bottom line would inhibit creativity and encroach on his freedom. In 1963 he was one of four hired by Mme. Aghion and her financial partner, Jacques Lenoir, to design a pioneering line of luxury ready-to-wear for Chloé.

The four designers completed furiously until there were three and then only two, Lagerfeld and Graziella Fontana, who worked side by side for seven years until Lagerfeld, having mastered Fontana’s technique of tailoring, triumphed in 1972 in a kind of lace leukemia. “Karl could do Graziella, but Graziella could not do Karl,” M. Lenoir once explained to Women’s Wear, diagnosing it as a case of “the white corpuscles eating the red.”

“I am not a Woodstock person,” Lagerfeld says in utter seriousness. “For one thing, in the sixties I hated the smell” So when Saint Laurent as a full-blown couturier was taking the Mao jacket from the barricades of ’68 and turning it into the height of chic, all the while becoming French society’s darling, Lagerfeld was at the center of a younger, more outré group. The designers were still good friends then—they went shopping for Art Deco together, and both new Andy Warhol—but it was Lagerfeld who played the role of the bored German aristocrat in L’Amour, Warhol and Paul Morrisey’s version of How to Marry a Millionaire, with Donna Jordan and Jane Forth. As the rival camps began to assert themselves in the mid-seventies, Karl was always considered the fun one, looser and more accessible. And there was no majordomo playing gatekeeper, as Bergé did for Saint Laurent.

It was Lagerfeld, in a semi-private show for one of his shoe lines, who sent the black model Pat Cleveland down the runway in nothing but his shoes and a pink feather in her pubic hair. And Lagerfeld who encouraged his older Italian muse, Anna Piaggi—whom he sketched again and again in male and female costumes from all periods of history—in her sartorial excesses, which featured baskets of dead fish on her head and feathery pigeon carcasses at her waist. But he could also be cruel. Another of his models was an unattractive Beatnik artist, the late Shirley Goldfarb; Lagerfeld had her on the runway, it seems, just to make fun of her. Then she did something to displease him and he said, “Ugly is one thing, stupid is another, but ugly and stupid is too much.” She was sent away. “All monsters of creation are monsters in other ways,” observes Marian McEvoy.

Lagerfeld was an encyclopedia of retro who reworked fantasies of the past for Chloé—a postmodernist before the term was coined. He haunted the flea markets for antique designer clothes and fabrics; he pored over old magazines and photos and learned the histories of hundreds of Art Deco brooches. He collected old Vionnet, Poiret, and Mme. Grès dresses (never Chanel), and made over the twenties and thirties or the eighteenth century—whatever, it was all referential. When Chanel beckoned, Lagerfeld had already grasped the fantasy and possessed the background and research to understand how to make “Mademoiselle.”

The timing was perfect. “The growing yuppie movement needed status symbols,” says Allan Mottus, who publishes a newsletter on the beauty-and-cosmetics business. “There weren’t a lot around and Chanel was one of the great ones.”

Following Chanel’s trunk show at Bergdorf Goodman last September, the store did a million dollars’ worth of Chanel business in three days. On the West Coast, the story is the same: “L.A. is gaga for Chanel,” says Mary Rourke, fashion editor for the Los Angeles Times. “Remember,” says Bergdorf’s new C.E.O., Burton Tansky, “the center of the business is not biker boots and leather jackets—it’s very, very beautiful suits, dresses, and jackets used in various ways.” Says the Herald Tribune’s Menkes, “In my view the American woman longs for a uniform. You don’t see so much Chanel on the streets in Europe. You do in Hong Kong, which is another aspirational society.” Mottus estimates that the privately held and secretive Chanel empire does more than $300 million in fragrance and cosmetics retail sales worldwide and another $100 million in accessories. Haute couture, by contrast, is a loss leader these days; even Arie Kopelman, current president of American Chanel, says the importance of the “halo effect”—where the fashion lines ring up sales for the far more profitable cosmetics and accessories—is “overblown.”

Thus, in its zeal to get the best space and location for its boutiques and to tightly control presentation and supply, the company has a reputation for being a very tough negotiator. Lagerfeld’s renowned ability to perform for the press is another, inestimable advantage. Explaining the Chanel marketing strategy, Kopelman puts “the support of the press” second only to “the clothes on the hanger.” “I’ve found over the years that Karl’s very easy to deal with,” says Fairchild Publications president Michael Coady. “He understands the role we play, at least, and he rides the ups and downs—he’s always been less emotional about coverage than most.” Is there a moment when Karl Lagerfeld, who once hosted a live TV talk show in Germany, is at a loss for words? Never. “He’s good for the whole business, because excitement swirls around him,” says Bergdorf’s Tansky. “He loves to create controversy and he’s catty.”

It was quite a show in Lagerfeld’s Rue Cambon studio the day before his Chanel spring collection debuted, with supermodels Linda Evangelista, Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, and Christy Turlington there for their final fittings. At the last minute, hemlines were being ripped out and pulled downward. Evangelista, with flame-red hair, was being coached to pose like a legendary Chanel model from the fifties, Marie Hélène Arnaud, whose face was on the cover of a 1954 Spanish magazine Lagerfeld was brandishing while standing at his desk and eating a lunch of three grilled hot dogs.

On his desk were seventeen trays of bangles and beads, and about twenty-five friends and staff members were gathered to watch or help with decking out the models for the next day’s show. Tacked onto the bulletin board were 175 numbered sketches, “the passage.” American Vogue was already there when, in the early evening, a troika from The New York Times walked in; the ranking member perched on a chair at Lagerfeld’s elbow. Within minutes the fashion mavens were being proffered pricey baubles as well as drawings by Christian Bérard, a thirties set designer and contemporary of Coco Chanel’s, which Lagerfeld had just purchased at auction. Why not two? Why not four? But of course. And here, have the latest choker, and this $1,300 necklace. All the booty was oohed and aahed over, and promptly disappeared into a large black tote. The ringleader later told me that some of Lagerfeld’s largess was returned but some of the expensive loot was kept, as is frequent custom in the fashion press. The posters, she explained, “were like a Christmas present from a friend,” and a pair of glass-bead earrings ($745) were a must: “God forbid you don’t have them on next time.”

Evangelista was now in front of the mirror with the zipper in back undone so that her skirt could be pulled down longer. “You know, they have no hips, but they have buns,” Lagerfeld told the fashion editor. “They don’t need a bathing suit, just a double bra.” Lagerfeld’s words gave him inspiration; out came his pencil box, and in less than five minutes he had produced and given the Times editor a more personal souvenir—a signed sketch of “the double-bra bathing suit.” As the Times delegation trooped out, air kisses all around, Lagerfeld whispered, “I hope you like my show tomorrow.” “Oh, I will, ” the editor promised.

Backstage the following morning Lagerfeld was full of fun but slightly nervous. He shooed away the paparazzi, who hoped to watch the models undress. “I don’t want any girls photographed while changing—non, non, we’re not running a porn shop.” He eyed the sleek, black, six-foot-seven-inch, and exquisitely tasteful André Leon Talley from Vogue, who was wearing a suit of banana-yellow-and-teal plaid lined in baby-blue satin. “I know you’re not interested, but the others are here for pussy.”

A few minutes later he asked Talley, “It’s fresh enough? No doubts?”

“No doubts,” Talley, an old friend, answered.

Many in the audience, as it turned out, felt that the spring show did not pack the punch of Lagerfeld’s previous fall collection—but not his fashion-editor friends, who assured him it was divine. Thank God. For yet another season he has dodged the B-word.

But there would be no rest for Kaiser Karl. With few exceptions, the New York spring shows that followed in November were dreadful, which only meant that those desperate tastemakers would again be craning their Chanel-roped necks in Lagerfeld’s direction in February, at the next show. In a frenzy of expectation, they would look to him for novelty and spirit, and, as usual, he would probably deliver. What can the chic set drowning in C’s expect? My guess: quilted condom holders for the newest Chanel handbags.

No Comments