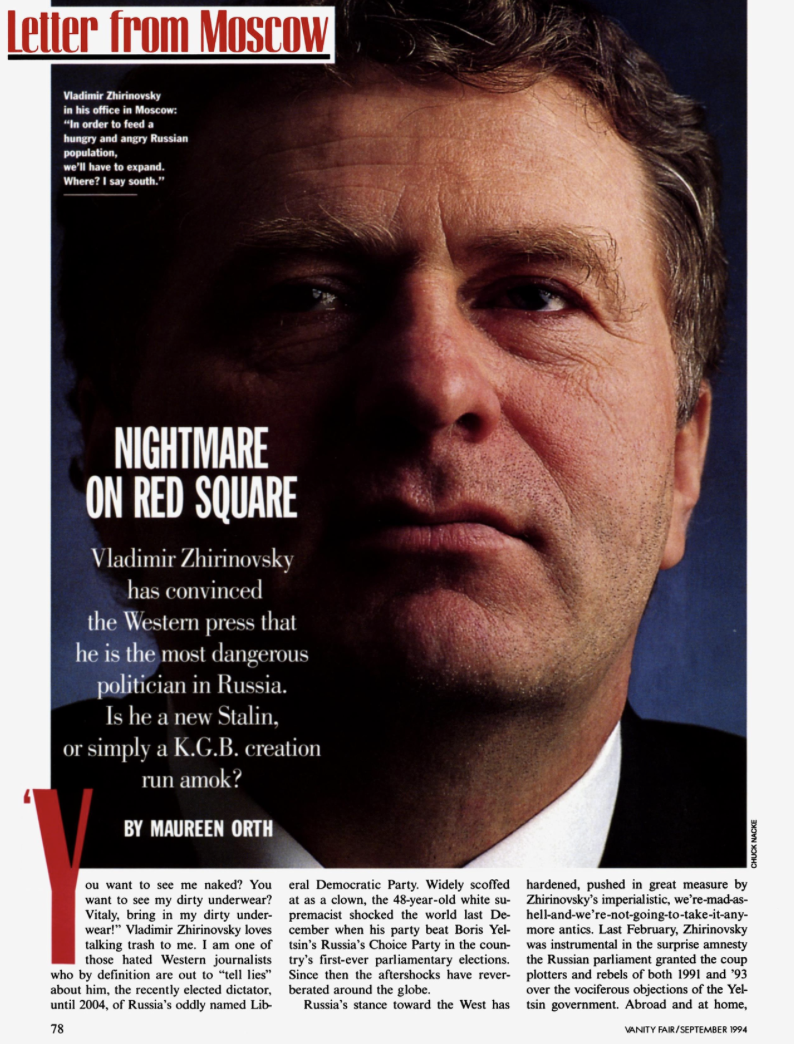

Original Publication: Vanity Fair – September, 1994.

“You want to see me naked? You want to see my dirty underwear? Vitaly, bring in my dirty underwear!” Vladimir Zhirinovsky loves talking trash to me. I am one of those hated Western journalists who by definition are out to “tell lies” about him, the recently elected dictator, until 2004, of Russia’s oddly named Liberal Democratic Party. Widely scoffed at as a clown, the 48-year-old white supremacist shocked the world last December when his party beat Boris Yeltsin’s Russia’s Choice Party in the country’s first-ever parliamentary elections. Since then the aftershocks have reverberated around the globe.

Russia’s stance toward the West has hardened, pushed in great measure by Zhirinovsky’s imperialistic, we’re-mad-as-hell-and-we’re-not-going-to-take-it-anymore antics. Last February, Zhirinovsky was instrumental in the surprise amnesty the Russian parliament granted the coup plotters and rebels of both 1991 and ’93 over the vociferous objections of the Yeltsin government. Abroad and at home, he has cast himself as the flamethrower who personifies the despair of millions of Russians who helplessly watch their money become worthless as thugs take over their neighborhoods. With the economy in shambles, they naturally feel betrayed by democratic reforms.

Zhirinovsky is also a drawing card with the military, who sense that they are more defeated now than if they had lost their every division in battle. He plays the ultra-nationalist, capitalizing on xenophobia and anti-Semitism, and vowing to bring back the borders of the old empire, restore the military-industrial complex, and give the 25 million Russians living in the “near abroad” of the former regions their human rights again.

In this dangerous and volatile mix, the Western media have become Zhirinovsky’s master and his slave, exposing layers of a dark and hidden past while feeding Zhirinovsky’s voracious appetite for exposure. His true origins are mysterious, and he has long been suspected of having K.G.B. ties. He was brought into politics when the highest levels of the old Communist regime registered his party illegally in 1991. He is the parliament’s leading provocateur, and it is in his interest that the country remain destabilized, fearful, and insecure.

Without a domestic program to speak of, this once obscure lawyer needs ever escalating acts of outrageousness to attract attention. He has threatened to “nuke” Japan and napalm “barbaric peoples” in the South of Russia. As soon as he won, Zhirinovsky began goon-buffoon tours of Europe, allying himself with neo-Nazis in Germany, reportedly attacking a hooker he picked up in Austria on Christmas Eve—which he denied—and, in Strasbourg last spring, spitting at French students who were protesting him.

In the Duma, the Russian parliament, Zhirinovsky not only charged that the candidates for speaker belonged in insane asylums but also, with his guards, beat up a defecting member of his party as well as a journalist who tried to intervene. The same day last April on which he signed an agreement of civic accord, promising not to attack the government, he told a group of students, “It’s just a piece of paper. Today we signed it, tomorrow we violate it.” Recently, at Moscow State University, he said that “the present government ought to be shot,” and he challenged all of Russia’s other presidential candidates to a sexual competition, claiming he could keep going for 12 hours while his opponents would be carried away to coronary wards. Such behavior does not go unnoticed. Zhirinovsky is currently mired on one side or the other of more than a dozen lawsuits. In June, the acting chief federal prosecutor formally asked that the immunity normally granted to deputies be dropped so that Zhirinovsky could be prosecuted for “warmongering” and fomenting ethnic strife.

As a candidate for Russia’s presidency in 1996, he often demands payment for interviews—up to $5,000 an hour. I, however, have refused to pay, so the world’s newest evil poster boy taunts me: “Take my clothes off in front of the world.”

“Only 8 percent of us is left. In 50 years only 2 percent of whites will remain.”

A week later certain documents are given to me by a dissident K.G.B. colonel that just might make good on his dare. But not yet. Not here. On this early-March morning in his run-down dacha outside of Moscow, where he retreats on weekends with a cadre of jackbooted skinhead guards and a young blonde spiritual adviser culled from a nearby Russian Orthodox monastery, Zhirinovsky is totally turned on by the presence of a Spiegel TV documentary crew. The Germans, who have paid, are preparing Ulrich Stein’s Portrait of Zhirinovsky, and the subject is outfitted in sweatband and jogging suit, doing shtick to scare.

“Pose me questions,” he commands, pounding his fist on the table. “Tell me some more lies.” I suddenly realize I am supposed to be the prop for the kitchen scene: See potential crypto-Nazi-nationalist Russian strongman on the rise tear into American reporter. One of the most disturbing aspects of Zhirinovsky is that he is such a complete camera animal, so clever and instinctive about personalizing the discontent of Russians today that he rarely has to go beyond quips and slogans to leave his stodgy opponents far behind. Swirling juice in a coffee cup, he says, “It’s not Pepsi-Cola. This drink is made from berries. Why do we need your Pepsi, hamburgers, or McDonald’s?” It is a theme he returns to again and again: democracy equals capitalist imports equals corruption of the Russian culture and soul.

And always the victimization is personalized. Millions of Russians are suffering, just as Zhirinovsky, the fatherless boy from Kazakhstan in the former Soviet Central Asia, has suffered all his life. That is the calculated message of his autobiography, Last Dash to the South: The author and the motherland are one. Mein Kampf comes to mind when Zhirinovsky cries, “You’re probably going to tell me my father was Jewish. I don’t have a drop of Jewish blood in me!” In fact, the Associated Press and CNN have since reported that his father’s name was Eidelshtein.

As if to prove that he is not Jewish, Zhirinovsky jumps up and summons his 23-year-old Bible instructor, Anastasia Sememova, who begins to read from the Old Testament. But Zhirinovsky, though he tries to align himself with the church, soon runs out of patience. “What does Moses in the desert have to do with the Orthodox Church? Nothing. . . . It’s all about Jews wandering around in the desert. . . . People are depressed when they leave our churches. People are crying. Healthy men steal and commit violence and the rest are crying because they read the Bible. Give me a different chapter.”

“I am sure he will be president,” Sememova tells me. “All the democracy forces discredited themselves. People don’t like them anymore. We can’t live in a democracy as it’s understood in America or Europe. People believe if a man has money he stole it. Five years ago it was a shameful thing not to know languages. Now the Russian people are giving up culture to pursue money. Our newspapers and TV don’t teach us to learn, they teach us how to make sex good, how to lie to somebody in a nice way—all the bad things of capitalism with Russian extremism.”

She dismisses Yeltsin as a drunk. “I was doing a Yeltsin interview during the last Gorbachev-Bush summit. He was standing a few feet away from me, and I smelled him. People talk about this all the time—how much Yeltsin drank today or yesterday.”

Stories about Yeltsin abound. Some will tell you that he mixes painkillers for a bad back with vodka and the results are disastrous. Others will say he is depressed or seriously ill. Few Russians I spoke with will ever forgive Yeltsin for firing on his own people last October in order to put down the Communist rebellion at the Russian parliament building and the state TV complex, where, it is believed, hundreds more died than the official body count of 147. “He has put a bloodstain in the center of this country and it will not wash out As long as he’s there, it’s there,” says Olivia Ward, the Moscow correspondent of The Toronto Star, who was caught in the cross fire.

It all adds up to a climate rampant with lawlessness and instability and a loss of faith in Boris Yeltsin that Zhirinovsky is only too happy to exploit “I have 10 serfs, but I need at least 60,” he jokes as one of the “young falcons” puts his shoes on for him. “Russians should not be slaves—Turks maybe, not Russians.” Zhirinovsky begins to spar with one of the older guards with a shaved head, “from counterintelligence—we’re all from counterintelligence.” The boxing scene is silly. Zhirinovsky is gasping for breath within two minutes. “I like to fall asleep while my bodyguards torture somebody in the night,” Zhirinovsky deadpans to the camera. Then he gratuitously attacks the former Soviet region of Uzbekistan. (It is a tenet of Zhirinovsky’s that all the swarthy non-Slavs who have inherited regions of the former empire that are rich in oil and natural resources are going to take it on the chin when he comes to power.) “Today, Uzbeks are in charge of a country built by Russians. Who the hell is Karimov?” he asks of Uzbekistan’s president. “He should be driving a camel, not a country.”

Then he unleashes on the Germans. It matters not that Zhirinovsky is quoted in a previous Spiegel TV report saying, “The only really consistently reliable partner is Germany.” Today he has decided to profess the opposite. “Kohl and Gorbachev—their names are going to be written in black paint in the history books. Gorbachev is already out, and Kohl will soon follow. Gorbachev was a traitor just like Vlasov [the World War II Russian general who went over to the Germans] was a traitor when we had a war with Hitler. Do not interfere in our life! Do not accept Gorbachev the Bolshevik!”

Now Zhirinovsky is off on another tirade, pacing around in his sleeveless white undershirt, talking tough to the big guys—the U.S. and Germany. “The world is on the edge of a war. If something happens in Russia, that’s where it will start. Everything here will come to an end, and the army will stage a coup. In order to feed a hungry and angry Russian population, we’ll have to expand. Where? I say south, others say west. We already have soldiers [in Europe]. Another 300,000 and we’ll remake Europe so it has Russian characteristics.

“We’ll stack German, Japanese, French, and American corpses like wood. We won’t invade you ourselves; we’ll send the Turks and the Arabs. That’s how we’ll destroy Svhite’ Europe. Then we’ll finish off the Arabs.”

The United States, of course, will be brought to heel in Zhirinovsky’s grand plan, because he has long believed America breeds plagues. “Everywhere there is war, there are Americans,” he told an audience of his Iraqi friends in Baghdad last year. “Wherever there are diseases, they come from the United States—AIDS, drunkenness, moral dedine, everything.” Today his message is one of U.S. capitulation. “The U.S. will experience a full assimilation of the Russian language and law, and the ruble will rule.” Russia, in this scenario, is being pushed to the brink by the rich nations that want it kept weak. “Do you know why poor people rebel? Because they are robbed! You all have warm, cozy houses. What do you expect of poor people? They’ll just take that house and live in it. You’re the ones who made us poor! You want us to leave this planet! We can’t take any more!”

“Wherever there are diseases, they come from the United States—AIDS, drunkenness, everything.”

Even in his hatreds, Zhirinovsky seems incapable of constancy. Some days he appears to despise Arabs even more than Jews; he is an equal-opportunity opportunist. “He is like a hysterical person; he allows himself complete freedom. Obviously some people find such a person convenient, because it’s easier to intimidate the world around them with such a person,” says Russian human-rights activist Sergei Grigoriants. “He is a person who could really throw a bomb.” Or is it all just an act? “His hysterias are well planned,” says former Yeltsin adviser Galina Starovoitova, who was trained as a psychologist. “He knows when to stop, when to start how to keep the public attention on his person. He speaks like Hitler, like a charismatic person, keeping the attention of the crowd on himself.”

“I’m sitting out here at the dacha, which belongs to them, the Communists and radical democrats, and they are just like a bunch of spiders in a can, alternately putting each other into prison and sitting at home waiting to be arrested,” Zhirinovsky continues. “I am waiting for nothing. I’m ascending higher and higher. I feel good. Yet so far our Russian compatriots don’t feel good at all. That’s why I cannot be completely happy. And I do my best to make it better for the majority of Russians, no matter how much I understand that it does not always seem realistic. That’s it,” he declares suddenly. “The tape is over. Let’s go to the cemetery.” Just like Madonna in herdocumentary, Zhirinovsky is going to visit his mother’s grave.

It is fashionable among the Moscow intelligentsia to dismiss Zhirinovsky as a lunatic egged on by the Western media. “He will become less and less important, because people will realize his magic is an evil one,” one of Yeltsin’s closest advisers tells me. “He is not civilized, and of course he has not got the moral qualities to be a leader.” President Yeltsin told Newsweek earlier this year that he does not consider Zhirinovsky a threat. But others do. Michael McFaul, a research associate at Stanford who was in Russia at the time of the elections last December, reports that some military districts ran “72 percent” for Zhirinovsky. Igor Serebriakov, a former army colonel who heads Fatherland, a military-information clearinghouse, estimates that Zhirinovsky got 50 percent of its vote, and says that many in Zhirinovsky’s party have extensive military backgrounds.

Zhirinovsky in his campaign made many promises to the military to improve its living conditions. He told me that he also has widespread support in the K.G.B. “Ninety percent of the officers in the K.G.B., police, and army are my supporters, and they help me,” he boasts. “Some of them went into banking structures or into banking. Others are in the state administration and help me from there. I always spoke about it—it’s no secret.” If Zhirinovsky comes to power, Serebriakov believes, he will sooner or later initiate a threat of force. “He will need a military conflict. He will not be able to put the country’s economy right; no one will be able to do this now. . . . But since Zhirinovsky will be unable to deliver the goods inside the country, he will want to take them away from somebody.”

Serebriakov makes a flat prediction: “Three months after Zhirinovsky comes to power, the world will face a threat of an active nuclear war in a way it has never done before.”

Some Russian vital statistics: Life expectancy for males born in 1993 is 59 years, down from 65 years in 1987. The birthrate dropped 15 percent between 1992 and 1993, and last year there were 800,000 more deaths than births. Suicides have increased 50 percent in the last four years. Rates of cancer, V.D., TB, typhus, and dysentery have also risen alarmingly.

Who is to blame for all this? The fact that only 55 percent or less of Russia’s eligible voters participated in the December elections—the figures are in dispute—which officially gave the L.D.P. 22.8 percent of the vote and elected 64 deputies from Zhirinovsky’s party to the Duma, shows that politicians are not held in high esteem.

“Life was different two years ago—I was a human being.” Dr. Valeray Belyakov, a young widower with a nine-year-old son, is the chief of a department of a rehabilitation hospital for children in Moscow. He cannot make ends meet on his salary of $33 a month, so he drives for people whenever he can. He also feels an acute loss of status. “If anybody told me five years ago I would be earning money like this to have a more or less normal life, I would have smacked them in the eye.” But what about these newfound freedoms? I ask. “Freedom for what?” he counters. “Freedom to buy a pornographic magazine?”

At a higher level, fights are raging all over the country among those bureaucrats who want to hang on to state property, those who want to privatize it, and those who simply want to seize it. For the new “capitalists” who are adept at the grab—the Russian Mafia, the former K.G.B., and Communist officials who know a good thing and use their f leverage to get it—the current wave of violence and lawlessness is beneficial.

According to this theory, they can take advantage of the chaos and grab now; then when they’ve gotten enough, they can reinstate an authoritarian regime to protect their newfound assets. “Zhirinovsky is a very convenient leader for them,” says Grigoriants. “It is clear that he will retain the principles of private property. All these people have obtained their private property and have no wish to see it turned back to the state. They just want again to add state power to the money they already have.”

“Zhirinovsky was financed by the K.G.B., not directly but by a chain of organizations.”

Meanwhile, all over Moscow there are markets now offering fruits and vegetables that were unheard-of a few years ago—bananas, strawberries. There are also other markets, some several blocks long, which consist of people lined up to sell one or two items: a chocolate bar, a can of olive oil, their shoes and clothes—whatever will fetch a few rubles. Part of the pain for many, though, is not only not being able to afford the new, plentiful goods but also witnessing the conspicuous consumption of the few who are getting rich while the rest in this highly educated culture are left behind. In my Moscow hotel, a hub of wheeling and dealing, there are boutiques selling gold-studded green alligator pimp shoes imported from Italy for $895. Only hard currency and credit cards are accepted—no rubles. An American dealer of luxury cars in Russia reports to me that business is “real good.” But when I ask the first woman I approach in a market if her life has changed in the last two years, she bursts into tears. Nadia is 58; she worked 40 years in a potato factory, her husband is an invalid, her monthly pension is worth $14—28,000 rubles in a market where beef (which few go near, because “it’s probably from Chernobyl”) sells for 3,500 a kilo. “It’s not life, it’s just existence.”

‘Wherever you point, there’s a Jew. The Jews should keep silent,” Zhirinovsky told a reporter in 1992. “A great many Jews are teachers, doctors, and lawyers. And the Russian people see all this—the high salaries the Jews get.” Zhirinovsky’s frequent anti-Semitic statements make rumors of his Jewish parentage—which he always vehemently denies—worth exploring.

Five months before Vladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky was born, on April 25, 1946, his mother’s marriage certificate shows, Aleksandra Pavlovna married Volf Isakovich Eidelshtein, a 38-year-old planner in a Soviet cooperative that manufactured clothes and shoes. He was officially listed as Jewish. Aleksandra Pavlovna was Russian. Pavlovna’s previous husband, Andrei Vasilyevich Zhirinovsky, had died of TB 19 months earlier. His death certificate notes that he had worked as the head of the forestry department of the Turkistan-Siberian railway. Files retrieved by Vanity Fair from the railroad archives reveal for the first time that Andrei Zhirinovsky was a lieutenant in the N.K.V.D., Russia’s internal police (a precursor of the K.G.B.), and a Communist Party member who rose to the level of head of a security detachment for the Leningrad railroad. He was later fired and sentenced to one year of “corrective labor.” In 1939 he ended up in Alma-Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan, as the head of the railroad’s construction-machinery supply unit. When Zhirinovsky died, he left his young wife with five children, aged 12 to 2.

Ironically, on the day of Aleksandra Pavlovna’s second wedding, records show, Eidelshtein’s younger brother, Aron Isakovich Eidelshtein, aged 34, also married. He too was employed in the forestry division of the railroad, as senior engineer. His handwritten C.V. from the railroad archives says that he was born in the Ukraine, near the Polish border, graduated in economics and law from Lvov University, and later was assigned to the timber department of the Turkistan-Siberian railroad. To complicate matters further, Volf Eidelshtein and his brother, Aron, both listed as their address the same flat where Aleksandra Pavlovna had lived with her first husband, Andrei Zhirinovsky.

The original surname on Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s birth certificate was Eidelshtein, but his father is identified only as “Volf”; the back of the certificate notes that there are “no documents for father.” Zhirinovsky has always maintained that his father died in an auto accident when he was three months old, but there is no record in Alma-Ata of the death of either a Volf Zhirinovsky or a Volf Eidelshtein. On the official housing registration that every Soviet citizen was required to have, young Vladimir was also surnamed Eidelshtein, with a specific passport number. But handwritten notations on the birth registration and a new entry on the housing ledger say that the name Eidelshtein was officially changed to Zhirinovsky in June 1964, when Vladimir was 18 and about to apply to the prestigious Institute for Oriental Languages at Moscow State University.

Indeed, the application for the name change, dated June 10, 1964, and signed “Eidelshtein,” has also been found, along with the record of a new passport number, which was issued within a week of the approved name change. The new passport is made out to “Vladimir Volfovich Zhirinovsky,” nationality: Russian.

In Last Dash to the South, Zhirinovsky tells a different tale of patrimony. “My mother was Russian … and my father was an ordinary legal adviser.” He also says his mother had been married previously to “a military man” who died, but he doesn’t give his last name. In fact, the father he claims for himself sounds like a Zhirinovsky-Eidelshtein combination. For example, he states that his father worked for the Turkistan-Siberian railway, just as his uncle Aron did, and that he was born in 1907, making him the same age as Volf Eidelshtein. At school the boy was known as Vladimir Andreyevich Zhirinovsky, the surname of his brothers and sisters. Vanity Fair has obtained Zhirinovsky’s high-school transcript. On it, the patronymic Andreyevich was changed to Volfovich on June 26, 1964, the day his diploma is dated. When the name change was made, in a handwriting different from that of the rest of the transcript, his grade in Russian was raised from a 3 to a 4. It would have been very hard to be admitted to the university of his choice with a 3 in Russian.

When I asked Zhirinovsky’s sister Luba, who is nearest in age to him, why both she and her brother had the same last name when their fathers were different, she said, “Our fathers were brothers.” Yet neither she nor her eldest brother, Aleksandr, a retired army colonel 14 years older than Vladimir, with whom I also spoke, could recall a single thing about their younger brother’s father, which seems peculiar if he was an uncle who married their mother.

Zhirinovsky denies that he ever changed his name, and his running mate in 1991, Andrei Zavidia, claims that he disliked even the name Zhirinovsky. According to Zavidia, Zhirinovsky told him, “If my surname were Ivanov, I’d have been president long ago.” The L.D.P. press secretary charges that the documents were manufactured as part of a plot by the special services in Kazakhstan to damage Zhirinovsky. But the Associated Press stringer in Alma-Ata, Nick Moore, who broke the original story on assignment for CNN, is convinced that the four different sets of documents he uncovered with a Russian journalist are real: “I have no doubts about their authenticity, because of the numbers of overlapping proofs.”

In his book, Zhirinovsky dwells at length on his miserable childhood in one room of a communal apartment, the unloved youngest who got nothing.

Worse, he had to share his exhausted mother, who worked in a cafeteria, with her much younger lover, a poverty-stricken student who moved in for 12 years and got more food and attention than Vladimir did. Cold and poor, he never had any toys. His teachers picked on him; nobody celebrated his birthday until he was 16. “Society could offer me nothing,” he writes.

“He didn’t seem a sad boy,” his sister Luba contradicts. She does say that he missed having a father very much. “When he would see boys being led by the hand of their fathers, he would say, ‘Why don’t I have this?’ ” By 12, his sister says, Zhirinovsky had memorized the names of all the Soviet generals, and early on, he writes, “I intuitively saw that I was obviously destined for big4eague politics. And this came to pass.”

After graduating from high school, Zhirinovsky set out for Moscow. Graduates of the Institute for Oriental Languages say that it would have been very difficult to be admitted to the elite school as a Jew. As it was, his highschool grades were good but not outstanding. “At this college it is impossible to study unless one is approved by the K.G.B.,” says a former K.G.B. agent, and studying there would automatically mean that the K.G.B. kept a file on him. He was admitted to study Turkish. (He also speaks English, French, and German, after a fashion.)

Although he was a young Communist League organizer during his last years at college, Zhirinovsky was crushed that he was not chosen to work abroad by his school, which reportedly had a K.G.B. mentor in residence. He says he made some “hard-hitting speeches” and was considered “politically unreliable.” He did manage, though, to get permission in 1969 to go to Turkey for a year. “I am 100 percent certain it was unfeasible to have one’s trip to a NATO country approved in 1969 unless one was a state-security employee,” a former schoolmate told a Moscow newspaper.

In Turkey, Zhirinovsky went to jail for “conducting Communist propaganda”—purportedly a bogus charge brought for giving out Soviet pins to Turkish kids. He was sent home after eight months. This incident, the first of several professional miscues, would cast a shadow over his intelligence career. After graduating with top honors—awarded only to politically reliable students—he joined the army as an officer, and was assigned to what sounds like classic propaganda and intelligence work: to deliver “lectures among the troops,” write pamphlets, and study the Near East. He was stationed in the Republic of Georgia, at the headquarters of the Transcaucasus Military District Staff Political Directorate.

“That he was watched, that people informed on him to the K.G.B., I am 100 percent certain,” says former K.G.B. lieutenant colonel Aleksandr Kichikhin, who has spent considerable time investigating Zhirinovsky since leaving the secret police. “I personally have no doubt that he was being used. Look at it in terms of the kinds of jobs he got—the Transcaucasus district military headquarters. To a professional, it is clear that that was a division of the main intelligence administration. He wasn’t just an agent, he was an officer there…. Military intelligence is a special service, and they cooperate with die K.G.B. Probably all the time from college on he was in contact with the K.G.B. It’s impossible to break off with this organization; they never leave you alone.”

Zhirinovsky’s wife, Galina, a biologist, says the two met in 1967 at a vacation camp for students near the Black Sea, and were married six weeks after he joined the army, in 1971. She is under the impression that a courtship took place which resulted in marriage. But Zhirinovsky in his book laments that “during these student years I really had no girl. I badly wanted to fall in love with someone and date her, but it did not work out.” Until then he never mentions his wife’s name, or reveals that he married her at all, except to complain suddenly in the middle of a paragraph on army life, “My wife refused to come with me.” She stayed in Moscow to work on her Ph.D. They had one son, who now studies law.

He would shave his head and appear wearing a military shirt, speaking “in an excited manner.”

Before beginning his rapid rise in politics in 1990, Zhirinovsky held three different jobs, in which he became known as an outspoken eccentric and a witty, harmless crazy who often landed in hot water. After he left the army, he got a job with the Soviet Peace Committee, dealing with foreigners who came to Moscow with various delegations. “Of course it was a K.G.B. front, no doubt about that,” says Kichikhin.

Zhirinovsky studied law at night and earned his degree, which led him to a new job. “For several years all went well,” relates Yevgeny Koulichev, his immediate boss at Inyurkollegiya, a state legal agency of 50 lawyers, where he practiced law from 1975 to 1983. “I can’t put my finger on it exactly, but in the last two or three years of his stay here he began to change. It started when he applied to join the Communist Party and was turned down.” Zhirinovsky vehemently denies that he ever applied for party membership, but Koulichev insists he did. “I saw the application.” He explains that Zhirinovsky was rejected on the basis of his character and certain statements he had made. Both Koulichev and another lawyer there, Nadia Kozlovskaya, recall episodes of his bizarre behavior: a couple of times a year, for example, Zhirinovsky would shave his head and suddenly appear at the office completely bald and wearing a military shirt, speaking “in an excited manner.” His co-workers did not buy such utterances as “We Russians are surrounded on all sides by Muslim peoples: Azerbaijanians, Tartars. They are breeding too fast, and they may overwhelm us eventually.” These lawyers were stunned, in 1993, when what they had heard years before at the office became a winning political campaign. Says Kozlovskaya, “I was very sorry when I found out he won. I thought he was unbalanced.”

In the late 70s, I was told by several sources, Zhirinovsky became involved with another woman. They reportedly continued the affair for a number of years, and many assumed they were married. “I was very surprised when I saw him on TV during the recent campaign with his first wife again,” says Kozlovskaya. Mrs. Zhirinovsky told me stiffly, “This is the only marriage.”

Zhirinovsky was reportedly furious at being denied party membership, for that meant that he was also cut off from career advancement. According to Koulichev, he began writing nasty letters, some signed, some anonymous but easily traced to him, to the district party committee and Justice Ministry, “expressing indignation at not being accepted . . . and saying there were drinking parties held in the office—perverted things.” The letters were immediately sent back to the law office’s management.

Eventually, Zhirinovsky was forced out of Inyurkollegiya, but what got him fired had nothing to do with politics. He accepted what was considered to be an improper gift. Koulichev explains that when clients inherited hard currency from abroad it was possible to turn the money into vacation passes. One client gave one or two of these to Zhirinovsky. “In those days it was called a bribe,” Koulichev says. “He refused to consider it a bribe. He returned the passes, but he was not seen as somebody deserving full confidence. They called him in and said, ‘We’ll offer to let you resign.’ ” Zhirinovsky has denied doing anything improper.

Mir, a publishing concern with 600 employees, many of whom had served in the military or K.G.B., needed someone who knew foreign languages to do contracts and international copyrights, and inexplicably Inyurkollegiya gave Zhirinovsky a glowing recommendation. He earned less money than he had before, and he didn’t know much about copyrights, so he cast himself as the defender of the little guy, a vociferous anti-Communist advocating free lunches and a distribution of profits to employees. At Mir, Zhirinovsky constantly came on to women, who rebuffed his advances, and he complained to his superior, Vladimir Kartsev, that he was strapped from having to pay child support for his son. “He used this argument when he tried to get higher pay,” says Kartsev. Zhirinovsky no longer shaved his head or wore military shirts to the office, but Kartsev remembers occasions when he became extremely agitated and seemed to foam at the mouth while speaking.

In 1985, Zhirinovsky caused a scandal by standing up at what was supposed to be the usual rubberstamp election of a deputy from the publishing house to the local party and insisting that they cancel the meeting and follow the written rules, which guaranteed “free elections.” Kartsev remembers Zhirinovsky’s saying, “I think you should elect me as deputy.” In the end, the flabbergasted party chiefs canceled the election.

In 1987, Zhirinovsky offered himself again to be Mir’s representative to a district council in Moscow, but the rules were rewritten to keep him out. At the same time, a secret letter arrived from Inyurkollegiya detailing why Zhirinovsky had had to resign. Nevertheless, in 1988, Zhirinovsky campaigned to be a member of a new employees’ council, and just as he did in last December’s national campaign, he mounted a populist platform: Mir should forget about publishing scientific and technical texts and concentrate on moneymaking books, the profits from which would be distributed to the employees. Kartsev implored his workers, ” ‘I ask you as director, believe me: don’t put Zhirinovsky on the list, because he’s unpredictable and a demagogue.’ They followed my advice, and I considered it a moral victory.”

“You’re going to tell me my father was Jewish. I don’t have a drop of Jewish blood in me!”

By 1989, when Kartsev was leaving his post to work at the U.N., Zhirinovsky was already out in Moscow’s Pushkin Square for endless hours at night, honing his clever rhetorical skills at street rallies, and by day he was joining wildly disparate organizations—a real-life combination of Zelig and Sammy Glick. He was elected to the board of a Jewish cultural organization, Shalom, which had been created as a K.G.B. front (Zhirinovsky has denied being a member). At the same time, he spoke at a rally for the rightwing, anti-Semitic Pamyat group and also joined the first radical democratic party, the Democratic Union.

Ambitious and hungry, Zhirinovsky went anywhere anyone would have him, and he soon got involved with an emerging group of “dwarf parties” called the Centrist Bloc. It was then, according to reports from those who knew him, that his thinking began to take on its ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic colorations. It later emerged that part of this bloc had ties with high officials of the Soviet regime who were trolling for people they could manipulate.

In 1990, Zhirinovsky sought one last time to get elected to something at Mir: he ran for Kartsev’s job as director. But he garnered only a few dozen votes, so he decided to leave. One year later, Vladimir Zhirinovsky received six million votes and came in third for the presidency of Russia.

‘Waiter, waiter! Give me some water. We don’t need a menu. Just tell us what you have. Close the menu—all I need is a salad. One big salad for all of us. Do you have lobster soup or something like that? Actually, everyone will have the same.” Vladimir Zhirinovsky has just ordered lunch for the table, including me, the hostess, without consulting anyone. He has shown up at the posh Metropol Hotel near Red Square with two aides and three bodyguards.

“Why do you have so many guards?” I ask.

“We’re a new political organization; we are in the opposition. The country is at war; chaos has descended all over the place.” But mostly, Zhirinovsky concedes, his guards are there to keep his fans from mobbing him. “That’s how I won this victory, because millions of people recognized their own living conditions, and it was the first time they heard a person speak openly about their lives in a way they have always wanted to, but were afraid.” He wants to marry his early victimization with that of the people, and says that all Russians are triple victims today—of the previous regime, of strained relations between ethnic groups, and of the economic crisis, “where the thieves and the crooks have won.” As an example, Zhirinovsky attacks the expensive restaurant we’re in. “In this hall everybody is either a spy or a thief. A normal person cannot be in here.”

“Is there a way to get rid of them?”

“Today, yes. In about 20 years, no. So far, you don’t have many of them. The max is 2 or 3 percent of the population: they control places like this. They steal money, sit in banks, and come here to spend the money on food.” As a result, Zhirinovsky says, the people feel robbed, not only by the Mafia but also by the “international friends who cheered perestroika, which turned out to be a tragedy.” Why, I ask. “Because we had a country with its economy, its health care, its education—it might not have been the best, but at least it was available to everyone.” Zhirinovsky stops mid-thought. “I said bring what we ordered quickly, put it down here, and that’s it!” he tells the waiter.

I try again. “Do you feel America is somehow responsible for this?”

“Of course. America, Germany, France, Britain, Japan—everybody benefits from knocking Russia out of their list of competitors and adversaries. But they are disappointed now. They don’t know what to do. We were richer then; we’re poorer now, which means we’re more angry.”

“Do you feel there is much to criticize in American society?”

“No. Live as you wish. We do not want your culture forced on us. . . . All you give us is rubbish horror movies all the time. We don’t need your cowboys, violence, and cigarettes.” The American ads Zhirinovsky sees on Russian TV gall him the most. “You’re showing us your resorts, and people here do not have the money to bury their relatives properly.”

“What would you do your first 100 days as president?”

“We’ve already implemented our goals from our election campaign. We promised to change foreign policy, and we have started changing it. We promised political amnesty, and we did it. We promised to recommission the military-industrial complex, and we will do it. . . . We are in favor of the market. But let’s trade. The Americans deceived us. They said, ‘You dissolve the Warsaw Pact and we’ll dissolve NATO.’ We have dissolved the Warsaw Pact and NATO is still there. They say, ‘Take the troops out of Germany.’ We do. The American troops are still there. They say, ‘Reduce the production of weapons and we’ll do the same.’ We have. They are not reducing anything.”

I try to advance another question, but Zhirinovsky is paying no attention. He has caught one of his guards lighting up. “Who’s smoking here?” he thunders. “Some aides you are! You better take cigarettes away from people who smoke in front of me instead of smoking yourselves.”

Perhaps the idea of restoring the czarist borders attracts him, I suggest, because he behaves like a feudal baron. “It’s impossible,” Zhirinovsky counters. “How are we going to get Alaska back? Finland is better. Ukraine, the Baltics, the Caucasus—this is all Russia.” He is unconcerned that these now independent regions have their own nuclear weapons and may not want to come back to the old Soviet fold. “Those are ournuclear weapons! They do not know how to use them. We have the button. They cannot press it without us. And we made them in such a way that they will explode in their hands, because they don’t know how to use them.”

Oh, no. The waiter is back again. “What is that crap he’s giving us?” Zhirinovsky demands as the waiter attempts to pour vinaigrette on his salad. “Vinegar! I don’t eat vinegar.” He grabs his aide’s plate and switches with him. “Here, you eat this.”

“Should the U.S. feel threatened if you were president?”

“No way,” Zhirinovsky purrs. “There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

Oh, but there is if Zhirinovsky is even half serious about the ideas of expansion he professes in his book—a world where the North dominates the South instead of the usual East-West conflict. “North-South conflicts are more reliable and less dangerous,” he says. I haul out a map for him to illustrate. He’s delighted. “I do like maps very much. I’m a map man. O.K., here we have North America, which should be taking care of Latin America. Plenty of ocean around, very convenient. A perfect case of North-South relationship.” (Where does that leave Cuba? Zhirinovsky concedes, “It was the Communists’ most severe mistake, to get entangled in Cuba. We absolutely did not need it.”) “Western Europe’s former colonies are all in Africa. Let Western Europe take care of it. Let China and Japan take care of Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia, and New Zealand. And let Russia’s sphere of influence be three countries: Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan. We give you a lot more: the whole continent of Africa goes to the small territory of Western Europe; North America will similarly get a big continent, but we need less than anybody else, just three little countries. We get the smallest lot.”

Of course, this is in addition to re-establishing the U.S.S.R. with its former boundaries. “So how do you get the Soviet Union back together?”

“You trade with them at international prices and not give them our military help. This way their independence will pop like a balloon in four months. Like, if we take our divisions out of Tajikistan, in one month there will be no Tajikistan. In another two months there will be no Uzbekistan. They’ll destroy each other. If we stop helping the Azerbaijanians, the Armenians will destroy them. And the Armenians will also help the Kurds and blow up Turkey.”

Neat. “What about the Russians in those territories?”

“The Russian population leaves with the Russian army.”

“And the U.S. and Russia should cooperate in terms of preserving the white people?” I ask.

“Yes, of course,” Zhirinovsky responds without missing a beat. “Only percent of us is left. But the colored population multiplies extremely fast. In 50 years only 2 percent of whites will remain. We’ll be stomped down ethnographically. We must join our efforts. White Americans and white European Russia, that’s how you get the white North America, Europe, Russia. And all the colored down below.

“There are 1 billion, 200 million Chinese. And we on the territory of Omsk to Vladivostok [the vast region of Siberia] have only 22 million people. … And they are very fond of mixed marriages, but that will be the end of the Russians. Neither the Americans nor the Europeans have this danger. But we have enemies everywhere. Today the Chinese have already penetrated the Russian Far East. There are getting to be more and more of them, and if they are not stopped, they will come just as traders, and you’ll have many more of them than Russians. They will open Chinese schools, they’ll hire Russians, they’ll make them speak Chinese, and they will peacefully conquer Russia’s Far East.”

I ask Zhirinovsky if there are any world leaders he admires. “Nobody. There is no such person. [There is no one] to compare with in Europe or the U.S. You have a different life. You have Clinton playing the saxophone. If Yeltsin plays the balalaika here, everybody would say he is crazy.” Zhirinovsky says Bill Clinton is “a normal, typical American president,” while Yeltsin is merely passing through. “He’s our president. We’re enduring him as of right now. Once he resigns, we will struggle for the victory. In the meantime, he is the president and the seat is occupied.” Zhirinovsky blithely predicts, however, that “there will be a new government” by fall.

“That means Yeltsin will not be there?” I ask.

“The [Cabinet of ministers] may go. The president may stay. I’m talking about the government. He can continue being president and make it until the end of his term, once there is a strong chairman of the government.”

“Do you mean you would be a minister of the government?” I press.

“We’ll wait and see. Yes, it’s possible to take one of the power ministries—Foreign Affairs, Defense, Interior, State Security—these four. I want to be one of the power ministers.”

Toward the end of the meal I ask, “Is it true that the only person you’ve ever loved is your mother?”

“All the love a human is capable of I gave to her,” Zhirinovsky says, “because of my father, because of everything. By the way, no matter who my father was, he died when I was three months old, so he could not have had any influence.”

“Why are you so open about sex?” I ask. It seems peculiar, for a Russian politician, that in his book Zhirinovsky tells the reader about his first awkward moments trying to get a girl to sleep with him; it’s part of his victim pattern that he failed. He also admits he never loved his wife or had much lasting affection for his son.

“What should I hide? This was always a closed topic. The Communists in 1926 announced this to be a closed topic—no sex, and that’s it—and it still affects people today. For decades, inner sexual suffering—nothing was written about it in popular literature or shown on television. I was the one who talked about it in front of the whole country.”

“But doesn’t it bother your wife and family to hear you say that you never loved them?”

“Of course they reproach me for this. It’s an unpleasant thing to hear, especially for a woman. [Mrs. Zhirinovsky will later make it clear to me that the whole thing was a mistake: “They edited him a little.”] What woman would like to hear such a thing? But it’s much better than to hide feelings, like some others do. With this sincerity I want to bring my voters yet closer to me. They find this extreme honesty attractive in me. They understand that I will not cheat them on something big. I could pretend to be happy and satisfied, but they would not like it, because they would understand we have never been a truly happy and satisfied people.”

“Yeltsin has put a bloodstain in the center of this country and it will not wash out.”

As usual with Zhirinovsky, there is a method to the madness. “So you and the state are one almost?”

“Through the expression of the majority, because the majority wants a new Russia today. And this is my wish as well. So there is a match of desires, and that’s how I achieve success.”

Stop Yeltsin. Split the vote. Pretend to the world that we are no longer a repressive, one-party dictatorship. Maintain control. That is the message garnered from secret Communist Party documents drafted at the time of Zhirinovsky’s rise and obtained by Vanity Fair. Internally, the men who ruled Russia were brutally frank about the party’s impending demise, and they needed a pawn. From the beginning of Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s political career, the danger has been not only his chilling philosophy and crudely amoral behavior but also the gathering evidence that he is a tool backed by a sophisticated conspiracy of forces out to defeat democracy.

“Zhirinovsky was financed by the K.G.B., not directly but by a chain of organizations. He was also financed by the Communist Party,” charges Aleksandr Kichikhin. For nearly 20 years a lieutenant colonel in the prestigious Fifth Department of the K.G.B., the 44-year-old Kichikhin infiltrated political groups. In 1991, Kichikhin, who says that by the time of perestroika in the mid-80s the K.G.B. was virtually running the country, was sacked as a whistle-blower. He went to court and won the right to be reinstated, but his return was blocked within the agency. Instead, after the aborted coup of August 1991 against Gorbachev, in which Zhirinovsky sided with the hard-line Communists, Kichikhin became a special investigator for the parliamentary commission set up in September 1991 to determine how the coup happened. For several months he had extensive access to top-secret Communist Party archives and Justice Ministry files, which he copied once he realized that it was becoming too embarrassing for the government to continue the investigation. Too many people had participated in the coup. The investigation ended in December 1991.

Kichikhin subsequently made part of his material available to the Russian magazine Ogonyek, which published a detailed expose in 1992 of how Zhirinovsky submitted false data—fake names, forgeries, names without addresses—to the Justice Ministry, which in 1991 blatantly and illegally registered his Liberal Democratic Party anyway, after Gorbachev’s justice minister, Sergei Lushchikov, intervened. Following a news conference held by Kichikhin, the ministry was forced to nullify the registration and re-register the L.D.P. legally in November 1992. The problem, he says, is that he found that several other parties were also fraudulently registered, and that had his investigation continued, it would have led to the conclusion that “Yeltsin’s election was illegal, because all the candidates were registered illegally.”

Kichikhin has never shared his material with a Western journalist before. I took the documents he gave me to the librarian of Congress, noted Russian scholar James Billington, who told me he found the material “generally credible.” Billington himself had observed Zhirinovsky up close shortly after the August ’91 coup, and when I told him that my reporting showed that Zhirinovsky was a front man for others, he said, “That’s what the best-informed people I know in Moscow tell me.”

“Being a deputy of the U.S.S.R. Supreme Soviet,” said Galina Starovoitova, one of Russia’s most prominent female politicians, “I saw the ease with which Zhirinovsky penetrated all the Kremlin offices to which even the deputies did not have much of an access, how he communicated with aides and advisers to Anatoli Lukianov [head of the administration-and-organization department of the Central Committee], who relied on the K.G.B.” Starovoitova stated this at a conference on the K.G.B. in May. “I also know from witnesses that Gorbachev had instructed [then head of the K.G.B. Vladimir] Kruchkov to create a party which would oppose” the growing democratic opposition, whose most compelling figure was Yeltsin.

Starovoitova said that the Communist bosses knew that they would eventually have to give up Article Six of the Soviet Constitution, which guaranteed the party a monopoly of power. “So a rather clever move was thought up,” she said, to create an alternative party, “to demonstrate the country’s already existing political pluralism to the outside world, to demonstrate a liberal democratic party.”

Recently, in Washington, Starovoitova, who is writing a book on the subject, revealed to me what has not been known up to now: that it was Gorbachev’s close ally and politburo member Aleksandr Yakovlev, who is now the head of the larger of Russia’s two state television channels, who told her he was present in September 1989 when K.G.B. head Kruchkov approached Gorbachev during a dinner break in one of the sessions of the Central Committee and told him, “Mikhail Sergeyevich, we are working at your task now. We are selecting the leaders for this new political party.” Boris Oleinik, who once chaired the Supreme Soviet’s commission on new parties, says, “Of course Gorbachev knew about Zhirinovsky and his party. It had to be done with his permission.”

Kichikhin says he was told that Zhirinovsky had several personal meetings with Kruchkov between January and June of 1991—”My colleagues joked he wore a hole in Kruchkov’s carpet”—and his documents back up Starovoitova’s claims. According to these papers, in 1990 the Communists outlined a strategy to convince the Russian people: “If we don’t stop the democrats, we will be faced with the horrors of civil war, famine, and Fascist dictatorship.” In these papers, the Liberal Democratic Party is No. 2 on the list of the “associations we should support.” In August 1991, a document Kichikhin provided shows, the Communist Party of Lithuania was told to pay Zhirinovsky’s expenses during his visit there. (The trip was canceled because of the 1991 coup.)

“Zhirinovsky was created for the presidential elections of 1991, aiming at the marginal electorate,” says Konstantin Boravoy, a wealthy politician and founder of the Moscow commodities exchange. If the marginal electorate was the goal, it wouldn’t matter if their man was not always rational.

“I asked Yakovlev why the K.G.B. selected a candidate who was half Jewish, who could be so easily compromised,” Starovoitova tells me. “Yakovlev said it was done because the K.G.B. wanted to have control and be able to blackmail him. They did not know he would become so disobedient.”

“I used him like a rooster to peck through and knock down a wall and go up, up,” says businessman Andrei Zavidia, who had close ties to the former regime and ran for vice president with Zhirinovsky in 1991 but has now broken with him. “He’s a fighter, afraid of nothing. He’s a scoundrel who attracts attention. He creates scandal, and at that time it was very important to get into the political scene with scandal. We used him. It was his freedom of speech, his manner of speech, but it was my money and my contacts.”

Gorbachev has denied that he had anything to do with the rise of Zhirinovsky, but he told a Russian newspaper last January that he had received information that the “Zhirinovsky phenomenon” was bom within the walls of the K.G.B.

Kichikhin’s documents show that Zavidia had a three-million-ruble contract with the business office of the old Communist Party just before the 1991 election campaign, and that this money could be used for any “purposes permitted by the company’s charter.” Was the money ever transferred, and was it used to finance Zhirinovsky’s rise? Kichikhin believes it was. But Zavidia denies that the contract was ever carried out, and admits only that he gave Zhirinovsky 26,000 rubles for his platform to be printed. It was printed by the Communist Party press in the same format as the Communist Party’s. Zavidia adds, “Zhirinovsky asked [K.G.B. head] Kruchkov to help him during the campaign by giving him office space.”

Between the elections of 1991 and 1993, however, the country experienced a sea change, and Zhirinovsky, with the aid of shrewd advisers, sought to build a national party; he has consistently been the only major politician who tries to appeal to youth, with a heavy-metal music store, for example, right in his party’s ramshackle headquarters. Meanwhile, Kruchkov, who had allegedly helped Zhirinovsky, was in jail for having taken part in plotting the coup of ’91, and droves of officers had left the now discredited K.G.B. For many of the most successful, this meant that state property had simply been transferred, and the lucky nomenklatura wound up in control of some of Moscow’s largest banks.

Indeed, Kichikhin gave me a series of startling top-secret documents detailing the Communist Party’s plans to transfer vast economic reserves into the marketplace. One month before the August 1991 coup, for example, a resolution was adopted—and a copy was sent to Gorbachev—which authorized the party to start sending its capital out into “commercial entities,” which would issue stock to “party committees.” An earlier memo stated, “Our ultimate goal, along with commercializing our existing property, would be to establish an ‘invisible’ party economic structure which would employ a very limited number of persons.” The memo advocated learning “how to wheel and deal with the best of them” and establishing banks with the party’s hard-currency reserves. Interestingly, Kichikhin also affirms that the operation of smuggling the Communist Party’s assets was conducted through the K.G.B.

“In 1991 the K.G.B. was very active in setting up financial groups,” says Boravoy. “The first several thousand joint ventures were set up in such a way that permission was needed from the K.G.B. for one to be appointed to the post of top manager.”

It is some of these very financial groups that many believe bankrolled Zhirinovsky’s campaign. Boravoy, who owns a media empire and is one of the wealthiest businessmen in Russia, says that several of these groups gave Zhirinovsky money, but “no more than $200,000 to $300,000.” “The people who did finance the campaign do not care to reveal their identities at this point,” says Zhirinovsky’s former campaign manager Viktor Kobelev, who has split from Zhirinovsky because of his uncontrollable behavior.

He says they too are disillusioned with Zhirinovsky now because of his antics.

“I am telling you that the entire campaign was financed by three persons.

Three Russian persons, three regular guys. Minus the debt that remained of 60 to 80 million rubles.”

Kobelev, who says that Zhirinovsky “is capable of taking [money] from anyone,” also freely admits that the way to get business done during a campaign is to pay bribes every step of the way. For example, many wondered how Zhirinovsky was able to appear on TV just before the election as a guest on the Dmitri Dibrov program. “Thirty thousand dollars in cash was paid to somebody at the station. The money came from a friend of mine,” Kobelev reveals. He says that in order to avoid ponderous government banking procedures people stuff their “pockets with cash to pay everybody on the spot. . . . You see, all things in the country are run on commercial principles these days.”

In June of this year, details of a fascinating letter Zhirinovsky had written to Russian prime minister Viktor Chernomyrdin surfaced in the Moscow News. Zhirinovsky baldly requested that the prime minister intervene with the central bank to save Zhirinovsky and the L.D.P’s deposits of about $1 million in a failing Russian bank. Zhirinovsky listed his assets in dollars, deutsche marks, and rubles. In January, Zhirinovsky had also opened a personal account of 20,000 deutsche marks, but, according to the paper, bank experts said “they

believe the L.D.R chairman himself was the real owner of all the money,” and that large sums of foreign currency had begun to be deposited in cash in Zhirinovsky’s accounts the previous fall. Anyone who wants to join the L.D.P. is requested to pay 1 percent of his or her monthly salary as dues and to send the money directly to Vladimir Zhirinovsky. His sister and brother control all the party’s money.

Few in Moscow today who have seriously studied Zhirinovsky believe that he is his own man, and now, when Boris Yeltsin seems to have lost the moral authority to govern—his administration appears more in the traditional mold of Communism, intent on controlling the apparatus of the state rather than on capturing popular support—it is not inconceivable that Zhirinovsky could seize the reins of power. Many believe that the whole country is up for grabs. “It’s a very cynical situation,” says Boravoy. “If it’s possible to have presidential decrees prepared here for money, if one pays good money, it’s possible to bribe the main intelligence administration, foreign intelligence, and the K.G.B. There’s a situation of disillusionment now. They worked for the sake of ideology; they have been betrayed by the people, by the president.”

“The moment Zhirinovsky soars to a top post, he will be replaced with a real Fascist.”

Boravoy gave me an interview the day after he miraculously escaped death in a firebomb attempt on his car. Boravoy maintains his own intelligence operation, and his experts have come to the conclusion that Zhirinovsky is backed by the main intelligence agency, the G.R.U. Boravoy says that intelligence experts advised Zhirinovsky on themes for the campaign and told him to follow the example of Hitler and the Weimar Republic. Former campaign manager Kobelev says that Zhirinovsky advisers “have a kind of mania for counterintelligence and the K.G.B.”

“The Liberal Democratic Party is not as it’s been portrayed in the media—a party for the lower classes and society’s dropouts,” maintains sociologist Dr. Mikhail Savan of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He has known Zhirinovsky for 10 years and has conducted two polls of the party’s leadership. His data show party membership to be made up of 40 percent technical people and approximately 10 percent each of scientists, students, workers, and entrepreneurs. “It’s obvious he has a very skilled team working with him. In general they are representatives of an intellectual elite who have definite aims in using him.” A Russian paper, Segodnya, which is owned by the Most bank, allegedly populated by former K.G.B. officials, published a list of Zhirinovsky’s “shadow Cabinet” shortly after last December’s elections. The Cabinet contains a former employee of Mir and from 20 to 40 others, a number of whom worked in the milii tary space industry, in counterin[ telligence, and on secret projects. [ “He’s exploiting people’s memories of the past,” says Savan, “and he’s exploiting the military industrial complex. This is a strong political movement. This is what should be of more interest today than the figure of Zhirinovsky, because, according to the laws of politics, the movement will have its own logic of development no matter how Zhirinovsky puts his personality on it”

“The moment he soars to a top post, his origins will be remembered and he will be discarded and replaced with a real Fascist behind his back,” says Tankred Golenpolski, who edits a Jewish newspaper in Moscow. “That is the scary part.”

The final irony, of course, is that Zhirinovsky may not have won at all. Last May analysts hired by Yeltsin’s administration to study the election said that large-scale vote rigging added a staggering six million fraudulent ballots to the results, that legal balloting was below 50 percent, and that technically the referendum on the new constitution did not have the percentage needed to pass. This big story has essentially been ignored—especially by Yeltsin—and the leader of the group fired. Apparently, provisional functionaries, seeking to protect their power, stuffed the ballot boxes. Fearing they would be caught if they gave the votes to the party heavily favored to win, Yeltsin’s Russia’s Choice Party, they threw their fraudulent votes to Zhirinovsky and other marginal parties such as Women of Russia. But knowing that now is small comfort. It’s too late. Frankenstein lives.

No Comments