Vanity Fair – January 1997

As leader of Sinn Fein, the political arm of the Irish Republican Army, Gerry Adams is Northern Ireland’s most controversial politician, a hero to some, a murderer to others. MAUREEN ORTH follows his dangerous, charismatic high-wire act from Belfast to London to Washington as Adams tires to turn his people from terror to peace.

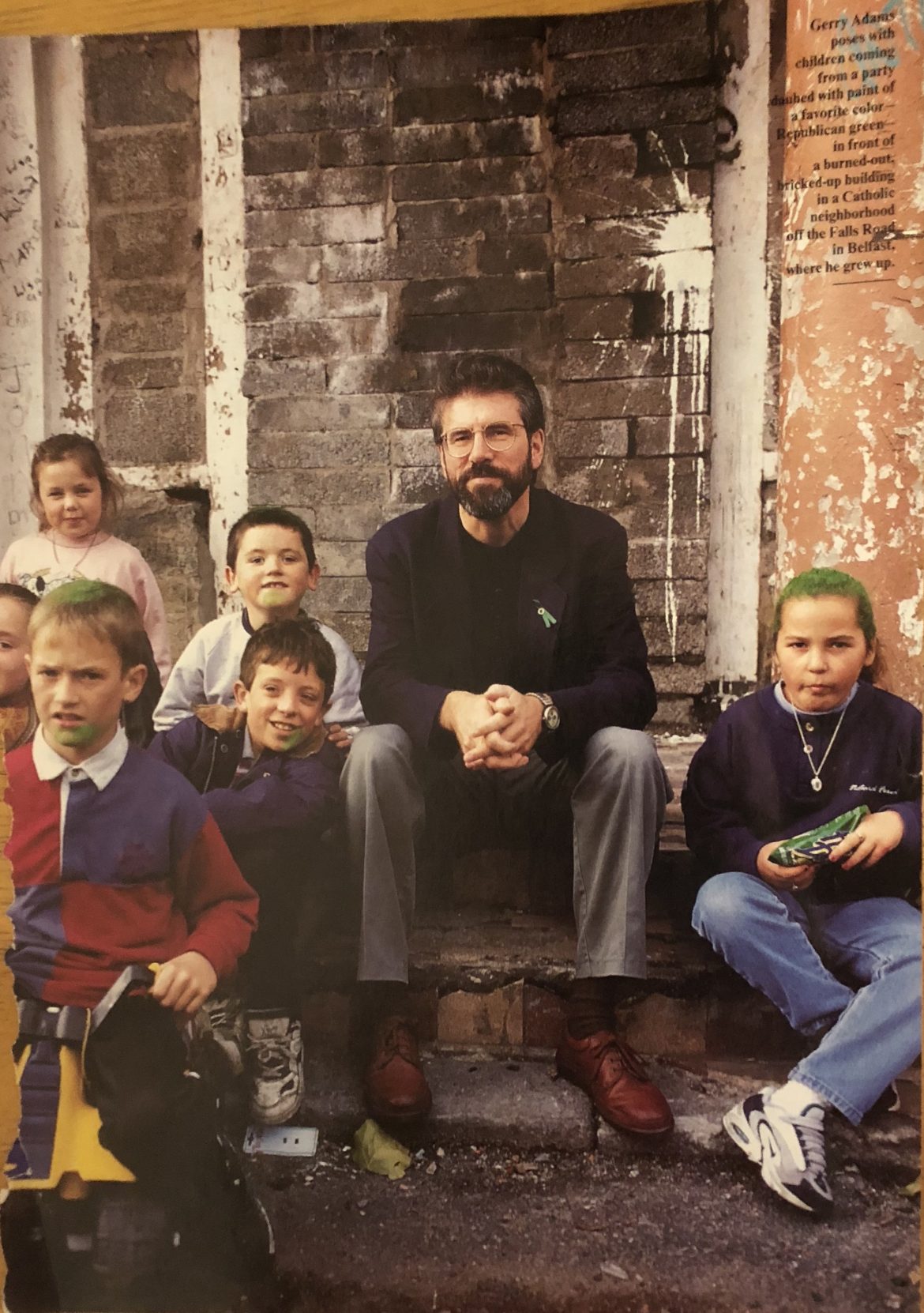

‘Did youse see the wee fox?” Gerry Adams inquires gently of two little “boggers” who live at the top of Black Mountain, a rural area above the West Belfast neighborhood where he grew up. Shyly they ask when the next march is. “Our granny’s name?” and recognizes it instantly. A key to the adoration of Adams in his home territory is how close he keeps to his base, how – despite the fact that he strides the world’s stage – he never forgets to high-five a kid such as eight-year-old Eamon in his dirty Lion King T-shirt, or to send regards to his granny. “Yeats said that too long a sacrifice makes a stone of the heart. I don’t think it’s necessarily true.” Adams tells me, “If you become detached from the base, then I think you’re in trouble. You always have to bear in mind what this is about. It’s about people.” After all, Adams knows that these kids either are potential recruits to keep the bloody conflict in Northern Ireland going for another generation or have a chance to live beyond sectarian hatred in peace. But after observing Adams closely in Belfast, Dublin, and London, where he is by turns reviled as an apologist for terrorism and embraced as the great green hope, one begins to grasp the Sisyphean nature of his struggle and to see what a consummate juggler he is.

As president of the Sinn Fein party, the political arm of the Irish Republican Army, Adams has assumed a terrible responsibility: weaning the insular, ruthless, and unstoppable I.R.A. away from more than two decades of violence. Without alienating the Republican “hard men,” who see anything less than a united Ireland without Britain as unacceptable defeat, he must somehow help engineer a satisfactory political settlement with the British government and the recalcitrant majority population of Protestant Unionists in Northern Ireland. With the help of “Irish America’ and direct White House intervention, Adams was instrumental in delivering the I.R.A. cease-fire which lasted from August 1994 to February 1996.

Then the cease-fire tragically broke down. After 17 months of what the I.R.A. considered British intransigence, it resumed bombing, and since February three bombs on British targets have killed three people. Within 19 days of the first of these bombings, the British suddenly called for talks, once again sending the message, Sinn Fein said, that they respond only to violence. Meanwhile the British said Sinn Fein would be excluded until the I.R.A. restored the cease-fire. Then last summer British security forces fired more than 5,000 plastic bullets at Catholics during and after a protest against a Unionist march through a Catholic neighborhood in Drumcree. In the aftermath, 2 died and 240 were wounded. The attack sent shock waves through Nationalist Ireland (read Catholics and/or those who want a united country), reviving fears that Catholics living in Northern Ireland could never trust local authorities to protect them. Meanwhile, the talks are sputtering on, chaired in Belfast by former U.S. senator George Mitchell. But without Gerry Adams at the table, or John Major and the various parties agreeing as to how another I.R.A. cease-fire can be obtained, the chance of their success is slim. Even if a new cease-fire were to come about, there is no guarantee that the Unionists would not walk out. Anyone who has seen the movie Michael Collins, about the intelligence chief of the I.R.A. who negotiated the partition of the six counties of Northern Ireland in 1921, only to be assassinated at age 31, realizes how seductive and elusive the dream of a united Ireland can be.

Moreover, in the House of Commons today, the conservative votes of its 12 unyielding Unionist members-virtual descendants of Protestant King William of Orange, victorious over Catholic King James II in 1690-hold the balance of power for John Major’s precarious one-vote majority and also keep it “hanging by an orange thread.” To complicate matters further, the Unionists are joined in their veto power by Tory backbenchers who believe that any give regarding Northern Ireland may lead to a domino effect that will make the natives in Scotland and Wales equally restless. Both these groups view Gerry Adams, if not as the Devil’s adjutant, at least as his messenger boy. Unionist leaders such as the Reverend Ian Paisley, who sees the Pope as the Antichrist, have no interest in sharing power or moving Northern Ireland away from British rule. “John Major has said on a number of occasions that he will not be the British prime minister who will preside over the breakup of the United Kingdom,” says Adams. “There’s a certain mind in the British Tory party who think they still have an empire, and we’re it.”

Not only that: to the south many prominent Nationalists in the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland-whose economy is currently enjoying record growth as part of the European Union–are less than enamored of receiving their bloodied northern brethren, particularly Gerry Adams, into the fold. “I think he’s a pariah among that class,” says Sally Mimnagh, a Dublin bookseller who stocks Adams’s books. “But there is a huge amount of respect for Adams among working people.”

Only three years ago Adams, who is 48, was considered so subversive that he was not even allowed to be seen on Irish television; in Britain until 1994, Adams could be seen on TV, but his voice was dubbed by actors. Subject to an “exclusion order,” he was not allowed to travel to England even though he is a citizen of the United Kingdom and was an elected member of Parliament for 10 years. In 1994, under former prime minister Albert Reynolds, the Irish changed their rules on broadcasting, and seven months after Adams had received a tumultuous reception in New York in February 1994, the British rescinded their restrictions. Still, the first time Adams appeared on one of Ireland’s most popular TV shows, The Late Late Show with Gay Byrne, two years ago, Byrne was told that his show would be canceled if he shook Adams’s hand. Last September, however, the line in Dublin waiting for Adams to autograph his autobiography, the No. 1 best-seller Before the Dawn, stretched for blocks, and he signed copies for seven hours.

Perhaps Adams’s star power, fueled by his dangerous reputation, is the most subversive thing about him. On Black Mountain, however, Adams, who is six feel one with penetrating dark eyes and undeniable charisma, seems less the controversial pol-cum-celebrity author and more the earnest instructor who has written five books of nonfiction and two volumes of sentimental stories about life here. He points out various sights of Belfast to me: the shipyards where the Titanic was built, the rusted-out factories where few Catholics could ever obtain even the most menial of jobs. “Catholics lived under the penal code.” West Belfast grew up where it did, Adams says, “because Catholics were forbidden to live within the city walls.”

High up on the hill opposite us is Stormont Castle, the site of Protestant-dominated Northern Irish government from 1922 until 1972, when the conflict between Catholics and Protestants raged so far out of control that the British came in and took over governing their “statelet” themselves. Their major achievement, according to a previous government official, was to maintain “an acceptable level of violence.” “Once the British took responsibility directly, it was the worst of all possible situations, because they were military people,” Adams says. “And military people come up with military solutions.”

A local man strolls over and hands Adams a pair of binoculars to give him a closer view of the new British barracks being constructed nearby. Currently there are 17,000 British troops stationed in Northern Ireland. “Look, Gerry, it’s all ground-level, and they’re planting grass. That means the bunkers are underneath.” I ask the man, “Have you been in prison?” “Aye,” he says, glancing at Adams, who smiles ever so slightly. It is probably a superfluous question around here. “These people don’t worry about a lot of things you and I worry about,” Niall O’Dowd, publisher of the Irish Voice and Irish America Magazine, has told me. “Life is lived at a much different pitch. Day-to-day decisions are all about putting your life in danger or not.”

Below us, snaking through dilapidated West Belfast, are the oxymoronic “peace lines,” walls built to keep Catholic Republicans and Protestant Loyalists from tearing at each other’s throats. Along them are the guard towers of the British special forces, which look like sets from World War II movies. Only they’re real, and “the Troubles”-which began in 1969, when Catholics, who had been gerrymandered out of fair representation and had organized civil-rights marches based on those led by Martin Luther King Jr., were attacked by Protestant gangs-have now gone on for 27 years. More than 3,000 Catholics and Protestants have been killed, and many thousands more wounded.

“What we’ve had here for a long time is an apartheid statehood,” says Adams. “You have Ireland, a small island, partitioned. You have the British maintaining control over this part of the island. And in order to maintain that control, they give a section of our people-the Unionists-a position of privilege, or perhaps a perception of privilege. Because at the working-class level, they got whatever jobs there were, but in terms of living conditions they weren’t much better off than their Catholic neighbors.”

Adams has spent a total of four and a half years in jail, has been beaten senseless and interrogated for days at a time, and in 1984 was wounded with four bullets by a would-be assassin. For more than 20 years he has not slept in the same place in Belfast two nights in a row. For appointments and interviews, you do not go to him — you are taken to him. His wife, Colette, and his 23-year-old son, Gearoid, a Gaelic hurler, have had a grenade thrown into their house. He shows me the patch of grass on a narrow street in Ballymurphy, at the north end of the Catholic Falls Road, where his boyhood home, part of a housing project, once stood.

In a little house here at 11 Divismore Park, Adams lived with his parents and nine brothers and sisters until he came to be seen by the British military and the local police — the Royal Ulster Constabulary (R.U.C.) — as a native menace. “We had a community uprising, a very popular uprising, and the British army were obviously targeting those whom they wanted to take out of circulation, and I was one of those,” Adams says. Before that, after dropping out of St. Mary’s School, he had worked as a bartender and led demonstrations for better housing. “Almost the best part of the struggle was ’68 to ’72ish, because then the armed struggle was very much the lesser part of it. More people were involved.”

In August 1971, when he was 22, the British began rounding up suspected I.R.A. members to be “interned,” meaning held indefinitely without charge, trial, or due process. (Despite the fact that the Unionists had begun the killing, only a handful of Unionists were interned. The British were censured by both the European Court of Human Rights and Amnesty International for their brutal treatment of Republican prisoners.) Adams’s father, “Big Gerry,” had been jailed for I.R.A. activities from the time he was 16 until he was 21, though Adams says he was not particularly aware of growing up with “a Republican acoustic.” Nevertheless, the Adams family, associated with Republican activism on both sides for generations, was singled out. Big Gerry was arrested the night before internment was instituted on August 9, 1971. That morning Gerry’s mother fled with the younger children. Thus began 25 years of one or another of Gerry Adams’s relatives — or himself — being imprisoned by the British.

By Adams’s account, special-forces members threw canisters of tear gas in the windows of his family’s house, repeatedly rammed the facade with an armored vehicle, and ended up smashing the sinks and defecating on the furniture. “My mother never came back,” he says as we lean on the wire fence enclosing the lot and he points out the space where his father, a frequently unemployed construction laborer, built a shed in the backyard. Gesturing around the neighborhood, he says, “I can only describe this as a killing zone.”

Adams shows me the cul-de-sac not far away where one day, while lying on the floor of one of the houses to hide from British soldiers, he proposed to his wife, Colette McArdle, another neighborhood activist. “If we get out of this, I’m going to marry you,” he whispered to her.

The hunger strikes declared by Republican prisoners in Maze Prison in 1980 and 1981 provided Adams’s most wrenching and dramatic involvement with life and death. Ten men ranging from 23 to 30 died after Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher ordered British authorities not to yield to their demands to be treated as political prisoners instead of as common criminals. Some Mother’s Son, the current film starring Helen Mirren and Fionnula Flanagan, tells the story of the hunger-strikers and their leader, Bobby Sands, who was elected to Parliament not long before he died of starvation.

Adams, who got to know Sands in jail, acted as go-between for the prisoners, their families, and the British authorities. Ironically, the idea of putting Bobby Sands up as a candidate ultimately galvanized Sinn Fein into electoral politics-its unofficial motto became “The armalite [rifle] and the ballot box” — and began a process that eventually got Adams himself elected to Parliament twice, though he would not take his seal. “I won’t take an oath of allegiance to an English queen.” Previously the I.R.A. and Sinn Fein had followed an abstentionist policy, but the worldwide tidal wave of sympathy for Sands in the wake of his death, Adams writes in his autobiography, “had a greater international impact than any other event in Ireland in my lifetime.”

Despite such a catalyst for transformation, the Unionists and Nationalists continued their strife. In 1984, Adams was shot in the neck, shoulders, and chest while riding in a car with four others after leaving the Belfast courthouse. Within minutes of the incident, British security officers in an unmarked car which had been following Adams apprehended two Loyalist paramilitary gunmen, who were sentenced to 18 years in prison for the crime. According to Big Boys’ Rules, by Mark Urban, former defense correspondent for The Independent in London, army intelligence had been tipped off about the murder plot but had waited until Adams was shot before intervening. The British army insisted that its presence in the area was a “complete coincidence.” Sinn Fein spokesman Richard McAuley says his people took Adams from the hospital as soon as they could. “We had to keep an eye on the R.U.C. not to let someone come in to finish him off.”

“We are born in separate hospitals, we attend separate schools, we register at separate unemployment exchanges, and, to add insult to injury, we are buried in separate graveyards,” the Protestant ex-paramilitary leader David Ervine, head of the small Progressive Unionist Party, tells me in his hole-in-the-wall office on Shankill Road, the main Loyalist thoroughfare in Belfast. Like many of his counterparts in Sinn Fein, he has spent several years in jail — for possession of explosives and arms — and he recently received his 10th death threat. “I really don’t do anything anymore that could be familiar. I can’t go watch my son play football or go shopping with my wife.” He has never met Gerry Adams, though they passed each other once in a corridor in Washington.

“We fight for two grand dreams,” Ervine explains. “I’m a British Nationalist, and he’s an Irish Nationalist. The backdrop of all those dreams is that everything else is lost. A pathetic education system, bad infrastructure within Loyalist and Republican working-class areas, lack of employment, destruction of family life. They are all on the back burner because of the adherence to the grand ideals of dreams.” Yet, he says, “the one thing that won’t allow us to have anything in common is the tendency of both sides to have a sense of domination.”

I asked Adams if he thought that living together meant the conquest of one side by the other. “I think we can come to an accommodation,” he said. “I’m not interested in the conquest of the Unionists. I don’t think that what I would see as having happened to us should be repeated upon the Unionists. At every level it is wrong.”

During my time in Belfast, the news broke that the British had foiled a potentially huge I.R.A. plot in London, discovering 10 tons of explosives and killing a suspect, 27·year-old Diarmuid O’Neill, in a shoot-out, while arresting five others. (It later turned out that O’Neill, who was shot 6 to 10 times – reports varied — was unarmed.) That morning, September 23, Adams, at a neighborhood meeting to decry the inadequacies of local housing, told the media that he “regretted” the death. and that circumstances such as these were the result of the “dangerous vacuum” the British had created by not allowing the peace process with Sinn Fein to go forward.

Once the reporters had their sound bites, I was instructed by Big Eamonn, Adams’s brother-in-law and driver, not to ride to our next stop, at the Belfast BBC, in the same car with Adams, but to get into a car driven by another ex-prisoner, Cleeky Clarke. I soon realized that it was for my own protection. Clarke was chatting about the liberation theology Adams used to drill into them in prison when a car carrying three men with walkie-talkies came out of nowhere and pulled up alongside us. The three men in my car suddenly began speaking rapidly in Irish.

“It’s O.K., they’re ours,” Clarke said finally, and the awful tension was defused. Later, after we had entered West Belfast, we saw a member of the R.U.C. get out of a gray jeep and set up a roadblock. Big Eamonn pulled over briefly, but the policeman waved him on. “He already knew who we were, plus we own West Belfast,” Big Eamonn told me after we arrived at Sinn Fein’s cavernous headquarters in an old linen mill. “They wouldn’t stop us to mess about in front of a journalist. At times they would’ve asked Gerry to get out. It’s a childish game they play, a form of harassment. Yeah, we would have been under surveillance since leaving the BBC.”

Why are the British still after Adams, and why have they pursued him so doggedly since the 70s? Why did he spend so long in jail even though he has never been convicted of any crime — except an attempted prison escape — including being a member of the I.R.A.? And why was Adams suddenly yanked out of jail in 1972 to participate in hastily called high-level peace talks with the British, only to be re-arrested and beaten up a short time later?

According to the British, there is only one answer. They believe that Adams was part of the leadership of the I.R.A., and that when he joined it, at 16, the difference between Sinn Fein and the I.R.A. was nonexistent. “You don’t become the president of Sinn Fein for standing in the dark,” says Belfast reporter Eamonn Mallie, who has co-written a book on the Provisional I.R.A. In the book, he states flatly that by the time Adams was 23 he was the Belfast Brigade second-in-command of the Provisional I.R.A. (The younger, more sinister “Provos” split from the southern-based “Official” I.R.A. in 1970.) Other books confirm Adams’s high status in the terrorist organization. Adams has consistently denied this, and his denial absolutely infuriates the British. “He’s extremely clever and extremely devious,” says Conservative M.P. Michael Mates, the former minister responsible for security in 1992-93. “He looks you straight in the face and gives you barefaced lies. Of course, that’s what terrorists do.”

The British, who invest heavily in “psych ops” — psychological warfare, media manipulation, and disinformation — in Northern Ireland, and have been attempting to track Adams’s every move for a quarter of a century, have never offered conclusive proof that he is a terrorist. In our first interview, he categorically denies any association with the I.R.A.

Thus begins a Kabuki scenario that every chronicler of Adams is forced to participate in, knowing that the truth is somewhere deep behind the fan that conceals him. “I’ve never seen myself as an apologist for violence or even for the I.R.A. The I.R.A. have their own spokespersons, and they make their own case,” says Adams. “At all times I have made it clear that I have not been involved with the I.R.A.”

“Ever?”

“Ever. I’ve also made it clear that I won’t distance myself from the I.R.A., both because I think it would be wrong and, second, it would mean my influence in the situation would be diminished.”

In the foreword to his autobiography, Adams explains that he is concealing certain situations in order to protect individuals, but he frequently leaves the reader hanging with regard to what exactly he was doing in those situations. At one point he writes that killing is wrong, but sometimes “there was no choice.” That is part of a fictional episode he switches into to describe the feelings a young man has as he fires on a British soldier. “This is a wee story about the sniper, which I had actually entered anonymously for a writers’ competition years ago,” says Adams glibly. “I could have written the same story about a British officer.”

Adams is not easy to pin down. When I ask why he was taken out of prison to negotiate with British authorities, he answers, “Because the Republicans asked. I think it may have been a convenience for the British. They would have taken whomever out of jail they were asked to.”

“They must have thought you were terribly important, or the Republicans thought you were important.”

“Yeah. Whether they thought I was important or not, they obviously thought I could make a contribution.”

“Why?”

“Well, you’d have to ask them.”

“Why did the Republicans think you could make a contribution? They must have considered you a leader. It was an armed rebellion.”

“It was a multifaceted rebellion, and what you were talking about was bringing people together to talk about peace.”

“Do you deny you were an I.R.A. battalion commander?”

“Yes, I do.”

“You never pulled the trigger or planted a bomb?”

“No.”

“You never checked out the route for a killing?”

“No. My position — and we could talk about it forever — is that I have not been involved with the I.R.A.”

In Phoenix: Policing the Shadows, the story of Ian Phoenix, the head of the Northern Ireland police counter surveillance unit, which was recently published in Britain, the authors, Jack Holland and Susan Phoenix, the detective’s widow, claim that by 1993 sophisticated surveillance equipment used by the police and Britain’s domestic-intelligence branch, M.I.5, “had built up a detailed picture of the republican movement’s structure-financial, political and military. It showed considerable overlap between the leadership of Sinn Fein and the Provisional IRA.” Gerry Adams, onetime “ ‘Northern Command’ Number 2,” according to the book, was one of four people on the I.R.A.’s governing Army Council of seven who also “held high positions in the political party.”

It was only in October 1995, says Holland, that Adams left the Army Council. Michael Mates, the former security minister, told me that Adams left for “tactical reasons.” “It’s rubbish,” Sinn Fein spokesman Richard McAuley scoffed. “Gerry would need 48 hours every day to do all these things people claim he’s done.” I contacted Holland, a native of West Belfast who writes for the Irish Echo in New York, to ask if he had seen hard copies of transcripts of surveilled conversations kept by Ian Phoenix, who died in a helicopter crash in 1994. “I saw concrete evidence that Adams was involved in meetings with high-ranking members of the I.R.A. as late as November 1993.” He added, “I’ve seen names, dates, and places.”

According to Holland, the data have been deliberately suppressed by the British. “Because of Adams’s political value and his influence over the I.R.A., they realized he might be the guy who could deliver a cease-fire, and why jeopardize it by proving he’s in the I.R.A.?” McAuley counters that Holland should produce the physical evidence. Otherwise, Phoenix’s claims should be treated as “pure propaganda.”

Ironically, Adams’s most potent weapon has always been words. In his autobiography he recounts that when he was stopped by British soldiers, who could have arrested him, he always managed to talk his way out of it. Adams’s main technique to keep from breaking under interrogation was to lie away his very existence, to refuse “to admit that I was Gerry Adams,” In Long Kesh Prison, where Adams debated and instructed endlessly, he was considered “ultra-leftist.” (One of the people he thanked in his prison book, Cage Eleven, was Ho Chi Minh.)

For most Unionists, Adams’s gift with language makes him deeply suspect. “The Protestant view of the Catholic Irish stereotype is that he is a mendacious fellow handy with words, and if you get into an argument with him, you can only lose with words,” a former official of the Northern Ireland government told me. “Unionists find it easier to respond to force.”

Adams acknowledged that his power derives from his “ability to bring Republicans to the negotiating table and keep them there.” To be effective, however, he must bring them all in. “What would be the point if he brought half into the cease-fire and half continued to wage war?” asks Eamonn Mallie. “He can’t condemn. This is like asking Nelson Mandela to condemn the African National Congress during the struggle for independence. The only power revolutionary leaders have is to stay with the foot soldiers.”

“Adams has privately said that they’d kill him if he distanced himself publicly from them — the hard men,” a former high-ranking British official told me. The British, of course, have negotiated secretly with Adams for years, even though John Major got up on the floor of Parliament and said it would “turn my stomach” to talk to Gerry Adams.

“If the politics of condemnation could have resolved this problem, it would have been resolved 30 years ago,” says Adams. “I would disempower myself if I slipped into that type of nonsense where moral denunciation becomes a code for political advancement.”

I tell him that when innocent civilians are blown up and all he says is that he “regrets the mistake,” people don’t feel his language is strong enough. “I have never attempted to condone or justify or explain any action in which civilians have been either injured or killed,” he responds. “Second, even in terms of this interview, I no longer see it as my role to answer questions like this. I wouldn’t answer questions like this with local journalists.” He is clearly annoyed. “We have moved beyond all that. Sinn Fein has a credibility because people know we’re taking risks for peace.”

By the next day Adams, who is extremely courteous, is more relaxed. I bring up an item in a British paper. Adams used to write a column for a Republican newspaper under the pseudonym Brownie, and the London Sunday Times has printed an excerpt: “Rightly or wrongly I am an IRA volunteer. The course I take involves the use of physical force. . . . . Maybe I won’t fight again . . . . but I will move aside for the fighter.”

“Are those your words?” I ask him.

“We’ve been through a sort of trying moment — back to our discussions yesterday about all these questions,” Adams replies. “All I can tell you is that if I had written that, it would be worth at least 10 years in jail. So I wouldn’t like you to write anything that’s going to put me in jail.”

“A nondenial denial?”

“That’s a judgment you have to make, you know.”

The hatred of Gerry Adams in England is palpable. Londoners told me that allowing Adams to come to America was tantamount to having the English invite the Oklahoma City bomber for a visit. He symbolizes I.R.A. atrocity –the killing of 121 people, including Lord Mountbatten, in England since 1969; the car bomb outside Harrods in 1983, which killed 5; the attempted assassination of Margaret Thatcher in Brighton in 1984, killing 5; the explosion in London’s financial district in 1992, which caused more than $1 billion in damages and killed 3.

“We English are very badly equipped to deal with the Irish, because we’re not poets. The Irish are all poets,” Sir Edward du Cann, former chairman of the Conservative Party, told me. “The English find them impossible to understand — why they fight each other, why they’re so dogmatic, why they speak with such a total lack of logic, wholly ignoring the point of view of the Unionists. There’s no reality in Ireland. It’s a land of fairies, of pixies and leprechauns.”

“I’m really cheesed off I have to go do this book tour in London,” Gerry Adams said. Without telling him, his London publisher had obtained a room in Parliament for Adams to launch his autobiography. As a former M.P. he was entitled, but with the headlines screaming about I. R.A. terrorism and Diarmuid O’Neill’s being killed, Adams was reluctant to go. For two days the London papers raged about his arrival. Labour leader Tony Blair threatened to oust M.P.’s Jeremy Corbyn and Tony Benn, who had invited Adams, from the party.

Adams decided not to force the issue. Instead, he held a press conference at the London Irish Centre in nearby Camden, entering like a rock star, with an entourage wearing green ribbons for the I. R.A. “prisoners of war.” Adams is ultra cool under fire; questions about his book profits’ being blood money didn’t seem to faze him. Even while answering questions, he often doesn’t answer them.

On BBC radio, interviewers opened up on Adams with both barrels. For example: “You’re asking us to believe they, your friends and colleagues, were going out there, joining the I.R.A., killing people, but you — even though you felt as strongly as they about the injustice of it all, in your terms — decided not to join them. Really?”

On a call-in show, Adams’s first opportunity to talk with ordinary Britons, one man snapped, “When you talk of Hitler, ldi Amin, and Saddam Hussein, then mention in the same breath Gerry Adams, for he is an evil man and a disgusting coward.” Unionist M.P. Ken Maginnis followed Adams on the show and said that Adams “personifies all that is evil in the terrorist campaign that we’ve had for over 25 years.”

Outwardly, there was little to indicate that any of this was getting to Adams, but it was. In a van leaving the morning press conference, Adams said to his aides, “Do ye not know that I also need time not to be talking to anyone for a while, just to be by myself, alone?” Later, as he was being crammed into a crowded elevator to go before another barrage, he said plaintively to his press aide, Richard McAuley, “Richard. I need I hug.”

On the night after St. Patrick’s Day 1995, I was present in the State Dining Room at the White House to witness John Hume, the leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, the Martin Luther King Jr. of Irish Nationalists, sing a duet of the Derry song “The Town I Love So Well” with his political arch-rival and peace partner, Gerry Adams, Ireland’s Black Panther. Although no one knew it then, that spontaneous moment between the two pivotal figures of contemporary Irish nationalism was the highlight of the Northern Ireland peace process.

It was the result of a dialogue begun by the two nearly a decade earlier. And it was fueled by the trust between former Irish prime minister Albert Reynolds and John Major, which allowed them to issue the Downing Street Declaration of December 1993, stating that Britain had no selfish strategic or economic interest in Ireland, and that Irish unity would not be imposed without the consent of the governed. Major also said that Britain would begin all-party peace talks within three months of a cessation of violence.

Hume and Adams’s attempt at harmony was brought about by a remarkable Redemptorist priest, Father Alec Reid, of West Belfast’s Clonurd Monastery, who had grown close to Adams, a practicing Catholic, and understood his increasing desire to break out of the political isolationism in which he found himself. “He is the real catalyst, the facilitator,” Adams told me. “I would now consider him to be a dear friend . . . . I think he has redeemed the Catholic Church in Ireland on this whole issue of conflict resolution. There isn’t an Archbishop Tutu here.”

Reid has been described as a “Christian electrician” for trying to wire together Republicans and the Irish government. The image of him weeping over the body of a British soldier set upon by a Catholic mob and executed by the I.R.A. in 1988 has become an icon of “the Troubles.” That same year, according to Eamoun Mallie and David McKittrick’s absorbing book, The Fight for Peace: The Secret Story Behind The Irish Peace Process, after securing permission from the Catholic primate of all Ireland, Cardinal Tomas O Fiaich, Reid secretly arranged for delegations from Hume and from Adams to meet at the monastery. “[We asked] them to state their reasons [for violence].” Hume told me. “Their reasons were that the British were in Ireland defending their own interests by force-economic and strategic interests — and preventing the Irish people from recognizing their right to self-determination. My response to that was that was true in the past but not today. . . . . We are all together in the new Europe. Secondly, the Irish people have the right of self-determination, but the Irish people are divided on whether the right is to be exercised.”

Hume, who is 59 and has represented Foyle, which includes Londonderry, in Parliament since 1983, has put himself under great strain and withering criticism for consorting with Adams, especially when they issued a series of joint statements, the Hume-Adams documents, in 1993. “It was a very difficult period,” Hume told me. “When it became public, the attacks were relentless and regular.” He persevered, he said, “because if as a political leader I could save a single life by dialogue, then it was my duty to do so.”

In Hume’s book, A New Ireland, he says that 55 percent of the people “who died in the Troubles in the North were innocent civilians — people killed ‘by mistake’ or in tit-for-tat revenge killings by Loyalist paramilitaries.” Also, “of 279 Nationalist paramilitaries who lost their lives, 117 were killed by the security forces, 20 by Loyalists and 142 by themselves, either in ‘accidents’ [usually with explosives] or [punishment] ‘executions.’” These numbers alone had to indicate to Sinn Fein that it was clinging to a failing strategy.

“I do give John Hume great credit for the part he played in the process,” says Adams. “He knows that you cannot marginalize people.”

But the peace process might never have moved forward at all if it had not been for a series of diplomatic steps undertaken by a group of Irish Americans who were able to win over President Clinton, who then went against the State Department and, for a time, severely strained our relations with Britain. All because of Gerry Adams.

In the White House that night were gathered the cast of characters who had stuck their necks out for Adams: National Security Adviser Tony Lake and his deputy Nancy Soderberg; Senators Ted Kennedy and Chris Dodd; billionaire Charles “Chuck” Feeney, Robert Miller’s estranged partner in the duty-free-shopping empire; Bill Flynn, C.E.O. of Mutual of America Life Insurance; publisher Niall O’Dowd; former Connecticut congressman Bruce Morrison, a Clinton classmate at Yale and a Lutheran; and ambassador to Ireland Jean Kennedy Smith.

It was the sixth month of a total cessation of violence by the I.R.A. and their counterparts, the Loyalist paramilitaries, who were represented that night by Gary McMichael of the Ulster Democratic Party. The mood was hopeful. Albert Reynolds had put Northern Ireland at the top of his agenda and had, in effect, led Adams in from the cold. Hume, who was a favorite of the Kennedys’ and had wide contacts in the States, had gone to Reynolds shortly after the latter’s election in 1992. “He believed that there was a window of opportunity to be exploited, and he couldn’t take it any farther if the two governments weren’t prepared to take up the initia¬tive and run with it,” Reynolds told me. “Humc brought me in and said. ‘You bring in Major,’ and I also brought in Clinton. J told them that it was my view that [Gerry Adams’s] morals had changed and he was traveling a very different road”

In fact, Adams was working both sides of the street. On one side were the Irish government, the British government, and the secret dialogues he was carrying on to attempt a breakthrough in the stalemate. On the other were the Republicans, whose reliance on violence, Sinn Fein spokesman Richard McAuley told me, was so strong that it “was like a comfort blanket, something they’re used to that leads to people getting killed. . . . You’ve got to move away to another situation they feel equally comfortable with, and Gerry did that with the Republicans. . . . Gerry took us through a painful barrier of having to assess who we are, what we are, where we want to go, and how are we going to go there.”

In 1986, Adams led the Sinn Fein convention to abandon abstentionism and enter into electoral politics on the national level. Encouraged by Father Reid, he also began to meet in secret talks with a small group of Protestants at the Clonard Monastery. “We asked him, ‘Are you willing to do more than just talk about making peace and pursue the peace process?’” says Presbyterian minister Ken Newell. “In private he has been very critical of the armed struggle. I know from things he’s said in private that he regrets every British soldier brought back in a coffin.”

For his leadership Adams was now being rewarded at the White House party. It is not lost on the president, of course, that in the last census 38 million Americans described themselves as Irish-American, or that in the last Forbes-magazine list of the 400 wealthiest Americans one out of four had an Irish name. The day before, Clinton had met Adams for the first time at the traditional St. Patrick’s Day Speakers Lunch on Capitol Hill, begun by the late Tip O’Neill and continued by Newt Gingrich. Irish Times correspondent Conor O’Clery reports in his excellent and engrossing upcoming book, Daring Diplomacy: Clinton’s Secret Search for Peace in Ireland, that Adams was still considered so radioactive that their handshake was not allowed to be photographed. For added protection, as Clinton shook Adams’s hand, his other arm was draped around the apostle of nonviolence, John Hume. Now a beaming Clinton toasted, “Those who take a risk for peace are welcome in this house.”

But across town in the British Embassy and at No. 10 Downing Street in London, the British were so outraged at Adams’s having been allowed into this country that they became in no small part responsible for turning him from an outcast into a celebrity. As Adams says, “If the British had never opposed me getting a visa to the States, who ever would have noticed me going to the States?”

The visa was the centerpiece of a package deal. Hume told Reynolds that the hard men needed to be convinced by concrete actions on a governmental level that laying down their arms would result in fundamental changes. Before they gave up violence, they wanted proof. “That was basically demonstrated to Sinn Fein and the whole Republican movement by lifting the ban on interviews, [amending] the Broadcasting Act,” says Albert Reynolds. “That was a big step forward. The next big battle was the visa.”

Now it was the Americans’ turn to take center stage. At the hotly contested New York Democratic primary in 1992, a group of “concerned Irish Americans” had extracted from candidate Clinton the promise that, if elected, he would grant a visitor’s visa to Adams. After Clinton’s election, a coalition of politically active Irish in America believed that they now had sufficient clout to build their version of the Jewish lobby which so effectively fights for the interests of Israel. (It appears to be happening. New York State just passed a law mandating that Ireland’s potato famine be taught in public schools alongside slavery, genocide, and the Holocaust.) “I was shocked to find out how many C.E.O.’s are of Irish heritage,” says Bill Flynn, “in both traditions, Catholic and Presbyterian.” It also helped that Clinton had never forgotten how Major’s Conservative Party sent two operatives to work for George Bush in the 1992 election.

The State Department and the Justice Department had seven times in the past denied Gerry Adams’s request to visit the U.S., basically to raise money for the Nationalist cause. In 1988, former deputy secretary of state John Whitehead said in an affidavit that he had considered Adams a terrorist since 1983. Then, shortly after Clinton’s election, Niall O’Dowd went to Dublin to try to make contact with Sinn Fein and see if the I.R.A. would call a temporary cease-fire so that he could bring a delegation of Americans over to talk. On his next trip he met with Gerry Adams. “My main objective was to get in high enough to the I.R.A. so I could put a serious proposal in about how to reach out to America,” says O’Dowd. “The State Department and the British never even saw us coming.”

O’Dowd preached the “box theory” to a Sinn Fein representative: “They had to come forward. All the players were locked into this little box. Each move has a countermove, and nothing ever gets done. So you pitch in an outside force –the U.S. — whose dynamic changes it forever. That’s what happened.” Finally, in September 1993, O’Dowd, Flynn, Feeney, and Morrison went to Ireland for talks with a variety of people, including Albert Reynolds, who was trying to put the Downing Street Declaration together, and the I.R.A. granted them an unprecedented seven-day cease-fire. The Americans now looked at Adams with fresh eyes. Feeney told me, “Right from the first time we met, I felt a certain charisma in this man.” Flynn adds, “He’s a man of honor. He means every word he says.”

The Americans kept the National Security Council advisers at the White House informed of their every move. All through 1993 and 1994, Reynolds was being moved past heads of far larger countries and “getting lots of time with the president,” Bruce Morrison told me. “To the untrained eye, nothing much was happening. But there was a conscious attempt to raise his stature.”

O’Dowd’s contact inside the White House was N.S.C staff director Nancy Soderberg, but she did not talk to him directly; she wasn’t even sympathetic to him, because he had written articles critical of her former boss Ted Kennedy and his stance on Northern Ireland. Kennedy was totally opposed to those who used violence. Moreover, Soderberg needed deniability if anything went wrong. Their device was to talk through Trina Vargo, who works on foreign-policy issues for Senator Kennedy. Meanwhile, John Hume was also talking to Soderberg and discussing Adams with the new American ambassador to Ireland, Jean Kennedy Smith, as was Albert Reynolds. Reynolds told me, “I also called John Major and told him straight up what I was doing. He told me he would be opposed.” Conor O’Clery writes that Jean Kennedy Smith’s first reaction to changing U.S. policy was also negative. She reportedly said, “These are the kind of people who killed my brothers.” By December 1993, however, when Ted Kennedy went to Ireland for a visit, she was convinced, and at a private dinner at Reynolds’s apartment she helped convince the senator.

At Tip O’Neill’s funeral in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in January 1994, Ted Kennedy asked John Hume if he wanted Adams to have a visa. Hume said yes. That did it. The Irish then had Kennedy’s enormously influential support. “John has been the rudder for us on Irish-American issues,” Senator Chris Dodd, who also became an Adams supporter, explained to me. All of this was kept secret. “Teddy was the rainmaker,” says Niall O’Dowd. “He gave Clinton the space to act.” Clinton was indebted to Kennedy. “The 180-degree turn really starts with the Kennedys — a powerful senator having been extremely helpful to a first-term president,” a White House staffer told me.

Meanwhile, the private-sector wheeler-dealers were getting impatient with the pace of diplomacy. To force the issue, Bill Flynn came up with the idea of inviting Adams to a one-day peace conference in New York set for February 1, 1994, and sponsored by Flynn’s privately backed group, the National Committee on American Foreign Policy. Morrison says, “It was, give the White House a proposal they couldn’t say no to.”

The visa issue now started to become public. Jean Kennedy Smith went against the wishes of two of her top deputies and recommended that Adams be granted a visa. The way she handled their opposition later caused her to be reprimanded by Secretary of State Warren Christopher. Ted Kennedy got Senators Daniel Patrick Moynihan, John Kerry, and Dodd to sign a letter to the president in Adams’s behalf. Then The New York Times weighed in with a favorable editorial, and influential members of Irish America started a lobbying effort.

The State Department and the British Embassy were appalled. They usually saw eye to eye on Northern Ireland. “When Adams first applied for a visa, we said to the White House he shouldn’t be given a visa until the I.R.A. declared a cease-fire or at least he had called on them to,” said Sir Robin Renwick, who was the British ambassador to Washington at the time. The Justice Department was also opposed, as were the American ambassador in Britain and the Speaker of the House, Tom Foley, a major Anglophile. John Major’s foreign secretary, Douglas Hurd, visited the White House to voice strong disapproval.

Finally, in the latter part of January 1994, the White House tried to get Adams to renounce violence unilaterally by answering some questions posed to him by a U.S. consul. But he couldn’t do it to the White House’s or the State Department’s satisfaction. In the end, after more semantic jockeying, and with only a few hours to spare before his flight was to take off for Kennedy airport, Adams got the visa anyway. It was the president’s decision, and a total gamble.

“The White House was hooked in once it gave the visa to Adams,” Conor O’Clery told me. “It is the first time the U.S. ever went against Britain,” President Clinton personally had to approve the waiver on Adams’s ban. In fact, each of the seven times Adams has come to the U.S. since 1994, Clinton personally has had to approve a waiver allowing him entry, since he is officially still an excluded terrorist. The favor is not lost on Adams. “Any conflict-resolution process in the absence of the two sides all of a sudden having a Damascus Road conversion requires an international dimension,” Adams told me. “President Clinton has radicalized entirely the prospect for peace.”

The British reaction at home and abroad was so strong that it guaranteed saturation coverage. When Adams arrived at Kennedy airport, “it was an absolute mob scene,” says Republican congressman Peter King of New York, a longtime friend of Adams’s. Adams registered as Shlomo Brezhnev at the Waldorf and began a whirl of appearances, starting as a guest on Larry King Live. “It was just a huge helter-skelter,” says Adams. “People here think I’ve seen the States. I haven’t. I’ve seen escalators, elevators, TV studios.”

The British were icy in their revulsion. On CNN, Robin Renwick said, “When I listen to Gerry Adams, I think, as we all do, it’s reminiscent of Dr. Goebbels. It’s an extraordinary propaganda line. The line is ‘I want peace, but only after we’ve won.’” The British press went after Clinton, calling him “guilty of shamefaced deceit.”

In March, a series of dud mortars were shot from an I.R.A. car onto a runway at Heathrow Airport, causing Senator Moynihan to send Ted Kennedy a one-line letter: “Have we been had?” Months later, when Moynihan saw how Ben Gilman, the chairman of the House International Relations Committee, had attached himself to Adams, he wondered aloud, “What next, Ben? A fund-raiser for Hamas?” Meanwhile, Bill Flynn had gone to Belfast at Adams’s invitation. Adams had once said, “The I.R.A. will only be beaten when the wee women [of West Belfast] throw the guns out onto the street.” Now he needed a little U.S.-style salesmanship. “We went over to his people, to convince them, to see them in groups of 15 to 100. We drove in armored cars. I never knew with whom 1 was dealing,” says Flynn. “Gerry Adams was always with me. I would give the message why in this day and age terrorism is counterproductive.” Flynn also opened up extensive contacts with the Loyalist paramilitaries and paid for them to travel to the United States; they too were eventually welcomed at the White House. “We want to sell them on the spirit of America. Northern Irish people don’t seem to have inalienable rights.”

Seven months after getting his visa, Adams was able to arrange what so many had been counting on him for: the cease-fire. But before it could be announced, Adams had one more amazing request: a visa for Joe Cahill, a longtime I.R.A. man who had been caught on a boat in 1973 with five tons of weapons from Libya. Cahill had to go to New York to explain the cease-fire to the hard-core supporters of the I.R.A., some of whom allegedly bankrolled the terrorists. Forget it, Nancy Soderberg said. But the “Irish Mafia” came out in full force, badgering the White House. “Jean Kennedy Smith was wonderful,” says Niall O’Dowd. The president gave in one more time, although, O’Clery reports, he seemed taken aback by Cahill’s resume. The cease-fire was actually announced shortly before Congressman King accompanied Cahill to the upstairs of a bar on Second Avenue in Manhattan, where, he told me, a group of “lawyers and contractors and businessmen” were waiting. On August 31, 1994, a total I.R.A. cessation of the armed struggle was a done deal.

Veterans of the struggle were ecstatic. “I don’t think anyone underestimates the difficulty of transforming that tradition into a peaceful, political approach, given the number of people that they killed and the number of their own members who died,” says John Hume. “That makes it emotionally very difficult for them.” Six weeks later the Loyalist paramilitaries also announced a cease-fire.

The euphoria was short-lived. “It was like, O.K., you made a giant step,” says writer David McKittrick of the British attitude toward the cease-fire. “Now take another one.” The British gave the Republicans almost no credit for what they had done. Instead, they immediately started imposing conditions. First, they repeated their demand that the word “permanent” be attached to the word “cease-fire.” Then, three months later, Albert Reynolds’s government fell, and Adams lost not only a skilled protagonist who worked well with John Major but also someone willing to take risks. The current prime minister, John Bruton. has compared the I.R.A. to Nazis and has not shown dynamic leadership regarding the peace process.

The British were further incensed when Adams was granted another visa to the States to fund-raise for Sinn Fein. They believed the money would go directly into buying weapons for the I.R.A But the Kennedys started lobbying again, and Chris Dodd asked Bill Clinton on the 17th green during a golf game whether he was going to give Adams another visa or not. It turned out that he would, John Major was so furious with the president for not having consulted with him on the fund-raising decision and for having hosted Adams at the White House that for five days he refused to take calls from him.

With justification, the British, as well as the State and Justice Departments, felt that the president was granting Gerry Adams’s every wish without asking for anything in return. Meanwhile, Adams was continuing to wow Washington. “He’s very disarming,” says former director of White House communications Mark Gearan, who is now Peace Corps director. “What I did not know was how effective he would be as a public personality. You have to put a face on policy. He’s been helpful for Americans to better understand “the Troubles.’” With the cease-fire in place, officials such as Senator Dodd were able to meet Adams in person and judge him for themselves. Dodd has a house in Ireland, which Adams has visited, and Dodd now considers him “a friend. He’s a very bright, very intense person of deep conviction. He’s not a backslapper, a guy in a bib singing ‘Roddy McCorley.’”

Peter King took Adams to the Senate Dining Room and to various Washington offices, where he got a warm greeting from Alfonse D’Amato and Jesse Helms. At a reception on the Hill, “congressmen were lined up like kids getting their picture taken with Santa Claus,” says King. “Suddenly he was their hero, a media star.” In New York, Bianca Jagger and Donald Trump attended a $200-a-plate lunch for Sinn Fein. At a $1,000-a-plate dinner at the Plaza, 400 showed up.

Women throw themselves at Gerry Adams, I was told. “I’ve never noticed.” Adams deadpans. “Now I know you lie in interviews,” I say. “I enjoy the company of women,” Adams answers. “The sex act, if you’re very lucky, lasts 15 minutes. Why even jeopardize a relationship which is based on loyalty and love and working through? So it’s just not an issue.

“Colette is a very strong woman, and she has her own identity,” he says. “I often make the joke that in front of every great woman a man has foisted himself. . . . I genuinely couldn’t do what I do if my domestic situation crumbled.”

As Adams’s popularity soared, and he went to parties in Beverly Hills with the likes of Anjelica Huston and Oliver Stone, the British dug their heels in even further The Northern Ireland secretary, Sir Patrick Mayhew, skeptical of the peace process he had little hand in fashioning, sounds eerily like the high British source in Mallie and Mckittrick’s book who suggested that it would take at least two years “getting Sinn Fein up to scratch and all of that” before the British would be ready to talk seriously. “If we play our cards very carefully and don’t let either the republican side or the loyalist side get completely disillusioned, then we’re into a proper negotiated peace. But there’s many a slip ‘twixt lip and cup.”

To Washington’s astonishment, on a lobbying visit in March 1995, Mayhew set forth the most stringent precondition of all: decommissioning, meaning that the I.R.A. would have to give up some of its weapons before it could sit down at the table for peace talks. To the I.R.A., decommissioning means surrender, and Republicans point out that never before in history has an undefeated army had to give up its weapons before it could negotiate.

As the months drifted by without talks being called, Gerry Adams realized that the peace process was crumbling. The major Unionist parties, which would lose power in any settlement, were vetoing Sinn Fein’s presence at the table. Adams began to feel the strain. “You don’t know how many times I wake up in the middle of the night wondering if I am doing the right thing,” Peter King remembers Adams telling him shortly after the Reynolds government collapsed. So far, Adams has not been able to analyze or cajole his way through the maze he has been forced to confront in bringing about a lasting peace.

Certainly everyone’s worst fears were realized last February 9, when the I.R.A. broke the cease-fire and set off a bomb at Canary Wharf in London, killing two. Adams insists he got no advance warning. “It was a trauma to me.” Yet if that is true, what does it say about his power and influence? “If he did know, that’s terrible, but if he didn’t, it’s worse still,” says an Irish-government official. The White House was stunned. Adams was able to warn the National Security Council about the collapse of the cease-fire only a few minutes before the bomb went off. Senator Kennedy was particularly angry, and cut off communication. One While House staffer said, “Adams clearly understands that when the cease-fire ended he would not be welcome here.”

Ironically, within two and a half weeks of the bomb’s exploding, the Irish government got Britain to agree to come to the bargaining table for peace talks headed by George Mitchell. They would discuss an interim government for Northern Ireland, how to structure relations between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland in sharing “cross-border institutions,” and relations between Britain and Ireland. A second I.R.A. bomb went off in Manchester in June, injuring 206, and a third killed a British soldier at the Lisburn army barracks outside Belfast in October — the first to go off in Northern Ireland in two years. Martin McGuiness, one of Adams’s chief deputies, who is known for his close contacts with the militants, says, “Many believe the British don’t come to the table unless you bomb them there.”

Just over a year ago, President Clinton described the reception he got from more than 50,000 wildly cheering Catholics and Protestants in Belfast as “one of the greatest days of my life.” Today, the people of Northern Ireland wait on tenterhooks, wondering whether full-scale violence will erupt once again, or whether there is real hope for another cease-fire. The politics of Gerry Adams “are much more heavily challenged now,” says Presbyterian minister Ken Newell. “But his influence hasn’t waned.” Recently, John Hume, with behind-the-scenes help from the Irish foreign minister, Dick Spring, has been desperately trying to negotiate a new cease-fire-the I.R.A. traditionally calls a short halt to violence at Christmas — under conditions acceptable to both sides. “Gerry and I can go back to the I.R.A., but it will be much harder this time,” says McGuiness, “because the I.R.A. has seen the British government set out over two years to humiliate them.”

The ball is clearly in John Major’s court. “I have no doubt of John Major’s commitment to peace in Ireland,” says Hume. “Had he a clear majority, he would have moved much more quickly, and we would have lasting peace in Ireland by now.” Instead, John Major seems stymied by the Unionists and their parliamentary impact on the arithmetic of Westminster. Some think peace is in the offing. Others believe that nothing will happen until after the upcoming British general elections, when either Major will have better odds or there will be a new Labour government.

“The Protestants should cut a deal,” says Tim Pat Coogan, the Dublin author of The Troubles “The tides of history are overwhelming them.” Catholics now make up 43 percent of the total population of the North. Catholic schoolchildren have a pass rate on university-track exams that is four times higher than that of Protestant children. The Nationalists are moving up, while young, middle-class Unionists are emigrating at a higher rate. If Gerry Adams and John Hume ever cut an electoral deal between their two Nationalist parties, “they would win all the seats,” says Coogan. “We’re ambitious,” Sinn Fein’s Richard McAuley tells me. “We don’t forever see ourselves a small party. We want to be in the leadership of changing society on this island.”

“So,” I ask him, “you want to see Gerry Adams Taoiseach [the Irish word for prime minister] in 20 years?” “Twenty years? He’ll be too old. Five!”

“We’re in the endgame,” Gerry Adams tells me one morning in a crowded van in London. It is a favorite line of his, and given the events he has helped shape in recent Northern Irish history, perhaps he can see the outlines of a future not yet visible to the foreign eye. “It could take one year, six months, or a number of years. Making peace is more difficult than making war.” He adds, “The British say that politics is the art of the possible. I think it has to be that politics is the art of the impossible.”

Originally Published: Vanity Fair January 1997