In his obituaries, last August, it appeared that Mark Birley, the London club owner who died at the age of 77, might go down in history as the man who first wrapped muslin around lemon halves to prevent them from squirting randomly or spilling seeds on his patrons’ perfectly prepared turbot. That horrified his aristocratic friends, for to them Mark had always been so much more—a towering, sardonic, pampered monument to English style, who managed to exemplify the cultivated manners of the playing fields of Eton while introducing edible food in beautiful surroundings and replacing stuffiness with sexiness in Mayfair nightlife. In 1963, when he opened Annabel’s, the first of his string of exclusive, members-only clubs and restaurants—which would eventually include Mark’s Club, Harry’s Bar, the Bath & Racquets, and George—Swinging London had not yet exploded onto the scene, and when it did, it was largely a working-class phenomenon. Birley made the Beatles the first and only exceptions to the strict dress code at Annabel’s, where men were required to wear jacket and tie. If Frank Sinatra or Ari Onassis happened to be in the house, Birley would make sure he was well taken care of, but would never drop by his table to chat. “That would be the headwaiter’s job,” David Metcalfe, the Duke of Windsor’s godson and a founding member of the club, informed me.

Annabel’s had no cabaret, but occasionally performers such as Ray Charles and the Supremes would play one-night stands. When a promoter for Ike and Tina Turner demanded a table for a sold-out performance of theirs at Annabel’s, he was denied. After he stormed out and threatened to cancel the performance, a compromise was reached whereby he would be greeted profusely upon entering and taken to a seat at the bar. In the process, however, he overheard Birley say, “I don’t care if he comes down the fucking chimney,” and so Ike and Tina Turner did not appear that night.

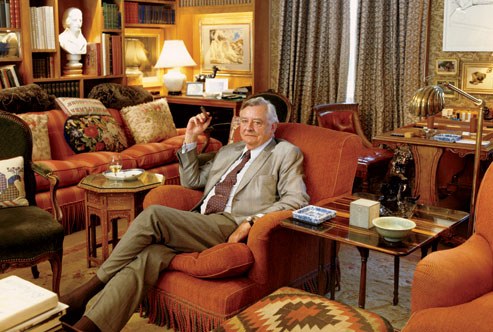

Birley became a familiar sight around Berkeley Square, seated in his chauffeur-driven Mercedes, puffing a Cohiba, with Blitz, his Rhodesian Ridgeback, seated up front. For many in London’s disappearing tribe of old-boy toffs, he represented the quintessential English gentleman, exquisitely turned out, providing impeccable quality and service through a deeply loyal and perfectly trained staff. His eagle eye missed nothing, be it the careless fold of a napkin or the slightly crooked angle at which a painting was hung. He was the upper-class social set’s final arbiter of taste, and cost was never a concern. At Mark’s Club, for example, each silver pepper mill was valued at $800; each mustard pot, $1,000; each blue-striped Murano glass, $100. At Harry’s Bar, the flowers cost $120,000 a year. Birley wandered the world—especially Italy—seeking the best new cocktails and recipes, meeting with world-class chefs, and poaching exceptional waiters. Over the years and all during his marriage, he seduced numerous women, but his real loves were his clubs and his dogs. People could never tell what he was thinking as they bowed, scraped, and competed for his favor, because his stiff upper lip never so much as quivered, even when he endured unimaginable family tragedies.

In 1970, on a visit to the private zoo of John Aspinall, owner of the Clermont Club, the casino above Annabel’s, Birley’s 12-year-old son, Robin, entered a pregnant tigress’s enclosure with his mother and brother and Aspinall and his family. The animal grabbed Robin’s head in her mouth, and the boy’s face was left permanently disfigured. In 1986, Birley’s handsome firstborn, Rupert, 30, ventured out into dangerous waters off the coast of Togo, in West Africa, and was never seen again. Though Rupert was his father’s favorite, any discussion of his demise was strictly forbidden. Similarly, Mark never uttered a word about his wellborn wife, Lady Annabel Vane Tempest-Stewart, for whom his tony club was named, having two children with James “Jimmy” Goldsmith, the late billionaire, before she and Mark were divorced. (She later married Goldsmith and had a third child with him, and he would have two more children with another mistress during their marriage.)

Mark and Annabel remained friends and soulmates until his death, united in their love of dogs as much as in the parenting of Rupert, Robin, and their daughter, India Jane (so named because Mark loved the word India). “He never commented on anything except dogs or something funny—a painting, food, or wine,” India Jane, who is a painter of portraits and dogs, told me of her “formidable” father. “He never showed his deck of cards.” She added, “We all had our work cut out for us with Pup. He could scowl and smile at the same time. For a child it’s a very, very odd feeling. With an adult it’s bliss, because you can figure out the subtlety, but with a child it’s terrifying.”

“Mark really wanted his children to be born at age 21. He liked the children when they were grown,” Lady Annabel explained to me at Ormeley Lodge, her house in southwest London. In fact, she said, he didn’t really want children at all. “Rupert was a mistake—I became pregnant totally by mistake,” she said, adding, “Mark was O.K. with one, but he never really wanted another.” In her 2004 book, Annabel: An Unconventional Life, Lady Annabel writes of how Mark tapped her on the shoulder in the hospital shortly after Robin was born and exclaimed, “Darling, you must wake up. There must have been a mistake. I think you’ve been given the wrong baby—this one is simply hideous.” Lady Annabel told me, “I can’t blame him for not being a brilliant father, because he never really asked to have any of them.”

Given the eccentric family dynamics, it is perhaps less than surprising that a huge fight is now simmering between India Jane, 47, and Robin, 50, over their father’s will, in which he left more than $240 million before taxes. Robin is challenging the will, which gives the bulk of the estate to India Jane’s two-and-a-half-year-old son, Eben, whom she had by a lover, a Canadian named Robert Macdonald, a voice coach and teacher of breathing techniques who was studying to become a psychiatrist. She was married at the time to her second husband, Francis Pike, a banker turned writer and real-estate developer, who currently lives in Berlin. India Jane is now divorced from Pike and no longer with Macdonald. In the will, Robin was left two tax-free bequests, for £1 million ($2,039,400) and £5 million ($10,197,000). Robin’s four-year-old illegitimate daughter, Maud, who lives in charity housing with her mother and who never met her paternal grandfather, was left nothing.

Mark Birley apparently anticipated that his will might be challenged. Vanity Fair has learned that he wrote a letter to India Jane, to be disclosed with the will, in which he explained why he had done the unthinkable. Last June, shortly before he died, Birley—without notice and against the wishes of his family, close friends, and staff—abruptly sold his clubs for $207 million, a far higher price than anyone could have predicted. Even though his esteemed friend and adviser Sir Evelyn de Rothschild was willing to see if the offer could be matched, Birley went ahead and sold to one of those outsiders who are becoming so prominent in the acquisition of London’s high-end properties, the self-made millionaire Richard Caring, son of an American G.I. and a British nurse, whose fortune came from the garment trade in Hong Kong, and who has bought a number of the most fashionable restaurants in London, including the Ivy, Le Caprice, J. Sheekey, and Daphne’s.

Mark said in the letter that he had sold the clubs to protect them from Robin. “If Robin would have control of the clubs, the clubs ultimately would not be worth anything, and Robin certainly would not be looking out for his sister,” Miranda Brooks, a close friend of India Jane’s, explained to me.

There had been a previous will, by which Robin and India Jane would each have received 50 percent of the estate. However, in that will, Mark also left his valuable London house and property to India Jane. Peter Munster, one of Mark and his family’s closest friends and the executor of that will, says, “Robin was less than satisfied with anything other than a completely equal distribution.” Regarding the current situation, Munster adds, “Mark had reservations about Robin’s judgment in relation to his future expansion plans for the clubs and the risk that might have entailed. But he never would have brought Robin in if he hadn’t trusted him. The message is: There was no hate in the family. There was no vendetta.”

The Dodgy Detectives

Mark lost faith in his son after Robin used more than $400,000 from Annabel’s accounts to pay former London policemen claiming to be private detectives to supply him with what turned out to be totally false information about Robert Macdonald, in an investigation that Robin had instigated. In 2003, following a series of health setbacks—a knee operation, two serious falls, and a broken hip—that made it impossible for him to walk, Mark had brought Robin and India Jane into the business for the first time. “My sister and I got on very well and worked well together,” Robin told me in an exchange of e-mails. “Basically, I ran the company, and she attended to the look of the clubs.” By all accounts Robin did an excellent job of bringing in a younger, more with-it crowd to Annabel’s, which in the 90s was being described as a place where “the middle-aged meet the Middle East.” Robin had previously been running Birley Sandwiches, a chain he founded, which had shops in London and San Francisco. According to friends of Robin’s, Mark forced him to sell the two in San Francisco in order to concentrate on Annabel’s. (There are currently eight in London.) Then, in 2004, quite unexpectedly, India Jane, who was 43 and childless, became pregnant by Macdonald. Shortly after the birth of her son, who was a potential heir, Robin, suspicious of Macdonald and the situation, secretly gave the go-ahead to the former cops to find out whether India Jane’s boyfriend was out for her money. (At that time, India Jane did not have much income and Macdonald lived modestly.)

India Jane and Robin, Mark’s children, at Thurloe Lodge, their father’s London house, 2005.

“He was from a completely different social set … and I also think Robin did not want him in the business,” one of Robin’s friends said of Macdonald, adding that he was “a Canadian.” The alleged detectives provided Robin with tapes of women tearfully claiming to be wronged ex-lovers of Macdonald’s and saying he had fleeced them. Actually, the women were out-of-work drama students. The hired investigators also called on India Jane in the summer of 2006, frightening her when they insinuated that they had a lot of information about her. “It was highly improbable, unreal, and very, very unpleasant,” she told me. “It was very sinister. These people were thugs.” India Jane hired her own detective, who managed to track down one of the people involved. “He said it was Robin,” she told me. She subsequently listened to the tapes, which were “crackly and fuzzy,” she said. “I can’t imagine anyone being taken in by that crap.” She added, “It was very cruel. The intent was to ruin Robert Macdonald. I would then seem to be influenced by a famous financial fraudster.”

Meanwhile, that summer, David Wynne-Morgan, Mark’s longtime P.R. man and friend, who had started working with Robin at Mark’s behest, delivered a dossier of the material on the tapes to Keith Dovkants, a reporter at the London Evening Standard. The idea was to break the sensational story in the papers before Mark or India Jane knew about it. Wynne-Morgan said that, although he felt certain that Robin was sincere in his belief that his sister was being taken, he suggested that he tell his sister what he had learned from the investigators, but Robin demurred, thinking she would not believe him. India Jane says her brother told her the same thing later, when she confronted him. “But you were so infatuated,” she says Robin explained. “I believed I was acting in the best interest of my sister,” Robin informed me. “My father was too ill at the time to have any additional worries.”

In the course of fleshing out his story, Dovkants spoke to India Jane, and to Robert Macdonald—in the presence of lawyers Macdonald had to hire—and he was introduced by one of Robin’s investigators to two of the women on the tapes. After concluding that they were frauds, Dovkants notified Robin, who, according to the story that ran in the Evening Standard on October 13, 2006, met with the man who had supplied him with the tapes and also concluded that he had been duped. The story quoted Robin apologizing, saying he was in “absolute despair,” because he had believed he was, as he later told me, “acting in the best interests of my sister. She refuses to accept that, but it’s true.” I asked Dovkants if he felt he had been set up. “I am not going to tell you what I think the motive was [for giving the story to him]. It appeared to be an honorable motive at the time,” he said.

Macdonald received a cash settlement from Robin and had all his legal costs paid; he also got an official apology. So did India Jane. Characteristically, she never discussed the matter with her father. “I’m having a bit of a problem with Robin” was all she told him, she says. “Sort it out” was all he replied. It’s worth noting that nobody involved has sought to recover the $400,000 Robin paid the hired investigators. “Nobody wants to draw it all out,” India Jane said.

By then, Robin had also used hundreds of thousands of pounds more from the business for his own expenses, without telling his father or India Jane, who was all this time his partner in running the clubs. According to India Jane, she learned about the missing funds only when Kam Bathia, the finance director of Annabel’s, came forward to say he was planning to resign because he could no longer continue to dole out cash to Robin. Robin, however, is arguing that he had every right to take the money for his expenses because of a deal he had struck with his father—a deal, Robin says, his father later forgot he had made. Robin, according to the agreement, would halve his salary of more than $200,000 in exchange for 10 percent of the profits from Annabel’s. In fact, those profits had doubled since he started managing the business. The deal, an associate of Robin’s says, was contained in a letter that Bathia sent to Robin’s accountant. “I know nothing of such a letter, and Kam never mentioned it to me,” says India Jane. A person close to Robin summarized his position: “Robin’s not looking for charity. He’s not like a dog being given a bone from the table. He feels he’s created something and should be compensated. The will was changed on a false premise. He didn’t steal the money his father thought he did.” Bathia is not commenting.

In September 2006, after Mark learned about the money Robin had used, he threw him out of the business, and India Jane took over completely. The staff was told Robin was taking a sabbatical. On October 26, two weeks after the Evening Standard story hit, Robin married Lucy Ferry, who had formerly been the wife of Bryan Ferry, the lead singer of Roxy Music, with whom she had four sons. Mark was invited to the wedding but did not attend. India Jane, however, did. It was yet another rocky misstep for Robin in a father-son relationship long fraught with tension. “Robin desperately wanted his approval, and Pup’s approval was very spare,” India Jane told me. She added, “He was highly motivated, Robin, and his motives were dubious.”

Growing Up Birley

Adding to this dysfunctional stew is the perception among India Jane’s friends and Robin’s that their mother always favored her sons. “Annabel is unabashedly on Robin’s side,” someone close to Robin told me. “India Jane was always a Cinderella figure in the background,” explained Lynn Guinness, a longtime, dear friend of Mark’s; the young woman apparently did not marry well enough or behave to suit her family. India Jane refers to herself as “an old hippie.” Lady Annabel told me the relationship between her children is “not a subject I can discuss. As a mother, I want to keep myself out of it.” India Jane calls Lady Annabel and Mark “quite eccentric parents,” whom she claims to have “adored,” and Lady Annabel in turn describes India Jane in her memoirs as “wonderfully eccentric.”

“I was always being shunted around,” India Jane says of her childhood. At one point she had to give up her small bedroom so that her father would have more room for his boots and shoes. She later became a model for the painter Lucian Freud and began collecting antique erotica. Her first husband, Jonty Colchester, was an interior decorator whom she had met when she was an art student. Despite her pedigree, India Jane did not make much money as an artist, and her marriage to Francis Pike, during which she went off to India for a period, was, one of her friends told me, her attempt to discover “the discreet charms of the bourgeoisie.”

Robin was an ongoing source of sadness and guilt to Lady Annabel after she allowed him to enter the tigress’s enclosure at Aspinall’s. She tended him through the “years and years of surgeries” that could begin only when his face was fully formed, at 16. Despite his disfigurement, Robin never had any trouble getting girls, but he always bore the scars of his father’s neglect. “He got more overt attention from Jimmy [Goldsmith] than from Mark,” says a friend of Robin’s who is close to the family. “He felt that a betrayal.” According to Lady Annabel, “Robin and Jimmy did have a very close relationship. I don’t know whether that affected Mark. Mark never said anything.”

Robin, whom friends describe as impulsive and quick to anger, took up his stepfather’s cause when Goldsmith formed the Referendum Party, an anti–European Union offshoot of the Conservative Party. In the early 1990s, Robin supported Renamo, a far-right-wing political group in Mozambique. Robin also became convinced that Augusto Pinochet, the former Chilean dictator, was being wrongly hounded by Spanish prosecutors seeking to try him for human-rights abuses, and in 1998 Robin helped arrange for him to stay in a fancy estate outside London. In the 1970s, Goldsmith had gotten Robin a position in the U.S., with his Grand Union supermarket chain, and some years later Robin started his sandwich business there and in England. When David Wynne-Morgan delivered a letter of apology from Robin to Mark after the debacle of the tapes and suggested that Mark should forgive Robin, Mark in turn showed Wynne-Morgan a letter from 20 years earlier in which Robin had written, “I wish with all my heart that Jimmy Goldsmith had been my father.”

Today, Lady Annabel is 73. When she and Mark married, she was 19, the daughter of the Eighth Marquess of Londonderry. Her father, who did not much care for Mark, was on his way to drinking himself to death, after his adored and exceptionally beautiful wife, Romaine, died of cancer at 47. In her fascinating memoirs Lady Annabel recalls Mark’s first Christmas at Wynyard Park, her family’s vast estate. “Mark remained quite calm one evening when Daddy persuaded the local vet’s daughter to remove her clothes and dance naked on the dining-room table while he drank champagne from one of her shoes, held impassively by Robert the butler.”

Mark had grown up “unloved,” Lady Annabel told me. “I think he had a miserable childhood. Because of his childhood, he was a fairly closed-up person. There was a reserve that people couldn’t quite penetrate.” Mark’s New Zealander father, Sir Oswald Birley, was a painter of portraits of the British nobility. He was 50 when Mark was born, and unhappy with his striking and dramatic wife, Rhoda, whom Lady Annabel describes in her memoirs as a “bohemian hostess” with a large circle of artistic friends. Rhoda reputedly maintained an affair with a Scottish lord. Mark’s sister, Maxime, was a renowned beauty who later married Count Alain de la Falaise and became an international society figure and fashion leader. “Mark never stopped loving me,” Lady Annabel said. “He took on a paternal role and signed his letters Dad. I think he was absolutely incapable of being faithful. He was a serial adulterer. Like a butterfly, he had to seduce every woman.” Throughout, she added, he was always discreet. “He hid it very well, because he loved me, and he was heartbroken when I left.”

Mark graduated from Eton—where he showed that he had inherited his father’s ability to draw—in 1948, after which he lasted only a year at Oxford. “He was a sophisticated child,” his old Etonian housemate Michael Haslam remembers. “He told me once his ambition in life was to have a nightclub—I guess because it was very glamorous. He had this passion for glamour and good things in life.” He also had a penchant for getting people to do his bidding and make themselves look silly. “He would make me these horrid bets, like walking around the square in my dressing gown,” Haslam recalls. “I got quite a lot of the way before I got caught.”

During his National Service, from 1948 to 1950, Mark ended up with British troops in Vienna. According to his fellow serviceman Elwyn Edwards, “He was very amusing. He told me he had wanted to be in the Intelligence Corps, as his father had been in World War I, but the next thing he knew he was sent to camp Catterick, in Yorkshire, shoveling coal. His father was painting Monty [Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery] at the time and happened to mention it, so Mark was removed from Catterick and sent to us. He never made the Intelligence Corps.” Edwards says that Mark supported himself while in the service by selling “gentlemen’s white handkerchiefs,” which he bought at the military PX and then exchanged for dollars on the black market. “Even then he had the makings of a good businessman.”

A dining area in Annabel’s.

By the time Mark was 30, he was married with two young children, managing the first Hermès store in London. In 1961 he was approached by John Aspinall, who was planning to open the Clermont Club in an attractive Palladian house designed by William Kent at 44 Berkeley Square (later made notorious as the locale frequented by Lord Lucan before 1974, when he killed his children’s nanny—having mistaken her for his wife—and then allegedly escaped the country with the help of his very rich friends from the club). Aspinall asked Mark if he wanted to start a nightclub in the basement. “He had to go cap in hand to raise money for Annabel’s, but I was always certain of success because of the way he did up houses,” Lady Annabel said. The founding members were charged five guineas ($14) annually to belong, and many of them continue to pay that fee today. Annabel’s now has 9,000 members, each of whom pays up to $1,500 in annual dues. Thus, Mark was able to attract those who would not only pay annual dues—even though they might not eat there more than a couple of times a year—but also pay top prices for the drinks and dinner served. In his eulogy at Mark’s funeral, Peter Blond, a fellow old Etonian, remembered running into Mark on the street before the opening and being taken to the unfinished basement: “In the gloom of the cellar, lit only by a string of naked lightbulbs looped around a vaulted ceiling, he outlined his plans for what was to become the most famous nightclub in the world.”

From its overcrowded opening night, Annabel’s transformed London social life. Some of the old snobbish clubs, such as the 400, in Leicester Square, which required dinner clothes, were already on their way out, and Mark’s more raffish set didn’t have many places left to go to, apart from the Milroy, on Park Lane, a private establishment with a nightclub upstairs called Les Ambassadeurs, and Siegi’s, on nearby Charles Street, which had a back room for gambling. Soon Mark was presiding over his own private zoo of social lions. “Annabel’s quickly became the place to go,” David Metcalfe said. Men could gamble half their fortune away upstairs and pop down for a drink or a dance. European royalty and dowagers would rub elbows with, in Wynne-Morgan’s phrase, “the right sort of young.”

The Taste-Maker

Mark Birley was there every night, watching the good and the great mingle, couple, and uncouple. Part of his genius at Annabel’s was to create a dramatic ambience that felt both elegant and cozy, a series of marvelously scented small sitting rooms with comfortable sofas and big pillows, a bar on the side and the dance floor at the back, with an eclectic mix of witty cartoons and dog paintings on the walls. Nina Campbell, the young decorator he took on, who stayed with him through every establishment, told me, “As a woman, you could go to Annabel’s and they would look after you. The staff would make you a special drink. It was like a great big wonderful family—you felt embraced as you arrived.”

Annabel’s was certainly a great big wonderful family for one special crowd, and Birley accrued major glamour and social power. He never allowed the press inside unescorted, so nothing got leaked and celebrities were left alone. “In the beginning, everyone vaguely knew each other, which was not the case thereafter,” says Mark’s old friend Min Hogg, the founding editor of The World of Interiors. “It was a terribly good place for ‘the gang’ to meet each other.” She adds, “You were attended to like mad, in surroundings that could be someone’s house.”

Throughout his four decades in business, Birley watched every penny but spared no expense. He spent a year making trips to Brazil in order to create three weeks of Carnival at Annabel’s, complete with samba musicians and topless showgirls. Valentino staged fashion shows at the club, and there was a New Orleans fortnight with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band and food from Antoine’s, as well as a Russian fortnight, when Viscount Hambleden came every night and danced on the tables in Cossack boots, while Gypsies warbled “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ ” in Russian.

On the gala opening night, Annabel met Jimmy Goldsmith, who was already a widower with a child and a remarried husband with a girlfriend. By 1965 their romance had taken flight. “Jimmy was such a larger-than-life figure he just swept me off my feet,” Lady Annabel said. “I didn’t mean it to go as far as it did.” In the British upper-class tradition, the Birley boys were packed off to boarding school when they were eight, but India Jane was allowed to stay home until her teens. As a result, she saw more of her father than her brothers did, and he was always interested in her talent. When India Jane entered a series of art schools, he continued to be very supportive. Growing up, India Jane said, she was not particularly aware of her family’s unconventional arrangement and structure. “When little children go to bed, they don’t know what their parents are doing.” Pup, she recalled, was around “for tea. He was a familiar figure when I was little.”

Robin was a different story. “I think what Robin needed was someone to put his arm around him and tell him he would be all right,” a friend of Mark’s said. “Mark couldn’t do that. It was contrary to his whole nature. When Annabel went off with Jimmy, Jimmy was the complete opposite. He was very good at wearing his emotions on his sleeve, and he built Robin’s confidence up. Robin and Mark had a sort of love-hate relationship.”

An interior at the Bath & Racquets, which Birley opened in 1990.

Mark lavished his attention on his growing business. “You were buying into a world: Mark Birley’s life and how it should be lived,” says his onetime number two Gavin Rankin. “Mark completely changed the face of civilized dining in London—revolutionized it.” With Mark’s Club, which opened after Mark bought out Siegi’s, in 1973, Rankin says, “he took the concept of an English men’s club, turned it on its axis, and made it far nicer than any gentlemen’s club.” In 1990, when Mark could not find a health club to meet his requirements, he opened the Bath & Racquets, complete with onyx-lined shower rooms. Harry’s Bar, which he opened in 1979, is still one of the most elegant and expensive restaurants in London, while George, which opened in 2001, is far more casual and attracts a younger crowd. “People would always pay for the frills,” Rankin says, “and if you could be unassailably the best, then the market was yours.”

All the clubs and restaurants are located in Mayfair near Berkeley Square. Although Birley traveled to Hong Kong, Brazil, and New York with the stated intention of duplicating Annabel’s, he really just wanted “to see what was going on,” says Wynne-Morgan. “He never started anything he couldn’t walk to.” According to Willie Landels, who did graphic design for Mark, “Having lunch was one of his great occupations. He lunched mainly at the clubs, and one ate much better when one dined with him, because all would try to outdo each other trying to please him. He was very spoiled that way.”

Staff and Dogs

The indispensable element that permeated all of Birley’s establishments was a carefully chosen staff, who tended to stay for years and thus could be counted on not only to greet members by name but also to know their likes and dislikes. “Mr. Birley was ahead of his time,” says Alfredo Crivellari, the former manager of Annabel’s, who worked there for more than 35 years, until his retirement at the end of 2007. “He headhunted earlier than anyone else. He would go round and find the best.” When Birley interviewed Crivellari for a waiter’s job, he asked only two questions. Are you married? Yes. Do you have a mortgage? Yes. “ ‘You start work on Monday,’ he said. He knew I was committed.” Although Birley was “slow to bless and quick to chide,” Rankin said, he was also keenly aware of the staff’s importance. “Everyone was made to feel vital.” He once revoked the membership of one of his best customers at Annabel’s because the man had been rude to a waiter: “I can always replace you, but not a waiter.”

In the manner of a feudal lord, Mark took care of his own—provided doctors, paid for weddings, gave extravagant gifts, wrote gracious notes. When a waiter left to go back to Thailand to begin a restaurant and the business failed, Mark went to Thailand, paid his debts, and brought him back. No one was ever told to retire, but after they stopped working for him, he would pay for a taxi to bring them back for one hour a day so that they would have to get dressed and have a good meal. Bruno Rotti, the manager of Mark’s Club, said that when he stopped working full-time Mark had a small bronze bust cast of him and kept it on a table at the club, “ ‘so there will always be a Bruno,’ Mr. Birley told me.”

The motto for Birley’s staff was “It shall be done.” “Quality is only met with precision,” said Sir Evelyn de Rothschild. “We couldn’t do anything without his notice,” said Rotti. “ ‘That young lady’s hair has grown a bit too long—have it cut or put it up. It’s a bit untidy.’ ‘There is a basket left out in gents.’ He was a perfectionist.” David Metcalfe added, “If he was there, they always knew it—he’d always watch and not hesitate to comment, often in a very caustic way. ‘I would have thought by now … ’ ‘I would have thought the very least you could do … ’ ‘I’d be rather grateful if … ’ That meant he was furious.” Mohamed Ghannam, a barman at Annabel’s who functioned as Mark’s butler, concurred: “Such sarcastic remarks he made—you’d never forget the bollocking and you’d never do it again.”

Hostesses trembled in Birley’s presence. “People were very nervous to have him stay or eat,” Landels said. “He was quite severe. I remember once we stayed somewhere and in the middle of the morning he told the hostess, ‘The way the breakfast tray was laid was very bad. The napkin must be very white and very starched. Orange juice should be served in glasses of this shape, not that.’ ”

Despite the scowls and judgments, Mark had many friends who were awed by his taste and adored him. “He was always coming to the rescue of people,” said Lynn Guinness. “He had a very dry sense of humor, a sense of the ludicrous. He was a marvelous man in so many ways.” Metcalfe added, “On a good day, when Mark wished to be, he was charming. But charming and having charm are completely different. He was very selfish and self-involved.” Lady Annabel said, “It’s quite difficult to live with a perfectionist, but the thing is, life with Mark was fun. Our breakup was because of Mark’s infidelities, not because I fell in love with Jimmy.”

India Jane calls her father “the funniest man in the world.” Although she was clearly his favorite and visited him daily, Mark himself seemed to take his greatest pleasure outside his family. “He was not the sort of person to have a woman make him happy,” Mohamed Ghannam explained. “He was very happy with his dogs and working with staff.” Ghannam, 58, spent most of his life with Birley. He was 18, one of 11 children, when he was sent from Morocco, through the recommendation of a member of the English Parliament, to train to be a waiter at Annabel’s. When his visa was up, after one freezing month, he wanted to go home, but Birley’s secretary tore up his return ticket and enrolled him in school. He would come in to work at night. Mark paid his rent for seven years. Early on, Ghannam recalled, “their Christmas was coming, and Mr. Birley wanted me to spend it with them, with Lady Annabel. And from then until now I spend Christmas with the whole family.”

Ghannam, married, with three daughters who have all attended college, is perhaps the ultimate family retainer. “Mr. Birley taught me how to dress, how to behave, how to talk to princes, dukes, and princesses,” he said. “Once, I made a gin martini for the Queen.” He did not take one holiday during the last 15 years of Birley’s life, but he would accompany him to Spain, Morocco, or wherever he spent his vacation. Every Sunday he would go to his employer’s fashionable house, Thurloe Lodge, across from the Victoria and Albert Museum, just to make a special cocktail for Mr. Birley. Mark was also pampered on a daily basis by his caregiver, Elvira Maria, and her niece. His staff saw him more than his family did. According to Ghannam, “He said his dogs came first and his family second.”

Toward the end of his life, when he lived on one floor and was unable to walk, Birley let George, his black Labrador, have the bed with the comfortable mattress, and he slept in a reclining chair next to the bed. His other dog, Tara, was an Alsatian. “I used to talk to George the dog in order to bring Mark back to life again,” Sir Evelyn de Rothschild said of visiting Birley in his last months.

Lady Annabel said she was the one who introduced her first husband to dogs. “I come from a doggy family,” she told me. “I’m writing a book about Mark and his relationship with dogs. Everybody knows about the clubs and his love life, so that is the angle I’ve taken. He adored dogs. He told me, ‘I go to these dinners, and I sit down and think, God, I wish I was in my lovey, comfy bed with my dogs. There is nothing I like better.’ ” Lady Annabel keeps her own dogs in Colefax and Fowler duvets, and she has written an entire book about one former pet, Copper, a mixed breed, who she swears used to ride the bus by himself and visit pubs and hold his paw up to cross the road. India Jane provided the illustrations.

According to The Daily Telegraph, Mark left more than $200,000 in his will to the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, and during his lifetime he had a beloved mutt named Help that he had rescued from the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home. Help did not care for two Saint Bernard puppies Mark bought, so they were sent to Austria to be there for him when he skied in the winter. “Mark thought Saint Bernards looked good in the mountains,” Wynne-Morgan said.

Once, the actress Joan Collins was invited to Mark’s house for a small, fancy lunch. After she was seated, she screamed and pushed her chair back. Under the table, Blitz, the huge Rhodesian Ridgeback, had been licking her ankle. “Take that dog out of here!” she cried. Mark gingerly coaxed Blitz out from under the carefully laid table, and the dog lay down in the hallway, his head between his legs, looking miserable. After Mark finished the first course, he excused himself and went out to apologize to his pet. “I’m so sorry, Blitz,” he was overheard to say. “That bitch will never set foot in this house again.”

End of an Era

No one wanted Mark to sell the clubs. His friends and family all implored him not to. Some, including David Tang, the Hong Kong mogul, also asked him to forgive Robin. Tang reported that Mark said, “Nobody talks to me about Robin—I don’t like it.” Mohamed Ghannam got away with more than most: “He’s your son, Mr. Birley—doesn’t it matter? It’s only money. My God, you lost Rupert—you’re not going to lose Robin just because of a stupid mistake?” Robin was Ghannam’s boss at Annabel’s, and Ghannam and others were ordered to report daily to Mark on how things were going. Ghannam thought Robin worked very hard and did an excellent job. “Robin has a heart of gold,” he told me. “He does whatever you ask.” Robin said, “I loved the clubs, and I believe I had a real feeling for what my father created.” But it was too late.

The buzzer at Mark’s Club.

Ghannam was pushing Mark in his wheelchair in Marrakech last June when the moment came. Mark had gone to Morocco to buy a house on a property developed by his friend Lynn Guinness and his former son-in-law Francis Pike. India Jane and Miranda Brooks were also visiting. The house was nearly ready, but Mark suddenly started demanding last-minute changes. According to Ghannam, they all told him it was not possible to do those things. Ghannam said, “I tried to tell them, ‘Stop! Don’t tell him what to do.’ Because I knew immediately, That’s it. That’s the end of this house. He only said, ‘Mohamed, it’s time for lunch.’ ”

Then, instead of calling the lawyers from Casablanca, who were ready to close on the property, Mark summoned Richard Caring’s lawyers from London, who arrived the next day by private jet. Caring told me he had been trying to buy the clubs for more than a year. “It was a bit of a shock when it really happened.” Mark had already grilled Caring thoroughly and had gotten him up to a great price. “If you believe in quality, top-of-the-pile sparkle,” Caring said, “you don’t do better than this.” India Jane was beside herself. She had thrown herself into running the clubs since Robin’s departure, and her father had said nothing to her about any sale. “I really did cry and cry, and I am not a crier,” she said. When Sir Evelyn de Rothschild suggested countering the offer, Caring reminded Mark that they had a deal. After the sale, Lady Annabel asked Mark to give each of the children $10.3 million, but Mark reportedly just rolled his eyes. When asked what he planned to do with all his money, he replied, “I’m going on a cruise.”

Mark had never discussed his will with his children. India Jane and Robin, once easygoing siblings and partners who would play jokes and have food fights, actually saw each other when Robin came around to collect some suits and ties of their father’s the day before India Jane heard that her brother was contesting the will. “It came out of the blue,” she told me. “I have absolutely no animosity towards Robin,” whom she described as a “wild, wild creature.” She added, “Sometimes I wish he’d go live in the Congo forever. It’s all so unnecessary. At times it makes me want to weep.”

The big question now is: How can Robin possibly break the will? It will be very difficult. Mark made sure that a doctor came from London to examine him for his mental competency at the time of the sale, and the doctor said he was compos mentis. (Robin’s side argues that it wasn’t his regular doctor.) The same procedure had occurred earlier, when Mark made his will, which leaves India Jane his house, last evaluated at $35 million, and allows her to live off the income of the trust until her son is 25. Thus, the trustees, not India Jane, have final say. “People think it is something I am in control of. I’m not,” India Jane said.

According to Miranda Brooks, India Jane told Robin that, if he would wait for the period of probate to be over, she would try to help him if she could. Peter Munster says, “The will cannot be changed unless there is evidence. The reason is that a minor is involved, and he is the main beneficiary. If the will were to be changed, the trustees would have to go to court. If it would be changed to the detriment of a child, the court would be loath to change anything.”

When Mark was operated on for his knee, Lady Annabel said, “he drank quite a lot and mixed it with painkillers, and he kept having falls.” She said he fell two weeks after the operation and fractured his hip. And he would not do physical therapy. “That’s when it all began,” she said.

During the time Birley was drinking and taking painkillers, he apparently was disoriented, his memory was impaired, and he was not himself. “He was taking a whole cocktail of medications,” Lynn Guinness explained. “When they changed that, the confusion stopped.” Guinness said that every morning when he was with her, he would get the figures of Annabel’s take from the night before. “He got this incredible deal from Caring. How does someone off his head manage to do that?” India Jane asserted, “My father was right on the button” regarding his business. His caregiver, Elvira Maria, a beneficiary in the will, agreed: “Mr. Birley was never confused about business or money.” I asked her if what I had been told was true, that shortly before he died he had spoken of a rapprochement with Robin. “He never mentioned that,” she replied.

Robin’s partisans disagree about Mark’s mental state, and they feel that Robin needs to be more fairly compensated for giving up his San Francisco businesses. “[Mark’s confusion] was bad for a few months, particularly at the time that Robin’s part in the investigation of India Jane’s lover came to light,” says David Wynne-Morgan. “He had short-term-memory loss until he died.” Shaun Plunket, a cousin of Lady Annabel’s who is now married to Andrea Reynolds, Claus von Bülow’s former companion, phoned Mark frequently from upstate New York. “He was losing it for the last year, and I detected it on the telephone,” he told me. “He was not living a happy life at all.” Peter Munster disputes that: “If lawyers were to call witnesses, there are several people, such as myself, who would stand up in court and say that Mark knew precisely what he was doing.”

Mark was making plans to visit Lynn Guinness again in Morocco the night before he died of a massive stroke, on August 24. India Jane was with him at the end. His death came as “a terrible shock” to Lady Annabel, who said, “I thought he’d go on for years, he was so primped.” Of the sale, she said, “I think maybe in his heart he felt that nobody could run it like him.”

India Jane arranged the funeral, at St. Paul’s church in Knightsbridge, which was attended by Margaret Thatcher, Prince and Princess Michael of Kent, the Duchess of York, and staff from as far away as Australia. The most dramatic moment came at the end. “When the coffin was carried from its place before the altar towards the door of the church,” said Peter Munster, “it was followed by Mark’s driver, Don, leading his two beloved dogs, George and Tara, whilst a piper played a lament.”

For now, probate is frozen, so the real value of the estate is not yet determined. “Mark would be horrified at the publicity,” Lynn Guinness says, and India Jane, who has a new romantic interest, a rare-clocks dealer, swears that all she wants to do is “play with the baby and feed the kittens. I am very, very boring.” Lady Annabel speaks frequently with both Robin and India Jane. “We talk all the time,” India Jane told me. “She prattles on about dogs and we don’t talk about it.” And what if the case ever gets to court? Miranda Brooks says, “Jane’s got no illusions about that. If her mother has to appear in court, we know who she’ll favor.” Does India Jane really think her mother would testify for Robin against her? “I don’t know,” India Jane says, “and I really do mean it. I can’t even imagine. It’s a bit of the unthinkable.”

No Comments