Vanity Fair – September 1995

“I love Britain . . . Ethics and morals count in Britain like nowhere else in the world.”

-Mohamed Al Fayed, 1985.

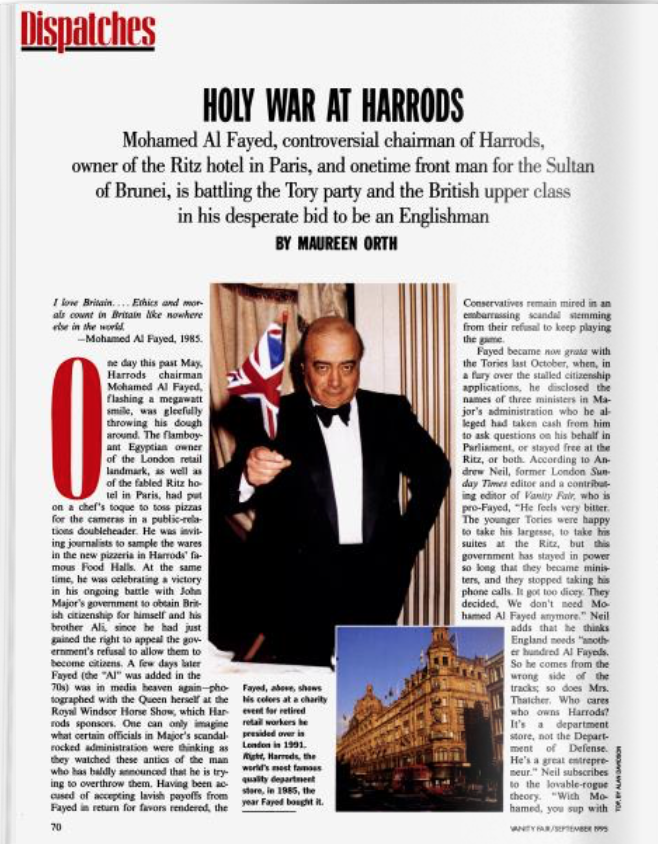

One day this past May, Harrods chairman Mohamed Al Fayed, flashing a megawatt smile, was gleefully throwing his dough around. The flamboyant Egyptian owner of the London retail landmark, as well as of the fabled Ritz hotel in Paris, had put on a chef’s toque to toss pizzas for the cameras in a public-relations doubleheader. He was inviting journalists to sample the wares in the new pizzeria in Harrods’ famous Food Halls. At the same time, he was celebrating a victory in his ongoing battle with John Major’s government to obtain British citizenship for himself and his brother Ali, since he had just gained the right to appeal the government’s refusal to allow them to become citizens. A few days later Fayed (the “Al” was added in the 70s) was in media heaven again–photographed with the Queen herself at the Royal Windsor Horse Show, which Harrods sponsors. One can only imagine what certain officials in Major’s scandal-rocked administration were thinking as they watched these antics of the man who has baldly announced that he is trying to overthrow them. Having been accused of accepting lavish payoffs from Fayed in return for favors rendered, the Conservatives remain mired in an embarrassing scandal stemming from their refusal to keep playing the game.

Fayed became non grata with the Tories last October, when, in a fury over the stalled citizenship applications, he disclosed the names of three ministers in Major’s administration who he alleged had taken cash from him to ask questions on his behalf in Parliament, or stayed free at the Ritz, or both. According to Andrew Neil, former London Sunday Times editor and a contributing editor of Vanity Fair, who is pro-Fayed, “He feels very bitter. The younger Tories were happy to take his largesse, to take his suites at the Ritz, but this government has stayed in power so long that they became ministers, and they stopped taking his phone calls. It got too dicey. They decided, ‘We don’t need Mohamed Al Fayed anymore.’ ” Neil adds that he thinks England needs “another hundred Al Fayeds. So he comes from the wrong side of the tracks; so does Mrs. Thatcher. Who cares who owns Harrods? It’s a department store, not the Department of Defense. He’s a great entrepreneur.” Neil subscribes to the lovable-rogue theory. “With Mohamed, you sup with a long spoon.” Film producer David Puttnam, who got half of the $6 million to produce the 1981 Academy Award winner Chariots of Fire from Fayed, agrees. “Mohamed is somebody who works on an old-fashioned system: favors done, favors received… For 10 or 12 years the government said, ‘Anything goes. We live by our own ethics.’ … What I find unfair is that what Mohamed’s accused of is an everyday occurrence in London”.

When I met Fayed last fall, in his heavily scented office at Harrods, which he shares with a giant teddy bear of the sort that is for sale on the fourth floor, he told me, “The more good you give, the more angels guide you, protect you. The more terrible you are, the more dishonor for you.” Since then, the angels have more or less sat on the fence. The government’s rejection in February of the Fayed brothers’ petitions for citizenship-without explanation-was a stunning rebuff to someone who constantly invokes the importance of loyalty and respect. But if the affidavit of a onetime government chauffeur who allegedly read a privileged Conservative Party memo and overheard party whips discussing Fayed and his case in derogatory language is to be believed, the decision to grant him citizenship would have been “political suicide”. It appears that the Establishment has made up its mind. Fayed can make numerous highly publicized donations to charities and play the jolly merchant prince for the press as much as likes, but those he wants most to impress-the British upper class-have decided to give him the cold shoulder. “Nobody quite accepts him,” admits a friend of his, former Daily Express executive editor Alan Frame. “We’re still a class-ridden society. He sponsors lots of things involving the royal family, and he’s still not accepted.”

Ironically, 10 years ago, when Fayed purchased Harrods, he had the Conservative government in the palm of his hand. Since then, many members of Parliament have come to realize what a dangerous man he is to cross. Behind his bubbly facade, Fayed maintains an elaborate security apparatus and bugging system, wields the considerable advertising budget of Harrods to intimidate the press, hires and fires at will, and is perhaps the most litigious man in England. A decade ago, with the acquiescence of Margaret Thatcher and the Conservatives, he pulled off a coup to buy Harrods that was breathtaking in its audacity. Last fall, when he unleashed his “cash for questions” scandal, he aimed at nothing less than attempting to topple Major’s government. As he later told me, “I make revolution.” Fayed sees himself as the victim of the worst British snobbery. “The devastating thing is the class system, created of people who think they are above the rest of the human race. They think they can shit just on anyone,” he told me. “They think I’m a wog.”

On the Continent, Fayed’s long-sought-for status is assured. On display in his office is a citation from the Italian government, and France gave him the Légion d’ Honneur after he restored not only the Ritz but also the Duke and Duchess of Windsor’s former home in the Bois de Boulogne. On the far wall are four “warrants” to supply boots and saddles, housewares, linens, and other goods to the British royal family. Harrods, after all, is the second-greatest tourist attraction in London after Big Ben, and Fayed has announced that when he dies he wants to be mummified and entombed on the roof.

For two-plus decades, Mohamed Al Fayed, who is 66 but says he’s 62, has lived in London as an unabashed Anglophile guided by a simple Middle Eastern motto: To give is to receive-whether it be presents, favors, or influence. Charming in public, he is privately phobic about germs and fanatical about loyalty. Surrounded by bodyguards, he often conducts business on a cellular phone in a tent pitched on the lawn of his country estate in Oxted, Surrey. His fervent love for Britannia goes hand in hand with his strings-attached mode of generosity: large charitable contributions, political payoffs, Parisian junkets for journalists, toys for their children, and Harrods Christmas baskets to half of Debrett’s Peerage.

Although Fayed lives luxuriously, he carries a staggering amount of debt and spends prodigiously. The losses on the Ritz through 1993, for example, totalled nearly 1.2 billion francs ($212 million). Nevertheless, Fayed prides himself on owning world-class status symbols and maintaining the highest level of service.

Generations of English schoolboys have gotten their hair cut at Harrods, which will order anything from a castle to a Learjet for grown-ups. But before Fayed bought the vast Knightsbridge store-the largest department store in Europe-it was a fading institution, where toilet paper was sold on the first floor. Fayed has poured many millions into restoration, installing the “Room of Luxury” and the Egyptian Hall, with his own face carved on the sphinxes around the molding. He has upgraded the toy department, opened restaurants, and recently, as the British retail market has sagged, introduced a more affordable line of Harrods private-label apparel.

At the Ritz-which was founded by the master hotel manager Cesar Ritz in 1898, and which has catered to Garbo and Hemingway, Rockefellers and royalty-no expense has been spared; indeed, the red ink has flowed to keep up the 187-room establishment as the finest hotel in the world. Leaky pipes were tom out, the antiquated heating system was replaced, every room was redecorated. Today, guests can luxuriate in theme suites – the Cocteau, the Chopin, the Chanel. The Imperial Suite, overlooking the Place Vendome, costs more than $10,000 a night. Fayed has also added an underground swimming pool, a culinary school, and a nightclub for the Ritz clientele: “people who care for nothing but the best.”

And just in case a foreign visitor might not intuit the level of aspiration which seeks to become reality here, Harrods’ dashing director of public affairs, Michael Cole-his master’s voice-is superb at interpreting. Tall, handsome, silver-haired, and silver-tongued, the one-time BBC-TV royal reporter-who lost his post after leaking the Queen’s 1987 Christmas message during a festive holiday lunch-is quite a contrast to the short, balding Fayed, who, for all his ambition, struggles to read and write the language of his adopted land. Theirs is a symbiotic relationship: the one knows how to parse the one who holds the purse.

Cole is a magician of royal spin. The first day I spoke with him, he introduced me to Harrods’ most beloved veteran, an elderly green-suited messenger who delivers to all the little royals gifts from “Uncle Mohamed.” Cole declared, “If it weren’t for Rodney, the princes might not even know there was a Father Christmas!” Another time, Cole called me from his car phone and began speaking as if he were back filing a BBC report: “At a £200,000 [$312,000] party at Spencer House given by Lord Rothschild but paid for by Gulfstream, the Princess of Wales arrived, stunning in a beaded dress. She ignored everyone else and went straight up to Mohamed and said, ‘I didn’t know you were rich enough to have one of these planes!’ Mohamed said, ‘At your disposal, whenever you wish.’ Diana is so easygoing with Mohamed… Mohamed is not one of those who’s overwhelmed by her. They spark off each other very well.”

Cole encouraged me to call other friends of Fayed’s, naming General Norman Schwarzkopf, New York Times chairman Arthur “Punch” Sulzberger, financier Ted Forstmann, and Estée Lauder, whom Cole claims Mohamed bounces on his knee. Many believe Fayed would like someday to be Lord Al Fayed. “I don’t want that,” Fayed protested when I spoke with him. “But they didn’t also say thank you for everything I have done. It’s the opposite. They just could shit on me, everyone.”

Fayed was perched restlessly on the edge of his seat, wearing ankle boots with zippers on the sides and a plaid sport coat. “I did it to take my revenge, to show people who really runs this country, what quality they are… These days it’s only the trash people.” He was referring to his disclosure last October of the names of ministers who he claimed had received favors from him. When Fayed made these charges, British newspapers reported that he might bring down the government. Several weeks before the “sleaze” scandal broke, Major had received a warning-via a newspaper editor-of Fayed’s allegations against his government, and was told that Fayed wanted a meeting to discuss withdrawing or revising a report released in 1990 by the Department of Trade and Industry (known as the D.T.I. report) which accused Fayed of lying about his past and making fraudulent claims about his fortune.

When a Member of Parliament asked Major if Fayed was attempting to blackmail the government, Major appeared to give credence to the charge by saying that the matter had been referred to the director of public prosecutions for investigation. Fayed was later cleared of any wrongdoing and demanded an apology, which has not been forthcoming. Today, Fayed continues to insist that the British government was indeed for sale-like selling me ice cream,” he told me. Michael Cole quickly rushed in: “Mohamed said, ‘I’m a merchant. They came to me. I sell ice cream. I sell sausages. They came selling MPs.’ ”

“What he is, he’s still an Arab street trader,” says Alan Frame. “He still believes he can buy anybody. He really does believe that if enough government ministers-indeed, enough journalists-are given enough fine gifts, stay in his hotel enough times, get hampers at Christmas, he’ll get what he wants.”

Fayed’s fury was stoked, he says, because he was given assurances that his and his brother’s applications would pass. The government calls that claim “rubbish.” The British petition for citizenship requires, among other things, that the applicant be 18 or over, have up to five years’ residence, and be of sound mind and “good character.” Regarding character, the British civil service is bound to respect the conclusions of the D.T.I. report, which was written by two prominent “inspectors.” Sir Henry Brooke, who is now a High Court judge, and Hugh Aldous, who is now the managing partner of a prestigious accounting firm. When Fayed and his two brothers, Ali and Salah, suddenly burst onto the scene in 1984 to buy Harrods, they said they came from an old, rich Egyptian cotton-growing family. The report later documented that Fayed was actually the firstborn son of a humble schoolteacher and grew up in the slums of Alexandria. The report also claimed that the Fayeds were not remotely wealthy enough to have us their own money to put up the $700 million cash bid to buy House of Fraser, Harrods’ parent company, a vast department-store chain extending from Scotland to Scandinavia. The report suggested that the money had come from the Sultan of Brunei, without his knowledge. Fayed maintains that the money was his.

According to Fayed, the applications for citizenship were prompted largely by the discomfort his brother Ali feels every time he must part from his English wife and three English-born sons to pass through British customs from the “aliens” line. (Mohamed is married to a Finnish woman, with whom he has four children, aged 8 to 14.) Fayed blames Home Secretary Michael Howard, under whose jurisdiction the applications fell, for creating a convoluted conspiracy against him. So far he has failed to back up the charges with any hard evidence, but his wrath encompasses the whole ruling elite. “I can still hear the prejudice, the racists at the core of the upper class. They call themselves the so-called Establishment.”

“The people he turned on were his friends-nobody quite knows why he did it,” says Lord McAlpine, a long-time confidant of Margaret Thatcher’s who was Conservative Party treasurer and who used to visit Fayed regularly. Fayed says that McAlpine accepted £250,000 ($367,000) in political contributions from him between 1985 and the election year of 1987, when it was announced that the D.T.I. was going to investigate Fayed. British law does not require disclosure of political contributions from individuals. Lord McAlpine acknowledges several Fayed donations to Conservative causes but not specific amounts, adding, “He would have been sent a thank-you note and a receipt from me. Ask him to show you the receipts.”

Alistair McAlpine responds to the Fayed brothers’ charges of snobbery and racism by saying, “Then why do they want to live here? I feel very sympathetic towards Al Fayed. I feel he’s been very badly treated, but it’s largely their own fault. They get misunderstood; they try too hard. I can’t fathom why they want British citizenship.”

“Do you know what ‘wog’ stands for?” asks Lord Wyatt, another Thatcher confidant who has attacked Fayed in print. “Wily Oriental gentleman.” Woodrow Wyatt calls the whole business “absolute nonsense.” He says that Fayed’s attacks are a result of his losing his case in a unanimous decision last September at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg-the final stage in a futile attempt to have the D.T.I. report erased. “The government said no, and the Court of Human Rights said no, and it sort of drives them dotty. It remains a slur on their character.”

“The Fayeds dishonestly misrepresented their origins, their wealth, their business interests and their resources: the D.T.I. report states early on. More than 700 pages later, it ends by saying, “The lies of Mohamed Fayed and his success in ‘gagging’ the Press created …a new fact: that lies were the truth and that the truth was a lie.” A vehement denial issued by Fayed at the time said that the report was “worthless” and “shocking.” The fact that no action was ever taken against him by the British government, he says, proves that there was no wrongdoing. His enemies, on the other hand, charge the government with a massive cover-up to protect him.

The D.T.I. investigation was ordered in 1987, a full two years after Fayed’s petition to buy Harrods was hastily waved through by the Thatcher government in 10 days without careful scrutiny. Fayed believes the probe came about through the ceaseless, vengeful efforts of the man he had outwitted to win the store, the equally eccentric mega-tycoon Roland W. “Tiny” Rowland, then chairman of the conglomerate Lonrho, which is based on mining and agricultural interests in Africa. Rowland hired private detectives to comb the world to uncover whatever incriminating facts they could about Fayed. Using the best investigative reporting that his money could buy, including the resources of his own newspaper The Observer, he flooded the Establishment with a series of detailed reports depicting his rival as a liar who had bought off the government and a con artist who had used the Sultan of Brunei’s money to buy Harrods.

Fayed’s life story is right out of Aladdin or Ali Baba. The characters include global fixers and dealers who think nothing of trying to destabilize countries, seduce the world’s wealthiest man, sue whomever whenever, buy the press, and wage private wars. It takes place in the habitat of the offshore superrich, complete with yachts and jets, where friends become enemies, enemies become friends, and the enemy of my enemy is my friend. Truth here is rather like a Platonic ideal-it must remain an abstraction.

Michael Cole, however, continues to define his boss as a wronged and selfless hero who has been consistently victimized. “He thinks he did the right thing for this country. He has a very developed sense of morality. Of course, he wouldn’t call it that,” Cole says. “He’s so used to being slapped in the face he doesn’t even think about it. …All he’s interested in is his good family name and reputation, his children, and his own health and happiness. He doesn’t look for praise. He has his own foundation to relieve real suffering-he thinks it’s his sacred duty. He has a very personal relationship with his God.” Cole sighs. “I sometimes think this is a charity with a business attached.”

“Enter a Different World,” Harrods’ long-time slogan beckoned. With Mohamed Al Fayed at the helm, it is a darkly suspicious world with laws unto itself. Fayed, who spent hundreds of millions of dollars refurbishing Harrods, has visibly tightened security and now even sells the display windows to vendors. He recently unveiled plans for a new hotel across the street, and he’s designing a nearby Harrods village on the Thames. But in the 10 years of his ownership, Fayed has had five managing directors; he is embroiled in numerous cases brought for unfair dismissal, and he is accused of everything from racial discrimination and enforced H.I.V. tests to bugging employees’ phones and maintaining a fleet of secretaries – “some who type and some who don’t,” according to a former employee. It is, says former Harrods deputy chairman Christoph Bettermann, “management by fear.”

Fayed has a personal security staff of 38-two teams that alternate, one week on, one week off, at his residence at 60 Park Lane, at his country house in Oxted, where his family lives, and at his castle in Scotland. His “close-protection team” consists of 8 or 10. One assumes that the millions of dollars this security costs and the level of his apparent paranoia, which extends to wearing only clip-on ties so that he cannot be strangled, must mean that Fayed’s life is under constant threat. Not so, according to a half-dozen former guards I interviewed, who say that his security is mainly for show.

“He modeled himself after whatever the prime minister of the day used,” says Bill Dunt, a guard for three and a half years, who says he was fired after being accused of speaking to a female guest and who accepted an out-of-court settlement of his unfair-dismissal suit. “If the prime minister used a Rover fastback, he would. If they changed to a Ford Scorpio, he’d change. It’s part of trying to get into the Establishment.” Like the U.S. president, who has a military aide to carry nuclear-launch codes in a soft black leather bag, Fayed had guards travel back and forth between Switzerland and England with his hard silver box, which contained unspecified floppy disks.

The guards point out that real protection was impossible, because they were rarely armed, they were not allowed to ride in his car with him, and he refused to tell the guards riding in the backup car where he was going. Anyway, nobody was going to take a bullet for “the fat bastard,” the guards’ cruel code name for their boss. “Compared to other people I worked for, he treated the team like second-class citizens,” says former guard Terry Steans. For example, guards were not allowed to touch Fayed’s children, who, they say, delighted in taunting them. Bill Dunt says various children “spit at the guards,” hit them with sticks, and called them “donkeys.” Steans adds, “Because Fayed’s English is not sound, everything is the f-word. And when he goes, he’s got a very short fuse, and it doesn’t take much to set him off.”

Fayed’s building at 60 Park Lane contains 50 apartments, which he uses for his family, staff, and guests. He also owns the adjoining No.55, consisting of apartments for rent, as well as a building around the corner on South Street. All three buildings are connected to the Dorchester Hotel-which Fayed purchased for the Sultan of Brunei-by a series of secret passageways and an elaborate alarm system. One man who was being interviewed for a job at Park Lane was ushered into a waiting room and heard the click of a lock as the secretary left the room and closed the door. After about 20 minutes, the man looked up to see some bookcases which he had thought were built into the wall suddenly swing open and Fayed walk through them, hand outstretched.

Guards say that bugging equipment is kept in a basement room on the corner of South Street and Park Lane. In addition, says Dunt, “everybody who calls Fayed at 60 Park Lane is recorded, and all telephone calls in and out of the building are logged on a computer.” Harrods’ management offices are regularly swept for bugs and wiretaps. Another former guard, Russ Conway, told me that he personally bugged meetings at Harrods. Employees’ phones there were also tapped. A former Harrods executive, newly hired, watched a guard come into his office every afternoon, open a panel in the wall, and take out what looked like a videotape and replace it with another one. Curious, he discovered a tiny video camera trained on his desk.

In 1990, Christoph Bettermann became Fayed’s number two, the deputy chairman of Harrods. He had worked for Fayed in Dubai since 1984. In April 1991, Bettermann was approached by an American headhunter to work in the Arab emirate of Sharjah, and almost immediately, he says, Fayed told him, “I hear you are leaving me.” In June, says Bettermann, “he showed me a written transcript of a phone conversation between the headhunter and me. He accused me of breaking our trust by talking to these people. I told him, ‘If you don’t trust me, I resign. I cannot trust you if you bugged my phone.’ ” Bettermann quit Harrods and took an oil-company job in Sharjah.

Fayed promptly wrote the ruler of Sharjah, accusing Bettermann of stealing large sums of money. In a meeting with John Macnamara, an ex-Scotland Yard detective who is Fayed’s security director, Bettermann asked if he was being taped, and Macnamara said no. A tape of that meeting later surfaced. Bettermann was cleared by three courts in which Fayed had pressed charges, but Bettermann’s defense cost him $160.000. “Fayed has every law firm in London sewed up. It was intimidating,” Bettermann says. “Fayed charms you at first. Once you do not turn out the way he wants, you’re the bad guy, and he tries to get rid of you, sometimes in appalling ways.”

Bettermann’s wife, Francesca, who was Harrods’ legal counsel, resigned when her husband did. “The most common thing at Harrods was unfair dismissal,” she says. “We had a huge amount.” Last year Harrods was facing 32 such cases, compared with 2 at Selfridge’s department store, which has a similar number of employees. “The law says you can’t fire people without cause. Mohamed says, ‘I can, as long as I pay for it.’ ” Francesca Bettermann adds, “He settles them all. He has never gotten into the witness-box. I think he’d be very frightened to go to court.” Yet even when his lawyers told him that he couldn’t win, she claims, he’d say, “Sue. Sue anyway.”

When Francesca Bettermann was hired, she had to take an H.I.V. test-women working close to the chairman had to undergo full internal exams and be grilled on their entire gynaecological histories-and her handwriting was analyzed. (In 1994, three former Harrods employees claimed that they were given H.I.V. tests although they had specifically withheld permission to be screened. Michael Cole says it was the doctor’s fault. The doctor had blamed the medical lab.) Fayed has a strong phobia about germs. He does not eat out except on rare occasions, and eats only what his personal cook prepares for him. Each plate he eats from must be boiled and rimmed with a cut lime to disinfect it. When he helicopters from his country house to London, he wears a gas mask so that he won’t inhale fumes.

Whenever Fayed suffers a spate of bad publicity, the press seems to be flooded with stories and pictures of him helping needy children. In fiscal 1994, Fayed had House of Fraser donate £800.000 ($1.2 million) to charity. Yet Fayed’s fear of germs is such, say ex-employees, that he can, barely stand to touch the children who get him so much positive press. He does not allow his own children to attend the annual Harrods Christmas party, they say, for fear of contamination, and he keeps Wet-wipes in his pockets so that after shaking every little hand he can wipe his own.

He does not abide smoking. Revlon chairman Ronald Perelman showed up to meet Fayed in his office several years ago with his trademark cigar stuck between his teeth. According to an observer, before Fayed shook hands or said a word to Perelman, he yanked the cigar out of his mouth and threw it against the wall.

The boss’s strong likes and dislikes quickly become apparent to those who work closely with him. “He likes a pretty face. He wouldn’t hire someone who was ugly. He liked them light-skinned, well educated, English, and young,” says Francesca Bettermann. “I remember there was something on the application form that said, ‘Your color, race…’ I said, “You’re not allowed to put that on the form,’ and he said, “Well, make sure they put proper photos in, then.’ ” Last year, Harrods settled five racial-discrimination cases against the company, and, according to union officials, between June and September of 1994, 23 of the 28 people fired were blacks, who had held mostly menial jobs. Meanwhile, The Guardian reported that a Harrods spokesman had said, “Mohamed Al Fayed is very aware of the evils of racism. He hates racial discrimination in all its forms, and he would not entertain anybody working for him who might decide they should start acting this way.”

Fayed, ex-employees told me, changes his mind constantly, without warning. People who had worked for 20 years or more at Harrods were escorted off the premises in five minutes after having been told they were “redundant.” Police were sometimes summoned for minor infractions, and officers hauled one executive off a plane at Heathrow. Shortly before Michael Ellis-Jones, ex-managing director of Harrods, left, he told staffers, “You can’t run this place like a harem. The men aren’t eunuchs, and the women aren’t serfs.”

According to former employees, Fayed regularly walked the store on the lookout for young, attractive women to work in his office. Some were asked to go to Paris with him. Good-looking women were given gifts and cash bonuses almost before they understood that they were being compromised. “Come to Papa,” he would say. “Give Papa a hug.” Those who rebuffed him would often be subjected to crude, humiliating comments about their appearance or dress. A dozen ex-employees I spoke with said that Fayed would chase secretaries around the office and sometimes try to stuff money down women’s blouses. A succession of women were offered the use of a free apartment on Park lane or a luxury car.

Former Harrods workers can tell Fayed stories late into the night. He would brandish a two-foot plastic penis at male visitors and ask, “How’s your cock?” He bought several of Liberace’s pianos and ordered a painting of Harrods on Waikiki Beach, by actor Tony Curtis, to be reproduced for sale. Then there was Salah

Fayed, the peculiar third brother, codenamed by the security guards “the fruit bat” because he came out only at night. Salah, who lives in Egypt, has not applied for British citizenship; indeed, he is no longer even a director of Harrods. Salah once bought two 18-inch miniature horses, one for one of Mohamed’s daughters and one for himself, which he would walk on a leash down Park Lane. When Mohamed found out, he ordered that Salah’s horse be removed.

The atmosphere in Harrods was terrifying to some, and it fostered political backbiting. Why, if so many people felt they were so badly treated, did they wait to be fired? Many of them would say that in a country where unemployment runs high the Harrods name carried the day, and Fayed’s money bred their dependence. “He takes you on and pays you a relatively good wage,” says former security man Bill Dunt. “You begin to live according to your wage, and when it comes to the thought you might lose it, they’ve got you.”

Fayed’s acquisition of Harrods coincided with a wide-open laissez-faire period in Britain in the mid-80s, when, under Margaret Thatcher’s pro-business government, entrepreneurship was exalted as never before and strictures in the City were loosening. The casinos were awash with spectacularly rich Arabs, the brash Americans at Salomon Brothers and Goldman, Sachs were coming on strong, and after the Big Bang-the deregulation of Britain’s financial markets in 1986-staid British investment banks and law firms did not want to be left behind.

There’s an old Arab saying, “Find out what a man wants and give it to him.” Mohamed Al Fayed was one of those who provided visiting Middle Eastern potentates with whatever they desired. From his early boyhood in the Gomrok slum in Alexandria-not far from the exclusive Yacht Club-he had tracked the rich. After a flamboyant and checkered early career, he had ended up as a commissions agent and middleman for one of the world’s wealthiest men, Mahdi AJ Tajir-the right hand of Sheikh Rashid of Dubai. But they had a falling-out. “He was a bagman. Your role as a bagman is exactly that. You owe 90 percent of the money to those whose bag you’re carrying,” says financial journalist Michael Gillard, who professionally has been both a friend and a foe of Fayed’s. “If you do enough deals and the deals are big enough, you can make tens, hundreds of millions of dollars.” Fayed also arranged parties. “If sheikhs were coming, he’d lay on a string of girls for parties,” says Gillard.

In 1979, Fayed had renewed an old acquaintance with Tiny Rowland, and he began to feed business reporters from Rowland’s Observer leads for stories on bribes and corruption among his enemies in the Gulf. He and Rowland used to breakfast together, and Terry Robinson, Lonrho’s former director responsible for House of Fraser, remembers that Fayed always seemed obsessed with sex. “He’d thrust on Tiny all these sex toys. He’d come back from these breakfasts laden with devices.” Rowland and Fayed had met in the early 70s, when Lonrho bought Fayed’s shares in the British construction company Costain and Fayed went on the Lonrho board. The relationship quickly frayed. “I ran away from all the crooked dealing, all the arms dealing and bribes,” Fayed claimed. When I informed Rowland the next day that Fayed had said that he ran a “dirty company,” he was taken aback. “Our chairman was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill, Lord Duncan Sandys. If Fayed refers to us as a ‘dirty company,’ he should have refused to join a company chaired by Duncan Sandys.”

Born Roland Walter Fuhrhop in a German internment camp in India during World War 1, Tiny, by 1979, had made a fortune in Africa and held a 29.9 percent stake in the House of Fraser department stores. Lonrho frequently expressed interest in buying all of it, but had been ruled against by the British Monopolies and Mergers Commission, which regarded Lonrho’s bid as not in the public interest. When Fayed, whom Rowland nicknamed Tootsie, offered to buy Lonrho’s shares in House of Fraser, Rowland believed he had found a perfect vehicle with whom to park the stock until the political climate changed and he could find a way to acquire the whole company himself.

Clashing with the government was nothing new for Rowland. In 1973, after a power struggle at Lonrho, the D.T.I. had investigated him and produced a blistering report. Prime Minister Edward Heath had called Rowland “an unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.” (Rowland rejoined, “Of course, being called the acceptable face of capitalism would be equally insulting.”) Like Fayed, he was a self -invented outsider who sought to be more English than the English. Elegant, amoral, charismatic, and six feet two, Rowland was considered by many Africans to be a latter-day Cecil Rhodes. Others condemned him for bringing to that continent a way of doing business that depended on pay-outs and the granting of favors. In Britain, where he was educated as well as detained and jailed during World War II as a German sympathizer, he was adored by Lonrho shareholders but scorned by the Establishment.

Rowland had a vast network of contacts and close personal relationships with African leaders. He knew things before anyone else. “Rowland could never be prosecuted in this country,” Michael Cole claims. “Within a half-hour he could say enough to destroy the British Commonwealth. He’s the man who knows too much.” I asked Cole if Rowland’s information was correct. “Yes. He knows everything.” (Ironically, Cole denies most of what Rowland alleges about Fayed.) But for all his savvy, Rowland underestimated the wily Egyptian.

The purchase of Harrods came during a propitious moment of Fayed’s life, when he had ingratiated himself with the richest man on earth, His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’Izzaddin Waddaulah, the Sultan of Brunei. The credulous sultan was irresistible to those who trafficked in the world’s most expensive luxury goods and services, and wheeler-dealers from far and wide exhausted themselves trying to juggle their wares and prostrate themselves before him. Between the summer of 1984 and the spring of 1985, Fayed managed to elbow the competition aside.

Fayed told me that he had known the sultan as a little boy and his father before him. He also said they got to know each other over discussions about building a trade center in Brunei. Tiny Rowland gave the D.T.I. another explanation. He said Fayed had told him that he negotiated an introduction to the sultan for $500,000 plus a piece of the action of any resulting business with a hustling, globe-trotting Indian holy man, Shri Chandra Swamiji Maharaj, known as the Swami.

The Swami, a heavy-set former scrap-metal dealer once detained in jail on fraud charges, is today a power broker in New Delhi with close ties to Indian Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao, and he has numbered Imelda Marcos and Elizabeth Taylor among his followers. He was especially sought-after once he became “spiritual adviser” to the sultan’s second wife, Mariam, a former air hostess, in the course of predicting (incorrectly) that she would give birth to a son.

Through the late Washington lawyer Steven Martindale, the Swami met Fayed’s old enemy Adnan Khashoggi. Fayed had once been married to one of Khashoggi’s sisters, and he had fallen out with the family. Martindale, with financial help from Rowland, later wrote a truth-is-stranger-than -fiction book about his experiences with the two men and their connections with Fayed. Called By Hook or by Crook, the book was never distributed. Fayed issued a libel writ on the press release announcing the book and told the English publisher that if he ever wanted to sell another book in Harrods-one of the largest book outlets in Britain-he would not publish Martindale. When I asked Fayed about his association with the Swami, he laughed and said that they had met only once.

Beginning in the summer of 1984, Fayed received several powers of attorney and written authorizations from the sultan to carry out certain tasks for him. These powers of attorney gave him legal access to large sums of the sultan’s cash. Two mandates to act on the sultan’s behalf were given on August 20, 1984, and were to be used to cancel two previous contracts for the construction of a luxury yacht. Another, dispensed three days later, and naming Fayed “our personal and official Financial Advisor,” was issued to retrieve nearly $100 million the sultan had advanced to a Swiss businessman named Carl Hirschmann. Hirschmann was to have customized for the sultan a special stretch 747 jet with several bedrooms and stalls so that the sultan could fly non-stop from Brunei to London with his polo ponies. They were trying to find out what to do about the horses’ urine when Fayed reportedly persuaded the sultan to dump Hirschmann. Hirschmann’s son was detained in Brunei until $86 million of the sultan’s money was returned to a bank account Fayed would have control over. In addition, according to the D.T.I. report, another $200 million of the sultan’s on deposit for the design of the yacht was transferred away from the marine designer’s control by Fayed “once he had himself been granted appropriate authority by the Sultan.”

In June 1984, say the inspectors, the Fayed brothers had $69 million on deposit, “whatever its original source,” in the Royal Bank of Scotland. But in the next two months, Mohamed was also busy incorporating two holding companies as receptacles for the brothers’ assets in Liechtenstein, and traveling between Brunei and London acquiring the powers of attorney from the sultan. During that same period, according to the D.T.I. report, the three Fayed brothers’ bank, the Royal Bank of Scotland, received a sudden transfer of hundreds of millions of dollars from Switzerland into the Fayeds’ accounts. Fayed has never really explained where this money came from; the bank assumed it belonged to the sultan. However, Fayed told the bank that his portfolio was separate from the sultan’s. “It may be no more than coincidence that this vast increase in disposable wealth followed quickly on the admission of Mohamed to the sultan’s confidence,” wrote the inspectors. “It is, however, a very powerful coincidence.”

By November, Fayed had struck a deal with Rowland to buy his House of Fraser shares for £138 million ($171 million). Rowland incorrectly assumed that the shares would be safely parked if he let Fayed have them, because he was sure that Tootsie didn’t have the capital to acquire more. “I sold because I wanted him to keep the stock. I’ve made many mistakes in my life, but the worst was I trusted him!”

Almost immediately, Fayed demanded that Rowland leave the House of Fraser board, and went behind Rowland’s back to court the House of Fraser chairman, Professor Roland Smith, who received a handsome retroactive bonus from Fayed once he obtained ownership.

Rowland also wrongly believed that if Fayed made a bid to buy a controlling interest in House of Fraser, it would never get past government investigation. “We were in the right place at the right time,” says Michael Cole. “They’d let anybody buy it who wasn’t Rowland.”

Next, the little-known Fayeds and their new advisers had to convince the government and the public that they controlled enough assets to be able to hand over $700 million unencumbered. It required them to invent a history of old money; overnight they became “fabulous pharaohs.” The Fayeds were represented by the investment bankers Kleinwort Benson and the law offices of Herbert Smith, two old-line British firms which basically accepted at face value what the Fayeds told them. “Remember,” said Kleinwort’s John MacArthur, who handled the deal for the Fayeds, “Kohlberg, Kravis Roberts was buying out RJR Nabisco on bus tickets. It was go-go time.” As the D.T.I. report put it, “The lies which the Fayeds were telling about themselves and their resources were given a credibility they would not have otherwise attained when they were repeated by their very reputable advisers.”

The Fayeds’ bankers submitted a now discredited one-and-a-half –page summary of their assets, which the government accepted. On November 2, Kleinwort issued a press release about its new clients: the Fayeds were an “old established Egyptian family who for more than 100 years were ship owners, land owners and industrialists in Egypt.” To this day, the brothers are said to be “raised by British nannies, educated in British schools and unabashed admirers of British history, traditions and ethics.” When Nasser came to power, they fled. With a couple of notable exceptions, the press swallowed the story whole.

“Statements about the sources of their great wealth and about the scale of their businesses formed part of their central story,” wrote the D.T.I. inspectors later. “If people had known, for instance, that they only owned one luxury hotel; that their interests in oil exploration consortia were of no current value; that their banking interests consisted of less than 5 percent of the issued share capital of a bank and were worth less than $10 million; that they had no current interests in construction projects: that far from being ‘leading shipowners in the liner trade’ they only owned two roll-on roll-off 1600 ton cargo ferries; if all these facts had been known people would have been less disposed to believe that the Fayeds really owned the money they were using to buy HOF.”

Fayed entertained the wowed House of Fraser board at the opulent 60 Park Lane and flew the Harrods manager over to the Ritz. American public relations advisers were hired-never knowing whether they were being paid by the sultan or Fayed-to broadcast the sultan’s good works. Sir Gordon Reece, one of Margaret Thatcher’s kitchen cabinet and her TV-image adviser, who was also advising Fayed, was provided with a Park Lane apartment.

In January 1985, Fayed received another power of attorney to quietly purchase the Dorchester Hotel for the sultan. On January 29, Fayed accompanied the sultan to 10 Downing Street to visit Margaret Thatcher. The pound at that time was in drastic decline, threatening the economy, and the sultan, who had moved £5 billion ($5.6 billion) of assets out of sterling, kindly did Britain a grand favor. He moved it back in. Fayed has taken credit for the assist and also for persuading the sultan to give British defense industries a half –billion pounds ($560 million) in contracts.

On March 4, 1985, the Fayeds announced a formal cash offer for House of Fraser of £615 million ($689 million), which Kleinwort claimed was untethered by any borrowings. The financing of the Fayeds’ bid has been the source of intense scrutiny, and while no one, including Fayed, has supplied a comprehensive account, some numbers have emerged. According to the D.T.I. report, by October 1984 the Fayeds had at their disposal at least $600 million in the Royal Bank of Scotland and in a Swiss bank. “We were not told the source of any of these funds or given a credible story as to how and where they were obtained,” said the inspectors. Tiny Rowland claimed that the architect behind the sultan’s 1,788-room palace, Enrique Zobel, had said that Fayed controlled $1.2 billion in yet another joint account with His Royal Highness. Whatever the amount, the huge pile of cash the Fayeds claimed as their own was apparently used as collateral in order to guarantee a loan of more than £400 million ($480 million) to buy House of Fraser.

“If you have a company with tremendous assets like Harrods,” Fayed told me, “you have no problem. You don’t need to use cash.” That first loan, drawn on a Swiss bank, was then quickly replaced with another loan. secured by House of Fraser shares. Thus, within a short period of time, it seems, the Fayeds owned House of Fraser and didn’t have any of their own money in it.

“Nobody’s been able to find out whose money is behind the purchase, because of secrecy laws of Swiss banking codes,” asserts Terry Robinson, who spent nearly two months researching the Fayeds’ accounts for Lonrho. “The D.T.I. inspectors tried, and sought British-government assistance. The Swiss will cooperate, but it has to be on a government-to-government basis. The British government refused the inspectors’ request. That, to me, is the fishy side of things.” The inspectors were thus denied definitive proof. Nonetheless, they said they were left to conclude “that this was somebody else’s money,” and, further, that “the conclusion that the money was derived from [Fayed’s] association with the Sultan looks not only possible but probable.”

Tiny Rowland wrote Trade Minister Norman Tebbit a seven-plus-page letter repudiating the Fayeds’ story, according to Tom Bower, who wrote an unauthorized biography of Rowland. Rowland also enlisted the former director of the Egyptian secret police and Nasser’s son-in-law, Ashraf Marwan, to aid him in exposing the Fayeds-who had previously enlisted Marwan to help them buy Rowland’s House of Fraser shares.

A full-scale press battle began. Brian Basham, a slick P.R. adviser whom Kleinwort brought in for the Fayeds, was spinning pro-Fayed pieces while Tiny Rowland sought to influence his newspaper, The Observer. On the weekend of March 9 and 10, The Observer published an article using some of Marwan’s information. That Sunday night on national television, John MacArthur of Kleinwort blithely reiterated that the Fayeds were worth “several billion dollars” despite the fact that he also admitted, “I have got no statement of their consolidated financial position.” The next morning, March 11, the Fayeds bought more than 50 percent of House of Fraser.

Fayed issued what was later referred to in the D.T.I. report as a “gagging” writ, a libel suit against The Observer for its Sunday story. Whenever any newspaper deviated from the Fayed version, similar writs were routinely threatened or issued. All critical reporting outside The Observer virtually stopped.

On March 14, 1985, the government issued a press release announcing that it would not refer the Fayeds’ bid to the Monopolies and Mergers Commission. The bloody battle was over. The Fayeds owned Harrods. But the war had just begun.

Between 1985 and 1993, Tiny Rowland relentlessly pursued Mohamed Al Fayed. “Anyone who fell out with Mohamed knew where to go,” says journalist Michael Gillard. Rowland’s suspicions were further aroused when, just a few hours before the announcement on March 14, 1985, Fayed showed up at 10 Downing Street for a reception in honor of President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, whom he had never met. According to Bower’s biography, the invitation had been arranged by Mubarak’s and Mrs. Thatcher’s mutual adviser, Gordon Reece, who, several people told me, kept his free Park Lane apartment courtesy of Fayed from the spring of 1985 until the summer of 1994. (Reece denies both claims.) Since then, according to former Harrods employees, the Egyptian president’s family has enjoyed Fayed’s hospitality at Harrods, and while Mubarak’s son was living in London, his apartment was decorated by Fayed.

After the controversy generated by the House of Fraser affair, business relations between Fayed and the sultan suddenly ceased. On April 25, 1985, the sultan and Fayed terminated, by mutual agreement, all powers of attorney given to Fayed since 1984. Publicly the sultan has always denied that his money was used. “What the sultan says… is that if any of his money was used in the purchase of the House of Fraser it was without his knowledge and consent,” explained the sultan’s public-relations adviser, Lord Chalfont, in 1989. Chalfont also said that the sultan, “has decided to retain more professional advisers and has ceased all commercial contacts with Mohamed Al Fayed.”

In a 1988 article in Forbes by Pranay Gupte, it was first reported that the Swami and the sultan had met in Singapore in 1985 to discuss ways of getting back part of the $900 million the sultan had “entrusted” to Fayed. Acting on behalf of the sultan, the Swami persuaded Fayed to meet with him on June 6 and 7, 1985, in a rented apartment at 1 Carlos Place in Mayfair, and the meetings were secretly tape-recorded. On these infamous “Carlos Place tapes”-partly in Hindi, partly in broken English, but mostly gibberish-which the D.T.I. subsequently had authenticated by an audio lab, Fayed brags to the Swami about his influence with both Mrs. Thatcher and the sultan. “I have power of attorney… I can have $10 billion if I want.” Gupte, who speaks Hindi, and Michael Gillard, both of whom have interviewed Fayed, told me the voice on the tapes is unmistakably Fayed’s. Fayed once swore in an affidavit – and still avers today – that the tapes are not authentic.

Rowland, however, believed the tapes were just the smoking gun he had been looking for. Once he found out about them from Adnan Khashoggi, he flew to New York, where he met the Swami in Khashoggi’s 45th-floor duplex, and then to Canada, where the tapes were stashed, to listen to them. Later, a delegation from Lonrho met the Swami aboard Khashoggi’s yacht in Antibes and paid $2 million for the tapes. (Rowland also paid $3 million for a document purporting that Mark Thatcher, the son of the prime minister, and Fayed had traveled to Brunei together, which was later proved false.) The transcript of the tapes yielded Rowland a 185-page peccadillo-laden biography of Fayed, printed privately and sent “to anybody who was qualified”-80,000 of them. It was called A Hero from Zero, which is how the Swami described Fayed at Carlos Place, and it caused a sensation.

When I visited Rowland at his posh town house on Chester Square last November, the silver-haired titan casually picked up a phone and promptly got through to “His Holiness,” the Swami, at his ashram in India. His Holiness would be interviewed only in person. Then Rowland made another call and handed me the phone. I was talking to Adnan Khashoggi-on the record.

“The tapes are authentic. The Swami taped him on the sultan’s orders,” Khashoggi said. “In my mind he definitely, officially bought Harrods with the sultan’s money. I saw the agreement. He gave the sultan £300 million [$390 million] back.” Did the sultan show you the agreement? I asked. “No. The sultan showed it to the Swami, and the Swami showed it to me.”

Khashoggi and Fayed have a long history. They met in the early 50s, when Fayed was married to Samira Khashoggi, whom he had met on the beach in Alexandria. She gave birth to a son, Dodi. Today, Dodi Fayed, who got a producer’s credit on Chariots of Fire, continues to function in the film business. Khashoggi claims that at the time of their meeting Fayed was a Singer sewing-machine salesman who had previously sold Coca-Cola. Khashoggi gave him a job coordinating furniture deliveries for a company that he owned. “He started making side deals to put fees in his hands,” Khashoggi claims. Fayed says that Khashoggi worked for him, and that he couldn’t take Khashoggi’s stealing and gambling away his money. “It was such a dirty family.”

In fact, Khashoggi’s father was the doctor of the late Saudi Arabian king Abdul-Aziz. According to Fayed and Michael Cole, however, Khashoggi’s father was merely “a nurse orderly” who injected the old king so that he could perform sexually with the virgins who were brought to him nightly. When I repeated this to Khashoggi, he said, “It makes the story more fairytale. My father is a surgeon, who studied with Madame Curie.” Khashoggi added, “Mohamed always had the image of lying and making up stories – “It’s a sickness.”

In 1987 the Conservatives were facing a general election, and numerous business scandals had fueled criticism that their regulation was too lax. Rowland was still relentlessly pounding the government about Fayed, and, more important, The Observer had begun publishing stories critical of the business dealings of Mark Thatcher, the adored son of, and frequent embarrassment to, the prime minister. The government also learned from the D.T.I. report that Kleinwort Benson had based its confidence in the Fayeds’ assets on a single telex from a Swiss bank and on the sultan’s denial that he was involved. On April 9, 1987, the Department of Trade and Industry appointed inspectors to look into the acquisition of Harrods, if only to keep Rowland and The Observer quiet. To this day, the British government has chosen never to explain fully why, although the D.T.I. report was completed in July 1988, it was not officially released until March 1990, and why, since it was full of damaging findings, it was never acted upon. To most Americans, this would indicate a clear cover-up. The report might never have been published at all if Rowland hadn’t gotten a hold of it and printed its findings in March 1989, in an extraordinary mid-week edition of The Observer, which usually publishes only on Sundays. Fayed and the government obtained an injunction which forced the paper off the newsstands within a few hours.

Only recently has it become possible to piece together how desperately Fayed was trying to curry favor with the Conservative Party while he was under investigation. Between 1985 and 1987, he not only gave the Tories £250,000 ($367,000) for the 1987 election but also met dozens of times with Tim Smith and Neil Hamilton – the two ministers whose resignations he would later force – sometimes alone and sometimes with lobbyist Ian Greer, whose firm acted as Fayed’s go-between. (Hamilton, who stayed free at the Ritz, admits to attending meetings but denies receiving payment. He and Greer sued, but their action was recently struck down.) The meetings stopped six months after the D.T.I. report was published in The Observer. Last month, Fayed was called to tell what he knows in an inquiry involving Jonathan Aitken, another minister implicated in the scandal over free stays at the Ritz.

During the late 80s, while Rowland continued to flood the Establishment with reports detailing the Fayeds’ background, Mohamed, according to two ex-security guards, kept wooing high-ranking officials in the Thatcher government. He played host in Surrey, for example, to then home secretary Douglas Hurd, who resigned this June as Major’s foreign secretary. To counter Rowland, Fayed set up his own digging-for-dirt department, headed by lawyer Royston Webb and private investigator Richard New. They produced a scathing, Nazi-baiting propaganda report on Tiny: Faircop Fuhrhop. Lord McAlpine likened the struggle to watching afternoon wrestling on TV. “Nobody quite cares who wins, but it’s fun to watch for half an hour.” It wasn’t, he says, as if anything important were at stake. Harrods, after all, was just a shop.

Since the scandal Fayed has continued to invite politicians of all parties up to his offices, where he plies them with drink and bags full of Harrods goodies. “He has loads of politicians up there, and they all get the red-carpet treatment,” says former security guard Russ Conway, who says he was dismissed on a whim in March. “There’s liquor all over the place. Half of them can’t walk because they’re stone drunk. Then you’re dispatched to go down and bring up big teddy bears in bags, and if they hadn’t got a car, you’d drive ’em to [the] Commons.”

Fayed and Rowland both employ former Scotland Yard detective chief superintendents as security heads, men whose close ties to the police are ongoing and of enormous help to their bosses. “They were both hired for their contacts, and still to this day they use them,” says former security guard Bill Dunt. “They still have access to the police.”

In 1990, shortly before the D.T.I. report was officially released, 1,000 copies of the report bound in Moroccan leather and meant to be sent to everyone from “the Queen on down” turned up in Bangkok in the possession of a German arms dealer named Herman Moll. He claimed he had been hired by Khashoggi lawyer Sam Evans, who had helped Rowland write A Hero from Zero. (Rowland claimed that the report had landed on his desk in a brown envelope.) Moll called Fayed’s security chief, John Macnamara, asking for more than £1 million ($1.8 million) for the report. Macnamara flew to Bangkok and managed to grab a copy away from Moll in a hotel bar.

Finally, in March 1990, five years after the Fayeds’ purchase of House of Fraser, Nicholas Ridley, the then secretary of state for trade and industry-the fifth since the fight had begun-released the D.T.I. report, because, he said, the Department of Public Prosecutions had decided there were no grounds to prosecute. “Only God can take House of Fraser from me,” crowed Fayed.

“If I had to do it all over again,” says Fayed, “I could. I could sleep in Hyde Park. All I would need was a piece of bread and some cheese.”

“Among all the boys, we called him Fayed the Liar,” says Ibrahim El Araby Abou Hammed, a former classmate who says he has known Fayed since they were seven in the Gomrok. “All the time he was dreaming to be rich. He wanted to dress and walk around with the rich people. He is one week older than I am,” says El Araby, who was born in 1929. Fayed claims he was born in 1933. The D.T.I. report flatly says he lied. But such talk is dangerous. El Araby, once the editor of Alexandria Magazine, was beaten while helping a British TV crew investigate the Fayeds’ origins, and his magazine had to close. Channel 3 broadcast that three eyewitnesses had identified Salah Fayed as the man who attacked El Araby. House or Fraser categorically denied that Salah had had anything to do with the incident.

Perhaps Fayed’s greatest caper before Harrods was the brief time he spent in Haiti. “He introduced himself as Sheikh Mohamed Fayed,” Luckner Cambronne, Papa Doc Duvalier’s former right-hand man, says today. Fayed arrived in Haiti in late 1964, when Papa Doc, the brutal dictator, was increasingly isolated. Fayed told people that he could bring Middle Eastern riches to the wretchedly poor island if they would allow him the concessions to build an oil refinery and develop the wharf at Port-au-Prince. In short order a contract with an American firm was canceled, and Fayed was being driven around in a limousine with Tonton Macoute bodyguards and given a diplomatic passport. According to Raymond Joseph, editor of the Haiti Observateur newspaper in New York and one of the organizers of the opposition to Papa Doc at the time, Fayed became engaged to one of Papa Doc’s daughters, and whenever he made a trip to Miami, he’d send flowers to Madame Duvalier. “It was like giving Indians trinkets, and you steal the whole thing.”

Although Fayed claimed that he had invested $4 million in Haiti and that the government owed him money, the D.T.I. inspectors found his signature on an account for the harbor authority in October 1964, when the account held just over $160,000. By the end of the year, both he and $150,000 were gone. “We have no doubt at all that Mohamed Fayed perpetrated a substantial deceit on the government and people of Haiti in 1964.”

After Haiti, Fayed landed in London and moved into a flat at 60 Park Lane, which he would later acquire. He began traveling frequently to Dubai, and today takes credit for building its harbor and trade center, though those claims are widely disputed in Dubai. Through commissions and his association with the Dubai billionaire Mahdi Al Tajir, Mohamed became rich, and two British construction firms, Sunleys and Costain, give him credit for helping them gain hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth or business in Dubai. This year, however, in arbitration with the ruling Makhoum family, he lost the management contract for the Dubai trade center, and he can no longer have a shipping business there. For failing to comply with government regulations, he has effectively been banned from Dubai.

In the 70s, Fayed met his Finnish wile, Heini. According to numerous former employees, the union appears volatile. The couple is rarely seen together in public.

In 1979 the brothers bought the Ritz hotel in Paris. Their accumulated losses on the opulent establishment have been enormous. The hotel’s debts at the end of 1993 were 678 million francs ($120 million), compared with total revenues for 1993 of 243 million francs ($42 million). “The only thing pharaonic about the Fayeds is the size of their debt,” says Michael Gillard. The Fayeds are very highly leveraged, but the brothers explain away their vast borrowings as a tax advantage: under British law, interest on debt can offset taxes on profits.

According to figures obtained from Companies House, the official British register of corporations, between fiscal 1990 and 1994. House of Fraser Holdings paid an astonishing £458.9 million ($785.6 million) in interest to the banks-hardly the business procedure to be expected of entrepreneurs with billions at their disposal.

By the spring of 1993, the Fayed-controlled House of Fraser had spent £616.3 million ($925 million) of a £668.2 million ($1 billion) credit line, and the banks wanted their money back. In what appeared to be a quick bid to raise cash, House of Fraser took a whopping £68 million ($105 million) loss on its sale of 10.37 percent of Sears, the British retailing company, to raise £156 million ($240 million) in April 1993. The Fayeds were also strapped by numerous Lonrho lawsuits challenging their ownership. Imagine the surprise, then, when in October 1993, Tiny Rowland decided to end the feud.

Absolutely no one could have anticipated it. The news was so startling to those in the trenches who had slung the mud and to the attorneys who had been putting on the writs for 9 years that a 41-year-old lawyer, whose “whole career had been made on keeping track of all the suits for Lonrho-suddenly dropped dead of heart failure. Dieter Bock, a German businessman whom Rowland had brought in to replace him someday, knew that calling the whole thing off was worth a great deal to Fayed, who in April 1994 happily floated the now steadily declining House of Fraser stock for £413 million ($612 million). Bock, impatient with the battle that had cost both sides about $50 million, wanted it to be over with. At the same time, he was getting on Rowland’s nerves, to the point where he was replacing Fayed as Tiny’s number-one enemy. “They were going to try to settle for £5 to £10 million [$7.6 to $15.3 million], but Tiny jumped in and pre-empted the settlement. It made the board furious,” says Terry Robinson. “But then Tiny had a bigger fight with Bock than with Mohamed.”

Bassam Abu Sharif, a Palestinian adviser to Yasser Arafat, played the go-between. “I told Tiny if the Arabs and the Israelis could make peace, so could he and Fayed.” The feud was ended amid lights, cameras, and a very public lowering of a large stuffed shark-which Fayed had dubbed Tiny-from the ceiling in Harrods’ Food Halls. Both men insist that no money changed hands, and Fayed takes great pleasure in remembering shark day. “[Tiny] say he’s sorry. Kiss my hand. He say, ‘I am crazy to do this to you.’ ”

I asked Fayed why Tiny had ended the feud. As usual, Michael Cole had the answer. “Two things: One, it cost him £40 million {$61 million]. And the second one, if he was going to pursue his case against Mohamed, he would have had to go into the witness-box. He would never have done it.”

“He’s a lovely man,” Fayed jokes when I ask him what he thinks of Tiny today. Then his real feelings come out. “He’s a criminal. He is the worst person this country has from Germany. He has-how do you call it? – Nazi background… He’s bullshit, and he’s a liar.”

Only two weeks earlier, Fayed had secretly taped Rowland at a lunch at Harrods, although he insists that Tiny knew he was in front of a camera. “I interview him like David Frost,” Fayed claims.

“Do you think I would have gone there for lunch to be video-taped? I was stunned,” Rowland tells me. Rowland’s comment to the press about the alleged taping was to ask whether the tape also revealed the part of their conversation in which Mohamed urged Tiny to accompany him to the Mayo Clinic, where Mohamed would undergo a penile transplant. “I love the man,” Rowland continues, “He’s a pathological liar – he can’t help it. He began sitting on the back of a truck carrying crates of Coca-Cola, and he only just started paying his taxes.” (Cole claims that Fayed has paid more than £200 million [$320 million] in taxes in the last decade.)

For whatever absurd reason, the Fates have bound these two larger-than-life megalomaniacs together. Within a few days last March, tabloid headlines proclaimed that Tiny Rowland had been kicked out of Lonrho altogether, and that Mohamed Al Fayed had been denied British citizenship. Now Rowland vows to derail his new enemy, Dieter Bock, and Fayed hopes he can bring John Major’s divided and struggling government to its knees. The two outsiders, who thrive on conflict and enmity, exchange condolences frequently.

No Comments