Original Publication: Newsweek, March 26, 1973

In a rare change of pace, Capitol Hill is currently witnessing some happy Congressional hearings. Testimony on behalf of a budget boost for the National Endowment for the Arts is not only getting a warm reception from Congress (including once-hostile conservatives), but the Nixon Administration is actually requesting Congress to double current Federal spending on the arts from $38 million in fiscal ’73 to $80 million in fiscal ’74. Though much of the public remains unaware of it, the Federal government, in a break with long tradition, has become a grand patron of the arts.

Today grants from the National Endowment fund everything from saving totem poles in Alaska to sending a ballet company to tour rural Kentucky. Under Endowment programs 2,000 school districts in all 50 states have brought in poets, filmmakers and painters to work directly with children. Cannonball Adderley reviews requests from budding jazz musicians, and Kurt Vonnegut Jr. reads manuscripts sent to the Endowment’s literature panel. Opera companies mount new productions, symphony orchestras give free concerts in the parks and black artists paint outdoor murals in the inner cities. Top-flight professionals sit on the various arts panels under the Endowment and make the actual decisions affecting grants. The National Council for the Arts, which sets basic policy, includes such members as Duke Ellington, dancer Edward Villella and novelist Eudora Welty. It all adds up to one of the government’s most ambitious and dynamic programs.

Savvy: Unlike Europe, where state and municipal patronage is commonplace, the U.S. has relied on private philanthropy instead of government subsidy of the arts. It wasn’t until 1965, when Lyndon Johnson signed a bill creating National Endowments for both the arts and humanities, that full-time government support officially began. Appropriations the first year amounted to only 2.5 million, but because of skillful lobbying by key members of Congress plus the savvy displayed by Nancy Hanks, the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, arts appropriations have doubled almost every year. “One of the reasons funds have increased,” says the Florida-born Miss Hanks, “is that as usual the public is ahead of the Federal government. People want the involvement of arts in their daily lives.”

There is no doubt that Miss Hanks’s own efforts have had a lot to do with the government’s increasing interest in the arts. Behind her soft Southern drawl and gracious manner lies the mind of a keen administration with a through knowledge of Federal bureaucracy. “Nancy Hanks has good political sense, far better than most people in the Administration,” says Indiana Congressman John Brademas, who chairs the House Select Subcommittee on the Arts. “I would say she rivals Sargent Shriver in her willingness to inform Congress.”

The daughter of a prominent Fort Worth, Texas, attorney, Miss Hanks gave no early indication of becoming one of the most powerful forces in American culture today. After graduating magna cum laude in political science from Duke University, she headed for Washington. “My first job was as a receptionist in the Office of Defense Mobilization,” she told NEWSWEEK’S Maureen Orth. “It was the smartest thing I ever did. I was forced to learn the total workings of the Federal government in terms of defense.” After doing a stint in the office of the President’s Advisory Committee on Government Organization and working as an assistant to Nelson Rockefeller, Miss Hanks coordinated a special Rockefeller Brothers Fund report on the performing arts in 1963.

When Roger Stevens, the Endowment’s first chairman, finished his term in 1969, President Nixon named Miss Hanks to take his place. It was a period of fiscal crisis in the arts: when she took over, she found many of the country’s most important cultural institutions in deep financial trouble. Private philanthropy, which still far outstrips Federal subsidy of the arts, was no longer enough to do the job.

“The first thing I realized,” says Miss Hanks, “was that there was no point in just talking to the country about the arts. Fortunately I’ve had enough experience go to in and talk to individual members of Congress. I told them what was going on in their own states, their own districts. Many of them didn’t even realize that the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, for example, serves a five-state region.” Before Congress voted to fund the last appropriations bill for the Endowment in 1970, Nancy Hanks and her deputy, Michael Straight, talked to 150 members of Congress. Their efforts paid off—a hundred previously negative votes switched in favor of the program.

So far the Endowment has managed to rise above politics; most artists seem to have lost their fear that Federal patronage means Federal control. But some Democratic members of Congress are worried that the current legislation, which earmarks $30 million for programs relating to the nation’s bicentennial in 1976, might be used by the Administration to help Republican candidates in a Presidential election year. “This is our first big test,” says Straight. “We’re putting no money in parades or things that are purely celebratory. We’ll only support things of lasting value.”

Ceiling: Of course the arts are still in trouble financially, and the Endowment has its shortcomings. W. McNeil Lowry, Ford Foundation vice president for the humanities and arts, worries that the Endowment is spreading itself too thin. Ford itself has given more than $250 million to the arts in the last sixteen years, far more than the government or any individual. “The normal Endowment ceiling to grants to the theater or opera is only $100,000 to $150,000 a year,” Lowry says. “When those companies want real money to live on they don’t get it from the Endowment.”

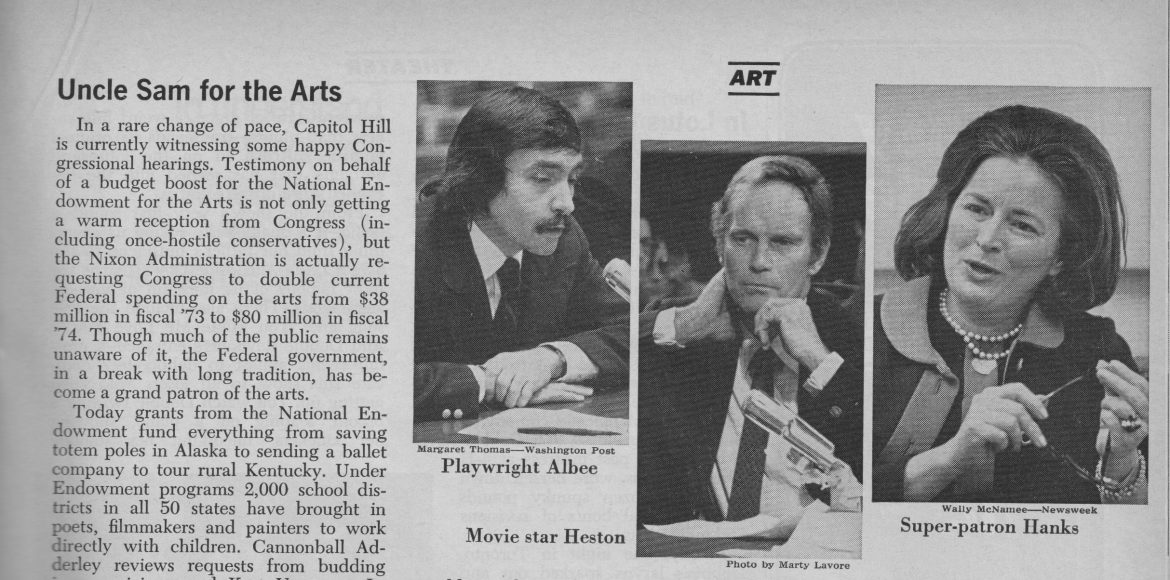

In the hearings last week, however, a parade of notables—such as movie star Charlton Heston, playwright Edward Albee, and movie critic Pauline Kael—praised the Endowment’s work and urged increased Federal support. In the meantime, Nancy Hanks is making sure the impact of the Endowment’s program is being felt where she thinks it is most important—among the people. An “Artrain” manned by working artists is whistle-stopping through the Rocky Mountain states, serving as catalyst for the only arts festivals many small towns have ever had. And recently, a rural town in Connecticut was treated to its first-ever square-dance caller—courtesy of the Endowment.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.