For Love and Money

Original Publication: California Magazine, December 20, 1970

They carry thousands of dollars around in paper bags and shoe boxes. Some of them make as much as $200,000 a year. They have Porsches, airstrips, Afghan hounds, live-in beautiful chicks, handmade clothes and some even buy stocks and bonds. Some of the fronts they use for safely investing their money include hip boutiques, leather crafts and candle making. Secret warehouses conceal their stash.

They supply the Bay Area people who turn on: How many people and how much marijuana, hashish, speed, smack, coke, acid and other unlawful drugs is anybody’s guess. Some say about a ton of marijuana is sold around the Bay each week. These are the dope lords of San Francisco. And they need lawyers.

Big time smugglers, small time dealers and the kid next door who gets arrested for a marijuana cigarette in his possession make up the clientele of some of the sharpest young criminal attorneys in San Francisco. They are a new breed of attorney for a new breed of criminal. They deal with dope and draft cases, negotiate contracts for rock bands and defend obscenity cases for underground comics. Their caseload runs the gamut of the youthful counter culture.

Long-haired freaks and uptight parents share waiting rooms in these lawyers’ Victorian mansions, lofts, and brick walled Jackson Square offices. Hip-chick secretaries type briefs, serve wine or make peanut butter sandwiches. The lawyers themselves may arrive on a motorcycle wearing cowboy boots.

The phones ring a lot. Someone is calling to say the narcs are inside his house. Somebody else, in jail, needs to know about bail. There’s a two o’clock courtroom appearance in Marin. An artist arrives, wanting to trade his posters for some legal services. A musician: “How about my bass guitar if you’ll take my case?” Should he? A Porsche, given as a fee a few months ago, turned out to be stolen. OK, so what’s another freebie?

Being, on the average, thirtyish competitive, highly individualistic, these lawyers grew up in the fifties and went to school in the early sixties before the Free Speech Movement. They are able to shift back and forth from one end of the generation gap to the other, soothe the parent, understand the frustration of the kid. Sometimes these lawyers wonder just where they’re at themselves.

Last year in California, more than 50,000 people were arrested for the possession or sale of drugs considered dangerous and unlawful by the California Health and Safety Code. Most of these arrests involved marijuana. In 1969, the State of California spent approximately 72 million dollars in police and court time prosecuting dope cases. The number of arrests in the first six months of 1970 has already reached 34,545. In terms of numbers alone, clearly, for a criminal attorney, dope is where the action is.

Although the dope lawyers’ predominant clients and income derive from the illegal use of marijuana, all are outspoken advocates of changing marijuana laws. Says Metzger, “The enforcement of marijuana laws is destroying some of our youth, making them distrust authority, putting kids in jail, destroying their futures, clogging the courts.

Dope crimes are known as victimless crimes. No victim is involved as in a robbery or a murder. Most dope cases revolve around two concepts: Search and seizure law (whether or not the prosecution evidence was legally obtained) and making deals.

Adamant that lawyers shouldn’t make deals is James R. White III, at forty-one the pioneer of the group who considers himself the “Martin Luther King of marijuana”:

“If everyone would stop being a coward, stand up and demand what the Constitution provides – a jury trial – the marijuana laws would be abolished in six months.”

Indeed, the courts cannot possibly bring every dope case to trial. There are too many cases and the courts are not nearly equipped to handle the load. As a result, defense attorneys make deals with district attorneys and judges.

Attorney Rommel Bondoc characterized dope law: “First, there is rarely a real trial on the facts. Most dope cases are tried on search and seizure laws which are based on technicalities and don’t get before juries that much. Second, the Supreme Court law on search and seizure is the most confused, arbitrary, nonsensical set of law in the whole world. It’s not coherent. And third, by a certain time, you can pretty well predict what the DA’s will go along with. There are too many cases to try. Besides, a lot of DA’s think some of the dope laws are wrong.

Hence, the deal. Attorney Brian Rohan recalls, “I had one kids who was busted with a pound of hash on him, a gun and four thousand cash in his pocket. He got probation because he had been an Eagle Scout.”

The charges against another lawyer’s clients – the smuggling of 400 kilos of marijuana across the border – were thrown out of court because the narcotics agents burst into their place without a search warrant.

Dope defendants expect their lawyers to be hip and smart, to intervene with the Establishment for them and often to explain away their ego trips.

One of the lawyers elaborates: “Lots of people who deal dope really can’t handle it. The whole life is devoid of traditional values. Dealers get ripped off. There’s lots of hassle. Though some dealers live with a detached, individualistic style, a large proportion of them gossip, backbite, and double-cross. While some are mystical and ascetic in their tastes, others are vain little peacocks. Most of them are more intolerant of straight people than straight people are of them. They reject society. They have no vehicles in the traditional sense to hang on to; they don’t want to join the army; they don’t want traditional business.

While some deal dope to support their friends, families and causes, others are just plain lazy. They jump on the bandwagon just so they can blame Mommy and Daddy. My criticism is the abdication of responsibility for personal failure.”

The reaction of a lot of parents is to disbelieve their children are mixed up with dope.

The other side of the coin is that many smugglers do not consider their acts illicit: these dealers really feel they have a mission to “turn on the world.” They only deal in the “finest,” the purest product.

Other dealers are hip capitalists, intent on amassing wealth in a totally unregulated market which fluctuates according to supply and demand. Still others may deal just long enough to get the money to start a communal “family” or a legitimate business.

There is a fraternity among dope dealers that makes them generous to one another. One night before Attorney Daniel Weinstein left for a trial in Greece, someone dropped a thousand dollars through his cat door with a note, “Help my brothers.”

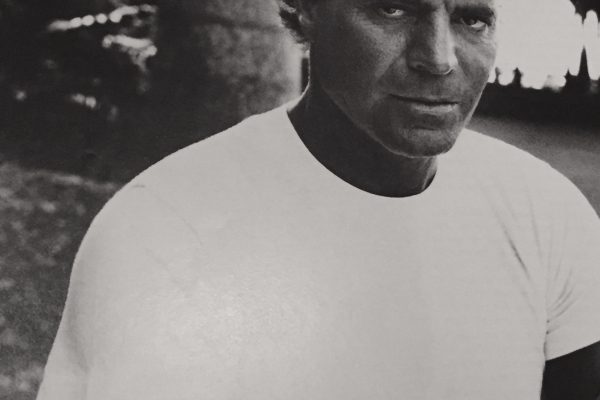

Brian Rohan, though he is probably one of the most successful dope lawyers, hasn’t worn a suit in a year, his usual attire being faded corduroys and a T shirt. He wears dark glasses at all times. “I can’t look people in the eye when I ask for all that money – I get it, and it’s insane.” When he wants to drive his battered four-year-old mustang convertible he climbs in the back since the front doors don’t open. It isn’t that Brian is a miser, he just doesn’t seem to care.

Restless, moving through life at triple speed, relishing new challenges, Brian now is leaving the dope scene and devote his entire time to rock music and movies. Earlier this year Esquire named him one of the “Heavy 100” people in rock and roll.

He and his partner, Michael Stepanian, were the first San Francisco lawyers to defend hippies in large numbers. Brian talks like the historian of hip.

“When I got ready to practice law I looked around for a disenfranchised class because I had a Messianic complex, and every minority group in San Francisco had a lawyer including the dykes. The flower children were starting then, and nobody would take them because they were dirty and they stunk and they were getting busted for dope. I didn’t give a damn whether dope was legal or not, only that these kids were not being treated equally in the eyes of the law. Then bails were incredibly high, they were treated rudely and were given stiff sentences for first offenses. One time it was the joint for a joint. A previously convicted armed robber got out on $7500 bail while a kid with no previous record was given $10,000 bail for one marijuana cigarette.

“I also knew that behind every hippie stood a middle-class family – economically the hippies were sound.

“Let me emphasize that we, Michael and I, really loved these people. We flew all over the state, and people called us from all over the county. By 1967 we were representing 200 free cases a year. We knew they are all coming to the Haight in the summer of ’67 and somebody would have to represent them. So Michael and I started HALO – the Haight Ashbury Legal Organization. We put on a benefit at Winterland to finance it – all the big rock bands played because some of them had been my clients for dope busts.

“Stepanian and I represented four hundred kids that summer of ’67 – The Summer of Love. I got everyone bailed out on my signature. In seven years of dope cases I’ve only had two people jump bail. All the rest stayed around to catch the action.

“By the end of ’67 dope was boring me. I felt we had done everything there was to do. I thought music would be fun. It was a challenge to start it in San Francisco. The music kids, the people in the rock bands were being abused by the record companies the same way the hippies were with dope. They were the victims of unfair, dishonest contracts. The record companies didn’t understand the market for their music. Music was the same Messianic trip as dope. I helped the kids and helped begin the music business in San Francisco.”

“My first music show was at the Fillmore in 1967. I rented the hall for $75 on a Thursday night. It turned out to be the ‘Electric Kool Aid Acid’ Test with the Grateful Dead and a garbage can of Kool Aid spiked with LSD. I did it with Ken Kesey. I told Kesey, “I don’t think anyone will come. He said, ‘Just rent the hall, they’ll come.’ Everybody in the place, all these freaks were down on the ground writhing around. A cop came by and I said, “Have you ever seen anything more peaceful?”. The cop said, ‘We usually have trouble with drunks around here’ and walked on.”

Michael Stepanian, Brian’s partner, thirty-one, a flamboyant Armenian, has an incredible energy and an instinct about people which rarely fails him. Strong, burly, tough-talking, an ex-New Yorker with a big heart and a big mouth, he came to San Francisco four years ago with “nothing but a law degree and an ambition to take the town.”

Now he practices law in Victorian splendor in an office replete with crystal chandeliers, Empire settees and a huge chair garnered from the MGM auction, while Brian’s smaller office upstairs is furnished in Naughahide.

Whatever chauffeur Stepanian can con for the week takes him around the city in a black ’55 Packard with turquoise front fenders. Reclining on the plush leather seat, fingering a large bow tie, Stepanian resembles nothing so much as his current idol, Don Corleone.

“My clients are my friends,” says Michael. “We have some of the same skills, attitudes, anxieties and insecurities. If you’re going to be a criminal trial lawyer, why not have people as your clients you’d like to have dinner with.”

Both the fighter instinct and the show biz comes out in Michael’s courtroom performances which have livened numerous judges’ otherwise routine mornings. “Your honor, why don’t you guys legalize grass so you can get to work on the heavy stuff. If you’d read The Godfather you’d know what I mean.”

Referring to his three principal areas of action – the courtroom, the rugby field or girls – he says, “If the truth be known, you gotta have moves. Moves, man, that’s the thing.”

Another pair of dope lawyers, Michael Metzger and Daniel Weinstein, first faced each other as prosecutor and defense attorney in a Federal courtroom a year and a half ago in the trial of Frank Werber, former manager of the Kingston Trio and now owner of the Trident Restaurant. Werber was accused of conspiracy to smuggle a large amount of marijuana into the United States, and the possession and dealing of marijuana. After a well-publicized trial on the dealing charges, he was acquitted. (Attorney Terence Hallinan presented a “religious defense” – that smoking dope could be a religious experience and arrest for possession would be a violation of the First Amendment, but to no avail – Werber was convicted on that charge, fined 2000 dollars and sentenced to six months in jail.)

Shortly after the Werber trial Metzger and Weinstein went into partnership and are now two of the most successful dope lawyers in the city. In addition to dope, they do selective service cases, represent the rock group, “The Grateful Dead,” and a number of hip businesses.

Metzger, 33, began as an extremely skillful rackets fighting DA in New York City. A certificate naming him to the “Honor Legion of the Police Department of The City of New York” hangs on his office wall. He spent his time prosecuting Mafia types and big Wall Street racketeers, the kind of thing that got his picture on the front page of the New York Times. It was, he said, “a rarified atmosphere.”

Then one hot day while caught in midtown traffic he decided he couldn’t take New York anymore. He came to San Francisco as a United States attorney and began prosecuting “ordinary people” for the first time. It was a revelation. In the middle of one trial he was prosecuting a conscientious objector, and became convinced of the sincerity of the CO, so he asked the judge to throw the case out of court. Shortly afterwards, he quit. “I didn’t want to be involved in the prosecution of people who were basically decent people accused of criminal behavior.

Before the Werber trial, Metzger almost never had a dope case. Now he and Weinstein represent Owsley Stanley, the “LSD king,” (“I didn’t even know what acid was”) and Ken Connell, one of the five arrested in Greece for the smuggling of a ton and a half of hash.

Having worked “on the side of the law” for so many years, Metzger is particularly aware of the psychology of the police: “Whenever you get into vice enforcement like gambling, prostitution and narcotics which are victimless crimes, it can easily lead to police corruption. But not with dope. There is no bribery involved with dope. The cops wouldn’t trust a dealer. They know these guys are likely to get out of it. A cop can trust a regular criminal, a gambler, a pimp. But a cop knows a guy who’s dealing can go get his PhD in Poly Sci and become the police chief someday. . .”

Weinstein, twenty-nine, might be called a nice Jewish boy. The son of a rabbi, he graduated from Harvard Law cum laude, practicing first as a public defender. He has a lot of dope cases, including clients who told him, “I don’t want you anymore. I’m getting a real lawyer.”

He quit the public defender’s office and was all set to take an OEO funded law research job at Berkeley when Frank Werber called him and asked him to take his case. He won, got a lot of publicity and was on his way.

He’s had three major cases in Greece involving the smuggling of hashish, including the one with the Playboy Playmate of the month, Gloria Root. He has defended big smugglers as well as conscientious objectors, but when asked which side of the generation gap he’s on Weinstein hesitates, staring at the tropical fish in his office.

It’s a real problem to know where you are, to know how to square both worlds. You don’t want to dress up and do a hippie do and don’t want just the straight world. You want a sense of discipline, of purpose, make a contribution to the age. I think about teaching a lot or going to live in the country. I don’t want to do this kind of law too long, it takes too much out of your guts. It’s difficult to strike a balance.”

There are no tropical fish or crystal chandeliers in pony-tailed Richard Cohen’s dilapidated Sausalito office. Instead, an old couch is pushed against one wall, the springs and stuffing hanging out. On another wall is a plywood shelf full of scraps of paper, a little hot plate with a pressure cooker and a package of natural brown sugar. A vegetarian who lives communally, Richard, twenty-nine, talks in the soft drawl of his native West Virginia.

“The most I’ve charged for a complicated case was $300. I try to get enough bread to pay the bills. I do not accumulate wealth. There is no professionalism in my practice of law. The people I’m helping are my brothers. Just because I have a degree doesn’t mean I’m better than anyone. Being a lawyer is a dying profession, at least the eliteness that goes along with it. The law is basically a big logic trip. The judge is on a power trip. He’ll rip you off whenever he wants, but don’t give it any energy. It’s a matter of understanding whether the law conforms to any sort of reality or not. The criminal is just used as a means of society to let off steam. People project all their paranoia onto that cat. There is no need for law right now. I hope there will not be a need in my lifetime. If you have respect for your fellow man you don’t harm him. Leary, for example, is a righteous dude, but he put himself into the position of a leader, and when you do that you set yourself up for a fall.”

Was it more difficult to help his people because of his hippie appearance and views? He shook his pony-tail, “No, I try to be honest, to get along in court, I can fit my head into their gears without it bringing me down. I just talk to people. I felt freaky last year in the legal trip, but the new lawyers this year are different. There’s more freaks now.”

Tony Serra, thirty-three, also lives communally. He doesn’t have a bank account, owns no assets or property, does over fifty percent of his legal work free. He identifies strongly with the values of the hip subculture of communal living, sharing, love, non-violence and brotherhood, and hopes for the day when legalized hallucinogenics “will be a vehicle toward societal self-realization.”

Tall, dark, intense as he talks, the words flow out of Serra: “The human species is beautiful. There’s no we or they. We’re one bouquet of flowers. It’s all perfume. I grew up in the fifties. I was All-City Football. Then I went to Stanford and played football, baseball, boxed and studied philosophy. Later at Stanford Law, I was on Law Review.

“I was conditioned for war, competition and aggression. In the fifties at Stanford, I played football and drank. In the sixties it was hallucinogens. Now I can relate spiritually on the same dimensions as those who find themselves with cannabis. I’m a hybrid of both cultures, but since I’m older I retain the warrior instinct conditioned into people my age. I consider myself a semantic warrior doing battle in the courts. Hopefully younger people won’t have to function that way. I don’t believe in the concept of criminality. People work through fantasies on their own level. Some express their fantasies violently. My people are peaceful people. They are not participating in activities which lead to war and human suffering. Each of my cases is its own flower, a valuable blossom as is each day, minute, thought. In a large number of senses it is only fortuitous that I’m an attorney.”

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments