Original Publication: Newsweek, March 10, 1975

Almost everyone is curious about China, but few will have a better opportunity to experience it than those who see THE OTHER HALF OF THE SKY: A CHINA MEMOIR. In 1973 Shirley MacLaine visited China with a delegation of seven disparate American women and a four-woman film crew. This filmed record of what they saw is an intensely moving leap forward into a society whose values are so different from our own that China emerges as both fascinating and frightening.

The film, a collaborative effort by MacLaine and the award-winning 28-year-old filmmaker Claudia Weill, begins by introducing the American women: a rock-ribbed Republican, a Navajo Indian, a Puerto Rican sociologist, a black Mississippi civil-rights worker, a 12-year-old minister’s daughter, a California sexologist and a Texas clerical worker who supports George Wallace. They are by no means a feminist collective, but they are concerned with the roles of women in Chinese society, roles which have changed more radically than in any culture in history. This documentary, which will open first at the Whitney Museum in New York, resembles the usual travelog about as much as Peking duck resembles hamburger.

From the first eerie moment when two of the women find themselves surrounded by a silent, curious crowd on a busy Canton street, the film conveys the mysterious feel of a totally alien culture. The Americans are eager to reach out on a human level that transcends politics, but they soon learn that nothing is separate from politics in China. Young women tell them the first quality they seek in a mate is a high political consciousness. The Americans visit classrooms, day-care centers and collective farms where everyone is happily laboring for Chairman Mao. When one American joins in a tug of war so her side can win, the children are bewildered and the teacher stops the game. “Friendship first,” she says, “competition second.”

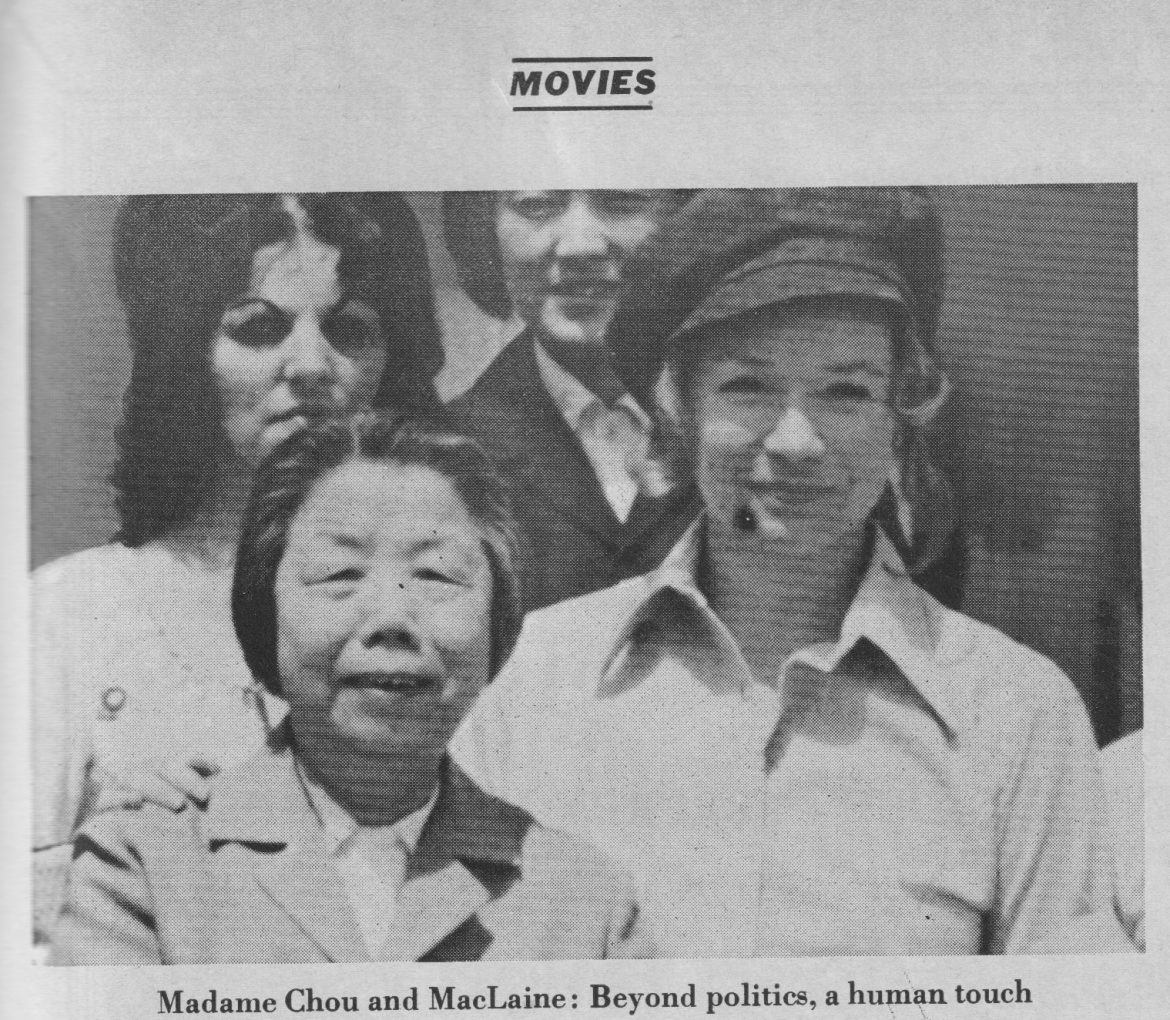

Spontaneous: The Americans were apparently allowed to go where they wished (with the odd exception of a film studio), and some of the best moments in the film, which is beautifully photographed by Weill, seem utterly spontaneous. We see a woman undergoing a Caesarean birth while anesthetized by acupuncture. A moment later, she’s munching an apple and waving to the observers. A farm boy tells the American group he wants to grow up to fight the American “imperialists.” The dignified Madame Chou En-lai, in response to a question by MacLaine, patiently explains there’s no room in China for individual artistic genius. “Politics,” she says, “is reflected in the form of art.”

Some of the group are put off by these sentiments, some find them appealing. What comes through most strongly in the film, however, is a powerful sense of human contact between the Chinese and the Americans. Unita Blackwell of Mississippi is moved to tears at an exhibit of children’s drawings. A little Chinese girl silently leads her to a picture of a black woman holding a Chinese baby. Even Pat Branson, the Wallaceite, is shaken by the experience, exclaiming: “I want to know why these people are so happy.” “The Other Half of the Sky” will disturb some who cling to preconceived ideas about China. And the film can be seen as an absorbing portrait of a society totally programed for collective bliss. But it is a testament to both the American women and the Chinese people that wo groups of strangers could overcome their tremendous cultural barriers and make such warm contact with each other as human beings.

This article is typed from the original material. Please excuse any errors that have escaped final proofreading.

No Comments