Original Publication: New York Times Magazine, Spring 2002

“Artem,” I said to my young interpreter in the Tajik city of Dushanbe on a day of particularly fierce “Tajik Torture” – the catchall phrase we journalists used to describe the botched communications, contaminated food and oppressive bureaucracy we all dealt with. “I’m going to teach you a new cliche: When the going gets tough, the tough go shopping. Take me to the market!”

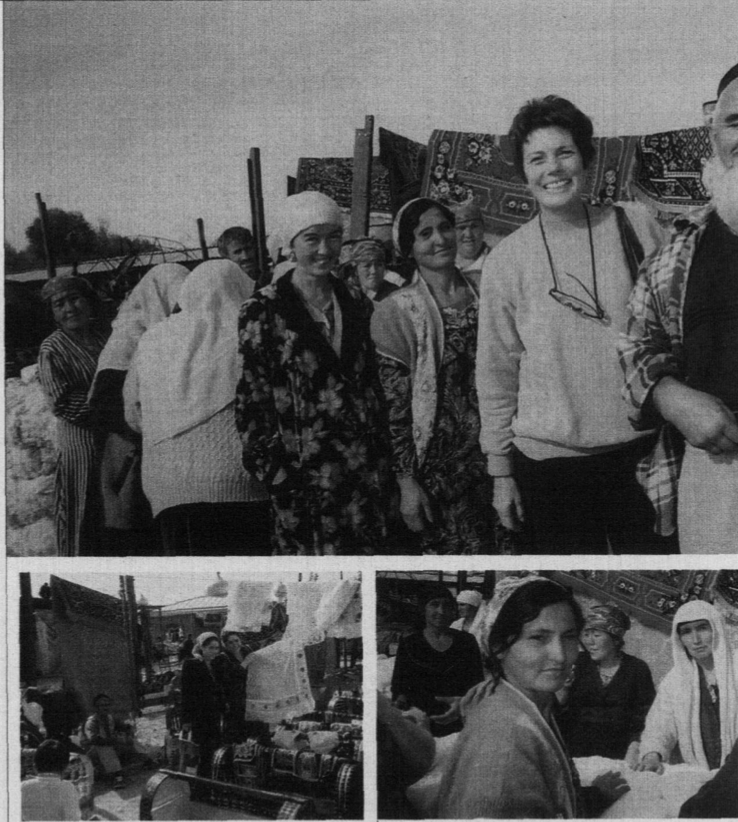

So it was on a recent war-related assignment to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan for Vanity Fair that I chose not to repair to the bar, where the weary correspondent traditionally takes his release, but opted for the bazaar instead.

There for a glorious hour between interviews, I escaped into a world right out of Indiana Jones: mazes of gauzy, white clothcovered stalls and passageways spewing out in all directions across muddy fields. Up one aisle would be the pots and pans; in another, hand-carved cradles with inlaid mother-of-pearl; vibrant-colored spices in burlap bags; wedding finery in gold lame; tasseled slides out of the Arabian Nights; delicate red teapots for $5; soft, handknitted angora socks for $1; and similarly priced treasures – like the flour sifter constructed from the donated “U.S.A.” food tin that I simply had to have. Rarely did anything cost more than $20. Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries of the former Soviet Union, and $20 is considered a generous monthly salary.

“No, I will not bargain with you – you are a foreigner!” the young man selling the angora socks said to me. For years under communism, most “foreigners” were considered spies; but if I did not bargain in this trader’s land, I would be considered worse than a spy, a dupe. So I’d laughingly haggle a bit until my interpreter, Artem Pashenko, would say, “If you go any lower, he will be offended.”

Taking offense was a great seller’s tool. One day, when I had to wait several hours and jump through yet another bureaucratic hoop trying to interview a Russian general stationed there, I discovered a dingy from the general’s headquarters. Inside the shop, I was told the electricity had failed, making it so dark that I could barely see the old tent hangings, flamboyantly embroidered in silk- and had to carry them to the front door.

“I told him you were a Western collector, an expert with great knowledge,” Artem whispered.

“Why?” I asked.

“So he will show you his good things and not cheat you.”

I spied an antique dagger in a twisted ram’s-horn case for $35; I offered $20. The shopkeeper immediately took it from the counter and put it back on the shelf. “He is offended,” Artem said.

When the owner carefully unfolded the most expensive thing in the shop for me – a beautifully worked silk hanging that would have made an exquisite canopy or king-size bed cover, he said its price was $350 in a way that implied that the sum was far beyond all of our means. Indeed, in that setting it would have been unseemly to have that kind of money to spend, so I murmured, “How lovely,” and let it go. By the time he added up my selection of several large hangings, two colorful vintage tunics that would make great presents for friends, and the dagger for my son, the total was $117; he had even closed the shop to attend exclusively to the high-roller from the West. I started fumbling around in the dark, digging in my purse, trying to find the money. Suddenly, miraculously, the shop was bathed in light – the shopkeeper’s assistant had thrown a switch in the back office. Obviously, when it came time to count the money, the lights went on.

“How are you going to get all that stuff home?” people would ask when I told them I was doing my Christmas shopping in the war zone. By now I knew enough to take along a big duffel bag folded into my travel bag, and I had already taken it out and begun to fill it even before I arrived in Tajikistan. In Uzbekistan, for example, I had found elegant handdyed ikat silks that cost $1 to $2 a yard – here, they would cost 10 times that if you could ever find them. Of course, having all that silk and those wall hangings, I realized that I could stuff some wonderful hand-painted plates ($3.50) between the layers with no fear of breakage. An old coral choker decorated with ancient coins from the Silk Road was my last buy – I could not resist it at $30.

My most important purchase, however, took up almost no space, and I found it not at the bazaar but in a pharmacy near one of the outdoor food markets. When I first arrived in Dushanbe, a Russian friend admonished me that merely washing my hands with soap before eating was not a sufficient precaution, because of the polluted water. He squirted some clear liquid from a small plastic bottle on my hands and wrists.

“What is that?” I asked.

“It comes from Moscow,” he said conspiratorially.

The next day, after Artem and I had found the very same bottle in the local pharmacy, I proudly pulled it out of my bag when I dined with my Russian friend again.

“Where did you get that?” he demanded.

“At the pharmacy.”

“Do you know what the label says?”

“No, what?”

” `To be used after unsafe sex.”‘ My initial shock was instantly tempered by the thought that a little embarrassment should never get in the way of finding a bargain.

No Comments